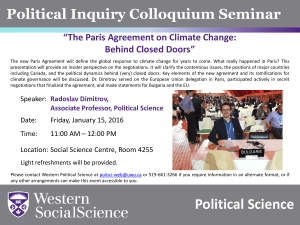

File - Fortismere A level Art history

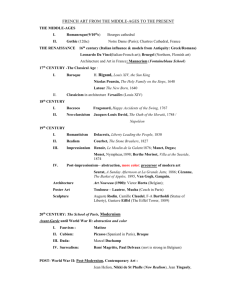

France emerges during this period as a major world power and a cultural center to rival

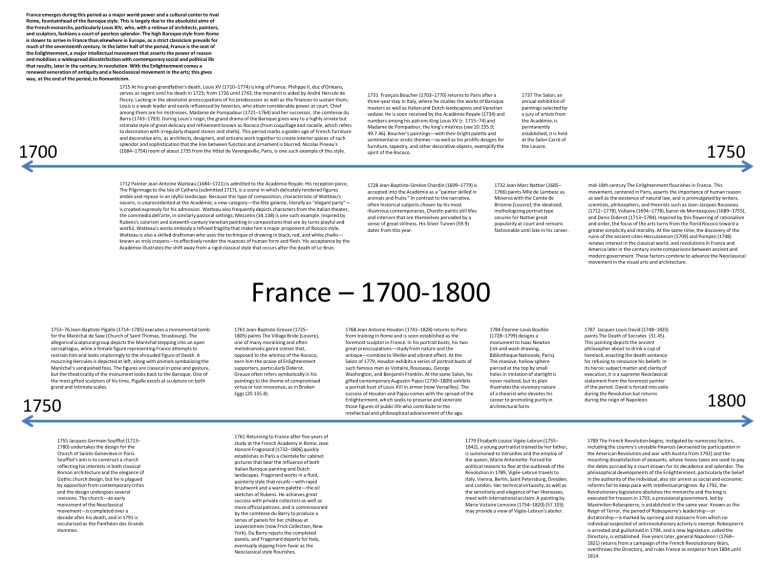

Rome, fountainhead of the Baroque style. This is largely due to the absolutist aims of the French monarchs, particularly Louis XIV, who, with a retinue of architects, painters, and sculptors, fashions a court of peerless splendor. The high Baroque style from Rome is slower to arrive in France than elsewhere in Europe, as a strict classicism prevails for much of the seventeenth century. In the latter half of the period, France is the seat of the Enlightenment, a major intellectual movement that asserts the power of reason and mobilizes a widespread dissatisfaction with contemporary social and political ills that results, later in the century, in revolution. With the Enlightenment comes a renewed veneration of antiquity and a Neoclassical movement in the arts; this gives way, at the end of the period, to Romanticism.

1700

1715 At his great-grandfather's death, Louis XV (1710–1774) is king of France. Philippe II, duc d'Orléans, serves as regent until his death in 1723; from 1726 until 1743, the monarch is aided by André Hercule de

Fleury. Lacking in the absolutist preoccupations of his predecessor as well as the finances to sustain them,

Louis is a weak leader and easily influenced by favorites, who attain considerable power at court. Chief among them are his mistresses, Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764) and her successor, the comtesse du

Barry (1743–1793). During Louis's reign, the grand drama of the Baroque gives way to a highly ornate but intimate style of great delicacy and refinement known as Rococo (from coquillage and rocaille, which refers to decoration with irregularly shaped stones and shells). This period marks a golden age of French furniture and decorative arts, as architects, designers, and artisans work together to create interior spaces of such splendor and sophistication that the line between function and ornament is blurred. Nicolas Pineau's

(1684–1754) room of about 1735 from the Hôtel de Varengeville, Paris, is one such example of this style.

1731 François Boucher (1703–1770) returns to Paris after a three-year stay in Italy, where he studies the works of Baroque masters as well as Italian and Dutch landscapists and Venetian vedute. He is soon received by the Académie Royale (1734) and numbers among his patrons King Louis XV (r. 1715–74) and

Madame de Pompadour, the king's mistress (see 20.155.9;

49.7.46). Boucher's paintings—with their bright palette and sentimental or erotic themes—as well as his prolific designs for furniture, tapestry, and other decorative objects, exemplify the spirit of the Rococo.

1737 The Salon, an annual exhibition of paintings selected by a jury of artists from the Académie, is permanently established; it is held at the Salon Carré of the Louvre.

1712 Painter Jean Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) is admitted to the Académie Royale. His reception piece,

The Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera (submitted 1717), is a scene in which delicately rendered figures amble and repose in an idyllic landscape. Because this type of composition, characteristic of Watteau's oeuvre, is unprecedented at the Académie, a new category—the fête galante, literally an "elegant party"— is created expressly for his admission. Watteau also frequently depicts characters from the Italian theater, the commedia dell'arte, in similarly pastoral settings; Mezzetin (34.138) is one such example. Inspired by

Rubens's colorism and sixteenth-century Venetian painting in compositions that are by turns playful and wistful, Watteau's works embody a refined fragility that make him a major proponent of Rococo style.

Watteau is also a skilled draftsman who uses the technique of drawing in black, red, and white chalks— known as trois crayons—to effectively render the nuances of human form and flesh. His acceptance by the

Académie illustrates the shift away from a rigid classical style that occurs after the death of Le Brun.

1728 Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779) is accepted into the Académie as a "painter skilled in animals and fruits." In contrast to the narrative, often historical subjects chosen by his most illustrious contemporaries, Chardin paints still lifes and interiors that are themselves pervaded by a sense of great stillness. His Silver Tureen (59.9) dates from this year.

1732 Jean Marc Nattier (1685–

1766) paints Mlle de Lambesc as

Minerva with the Comte de

Brionne (Louvre); the idealized, mythologizing portrait type secures for Nattier great popularity at court and remains fashionable until late in his career.

1753–76 Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (1714–1785) executes a monumental tomb for the Maréchal de Saxe (Church of Saint Thomas, Strasbourg). The allegorical sculptural group depicts the Maréchal stepping into an open sarcophagus, while a female figure representing France attempts to restrain him and looks imploringly to the shrouded figure of Death. A mourning Hercules is depicted at left, along with animals symbolizing the

Maréchal's vanquished foes. The figures are classical in pose and gesture, but the theatricality of the monument looks back to the Baroque. One of the most gifted sculptors of his time, Pigalle excels at sculpture on both grand and intimate scales.

1750

1755 Jacques-Germain Soufflot (1713–

1780) undertakes the design for the

Church of Sainte-Geneviève in Paris.

Soufflot's aim is to construct a church reflecting his interests in both classical

Roman architecture and the elegance of

Gothic church design, but he is plagued by opposition from contemporary critics and the design undergoes several revisions. The church—an early monument of the Neoclassical movement—is completed over a decade after his death, and in 1791 is secularized as the Panthéon des Grands

Hommes.

1750 mid-18th century The Enlightenment flourishes in France. This movement, centered in Paris, asserts the importance of human reason as well as the existence of natural law, and is promulgated by writers, scientists, philosophers, and theorists such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau

(1712–1778), Voltaire (1694–1778), baron de Montesquieu (1689–1755), and Denis Diderot (1713–1784). Inspired by this flowering of rationalism and order, the focus of the arts turns from the florid Rococo toward a greater simplicity and morality. At the same time, the discovery of the ruins of the ancient cities Herculaneum (1709) and Pompeii (1748) renews interest in the classical world, and revolutions in France and

America later in the century invite comparisons between ancient and modern government. These factors combine to advance the Neoclassical movement in the visual arts and architecture.

France – 1700-1800

1761 Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–

1805) paints The Village Bride (Louvre), one of many moralizing and often melodramatic genre scenes that, opposed to the whimsy of the Rococo, earn him the praise of Enlightenment supporters, particularly Diderot.

Greuze often refers symbolically in his paintings to the theme of compromised virtue or lost innocence, as in Broken

Eggs (20.155.8).

1768 Jean Antoine Houdon (1741–1828) returns to Paris from training in Rome and is soon established as the foremost sculptor in France. In his portrait busts, his two great preoccupations—study from nature and the antique—combine to lifelike and vibrant effect. At the

Salon of 1779, Houdon exhibits a series of portrait busts of such famous men as Voltaire, Rousseau, George

Washington, and Benjamin Franklin. At the same Salon, his gifted contemporary Augustin Pajou (1730–1809) exhibits a portrait bust of Louis XVI in armor (now Versailles). The success of Houdon and Pajou comes with the spread of the

Enlightenment, which seeks to preserve and venerate those figures of public life who contribute to the intellectual and philosophical advancement of the age.

1784 Étienne-Louis Boullée

(1728–1799) designs a monument to Isaac Newton

(ink and wash drawing,

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris).

The massive, hollow sphere pierced at the top by small holes in imitation of starlight is never realized, but its plan illustrates the visionary nature of a theorist who devotes his career to promoting purity in architectural form.

1761 Returning to France after five years of study at the French Academy in Rome, Jean

Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) quickly establishes in Paris a clientele for cabinet pictures that bear the influence of both

Italian Baroque painting and Dutch landscapes. Fragonard works in a fluid, painterly style that recalls—with rapid brushwork and a warm palette—the oil sketches of Rubens. He achieves great success with private collectors as well as more official patrons, and is commissioned by the comtesse du Barry to produce a series of panels for her château at

Louveciennes (now Frick Collection, New

York). Du Barry rejects the completed panels, and Fragonard departs for Italy, eventually slipping from favor as the

Neoclassical style flourishes.

1787 Jacques Louis David (1748–1825) paints The Death of Socrates (31.45).

This painting depicts the ancient philosopher about to drink a cup of hemlock, enacting the death sentence for refusing to renounce his beliefs. In its heroic subject matter and clarity of execution, it is a supreme Neoclassical statement from the foremost painter of the period. David is forced into exile during the Revolution but returns during the reign of Napoleon.

1800

1779 Élisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun (1755–

1842), a young portraitist trained by her father, is summoned to Versailles and the employ of the queen, Marie Antoinette. Forced for political reasons to flee at the outbreak of the

Revolution in 1789, Vigée-Lebrun travels to

Italy, Vienna, Berlin, Saint Petersburg, Dresden, and London. Her technical virtuosity, as well as the sensitivity and elegance of her likenesses, meet with international acclaim. A painting by

Marie Victoire Lemoine (1754–1820) (57.103) may provide a view of Vigée-Lebrun's atelier.

1789 The French Revolution begins, instigated by numerous factors, including the country's unstable finances (worsened by participation in the American Revolution and war with Austria from 1792) and the mounting dissatisfaction of peasants, whose heavy taxes are used to pay the debts accrued by a court known for its decadence and splendor. The philosophical developments of the Enlightenment, particularly the belief in the authority of the individual, also stir unrest as social and economic reforms fail to keep pace with intellectual progress. By 1792, the

Revolutionary legislature abolishes the monarchy and the king is executed for treason in 1793; a provisional government, led by

Maximilien Robespierre, is established in the same year. Known as the

Reign of Terror, the period of Robespierre's leadership—or dictatorship—is marked by uprising and massacre from which no individual suspected of antirevolutionary activity is exempt. Robespierre is arrested and guillotined in 1794, and a new legislature, called the

Directory, is established. Five years later, general Napoleon I (1769–

1821) returns from a campaign of the French Revolutionary Wars, overthrows the Directory, and rules France as emperor from 1804 until

1814.

François Boucher (P230)

François Boucher (French, 1703–1770) was a rococo painter, known for his pastoral and mythological scenes, and was one of the most celebrated decorative artists of the 18th century. Born in Paris to a lace designer, Boucher studied with painter François Le Moyne, and was influenced by his contemporary Jean Antoine Watteau.

In 1723, Boucher won the Prix de Rome, and studied in the Italian capital from 1727 to 1731. After his return to

France, he created hundreds of paintings, decorative boudoir panels, tapestry designs, theater designs, and book illustrations.

He became a faculty member at the Royal Academy in

1734, director of the Royal Gobelins Manufactory in 1755, and was made first painter to the king in 1765.

Boucher is known for his idealized and lighthearted mythological paintings and pastoral subjects, which often drew inspiration from the theater. Boucher also produced religious paintings, and was a favorite of the chief mistress to Louis XV, Madame de Pompadour.

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (P246)

He served apprenticeships with the history painters

Pierre-Jacques Cazes and Noël-Nicolas Coypel, and in 1724 became a master in the Académie de Saint-Luc.

Upon presentation of The Ray in 1728, he was admitted to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. The following year he ceded his position in the Académie de

Saint-Luc. He made a modest living by "produc[ing] paintings in the various genres at whatever price his customers chose to pay him", and by such work as the restoration of the frescoes at the Galerie François I at

Fontainebleau in 1731.

Beginning in 1737 Chardin exhibited regularly at the Salon.

He would prove to be a "dedicated academician", regularly attending meetings for fifty years, and functioning successively as counsellor, treasurer, and secretary, overseeing in 1761 the installation of Salon exhibitions.

His work gained popularity through reproductive engravings of his genre paintings, which brought Chardin income in the form of "what would now be called royalties".

In 1752 Chardin was granted a pension of 500 livres by

Louis XV. At the Salon of 1759 he exhibited nine paintings; it was the first Salon to be commented upon by Denis

Diderot, who would prove to be a great admirer and public champion of Chardin's work. Beginning in 1761, his responsibilities on behalf of the Salon, simultaneously arranging the exhibitions and acting as treasurer, resulted in a diminution of productivity in painting, and the showing of 'replicas' of previous works. In 1763 his services to the Académie were acknowledged with an extra 200 livres in pension. In 1765 he was unanimously elected associate member of the Académie des Sciences,

Belles-Lettres et Arts of Rouen, but there is no evidence that he left Paris to accept the honor. By 1770 Chardin was the 'Premier peintre du roi', and his pension of 1,400 livres was the highest in the Academy.

In 1772 Chardin's son, also a painter, drowned in Venice, a probable suicide. The artist's last known oil painting was dated 1776; his final Salon participation was in 1779, and featured several pastel studies. Gravely ill by November of that year, he died in Paris on December 6, at the age of

80.

Jean Honoré Fragonard (P261)

Fragonard was articled to a Paris notary when his father's circumstances became strained through unsuccessful speculations, but showed such talent and inclination for art that he was taken at the age of eighteen to François

Boucher. Boucher recognized the youth's rare gifts but, disinclined to waste his time with one so inexperienced, sent him to Chardin's atelier. Fragonard studied for six months under the great luminist, then returned more fully equipped to Boucher, whose style he soon acquired so completely that the master entrusted him with the execution of replicas of his paintings.

Though not yet a pupil of the Academy, Fragonard gained the Prix de Rome in 1752 with a painting of "Jeroboam

Sacrificing to the Golden Calf", but before proceeding to

Rome he continued to study for three years under

Charles-André van Loo. In the year preceding his departure he painted the "Christ washing the Feet of the

Apostles" now at Grasse Cathedral.

While at Rome, Fragonard toured Italy, executing numerous sketches of local scenery. It was in these romantic gardens, with their fountains, grottos, temples and terraces, that Fragonard conceived the dreams which he was subsequently to render in his art. He also learned to admire the masters of the Dutch and Flemish schools

(Rubens, Hals, Rembrandt, Ruisdael), imitating their loose and vigorous brushstrokes. Added to this influence was the deep impression made upon his mind by the florid sumptuousness of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, whose works he had an opportunity to study in Venice before he returned to Paris in 1761. In 1765 his "Coresus et

Callirhoe" secured his admission to the Academy. It was made the subject of a pompous (though not wholly serious) eulogy by Diderot, and was bought by the king, who had it reproduced at the Gobelins factory. Hitherto

Fragonard had hesitated between religious, classic and other subjects; but now the demand of the wealthy art patrons of Louis XV's pleasure-loving and licentious court turned him definitely towards those scenes of love and voluptuousness with which his name will ever be associated, and which are only made acceptable by the tender beauty of his color and the virtuosity of his facile brushwork; such works include the Blind Man's Bluff (Le collin maillard), Serment d'amour (Love Vow), Le Verrou

(The Bolt), La Culbute (The Tumble), La Chemise enlevée

(The Shirt Removed), and L'escarpolette (The Swing,

Wallace Collection), and his decorations for the apartments of Mme du Barry and the dancer Madeleine

Guimard.

A lukewarm response to these series of ambitious works induced Fragonard to abandon Rococo and to experiment with Neoclassicism.

The French Revolution deprived Fragonard of his private patrons: they were either guillotined or exiled. The neglected painter deemed it prudent to leave Paris in

1790 . Jean-Honoré Fragonard returned to Paris early in the nineteenth century, where he died in 1806, almost completely forgotten.

Jean Marc Nattier (P311)

He received his first instruction from his father, and from his uncle, the history painter Jean Jouvenet (1644–1717).

He enrolled in the Royal Academy in 1703 and made a series of drawing of the Marie de Médicis painting cycle by Peter Paul Rubens in the Luxembourg Palace; the publication (1710) of engravings based on these drawings made Nattier famous. He had applied himself to copying pictures at the Luxembourg Gallery, he refused to proceed to the French Academy in Rome, though he had taken the first prize at the Paris Academy at the age of fifteen. In

1715 he went to Amsterdam, where Peter the Great was then staying, and painted portraits of the tsar and the empress Catherine, but declined an offer to go to Russia.

Nattier aspired to be a history painter. Between 1715 and

1720 he devoted himself to compositions like the "Battle of Pultawa", which he painted for Peter the Great, and the

"Petrification of Phineus and of his Companions", which led to his election to the Academy.

Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (P320)

Pigalle was born in Paris, the seventh child of a carpenter.

Although he failed to obtain the Grand Prix, after a severe struggle he entered the Académie Royale and became one of the most popular sculptors of his day. His earlier work, such as Child with Cage and Mercury Fastening his

Sandals, is less commonplace than that of his more mature years, but his nude statue of Voltaire, dated 1776, and his tombs of Comte d'Harcourt, c. 1764 and of

Marshal Saxe, completed in 1777 are good examples of

French sculpture in the 18th century.

Pigalle died in Paris on 20 August 1785.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun (P356)

Born in Paris on April 16, 1755, Marie-Louise-Élisabeth

Vigée was the daughter of a portraitist and fan painter,

Louis Vigée, from whom she received her first instruction.

Her mother, Jeanne (née Maissin) was a hairdresser. Her father died when she was 12 years old. In 1768, her mother married a wealthy jeweler, Jacques-François Le

Sèvre and shortly after, the family moved to the Rue

Saint-Honoré, close to the Palais Royal. She was later patronized by the wealthy heiress Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon, wife of Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans.

During this period Louise Élisabeth benefited from the advice of Gabriel François Doyen, Jean-Baptiste Greuze,

Joseph Vernet, and other masters of the period.

By the time she was in her early teens, Louise Élisabeth was painting portraits professionally. After her studio was seized for her practicing without a license, she applied to the Académie de Saint Luc, which unwittingly exhibited her works in their Salon. In 1774, she was made a member of the Académie. On January 11, 1776 she married Jean-

Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, a painter and art dealer. Vigée Le

Brun began exhibiting her work at their home in Paris, the

Hôtel de Lubert, and the Salons she held here supplied her with many new and important contacts. Her husband's great-great-uncle was Charles Le Brun, the first Director of the French Academy under Louis XIV. Vigée-Le Brun painted portraits of many of the nobility of the day.

In 1781 she and her husband toured Flanders and the

Netherlands where seeing the works of the Flemish masters inspired her to try new techniques. There, she painted portraits of some of the nobility, including the

Prince of Nassau. In 1787, she caused a minor public scandal with a self-portrait, exhibited the same year, in which she was shown smiling open-mouthed – in contravention of painting conventions going back to antiquity. The court gossip-sheet Mémoires secrets commented: ‘An affectation which artists, art-lovers and persons of taste have been united in condemning, and which finds no precedent among the Ancients, is that in smiling, [Madame Vigée-Lebrun] shows her teeth.’

Jean-Baptiste Greuze (P276)

After a period of study in Lyon, Jean-Baptiste Greuze arrived in Paris around 1750 and entered the studio of Charles-

Joseph Natoire. He was admitted into the Académie Royale as an associate member in 1755, but did not gain full membership as an Academician until 1769. His paintings of moralizing genre subjects, exhibited at the annual Salons, earned him the praise of the influential critic Denis Diderot.

He was also a superb portraitist, exhibiting a number of portraits at the Salon throughout the 1760’s to considerable acclaim. While Greuze enjoyed the patronage of such prominent collectors as Jean de Jullienne, La Live de Jully, the

Duc de Choiseul and the Empress Catherine II of Russia, his difficult temperament often alienated other clients. Even the artist’s great champion Diderot, writing to the sculptor

Falconet in 1767, described Greuze as ‘an excellent artist, but a totally impossible person. One should collect his drawings and pictures, and leave the man alone’. Angered by the rejection of his reception piece by the Académie in 1769,

Greuze refrained from exhibiting at the Salon until 1800. His reputation suffered after the Revolution, and he died in relative obscurity.

Étienne-Louis Boullée

Born in Paris, he studied mainstream French Classical architecture in the 17th and 18th century and the

Neoclassicism that evolved after the mid century. He was elected to the Académie Royale d'Architecture in 1762 and became chief architect to Frederick II of Prussia, a largely honorary title. He designed a number of private houses from

1762 to 1778, though most of these no longer exist; notable survivors include the Hôtel Alexandre and Hôtel de Brunoy, both in Paris. Together with Claude Nicolas Ledoux he was one of the most influential figures of French neoclassical architecture.

Jean Antoine Houdon (P286)

He was born in Versailles, on 25 March 1741. In 1752, he entered the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, where he studied with Jean-Baptiste Pigalle.

Houdon won the Prix de Rome in 1761, but was not greatly influenced by ancient and Renaissance art in Rome. His stay in the city is marked by two characteristic and important productions: the superb écorché (1767), an anatomical model which has served as a guide to all artists since his day, and the statue of Saint Bruno in the church of Santa Maria degli

Angeli e dei Martiri in Rome. After ten years stay in Italy,

Houdon returned to Paris.

He submitted "Morpheus" to the Salon of 1771. He developed his practise of portrait busts. He became a member of the Académie de peinture et de sculpture in 1771, and a professor in 1778. In 1778, he modeled Voltaire, producing a portrait bust with wig for the Comédie-Française; one for the Palace of Versailles, and one for Catherine the

Great.

Jacques-Germain Soufflot

Soufflot attended the French Academy in Rome, where young French students in the 1750s would later produce the first full-blown generation of Neoclassical designers.

Soufflot's models were less the picturesque Baroque being built in modern Rome, as much as the picturesque aspects of monuments of antiquity.

After returning to France, Soufflot practiced in Lyon, where he built the Hôtel-Dieu, like a chaste riverside street facade, interrupted by the central former chapel, its squared dome with illusionistic diminishing coffers on the interior. With the Temple du Change, he was entrusted with completely recasting a 16th-century market exchange building housing a meeting space housed above a loggia. Soufflot's newly made loggia is an unusually severe arcading tightly bound between flat Doric pilasters, with emphatic horizontal lines.

He was accepted into the Lyon Academy.

A more creative trip to Italy was made when the mature

Soufflot returned in 1750. On this trip Soufflot made a special study of theaters. In 1755 Marigny, the new Director

General of Royal Buildings, gave Soufflot architectural control of all the royal buildings in Paris. In the same year, he was admitted to the Royal Academy of Architecture. In

1756 his opera house opened in Lyon.

The Panthéon is his most famous work, but the Hôtel

Marigny built for his young patron (1768–1771) across from the Élysée Palace, is a better definition of Soufflot's personal taste. Soufflot died in Paris in 1780.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (P359)

Jacques Louis David (P255)

Jacques-Louis David (30 August 1748 – 29 December 1825) was an influential French painter in the Neoclassical style, considered to be the preeminent painter of the era. In the

1780s his cerebral brand of history painting marked a change in taste away from Rococo frivolity toward a classical austerity and severity, heightened feeling[1] harmonizing with the moral climate of the final years of the

Ancien Régime.

David later became an active supporter of the French

Revolution and friend of Maximilien Robespierre (1758–

1794), and was effectively a dictator of the arts under the

French Republic. Imprisoned after Robespierre's fall from power, he aligned himself with yet another political regime upon his release, that of Napoleon I. At this time he developed his Empire style, notable for its use of warm

Venetian colours. After Napoleon's fall from power and the

Bourbon revival, David exiled himself to Brussels, then in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, where he remained until his death. David had a large number of pupils, making him the strongest influence in French art of the early 19th century, especially academic Salon painting.