The Changing Practice of Medicine and its Ethics

advertisement

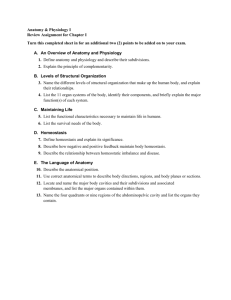

The Changing Practice of Medicine (And things you wish you didn’t know) HCMG 300, Fall 2014 October 6, 2014 Jen Early, Doctoral Candidate, MSHA, RN Virginia Commonwealth University, Department of Health Administration 1 Objectives • Historical evolution of the study of the human body • Overview of evolution of medical education in US in light of co-evolving ethical issues 2 Historical Study of the Human Body1 • Medicine is the study of disease and its treatments • To study disease, physicians focus on abnormalities of structure (i.e. anatomy) and function (i.e. physiology) • For a long time, structural (anatomical) explanations of disease were considered secondary to those of function (physiological) 3 Historical Study of the Human Body1 Ancient Egyptian physicians do not appear to have used anatomy to inform their theory of disease Greek doctors were not especially interested in anatomy – Dissection of human bodies was forbidden – Funeral practices centered on cremation Few opportunities arose for examination of the internal structures of humans 4 Historical Study of the Human Body1 • 300 B.C.—City of Alexandria permits dissection of bodies of criminals, alive or dead – Designed to horrify as much as instruct • 129 A.D.—Galen, physician to the gladiators – Wrote treatises devoted to human anatomy and deplored the laws that forbade dissection – Dissected animals – May have taken advantage of the gaping wounds of gladiators – Created medical texts that were used for more than a thousand years 5 Historical Study of the Human Body1 • Throughout the 13th to 16th century, dissection became increasingly permitted by law in many European countries – Determining cause of death in cases of murder and other situations – Usually permissible to dissect criminals or other low status individuals • The rise of secular universities – Christian tradition linked the body to sin, as did learning about its inner workings (could jeopardize salvation) 6 Historical Study of the Human Body1 • Legal dissections were ritualized and infrequent • Professor sat high above the scene, reading from a Latin edition of Galen • Demonstrators were often non-literate barbers who dissected in conjunction with the lesson • Differences between the cadaver and Galen’s text were “imperfections” of the criminal mortal 7 Why were barbers demonstrating the dissections?1,3 – Surgeons were part of the barber class in the 15th and 16th century – Derived income from shaving, cutting hair, pulling teeth, and bloodletting • Accidents were incidental • Had the tools to cut – Often illiterate and inferior in status to physicians • Humble origins, were not permitted into learned placed (medical colleges) • Learned through apprenticeships until able to formally organize/join “academic surgeons” of the long robe 8 History of the Barber Pole3 • Staff—for patient’s to grip, causing veins to stand out sharply off arm • Copious supply of linen bandages to clean up blood • After the operation, bandages would be hung on staff, sometimes for advertisement • Barbers used to advertise their services by displaying large jugs of blood in the window4 • 1307-law passed in London— ”no barber shall be so rash or bold as to exhibit blood in their window” • The brass pommel at the end represents the containers in which they used to store the blood 9 Historical Study of the Human Body1 • Renaissance art contributed to anatomy and artists conducted dissections • Why didn’t physicians value anatomical study? – Anatomical structural problems (except fractures and dislocations) were impossible to fix 10 Historical Study of the Human Body1 • 16th and 17th century—anatomists focus on discovery and artistic portrayal of the human form • Not until early 17th century did scientists begin to relate structure to disease—field of physiology found application for new anatomical research • By the 18th century dissections become more respectable—new philosophy of knowledge emphasizes wisdom coming from observation through the senses 11 Medical Education in Early America2 • No medical schools in colonial America – Only a few University trained physicians in Europe came to the colonies – They trained other physicians in apprenticeships – No testing or licensing, free to practice with no regulation – Physicians brought their own apprentices to hospitals and encouraged other students to observe treatments – Became so popular that the Philadelphia Hospital began charging students a fee and formalized a training program, others followed 12 Anatomy Goes Medical1 • Beginning of 19th century, dissection becomes essential to medical training • New problem: limited supply of bodies • In urban areas, unclaimed bodies were automatically given to medical educators • But this wasn’t enough . . . 13 Anatomy Goes Medical1 Does anyone know what this is? “Resurrection Man” • New occupation – AKA “body snatchers” – Retrieved fresh corpses to use as cadavers from cemeteries – Or to avoid middle man costs, students learned to harvest corpses themselves • Wealthy could afford one of these – “mortsafes” – Or hired sentries to guard family plots 14 Anatomy Goes Medical1 • Where medical schools operated in close proximity to graveyards, the human body trade was ruthlessly competitive • The inevitable happened: murder for the sale of corpses • Unknown numbers of disadvantaged people may have been killed to this end • 1823: William Burke and William Hare found guilty of murdering at least 16 people and selling the corpses to Robert Knox, anatomist at leading medical school in Edinburgh, Scotland 15 Chris Baker5 • Officially the janitor • Unofficially the MCV campus resurrection man, aka “anatomical man” • Procured bodies and cleaned bones • “ruled the dissection room and possessed considerable knowledge of human anatomy”6 • Took students to local cemeteries to rob graves • Dr. Bosher, anatomy professor condoned this activity • Lived in the Egyptian building 16 Medical Education in Early America2 • Flexner Report and Medical School Reforms – Funded by the Carnegie foundation in 1905 – Examined medical school entrance requirements, size and training of the faculty, endowment funds, quality of laboratories, and the relationships between medical schools and hospitals – Searing indictment of most medical schools of the time • “disgrace” “plague spot” • Recommended corrective measures • Schools closed, others consolidated 17 Medical Education in Early America2 • Flexner Report and Medical School Reforms – Dartmouth, Yale , and Columbia improved quality of their programs – Harvard and Johns Hopkins recognized as excellent – Increased leverage of medical reformers • • • • Licensing legislation was pursued more vigorously Medical training became more standardized Quality of laboratories and other facilities established Most important: financial support for medical school from foundations and wealthy individuals 18 Transition to Academic Medical/Health Centers2 • Federal research grants of the 1950s and 60s encouraged research-oriented medical schools and their teaching hospitals to become the country’s centers of scientific and technologic advances • Other professional health care programs were added—nursing, pharmacy, dentistry, and allied health • The research agenda continues and new ethical issues arise . . . 19 Distrust of Doctors and Hospitals 20 References 1. Sultz, H. A., & Young, K. M. (2006). Health care, USA: Understanding its organization and delivery. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2. Duffin, J. (2010). History of medicine: a scandalously short introduction. University of Toronto Press. 3. http://www.tn.gov/regboards/barber/bpolehis.shtml 4. http://www.swide.com/art-culture/history/barber-shoppole-history/2013/09/29 5. http://wp.vcu.edu/richmondcemeteries/wpcontent/uploads/sites/1876/2012/09/Schmitz_ChrisBaker. pdf 6. http://www.virginiamemory.com/blogs/out_of_the_box/2 010/10/27/chris-baker-cheerful-among-corpses/ 7. http://www.reddit.com/r/HistoryPorn/comments/22uek4 /uva_school_of_medicine_cadaver_society_3rd_club/ 21