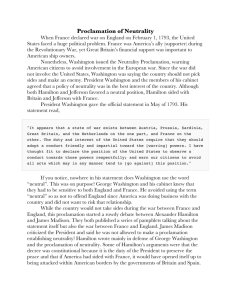

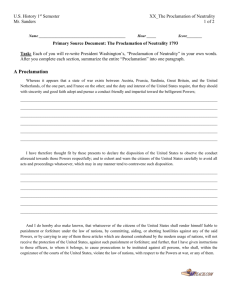

Documentation #4: The Proclamation on Neutrality Sydney Rivera

advertisement

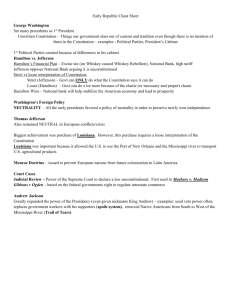

Documentation #4: The Proclamation on Neutrality Sydney Rivera-Gatins The Proclamation of Neutrality is a government document written in 1793 to formally announce America’s neutrality on the European war, declaring the nation will not participate in the war and will take legal action against any American who provides assistance to any and all countries involved in the war. While the document is signed by George Washington, the President of the United States of that time, I would argue members of his cabinet to be the official writer’s of the document. George Washington was aware of his strengths and weaknesses as the American leader and owed much of his success brilliance to his contemporaries (Brands Ch. 7, section 1). I would speculate the author(s) to be members of his cabinet, singularly Hamilton, a member of his Cabinet who was a large supporter of the move to proclaim neutrality and brilliant writer. The state of war, acknowledged in the document, included Great Britain, Austria, Prussia, Sardinia, United Netherlands and France so, technically, the proclamation was for all powers involved. However, the proclamation was particularly targeted for France and Great Britain as the relationships to the two countries were delicate regarding economy and the newfound independence of America. The American shipping and trading with Europe was challenged with these powerful European countries at war (Brands Ch.7, section 3) and their was confusion regarding the whether America was legally bound by the 1778 Franco-American Treaty to supply France against Britain. George Washington and his cabinet were in agreement that neutrality was the best position for America as they were too young and their military too vulnerable in stature to risk engagement, although, the cabinet itself was at odds as to, if coerced, which European power, France or Britain, they should ultimately aid to maintain peace on America soil and keep their economy and European trade afloat. As mentioned prior, the decision for American neutrality was unanimously agreed upon between Washington and his cabinets, however, the formality of the proclamation with this document was not. Jefferson acknowledged and did not trust Hamilton and his companion’s alterior motives with such a proclamation. He did not see it as a choice made in the best interest in the country but in Hamilton’s interests, to placate Britain ultimately. Jefferson believed the formal announcement would close the advantage of America watching which of the European countries will ultimately help America’s growth by their actions and then assess how to reply. Hamilton believed America should appease the former mother country, even at the price of his nation’s pride (Brands Ch. 7, section 3). I would describe Hamilton’s tactics distrustful and that, based on other documentation of his actions such as undermining the success of Jay’s Treaty, Jefferson’s suspicion of ulterior motive was spot on. This document, by itself, is straightforward and applies a sober and sound decision. The rich controversy around it, the enormous rift between members of the cabinet and the lack of true democracy of that decision is an unfortunate similarity in today’s politics. The ability for polarization in our Democracy is necessary. The freedom of speech and the freedom of political party choice is an example. The polarity within a cabinet at a time where foreign policy is at stake is something that enraged the people of America in 1793 and continues with American citizens today. I equate the current neutrality claims of America with Israeli/Palestine war with the history of America’s neutrality with France and Britain. Since 1948, both political parties have refused to recognize Jerusalem as Israel territory as a form of neutral policy, however, it is known that if the future were to ask the United State’s to recognize Jerusalem as Palestine territory with a peace agreement, that would not happen. One can also identify the billions of dollars the United States give to Israel as aid to support their fourth most powerful military in the world. The House speaker Nancy Pelosi was recently quoted,” In Congress, we speak with one voice on the subject of Israel.” We as a nation, supposedly have an executive branch policy of neutrality in regards to the Middle East conflict. However, even with such a policy in place, the congress and the Obama administration showed conflicting perspectives on such a policy when an American boy was born in Jerusalem and the decision of what to put as the place of birth on his passport became controversial. Do you think it should be documented as just Jerusalem, or Jerusalem, Israel, or even yet, Jerusalem, Palestine? Should the family be able to list the place according to their beliefs or the United States’ identification of the birthplace and, if so, what would that be if the nation’s stand were not to undermine the rivaled countries their own negotiations? The debate was pitted between the enacted legislation of Congress originally allowing for the birthplace to be acknowledged as Israel territory and the Obama administration. It was decided as such: U.S. court Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit unanimously affirmed the State Department’s refusal to allow the parents of the boy born in Jerusalem to list his birthplace “Jerusalem, Israel”. In doing so, the court declared the 2002 law that directed the secretary of State to originally allow the birthplace to be identified as Israel, unconstitutional. Millions of American dollars at work for the political intricacies of pretending to be a neutral bystander in the Israeli/Palestine war. Why did Washington refuse to protect any Americans who aided the warring nations? The offer was to prove the US’s neutrality by declaring that due consequences would be performed should an American citizen show or attempt any assistance to either Powers involved in the war. The same proclamation was made if a US citizen was to be hostile to any Powers in the war. The proclamation was controversial among the people because of their recognition that the French helped the United States in the war of their freedom. Jeffersonians, in particular, may have believed, like Jefferson himself, it was preposterous that we not return the favor. Washington and the cabinet wanted to put out such fires with the threat of legal consequences. Hamilton believed when the French helped the United State they had advantages to do so but the war that they were in was not advantages to America. Arguably, the fact that America wished to continue trading with the Europeans while the countries, to announce refusal of protection to any Americans who aided warring nations was a way for the American trading ships to be able to land on Britain and French ports without retaliation. George Washington reflected on the cabinets answers to his thirteen questions he gave them and concluded the war was a European war and since America was on a different continent, not a part of European soil this war was not his nation’s fight. Who were the major belligerents in the European war? Though Austria, Prussia and Sardina are included in the war with Britain against France, the belligerent countries were Britain and France. However, the French people in particular took a highly aggressive approach later titled the Reign of Terror. Two political factions instigated this period of violence with their rivalry: the Girondins and the Jacobins (linked to the faction Mountains) (Linton, Ch 1). The Girondins, led by JacquesPierre Brissot, were the dominant faction when the Jacobins overthrew the monarchy. The quote, “The guillotine stands as the principal symbol of the Terror in the French Revolution” (Hanson p.151) poignantly describes how the many were executed. The death toll ranged in the high ten thousands, 16,594 executed by guillotine and about 25,000 more across France. The abhorrent violence seems to have come from high levels of frustration of the French people and ultimately seeing popular violence as their political right. Brands, Breen, Williams, Gross American Stories: A History of the United States, Vol. 1, 3rd edition Paul R. Hanson (2007). The A to Z of the French Revolution. Scarecrow Press. p. 151. Linton, Marisa. "The Terror in the French Revolution" (PDF). Kingston University. Retrieved 2 December 2011. http://articles.latimes.com/2013/jul/25/opinion/la-ed-jerusalem-israel-passport-20130725 http://www.palestinechronicle.com/how-neutral-is-us-neutrality-in-the-middle-east/