PKU - WordPress.com

advertisement

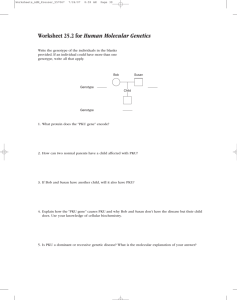

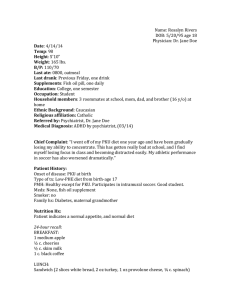

Sarah Lopes Human Genetics Mariluci Bladon Due: 5/14/12 Phenylketonuria Phenylketonuria (PKU) is a genetic disorder involving mutation of the phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) gene, rendering the liver enzyme PAH nonfunctional and causing inability to metabolize the essential amino acid phenylalanine (PHE). When PHE accumulates in the body unmetabolized, it is harmful to the central nervous system and causes brain damage. A diagnosis of PKU is given when blood levels of PHE exceed 12 mg/dl on a regular diet.1 PKU is an autosomal recessive disorder, meaning that offspring must inherit the mutated gene from both parents in order to be affected. There is a 25% chance of inheriting the disease when both parents are carriers. Occurrence varies among ethnic groups and geographic regions. In the US, occurrence is approximately 1 in 16,000 births. There are varying levels of severity, the worst being Classic PKU, in which severe brain damage occurs when PHE is not avoided. Milder forms are variant PKU or non-PKU hyperphenylalaninemia. In these forms of the disease, the PAH gene mutation allows some PAH enzyme function. Blood PHE levels do not climb as high in these cases.2 Effects of PKU include mental retardation or cognitive impairment, depression, delayed social skills, hyperactivity/ADHD, microcephaly (small head), involuntary jerking movements and seizures, eczema, a “mousy” or musty odor, unusual positioning of hands, and light skin and hair.* Because phenylalanine plays a role in the body’s production of melanin, those afflicted with PKU tend to have pale skin and hair, but not as extreme as in albinism.3 In affected babies, Blood PHE levels will start to rise within 24 hours of starting to drink breast milk or formula, so testing must be performed as soon as possible to prevent possible damage. PKU testing within the first few days after birth is now a standard procedure in North America. This practice was instituted in the mid 1960s4. The baby must be drinking milk or formula for at least 24 hours in order to produce accurate results. Blood is collected via heel stick and tested for PHE levels. Less than 2 mg per deciliter is considered normal.5 Newborns found to be affected by PKU must be fed with a PHE-free formula to prevent damage in the most critical early stage of development, but may be allowed sparing portions of breast milk to be mixed with the formula. The required diet can be very challenging to follow throughout life, and without supplementation of PHE-free amino acid formulas, cutting out dietary protein will result in nutrient deficiencies. The odor and taste of these formulas can be undesirable, but they are essential to maintaining good health for those with PKU. (PKU Toolkit) Fish oil and/or iron supplements can also be beneficial.3 The correlation of dietary protein to the effects of PKU was discovered in 1951.4 The diet necessary for controlling PKU greatly reduces or eliminates proteins naturally found in food, whether from animal or plant sources, because they all contain PHE as a building block. The safest foods to eat are non-starchy vegetables, fruits, natural sweeteners such as sugar and honey, and special low-protein breads and pastas. All meat products, including steak or beef, pork, poultry, fish and shellfish, must be avoided, along with eggs, dairy products, legumes, nuts, seeds, beans, and soy. Aspartame, an artificial sweetener commonly known as NutraSweet, must also be avoided, as it is composed of phenylalanine and aspartic acid. Starchy foods such as potatoes, corn, peas, and common varieties of breads and pastas contain a fair amount of protein and should be consumed very sparingly in measured amounts or avoided. It was once thought that returning to a relatively normal diet was safe once the affected individual reached childhood or adolescence, but now the standard recommendation is “diet for life”. While the most important time to follow the diet is in infancy when the brain is developing, and irreversible mental retardation will most likely result if the diet is not followed, consuming PHE-containing foods later in life causes problems with paying attention, concentrating, and remembering. Going back “on diet” typically reverses this effect.2 Maternal PKU must be handled very carefully with a controlled diet in order for the fetus to develop normally, even when the fetus is heterozygous and therefore unaffected by the disease. If the mother is not following a PHE-free diet, the fetus is exposed to high enough levels of PHE in utero to cause mental impairment, low birth weight, heart defects, and microcephaly. In a study involving 53 children born to 22 PKU-affected mothers at the PKU Clinic of Children’s Hospital, Dr. Harvey Levy and Dr. Susan Waisbren determined that the IQ of the offspring was “significantly correlated with both maternal IQ and maternal blood phenylalanine level.” Mental retardation in the offspring was found to be consistent when the maternal PHE level exceeded 18 mg per deciliter.6 In 2005, a breakthrough PKU research paper was published by gene therapist Dr. Savio Woo and his post-doctoral students Li Chen and Zhiyu Li at Mt Sinai School of Medicine. Dr. Woo’s students claimed to have cured PKU in mice using a gene insertion technique with the use of a viral enzyme. When the findings could not be replicated by other researchers, the matter was investigated and the post-doctoral students were found to have engaged in scientific misconduct. The paper, along with others, was regretfully retracted by Dr. Woo.7 Much focus has been placed upon enzyme replacement therapy as a treatment for PKU. PAH, the naturally occurring liver enzyme produced by normal individuals, is unstable and has many complex functional requirements. PAH has been administered to PKU mice in clinical studies, and although the initial response was positive, this was short lived, as an immune response quickly rendered the foreign enzyme ineffective. Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), an enzyme derived from plant, fungi, or bacterial sources, appears to be more promising. PAL is a more stable enzyme, and unlike PAH, it does not require a cofactor to function. It can convert the excess phenylalanine to trans-cinnamic acid and ammonia, which are both harmless. As one might expect, however, PAL proved to be immunogenic as well. In fact, the PAL enzyme was effective for no longer than 1 week in PKU mouse models with repeated dosing.8 PEGylation is a process of attaching polyethylene glycol to a drug or therapeutic protein in order to camouflage and protect them from degradation by immune response. PEGylated PAL (PEG-PAL) has been shown to have substantially reduced immunogenicity, and long-term use of PEG-PAL has been successful in reducing PEH levels in mouse models. Because polyethylene glycol is harmless to the body, the PAG-PAL compound is injected subcutaneously for direct absorption into the blood.9,10 Phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) Sapropterin dihydrochloride (brand name Kuvan) is relatively new drug is now available to help keep PHE blood levels low. It is a synthetic version of the cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). It is intended to be used in conjunction with a proper diet, rather than to allow consumption of off-limit foods. Unfortunately, it is not effective for all individuals with PKU. Those for whom the drug is beneficial are considered to be “BH4-responsive.” Some studies have shown that mild cases are the best candidates, and effectiveness tapered off over time. Furthermore, PKU News advises: “Even if BH4 treatment is found to be effective, cost is an issue. For a 10 mg/kg dose, it would cost more than $7,000 yearly for a 1-3 year old child; for a school-age child, more than $14,000; for a teenager/adult, $35-40,000 or more per year. This does not include any formula that may still be necessary.”11,12,13 Total enzyme replacement therapy may never be feasible for those with PKU, either due to difficulties with administering the enzymes or high cost. However, the ability to manage PKU and avoid mental retardation simply by following a protein-restricted diet is quite miraculous. References: 1. Waisbren, S.E., Doherty, L.B., Bailey, I.V., Rohr, F.J., Levy, H.L. (1988) The New England Maternal PKU Project: Identification of At-Risk Women. American Journal of Public Health. Vol. 78 No. 7. 2. Phenylketonuria. Genetics Home Reference. Found online at http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/phenylketonuria. Retrieved March 15, 2012. 3. Phenylketonuria. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Found online at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0002150/. Retreived March 15, 2012. 4. Levy, H.L. (1999) Phenylketonuria: Old disease, new approach to treatment. PNAS – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 5. Phenylketonuria (PKU) Test. Web MD. Found online at http://www.webmd.com/parenting/baby/phenylketonuria-pku-test. Retreived March 15, 2012. 6. Levy, H.L., Waisbren, S.E. (1983) Effects of Untreated Maternal Phenylketonuria and Hyperphenylalaninemia on the Fetus. New England Journal of Medicine. 309: 1269-1274. 7. Stone, J. (2010) US ‘gene therapy’ scientists forced to retract papers. BioNews. 577 8. Shedlovsky, A., McDonald, J. D., Symula, D., and Dove, W.F. (1993) Mouse Models of Human Phenylketonuria. Genetics Society of America. 9 Sarkissian, C.N., Adams, J., Gámez, A. (2009) Explanation of PEG-PAL. Canadian PKU and Allied Disorders Inc. 10. Sarkissian, C.N., Gámez, A., Wang, L., Charbonneau, M., Fitzpatrick, P., Lemontt, J.F., Zhao, B., Vellard, M., Bell, S.M., Henschell, C., Lambert, A., Tsuruda, L., Stevens, R.C., Scriver, C.R. (2008) Preclinical evaluation of multiple species of PEGylated recombinant phenylalanine ammonia lyase for the treatment of phenylketonuria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 20894-9. 11. Sapropternin. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Found online at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a608020.html. Retrieved May 7, 2012. 12. Harding, C.O. (2010) New era in treatment for phenylketonuria: Pharmacologic therapy with sapropterin dihydrochloride. Biologics. 4: 231-236. Dove Medical Press Ltd. 13. Schuett, V. (2003) Will Tetrahydrobiopterin Have A Role In PKU Treatment? National PKU News. Spring/Summer.