Moby Dick, Myth, and Classical Moralism: Bulkington as Hercules

advertisement

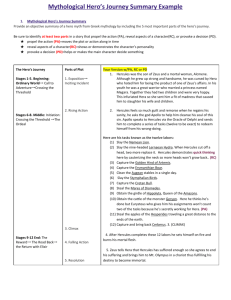

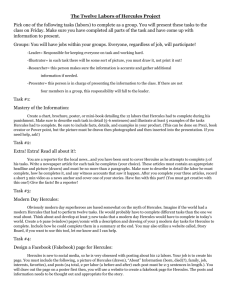

Moby Dick, Myth, and Classical Moralism: Bulkington as Hercules Jonathan Cook, Leviathan 5.1 (2003): 15+ Readers of Moby-Dick have long been fascinated by the figure of Bulkington, who makes an exemplary appearance early in the novel and then mysteriously vanishes from the narrative. First introduced in "The Spouter Inn" (Ch. 3), Bulkington subsequently appears at the helm of the Pequod in "The Lee Shore" (Ch. 23), where he serves as the inspiration for Ishmael's well-known disquisition on the choice between sea- and land-based values. Bulkington accordingly impresses Ishmael in "The Spouter Inn" as an extraordinary physical specimen; whereas in "The Lee Shore" his reappearance inspires the narrator with rhapsodic praise of Bulkington's moral fiber as a man preferring the open sea over the port, hardship over comfort, solitude over society, and intellectual freedom over dogma. Students of the novel's composition have wondered whether Bulkington was meant to play a larger role in the narrative, despite Ishmael's initial disclaimer that Bulkington was "but a sleeping-partner" shipmate, and his later verbal cenotaph of the heroic sailor's life and death in "The Lee Shore" ("this six-inch chapter is the stoneless grave of Bulkington"). Harrison Hayford, for example, interprets Bulkington as an "unnecessary duplicate" originally intended for the major role of Ishmael's companion that Queequeg later assumed, but kept as a vestigial presence after final revision of the novel. (1) Other critics have sought an underlying thematic meaning in Bulkington's appearance, or adduced his significance from an assumed biographical model. Thus half a century ago, Melville's first important myth critic, Richard Chase, postulated that Bulkington was the novel's "true" Promethean and democratic hero, who nevertheless had to disappear from the narrative because if he remained he would have been compelled to resist the despotic command of Ahab, the novel's "false" Prometheus. In the late sixties, S.A. Cowan argued that Bulkington represented the virtues of Emersonian self-reliance in the quest for truth, and the preference for philosophical realities over social conventions that forms part of an intellectual tradition going back to Plato. More recently, Robert K. Wallace asserted that the figure of Bulkington embodied Melville's admiration for the painter J.M.W. Turner, whose work allegedly influenced the writing of Moby-Dick. (2) Although occasionally suggestive, none of these potential sources for the character of Bulkington has proved to be fully convincing. Quite possibly, another implicit model for this mysterious Southern seaman exists, one that combines the mythological, philosophical, and iconographic levels of significance that the critics cited above have imputed to this character. Keeping in mind that Bulkington is ultimately invoked as a "demigod" and given a parting "apotheosis," I would like to suggest that the figure of Bulkington is a modern embodiment of the semi-divine Greek hero Hercules (Herakles), and his appearance in "The Lee Shore" draws on a famous moral topos associated with Hercules's life, the "Choice of Hercules" between Pleasure (or Vice) and Virtue, as well as the example of the hero's agonizing death through self-immolation and subsequent apotheosis. These mythic associations, in turn, may enhance our understanding of Bulkington's role in the novel and resolve some of the mystery arising out of his emblematic appearance. A wide range of mythic lore surrounds the life of Hercules, the classical Greek hero par excellence, and has provided the subject matter for a substantial amount of literature and art from classical times to the present. (3) Among the many allusions to his life in classical literature, Hercules was the subject of surviving dramas by Sophocles (The Women of Trachis), Euripides (Herakles) and Seneca (Hercules Furens, Hercules Oetaeus). In classical art and sculpture, Hercules was most often represented with a lion-skin cloak, club or bow. (On his trip through Naples in February 1857, Melville would observe the well-known Farnese Hercules, a full-length statue featuring the brawny hero leaning on his club.) (4) Originally known as an embodiment of physical strength and courage, Hercules was eventually given a complementary identity as a representative of moral fortitude, an identity influential in both classical and modern Western culture. In keeping with the latter tradition, the Victorian art critic John Ruskin asserted in a mythological treatise that Hercules was "the perpetual type and mirror of heroism, and its present and living aid against every ravenous form of human trial and pain." (5) According to Greek myth, Hercules was the son of Zeus and Alcmene, the mortal wife of Amphitryon, and was early endowed with a god-like strength that included superior skills in archery and wrestling; but he was also afflicted with a violent temper and subject to fits of madness due to persecution from a jealous Hera. (6) Hercules is perhaps best known for the Twelve Labors he performed for King Eurystheus of Argos, during which he vanquished a number of terrible beasts and accomplished several superhuman tasks throughout the Peloponnese and greater Mediterranean world: strangling the Nemean lion, destroying the nine-headed Lernean hydra, capturing the goldenhorned Cerynthian hind, overcoming the Eurymanthian boar, cleaning the filthy stables of King Augeus of Elis, driving off the noisome Stymphalian birds in Arcadia, capturing the Cretan bull, harnessing the man-eating mares of Diomedes in Thrace, procuring the girdle of the Amazon queen Hippolyta on the Black Sea, obtaining the cattle of the three-bodied Geryon on the island of Erytheia off the coast of Spain, procuring (with the help of Atlas) the golden apples of the Hesperides in the far west, and collaring (with the help of Athena and Hermes) the three-headed dog Cerberus in the underworld. Along with these tasks Hercules had time to overcome the giant Anteus, set up the Pillars of Hercules, establish the Olympic Games, sail with Jason and the Argonauts, fight the centaurs, conquered Troy, liberate Prometheus, and rescue Alcestis from Hades. In his domestic life, Hercules married several times and was accidentally killed by his last wife Dejaneira, who inadvertently gave him a poisoned shirt to wear (the Shirt of Nessus), thinking it was a love charm. Realizing that his death was foredoomed, Hercules built a funeral pyre for himself on Mount Oeta in Trachis. As his body was being consumed on the pyre, his father Zeus sent a thunderbolt to extinguish the flames and announced that the hero's immortal half would ascend in a chariot to Olympus, where he would be made the twelfth Olympian god and, once reconciled to Hera, married to the young Hebe. Hesiod noted of Hercules' apotheosis in the Theogony: "Happy he! For he has finished his great work and lives amongst the undying gods, untroubled and unaging all his days" (Loeb Edition, 11. 951-53). The episode in Hercules' life that made him an influential symbol of moral fortitude was the famous "Choice of Hercules" between Vice and Virtue first set forth as parable by the sophist Prodicus (a teacher of Socrates) in Xenophon's Memorabilia (ii, 1, 21 ff.), elaborating on a motif found in Hesiod's Works and Days (11. 286-92). In Xenophon's account, the youthful Hercules, on his way to tend his father's cattle on Mount Cithaeron, was met at a crossroads by two women representing Pleasure (Hedone) and Virtue (Arete); the former urged Hercules to take the path into a pleasant glade, the latter the path up a steep hill. After listening to the arguments of the two figures, Hercules chooses the steep path recommended by Virtue, with its sacrifices and hardships but eventual assurance of renown. The following is a sample of the opposing benefits that Pleasure and Virtue present to the impressionable young hero: "First [said Pleasure], you will worry neither about war nor about business. Instead, you will roam about examining what delightful food or drink you might find, and what delight you might see or hear, what pleasant things you might smell or touch, which favorites would especially delight you in associating with them, and how you might sleep most comfortably, and how you might obtain all these things with the least trouble." At this point the other woman [i.e., Virtue] approached and said, "I too have come to you, Herakles, since I knew those who begot you and that nature of yours, having observed it in your education. Therefore, I have hope: for you, that if you should take the road toward me, you will become an exceedingly good worker of what is noble and august; and, for me, that I will appear still far more honored and more distinguished for good things. I shall not deceive you with preludes about pleasure. But I shall fruitfully describe the disposition the gods have made of the things that are." (7) Following its use as a moral topos in the classical world (as, for example, in Cicero's De Officis), the "Choice of Hercules" outlined above was revived by early humanists beginning with Petrarch in his De Vita Solitaria. The theme of Hercules choosing Virtue over Vice eventually became a particular favorite for many Renaissance writers and artists, and continued to be a neoclassical commonplace in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as well. Painters who produced works in the tradition included Durer, Cranach, Veronese, Annibale Carracci, Rubens, Poussin, and Benjamin West. (At the end of this life, Melville himself owned a print of Hercule Entre le Vice et la Virtue by the seventeenth-century Flemish artist Gerard de Lairesse. See fig. 1.) Literary, theatrical, and musical adaptations of the theme included Ben Jonson's masque Pleasure Reconciled to Virtue; Steele's Tatler essay no. 97; Shenstone's masque The Judgment of Hercules; Lowth's poem "The Judgment of Hercules"; Handel's oratorio The Choice of Hercules; Metastasio's libretto Hercules at the Crossroads, and Wieland's drama The Choice of Hercules (a). (8) [FIGURE 1 OMITTED] Evidence of the popularity of the Choice of Hercules in the classically conscious new American nation can be seen in the fact that in 1776, John Adams suggested it as the image to be depicted on the Great Seal of the United States, in keeping with the current belief that a republic must be upheld by the virtue of its citizens. As an inspirational message in education, the theme was a familiar topos within the classical curriculum that served many American schools and colleges throughout the nineteenth century. So, for example, it was adapted by a Princeton literary society, the American Whigs, who in 1819 commissioned the well-known Philadelphia portraitist Thomas Sully to paint a version of the scene that was subsequently engraved for use on the society's diplomas. Melville doubtless encountered the Choice of Hercules, along with other classical lore, during his student days in the 1830's at the Albany Academy and the Albany Classical School, or as a member of the Ciceronian and Philo Logos societies, whose heavily moralistic debates led to Melville's first appearance in print in the Albany Microscope in 1838. The classically educated Margaret Fuller set forth the general significance of this well-known moral topos in an 1845 review of Thomas Carlyle's edition of Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches: "The temptations in the wilderness, choices of Hercules, and the like, in succinct or loose form, are appointed for every man that will assert a soul in himself and be a man." (9) With Hercules' mythical career in mind, Bulkington in Moby-Dick may be seen as an exemplar of the classical hero's physical prowess and moral fortitude. Significantly, Bulkington's name associates him with both supreme muscular strength (bull) and an elevated character (king), the two most outstanding traits of the Greek hero in the main classical tradition. (10) Bulkington's first appearance in the novel, as a member of the returning Grampus's crew at the Spouter Inn, is notable for its depiction of an elevated moral nature united to a remarkable muscular form that features "noble shoulders" and a "chest like a coffer-dam" (i.e., the watertight compartment used in the construction of a bridge or pier): I observed, however, that one of them held somewhat aloof, and though he seemed desirous not to spoil the hilarity of his shipmates by his own sober face, yet upon the whole he refrained from making as much noise as the rest. The man interested me at once; and since the sea-gods had ordained that he should soon become my ship-mate (though but a sleeping partner one, so far as this narrative is concerned), I will here venture upon a little description of him. He stood full six feet in height, with noble shoulders and a chest like a cofferdam. I have seldom seen such brawn in a man. His face was deeply brown and burnt, making his white teeth dazzling by the contrast; while in the deep shadows of his eyes floated some reminiscences that did not give him much joy. His voice at once announced him to be a Southerner, and from his fine stature I thought he must be one of those tall mountaineers from the Alleganian Ridge in Virginia. When the revelry of his companions had mounted to its height, this man slipped away unobserved, and I saw no more of him till he became my comrade on the sea. (NN MD, 16) While he is given a tentative geographical origin in western Virginia, the bronzed and brawny figure here may also evoke the demigod Hercules, an association enhanced by Ishmael's allusion to the "sea-gods" who allegedly arranged his voyage. (Bulkington, in fact, has a mythical analogue in the Hercules who sailed with the Argonauts in quest of the Golden Fleece.) By the same token, Bulkington shuns the bibulous "revelry" of his comrades, in accordance with the figure of the moralized Hercules, while the hint of a mysterious sorrow in his eyes may recall that aspect of Hercules' life associated with his occasional bouts of madness, which at one point caused him to murder his children by his first wife, Megara of Thebes (the subject of Euripides's Herakles and Seneca's Hercules Furens, and in most accounts the immediate reason for his undertaking his Twelve Labors in penance). It should be noted that in Chapter 86 of Moby-Dick ("The Tail"), in a discussion of the combined power and beauty of the whale's flukes, Ishmael evokes the beauty of Hercules' statuesque form (probably with the Farnese Hercules in mind) in a manner that also may reflect back on Bulkington's representation as a paragon of physical and moral strength: "Real strength never impairs beauty or harmony, but it often bestows it; and in everything imposingly beautiful, strength has much to do with the magic. Take away the tied tendons that all over seem bursting from the marble in the carved Hercules, and its charm would be gone" (376). While Bulkington's brief appearance at the Spouter Inn suggests that he may be a modern type of the classical hero, his unexpected reappearance at the helm of the Pequod in "The Lee Shore" (Ch.23) adds another dimension to the portrait. As noted, this chapter postulates an emblematic contrast between the values of the sea and the land, as suggested by Bulkington's immediate shipping out on the Pequod after his recent return from a lengthy voyage on the Grampus. And it is here that the well-known moral dimension of the Hercules myth may serve as an implicit prototype, for Melville appears to have adapted the "Choice of Hercules" between Pleasure and Virtue to this chapter's paradigmatic opposition of sea and land, while subversively rewriting the conventionalized, quasiChristian message of the hero's sacrificial choice. In "The Lee Shore," Bulkington successfully resists the creature comforts of the port, which paradoxically represent a deadly threat to the mariner trying to land in stormy weather. The passage relies on an epic simile comparing Bulkington to the homeward-bound ship, the latter standing for the heroic sailor's "soul," in the manner of Platonic allegory, as the comparison later makes clear: Let me say that it fared with him [Bulkington] as with the stormtossed ship, that miserably drives along the leeward land. The port would fain give succor; the port is pitiful; in the port is safety, comfort, hearthstone, supper, warm blankets, friends, all that's kind to our mortalities. But in that gale, the port, the land, is that ship's direst jeopardy; she must fly all hospitality; one touch of land, though it but graze the keel, would make her shudder through and through. With all her might she crowds all sail off shore; in so doing, fights 'gainst the very winds that fain would blow her homeward; seeks all the lashed sea's landlessness again; for refuge's sake forlornly rushing into peril; her only friend her bitterest foe! (NN MD, 106) Just as the figure of Pleasure promises the young Hercules the free indulgence of his physical nature (not the least, a comfortable bed), so the "port" here offers supreme physical comfort, including "warm blankets" and "all that's kind to our mortalities." But to reach the port may involve self-destruction on the lee shore, just as the full indulgence of Pleasure's mandates may eventually bring about physical as well as moral disintegration (the "one touch of land" that will make the ship "shudder through and through"). Ishmael goes on to extrapolate a further moral lesson from this nautical paradigm, claiming that Bulkington's choice of the open sea symbolizes the freedom of the "soul" to shun all conventional wisdom and inherited beliefs, even if this leads to an "ocean-perishing"; for it is better to perish at sea in the lonely pursuit of truth than to die while seeking the mundane comforts of the "slavish shore": Know ye, now, Bulkington? Glimpses do ye seem to see of that mortally intolerable truth; that all deep, earnest thinking is but the intrepid effort of the soul to keep the open independence of her sea; while the wildest winds of heaven and earth conspire to cast her on the treacherous, slavish shore? But as in landlessness alone resides the highest truth, shoreless, indefinite as God--so, better is it to perish in that howling infinite, than be ingloriously dashed upon the lee, even if that were safety! For worm-like, then, oh! who would craven crawl to land! Terrors of the terrible! Is all this agony so vain? Take heart, take heart, O Bulkington! Bear thee grimly, demigod! Up from the spray of thy ocean-perishing--straight up, leaps thy apotheosis! (NN MD, 107) While there is no overt suggestion here of the traditional iconography of the Choice of Hercules, with its "high" road to virtue and "low" road to pleasure, we may nevertheless note that the existential choice presented in this chapter of Moby-Dick posits the attainment of the "highest truth" in the realm of the sea, as opposed to the vile abasement required in the realm of the "slavish shore." The quasi-Shakespearean and Byronic language of this passage may remind us of a comparable assertion of intellectual and creative freedom by Taji, the narrator of Mardi; in fact, such an assertion of spiritual autonomy for the artist is a recurring topos of literary Romanticism. (11) While in the latter stages of Moby-Dick's composition, Melville himself used similar language in a letter to Hawthorne, imputing to his Berkshire friend a rebellious message of "NO! in thunder." (12) But the actual moral paradigm described in "The Lee Shore" is still suggestively patterned after the lore of Hercules, particularly the ascription of the term "demigod" to Bulkington, as well as the latter's final apotheosis, a seemingly direct borrowing from the legend of the Greek hero's divine apotheosis from his funeral pyre at Zeus's command. The reference to an unspecified "agony" in the passage cited above also conveys a distinctly Herculean suggestion in connection with the Greek hero's agonizing death (poisoned shirt and searing flames), the subject of a host of literary, artistic, and theatrical adaptations, as was Hercules' ensuing apotheosis. (13) We know from the novel's conclusion that Bulkington will perish with the rest of the crew of the Pequod, but he will nevertheless arise from the wreck in spirit, according to Ishmael's confident projection, because of the nobility of his choice of sea- over land-based values. And whereas Hercules is rewarded by his father Zeus with immortality for his heroic life, Bulkington is given a symbolic deification for his stoical championship of intellectual and moral freedom. Significantly, the stark contrast between the lonely but noble independence of the open sea and the deceptive appeal of the "slavish shore" suggests that moral fortitude, acceptance of adversity, and studied emotional detachment typical of Roman Stoicism. Melville read Seneca in the late 1840's during the composition of Mardi, and at some point--possibly at this time of wide philosophical reading--he also read Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, all of them leading representatives of Roman Stoicism. In this and other related classical literature, the moralized Hercules was regularly represented as a model stoic hero. (14) In the first chapter of Moby-Dick ("Loomings"), Ishmael had noted of his decision to go to sea as a common sailor: "The transition is a keen one, I assure you, from a schoolmaster to a sailor, and requires a strong decoction of Seneca and the Stoics to enable you to grin and bear it. But even this wears off in time" (NN MD, 6). Beyond this association with the lore of Hercules are there any other literary sources or influences at work in the representation of Bulkington? We should not overlook the fact that Emerson in his essay on "Intellect" (from Essays: First Series [1841]) had presented a moral paradigm nearly identical to that figured by Bulkington in "The Lee Shore," as Merton Sealts first pointed out in his concise overview of Melville's encounter with Emerson's thought, (15) In the following passage, Emerson sets forth the high demands made on the "scholar" or thinker who chooses to pursue "truth" rather than "repose": Exactly parallel is the whole rule of intellectual duty, to the rule of moral duty. A self-denial, no less austere than the saint's, is demanded of the scholar. He must worship truth, and forgo all things for that, and choose defeat and pain, so that his treasure in thought is thereby augmented. God offers to every mind its choice between truth and repose. Take which you please,--you can never have both. Between these, as a pendulum, man oscillates. He in whom the love of repose predominates, will accept the first creed, the first philosophy; the first political party he meets,--most likely, his father's. He gets rest, commodity; and reputation; but he shuts the door of truth. He in whom the love of truth predominates, will keep himself aloof from all moorings and afloat. He will abstain from dogmatism, and recognize all the negatives between which, as walls, his being is swung. He submits to the inconvenience of suspense and imperfect opinion, but he is a candidate for truth, as the other is not, and respects the highest law of his being. (16) For Emerson's antithesis between "truth" and "repose," we may compare Melville's antithesis between the symbolic associations of sea and shore. Both authors emphasize the high cost in suffering and uncertainty that an individual must bear for preferring the demands of truth to the ease of convention; but such drawbacks are compensated by the exalted reward that comes from such a preference (obeying the "highest law" of one's being for Emerson; "apotheosis" for Melville). Given his receptivity to some aspect of Emerson's thought in the late 1840's, as Sealts has noted, it would seem highly likely that the argument of "Intellect" carried over into "The Lee Shore," supplemented by the imagery of moral fortitude and stoical self-renunciation found in Hercules' mythological and philosophical career. It is also relevant to note here that the figure of Hercules is later alluded to in Moby-Dick in connection with "The Honor and Glory of Whaling" (Ch.82), a humorous disquisition in which Ishmael seeks to find exalted mythological ancestors (e.g., Perseus, St. George, Vishnoo) for the modern whaleman. Considering whether to induct Hercules into this select society, Ishmael notes the legend that the classical hero was once swallowed by a whale: Whether to admit Hercules among us or not, concerning this I long remained dubious: for though according to the Greek mythologies, that antique Crockett and Kit Carson--that brawny doer of rejoicing good deeds, was swallowed down and thrown up by a whale; still, whether that strictly makes a whaleman of him, that might be mooted. It nowhere appears that he ever actually harpooned this fish, unless, indeed, from the inside. Nevertheless, he may be deemed a sort of involuntary whaleman; at any rate the whale caught him, if he did not the whale. I claim him for one of our clan. (363) The passage shows Ishmael in the role of quixotic comparative mythologist a la Sir Thomas Browne and Pierre Bayle, elaborating on the relatively obscure myth that Hercules was swallowed by a sea monster sent by Poseidon, which Hercules fought while rescuing Hesione, daughter of King Laomedon of Troy; Ishmael goes on to note the myth's obvious resemblance to the story of Jonah. (17) But Ishmael's disquisition here also demonstrates an assimilation of the classical Hercules to a "frontier" American context ("that antique Crockett and Kit Carson") similar to that which I have argued for in interpreting Bulkington as a Herculean hero. The passage's unabashed identification of the Greek hero as a mythic ancestor of the modern whaleman thus provides a potential comic complement to the tragic Herculean message of "The Lee Shore." The character of Bulkington, then, would appear to represent Melville's version of human heroism based on the well-known model of Hercules--a heroism of both physical and moral strength that prizes independence as the ultimate measure of the soul's well-being. Since this is obviously more of a classical than a Christian ideal, Bulkington may be said to serve as an early model for Ishmael's quest for an empirical system of truth beyond the conventional pieties of Christianity; he is thus Ishmael's alternative to the blasphemous example of Ahab, whom Bulkington resembles in a number of respects. And if Father Mapple's sermon on Jonah acts as an implicit religious benchmark against which to measure Ahab's self-centered rebellion against God, the example of Bulkington provides Ishmael with a positive philosophical ideal that encourages freedom and self-sacrifice in quest of truth, and a stoical acceptance of solitude suitable for Ishmael's condition at the end of the narrative. (18) Bulkington thus embodies what the classicist Karl Galinsky considers the essence of Hercules' multifarious mythical and literary identity, a combination of strength and endurance. The Herculean aspect of Bulkington's character may accordingly join the other mythical models that contribute to the rich matrix of characterization in Moby-Dick, as in Ahab's wellknown Promethean attributes. (19) In Bulkington, Melville's mythic imagination is again apparently at work, merging the human exemplar with the archetypal model to create a powerful icon of physical and moral strength anticipating the classically influenced depiction of Billy Budd late in his career. (1) Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or the Whale, ed. Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, and G. Thomas Tanselle (Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and The Newberry Library, 1988), 16, 106; hereafter cited as NN MD). Harrison Hayford, "Unnecessary Duplicates: A Key to the Writing of Moby-Dick," in Faith Pullin, ed., New Perspectives on Melville (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1978), 128-61. (2) See Richard Chase, Herman Melville: A Critical Study (New York: Macmillan, 1949), 58-59; S.A. Cowan, "In Praise of Self-Reliance: The Role of Bulkington in Moby-Dick," American Literature 38 (1967), 547-56; Robert K. Wallace, "Bulkington, J.M.W Turner, and 'The Lee Shore,'" in Christopher Sten, ed., Savage Eye: Melville and the Visual Arts (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991). See also the discussion in the explanatory notes to Moby-Dick, ed. Luther S. Mansfield and Howard P. Vincent (New York: Hendricks House, 1952), 606-7; the editors here suggest several figures as possible biographical exemplars of Bulkington, but consider the recently deceased Virginian, Edgar Allan Poe, as perhaps the most likely (but not conclusive) model. (3) On the rich and complex history of Hercules as a literary, philosophical and artistic subject, see G. Karl Galinsky, The Herakles Theme: The Adaptations of the Hero in Literature from Homer to the Twentieth Century (Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1972). See also Jane Davidson Reid, ed., The Oxford Guide to Classical Mythology in the Arts, 2 vols. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 1:515-60. For an excellent study of the Use of classical myth by American Renaissance writers, see Robert D. Richardson, Myth and Literature in the American Renaissance (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978). (4) See Herman Melville, Journals, ed. Howard Horsford, Lynn Horth, Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, and G. Thomas Tanselle (Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and The Newberry Library, 1989), 103, 460. (5) The Queen of the Air: Being a Study of the Greek Myths of Cloud and Storm (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1869), 6. (6) For a detailed overview of Hercules's mythological history, see Robert Graves, The Greek Myths, 2 vols. (New York: Penguin Books, 1960), 2:84-206. (7) Memorabilia, translated and annotated by Amy L. Bonnette (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994), 39-40. For a discussion as Hercules as a philosophical hero in the classical world, see Galinsky, Ch. 5. (8) For a complete list of works of art, literature, drama and music based on the "Choice of Hercules," see Reid, 1:527-30. On Melville's private collection of prints, see Robert K. Wallace, "Melville's Prints and Engravings at the Berkshire Atheneum," Essays in Arts and Sciences 15 (1986), 59-90. Gerard de Lairesse's Hercule Entre le Vice et la Virtue is identified on p. 83. It is not known when Melville acquired the de Lairesse print, but a likely time would be the last decade of his life when he had enough money to purchase such items; see Wallace, 70. Born in Liege, Gerard de Lairesse (1641-1711) was a painter, printmaker, draftsman and theorist who contributed to the gallicizing of later seventeenth-century Dutch art. Sometimes called the Dutch Poussin, he painted allegorical and historical subjects and promoted classicism in the arts. See Lyckle de Vries, Gerard de Lairesse: An Artist Between Stage and Studio (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1998). (9) On John Adams's suggestion of the Choice of Hercules for the Great Seal, see Meyer Reinhold, Classica Americana: The Greek and Roman Heritage in the United States (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1984), 150, 153-54. On Thomas Sully's depiction of the theme for the American Whigs and its relevance to other student societies, see James McLachlan, "The Choice of Hercules: American Student Societies in the Early 19th Century," in Lawrence Stone, ed., The University in Society, 2 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974), 2:449-94. For an overview of Melville's education in Albany and vicinity in the 1830's, see William H. Gilman, Melville's Early Life and "Redburn" (New York: New York University Press, 1951), Chs. 2 and 3; for Melville's early articles appearing in the Albany Microscope, see 251-63. Margaret Fuller's allusion to the Choice of Hercules is from a New York Tribune review reprinted in Life Without and Life Within; or Reviews, Narratives, Essays and Poems, ed. Arthur B. Fuller (Boston: Roberts Bros., 1890), 190. (10) Compare a notation Emerson made in his journal in 1857: "The ancients to make a god added to the human figure some brutal exaggeration, as the leonine head of Jove, the bull-neck of Hercules; and Michel Angelo added horns to give mysterious strength to the head of Moses" (The Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Vol. XIV, 1854-1861, ed. Susan Sutton Smith and Harrison Hayford [Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978], 194). (11) See Chapter 169, "Sailing On," in which Taji likens his exploration of the "word of mind" of Mardi to Columbus's discovery of the New World: "But this new world here sought is stranger than his; who stretched his vans from Palos. It is the world of mind..." The passage concludes: "So if, after all these fearful, fainting trances, the verdict be, the golden haven is not gained;--yet, in bold quest thereof, better to sink in boundless deeps, than float in vulgar shoals; and give me, ye gods, an utter wreck, if wreck I do" (NN Mardi, 557). For other literary analogues to Ishmael's sea / land dichotomy, see the explanatory notes in Moby-Dick, ed. Mansfield and Vincent, 657. (12) As Melville wrote while imputing his own beliefs to Hawthorne, "There is the grand truth about Nathaniel Hawthorne. He says NO! in thunder; but the Devil himself cannot make him say yes. For all men who say yes, lie; and all men who say no,--why, they are in the happy condition of judicious, unincumbered travellers in Europe; they cross the frontiers into Eternity with nothing but a carpet-bag,--that is to say, the Ego [i.e., the conscious thinking subject]. Whereas those yesgentry, they travel with heaps of baggage, and damn them! they will never get through the Custom House" (NN Correspondence, 186). We may note that Melville's nay-sayers are, like Bulkington, "judicious, unincumbered travellers" who attain to truth through their freedom from any inhibiting sentimental, cultural, or metaphysical "baggage"; the sea/land dichotomy of "The Lee Shore" is thus represented here by two classes of land travelers, those who are loaded down with superfluous luggage, and those who travel light, with only their minds. (13) Over the last two centuries, the death of Hercules has inspired, among others, Samuel EB. Morse's "The Dying Hercules" (a painting), Holderlin's "Dejaneira to Hercules" (a poem), Arnold's "Fragment of a Chorus of a 'Dejaneira" (a poem), Frank Wedekind's Herakles (a drama), Kurt Weill's Royal Palace (a ballet-opera), and T.S. Eliot's "Little Gidding" (in Four Quartets). Representations of Hercules's apotheosis have been most popular among Renaissance and Baroque artists (e.g., Correggio, Veronese, Rubens, and Tiepolo); but the subject has also been treated by the German Romantic writers Holderlin ("On Hercules") and Schiller ("Zeus to Hercules"). For a full list of representations of Hercules's death and apotheosis, see Reid, 544-48. (14) On Hercules as a stoic, see Galinsky, Chs. 6 and 8. On Melville's reading of Seneca, see Merton M. Sealts, Jr., Melville's Reading, rev. and enlarged ed. (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1985), nos. 457 and 458. Melville's familiarity with the writings of Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius is demonstrated by allusions in The Confidence-Man (Chapter 19) and Clarel (Book IV, Canto 20), respectively. (15) See "Melville and Emerson's Rainbow," in Pursuing Melville, 1940-1980: Chapters and Essays (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982), 264-65. In his 1967 article on Bulkington, Cowan does not cite the passage from "Intellect" in relation to the alleged Emersonian aspects of "The Lee Shore." (16) The Collected Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Vol. II, ed. Joseph Slater, Alfred R. Ferguson, and Jean Ferguson Carr (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), 202. (17) Graves notes of Hercules' encounter with the sea monster: "With Athene's help, the Trojans then built Heracles a high wall which served to protect him from the monster as it poked its head out of the sea and advanced across the plain. On reaching the wall, it opened its great jaws and Heracles leaped fully-armed down its throat. He spent three days in the monster's belly; and emerged victorious, although the struggle had cost him every hair on his head" (2:169). This curious incident ultimately derived from a few lines in Book 20 of the Iliad (11. 145-48) and later scholiasts and commentators thereon; see Graves, 2:173. The explanatory notes in Moby-Dick, ed. Mansfield and Vincent, 778-79, point out that much of the mythical lore in this chapter and the following ("Jonah Historically Regarded") was likely drawn from the entry on "Jonas" in Pierre Bayle's Historical and Critical Dictionary, the entries "Jonah" and "Whale" in John Kitto's Cyclopedia of Biblical Literature, and passages from Sir Thomas Browne. On Melville's use of Browne's "Of the Picture of St. George" in Vulgar Errors (Book 5) in "The Honor and Glory of Whaling," see Brian Foley, "Herman Melville and the Example of Sir Thomas Browne," Modern Philology 81 (1984), 275. It should be noted that the entry for "Hercules" in Bayle's Dictionary is notably lacking in the usual mythical stories of the Greek hero, focusing instead on his reputed "low" nature (as legendary glutton and fornicator) and apparently composite identity in some ancient traditions. Bayle cites the story of Hercules being swallowed for three days by the sea monster, but does not refer to the analogous Jonah legend; instead of being disgorged, Hercules hacks his way out of the whale's belly See "Hercules" in The Dictionary' Historical and Critical of Mr. Bayle, 5 vols. (London, 1734-38), 3:426-35. On Melville's familiarity with Bayle, see Sealts, no. 51. For more on Bayle and Moby-Dick, see Millicent Bell, "Pierre Bayle and Moby-Dick," PMLA 66 (1951), 626-48. (It is now, generally recognized that, contrary to his long-time reputation as an outspoken skeptic, Bayle was in fact a fideist for whom the inconsistencies and absurdities of religious myth only emphasized the necessity of belief.) (18) It should be noted that Ishmael presents an opposing view to Bulkington's Herculean renunciations two-thirds of the way through the narrative in "A Squeeze of the Hand" (Chapter 94). Here Ishmael elaborates on his experience squeezing the sperm oil in the whale's "case" while evoking the comforts of home: "Would that I could keep squeezing that sperm forever. For now, since by many prolonged, repeated experiences, I have perceived that in all cases man must eventually lower, or at least shift, his conceit of attainable felicity; not placing it anywhere in the intellect or fancy; but in the wife, the heart, the bed, the table, the saddle, the fireside, the country; now that I have perceived all this, I am ready to squeeze case eternally" (NN MD 416). The positive values of the shore and the claims of the heart are now given their due, though still postulated as inferior to the values of the intellect. (19) Galinsky, 7. The evolution of critical understanding of the role of myth in Melville's fiction can be found in Chase; H. Bruce Franklin, The Wake of the Gods: Melville's Mythology (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1963); Gerard M. Sweeney, Melville's Use of Classical Mythology (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1975); and Richardson, Ch. 7. On the classical dimensions to the character of Billy Budd, see Gail Coffler, "Classical Iconography in the Aesthetics of Billy Budd, Sailor," in Sten, 257-76. It is interesting to note that the most extensive use of Hercules as a heroic ideal in American literature occurs in George Cabot Lodge's 270-page epic poem, Hercules (1911). Galinsky writes that in Lodge's poem, "the final deepest questions about man's existence and fate could be expressed most worthily by being attached to Herakles.... Herakles is the timeless, universal symbol of the soul's or will's pilgrim's progress toward the final vision of the truth" (218).