NSSI and perfectionism - Victoria University of Wellington

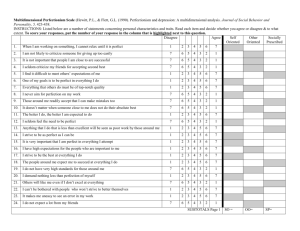

advertisement

NSSI AND PERFECTIONISM Madeleine Brocklesby Supervised by Associate Professor Marc Wilson Youth Wellbeing Study Victoria University of Wellington NON-SUICIDAL SELF INJURY “Non-suicidal self-injury is the intentional destruction of body tissue without suicidal intent and for purposes not socially sanctioned” (p. 1045, Klonsky & Muehlenkamp, 2007) • International review found that on average 18% of adolescents reported having engaged in NSSI (Muehlenkamp, Claes, Havertape & Plener, 2012) • 49% of Wellington adolescents reported having engaged in NSSI (Garisch, 2010) PERFECTIONISM “the setting of excessively high standards of performance” (p. 450, Frost, Marten, Lahart & Rosenblate, 1990) Underlying cognitive vulnerability OR a personal strength FROST’S MULTIDIMENSIONAL PERFECTIONISM SCALE (FMPS) Concerns over mistakes Doubts about actions Parental criticism Negative perfectionism Perfectionism Parental expectations Positive perfectionism Personal standards (Frost et al., 1993) Organisation (Frost et al., 1990) PREVIOUS RESEARCH Negative perfectionism Positive perfectionism Negative affect Positive affect Depression Achievement motivation Eating disorders Self esteem Anxiety disorders However….some differences across sex have been found Shame and guilt SELF-INJURY (Antony et al., 1998; Bulina, 2014; Dickie, Wilson, McDowall, & Surgenor, 2012; Frost et al., 1990; Hoff & Muehlenkamp, 2009; Klibert, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, & Saito, 2005; Stoeber, Schneider, Hussain, & Matthews, 2014) PERFECTIONISM AND NSSI • Hoff and Muehlenkamp (2009) found university students engaging in NSSI scored higher on ‘Concern over Mistakes’ and ‘Parental Criticism’, and lower on ‘Organisation’ subscales of the FMPS • O’Connor, Rasmussen and Hawton (2010) illustrated that for adolescents experiencing only low levels of life stress, an increase in negative perfectionism significantly increased the probability of engaging in deliberate self-harm. THE YOUTH WELLBEING STUDY Aim: to clarify the relationship between NSSI and negative and positive components of perfectionism in adolescents 15 secondary schools >900 students 13-15 years old 58.8% male; 41.2% female Deliberate Self Harm Inventory – 14 specific NSSI behaviours (DSHI; Gratz, 2001) Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale – 35 items (FMPS; Frost et al., 1990) HYPOTHESES • A factor analysis will produce two distinct sub-factors of perfectionism; positive perfectionism and negative perfectionism • Adolescents reporting high negative perfectionism will report more NSSI, whereas individuals high on positive perfectionism will report less NSSI • Sex differences may be found in this relationship FINDINGS HYPOTHESIS ONE: 2 factors within perfectionism • Uncertainty of the applicability of Frost’s six factors in the current sample • Two factor, positive/negative structure supported • Consistent with other studies using the FMPS in adolescent samples (e.g. Cox, Enns, & Clara, 2002; Hawton, Saunders, & O’Connor, 2012; Khawaja & Armstrong, 2005; Thorpe & Nettelbeck, 2014) SOME GENERAL FINDINGS Perfectionism • Positive perfectionism was higher than negative perfectionism in both males and females • Females scored higher than males on both negative and positive perfectionism NSSI • 21.1% of the sample had engaged in NSSI, 9.9% had thought about (but not done) it • Females (29%) engaged in significantly more NSSI than males (9%) FINDINGS HYPOTHESIS TWO: negative perfectionism = risk of NSSI positive perfectionism = risk of NSSI • Negative perfectionism was positively related to NSSI (r = .31, p<.001) • There was a weak negative relationship between positive perfectionism and NSSI (r = -.13, p<.001) FINDINGS HYPOTHESIS THREE: Sex differences may be found in the relationship between NSSI and perfectionism • Females • Positive perfectionism and NSSI (r = -.18, p<.001) • Negative perfectionism and NSSI (r = .34, p<.001) • Males • Positive perfectionism and NSSI (r = -.14, p<.01) • Negative perfectionism and NSSI (r = .11, p=.04) FINDINGS 0.5 • Sex moderated the 0.3 Female NSSI relationship between negative perfectionism and NSSI 0.4 Male 0.2 0.1 0 Low Medium Negative Perfectionism High IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCHERS, CLINICIANS, PARENTS AND SCHOOL STAFF • Research should continue to differentiate between positive and negative perfectionism rather than use an overall perfectionism score • Awareness that negative perfectionism could significantly contribute to a female adolescents risk of engaging in NSSI • Parents and teachers can limit the development of negatively perfectionistic beliefs in adolescents by attending to how they frame their expectations (Damian, Stoeber, Negru, Bǎban, & Băban, 2013) • Interventions for NSSI should consider perfectionistic beliefs FUTURE RESEARCH • Investigate whether alternative factor structures of the FMPS provide a better fit for our adolescent sample • Examine whether there are functions of NSSI that are especially relevant for individuals high on perfectionism e.g. self-punishment, gain a sense of control, reduce the expectations of others Thank you! REFERENCES Antony, M. M., Purdon, C. L., Huta, V., Richard, P. S., Swinson, R. P., & Richard, P. S. (1998). Dimensions of perfectionism across the anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(12), 1143–1154. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00083-7 Bulina, R. (2014). Relations Between Adaptive and Maladaptive Perfectionism, Self-Efficacy, and Subjective Well-Being, 4(10), 835–842. Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Clara, I. P. (2002). The multidimensional structure of perfectionism in clinically distressed and college student samples. Psychological Assessment, 14(3), 365–373. http://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.14.3.365 Damian, L. E., Stoeber, J., Negru, O., Bǎban, A., & Băban, A. (2013). On the development of perfectionism in adolescence: Perceived parental expectations predict longitudinal increases in socially prescribed perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(6), 688–693. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.021 Dickie, L., Wilson, M., McDowall, J., & Surgenor, L. J. (2012). What Components of Perfectionism Predict Drive for Thinness? Eating Disorders, 20(March 2014), 232–247. http://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2012.668484 Frost, R. O., Heimberg, R. G., Holt, C. S., Mattia, J. I., & Neubauer, A. L. (1993). A comparison of two measures of perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 14(1), 119–126. http://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(93)90181-2 Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 449– 468. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF01172967 Garisch, J. A. (2010). Youth deliberate self-harm : Interpersonal and intrapersonal vulnerability factors , and constructions and attitudes within the social environment ., 1–319. Gratz, K. L. (2001). Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(4), 253–263. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012779403943 Hawton, K., Saunders, K. E. a, & O’Connor, R. C. (2012). Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet, 379(9834), 2373–2382. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5 Hoff, E. R., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2009). Nonsuicidal self-injury in college students: the role of perfectionism and rumination. Suicide & LifeThreatening Behavior, 39, 576–587. http://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2009.39.6.576 Khawaja, N. G., & Armstrong, K. A. (2005). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale: Developing shorter versions using an Australian sample. Australian Journal of Psychology, 57(2), 129–138. http://doi.org/10.1080/10519990500048611 Klibert, J. J., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., & Saito, M. (2005). Adaptive and maladaptive aspects of self-oriented versus socially prescribed perfectionism. Journal of College Student Development, 46(2), 141–156. http://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2005.0017 Klonsky, E. D., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2007). Self‐injury: A research review for the practitioner. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(11), 1045– 1056. http://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20412 Muehlenkamp, J. J., Claes, L., Havertape, L., & Plener, P. L. (2012). International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6(10), 1–9. http://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-6-10 O’Connor, R. C., Rasmussen, S., & Hawton, K. (2010). Predicting depression, anxiety and self-harm in adolescents: The role of perfectionism and acute life stress. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(1), 52–59. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.008 Stoeber, J., Schneider, N., Hussain, R., & Matthews, K. (2014). Perfectionism and Negative Affect After Repeated Failure. Journal of Individual Differences, 35(2), 87–94. http://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000130 Thorpe, E., & Nettelbeck, T. (2014). Testing if Healthy Perfectionism Enhances Academic Achievement in Australian Secondary School Students. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 4(2), p1. http://doi.org/10.5539/jedp.v4n2p1