Style E 36 by 48 - User Homepages @Drew University

advertisement

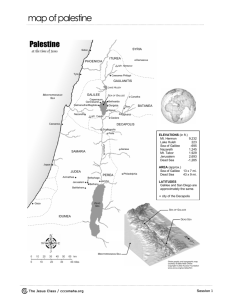

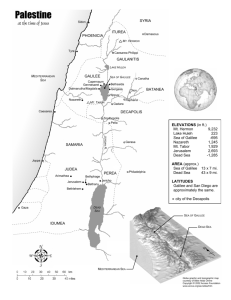

Jewish Bethsaida Carl Savage Drew University and the Bethsaida Excavations Project Knife–pared “Herodian” oil lamp Limestone or chalk vessels Background Local ware Balloon photo of Tell-Bethsaida Rhodian Amphora and Storage jars Contribution of Research Research Hypothesis The application of literature to social reconstruction leads to many views of the “landscape”[1] of the first century, the textual topography.[2] For example, on one side of the spectrum we see painted a portrait of an environment “that was to a considerable degree dominated by the Greek and Roman mind.”[3] So much so in fact that Jesus was at great pains to avoid the Gentile element in Galilee.[4] At another point along the spectrum it is suggested that only the “thinnest veneers” of Judaism was applied to the Gentile heartland of the “Galilee of the Gentiles”.[5] “The claim is typical...a casual perusal reveals that many report a strong gentile presence, sometimes a majority, sometimes a large and highly visible minority. According to this view, Galilee’s large pagan population explains why Matthew 4:15 refers to the region as ‘Galilee of the Gentiles’…..”[6] What is lacking is any check and balance with the material culture that is found. What has been discovered I discovered a collection of limestone or chalk vessel fragments which are important indicative pieces for Jewish presence in the Roman period. There are not many items that would serve as definite ethnic markers for first century Jews or Christians. At Bethsaida we have discovered examples of five of the eight categories of objects held to be indicative of Jewish presence: Galilean Coarse Ware, Hasmonean coins, stone vessels, Kefar Hannania ware, including the “Galilean bowl”; and possibly a secret hideaway. From among the eight markers, one has been determined to be more significant for late Second Temple Judaism. Yitzhak Magen describes that status this way: ”Unlike other elements of the Jewish material culture during the Second Temple period, such as pottery, wooden, metal and glass vessels and other implements that were conceived in previous periods and that remained a part of the material culture after the destruction of the Temple, chalk vessels are the only components of the material culture that appear suddenly in the late first century BCE and vanish after the destruction of the Second Temple and the Bar Kochba Revolt, without remaining in use and without returning to the material culture of the Land of Israel in succeeding periods.”[7] Stuart S. Miller also notes concerning stone vessels: “They are found largely at sites that we know, from either literary or archaeological sources--or both--were Jewish. This, it would seem, is convincing enough reason to assign to them the role of an identification marker denoting a Jewish site.” .[8] The Excavations In 1987, Israeli archaeologist Dr. Rami Arav undertook a ten-day probe of et-Tell (literally "the mound") to determine if the 21 acre site was indeed Bethsaida. In addition to the Hellenistic-Roman city of Bethsaida, in 1996, the remains of an Iron Age (time of Hebrew Bible) City Gate complex were uncovered. Drew University has been part of the Bethsaida Excavations Project since 1997 Acknowledgments Christine Dalenta, University of Hartford, photography Paul Bauman, Komex International, balloon photography Priscilla Patten Benham Dissertation Research Prize Edward D. Zinbarg Prize; The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Carl Savage holding a Galilean Bowl fragment Idols mainly from 3rd-1st century BCE Conclusions This study engages in the process of constructing a portrait of Galilee. Drawing from archaeological evidence at Bethsaida, a place named in the gospels and by Josephus, it attempts to reconstruct the perspective of the ancient inhabitants of Galilee through their material practices which are indications of their sense of “place” both ideologically and geographically. They were involved in creating, accommodating, and resisting the competing influences and powers that shaped their first century CE world. Essentially, it is that world that the various attempts at reconstruction of the first century CE world seek to approximate. What does an overview of archaeological remains contribute to this discussion? Most important is the recognition that material culture of household Judaism reflects behaviors and attitudes held in common. That is, the patterns we discover in the material culture can allow us to see what was held in common, the consensual culture. We see beginning in the first half of the first century BCE and developing and solidifying into the first century CE, markers that indicate a conscious self-identity for Jews in Galilee. There is evidence from the material culture of a shared symbolic world-view. In their daily lives most Jews were more alike than different among themselves, and certainly more different than alike compared to the greater Hellenistic culture around them. There appear several distinctive self-identifying markers in the material culture: limestone vessels; the avoidance of decorated pottery, evidenced by the change in oil lamp typology and in the production of Jewish household ware that was mostly differentiated from its Hellenistic counterpart by absence of decoration more so than by variation in form; absence of a certain type of cooking vessel, the pan, indicative of a difference in ethnic cooking; and the presence of miqvot (Jewish ritual baths). These artifacts and special architectural features illustrate a behavior pattern that is resistive to the hellenistic patterning of life, and indicative of a Galilee that is Jewish. Bethsaida Located 2 km from the northeastern coast of the Sea of Galilee in Israel Mentioned frequently in the New Testament The ancient Jewish historian, Josephus Flavius, recounts that in the year 30 CE, Phillip, the son of Herod the Great, raised the village of Bethsaida to the status of a Greek city and renamed it Julias Kefar Hannania Ware Jewish Coins 1st C BCE & CE Rhodian Amphora Because of the nature of archaeological argument from the slim residues of cultural behaviors found in limited numbers of recovered artifacts, one need be circumspect when interpreting toward a given hypothesis. The danger is always to argue selectively from the record ignoring data that does not fit one’s desired view of the first-century context. Also, one may tend to attach a substantiation to behavior to a particular class of artifact that may outweigh any reasonable alternative explanation. What is clear at Bethsaida is that when one examines the entire archaeological context recovered from the site a well-defined shift from one cultural orientation to another occurs during the transition from Hellenistic to early Roman periods. When the data has been thoroughly read, the image of first century Bethsaida that emerges is one that is at home in the gallery of a Jewish Galilee. Far from being subdued and dominated by a harsh anti-Jewish Hellenism, one finds a community at Bethsaida in the first century CE that is mostly Jewish while at the same time expressing its life pathways via contemporary cultural forms Further Information http://users.drew.edu/csavage/ http://www.unomaha.edu/bethsaida/ http://uhaweb.hartford.edu/mgarchive/bethsaida Bibliography [1] James Strange following the work of Mariane Sawieki notes concerning Josephus’ view of the Galilee in his Vita : “Josephus’ description of Galilee in the Vita exhibits a kind of urban bias, if you will, a detectable ‘mindscape.’” He notes that Josephus is not interested in merely purveying the geophysical landscape, nor even the social-economic relationships among the various parties inhabiting Galilee. He really intends to portray two main cities of Galilee, secundum and Tiberias, as the stage upon which “he acted out his roles as general, aristocrat, and representative of virtue.” James F. Strange, Secundum and Galilee in Josephus’ Vita, Papers of the SBL Josephus Seminar, 1999–2004 (2001), Http://pace.cns.yorku.ca/York/york/conference2001-ext.htm. [2] Marianne. Sawicki, Crossing Galilee Architectures of Contact in the Occupied Land of Jesus (Harrisburg, Pa.: Trinity Press International, 2000), 37; Sean. Freyne, “Galilee-Jerusalem Relations According to Josephus’ Life,” New Testament Studies 33 (1987): 600–09 Both authors examine the idea of any depiction of landscape as “mindscape,” that is, a presentation of geography that also portrays the cultural understanding of it. [3] Abraham J. Malherbe, “Life in the Greco-Roman World,” in The World of the New Testament (Austin, TX: R.B. Sweet Co., Inc., 1967), 4. [4]Abraham J. Malherbe, “Life in the Greco-Roman World,” 5. [5]Burton L. Mack, The Lost Gospel the Book of Q & Christian Origins (San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993), 53. [6] Mark A. Chancey, The Myth of a Gentile Galilee: The Population of Galilee and New Testament Studies (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 15 Mark Chancey notes two works which summarize and support this view: G. H. Boobyer, Galilee and Galileans in St. Mark’s Gospel. (1953), 334–58; and Bo Ivar Reicke, The New Testament Era the World of the Bible from 500 B.C. to A.D. 100 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1968), 117. [7] Yitzhak Magen, The Stone Vessel Industry in the Second Temple Period (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2002), 100. [8] Stuart S. Miller, “Some Observations on Stone Vessel Finds and Ritual Purity in Light of Talmudic Sources,” in Zeichen Aus Text und Stein, Stefan Alkier and Jürgen Zangenberg (Tübingen: Francke Verlag, 2003), 403.