Chapter 5: Atomic Structure Early Models of Atoms

advertisement

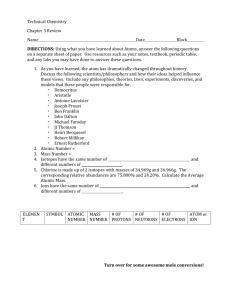

Chapter 5: Atomic Structure Early Models of Atoms • Democritus (460-400B.C.) first suggested the existence of these particles, which he called “atoms” for the Greek word for “uncuttable”. They lacked experimental support due to the lack of scientific testing at the time. • John Dalton (1766-1844) performed experiments to study the ratios in which elements combine in chemical reactions. Formulate hypotheses and theories to explain his observations, which became Dalton’s Atomic Theory. – All elements are composed of tiny indivisible particles called atoms. – Atoms of the same element are identical. The atoms of any one element are different from those of any other element. – Atoms of different elements can physically mix together or combine in simple, whole number ratios to form compounds. – Chemical reactions occur when atoms are separated, joined or rearranged. Atoms of one element, however, are never changed into atoms of another element as a result of a chemical reaction. Size of an Atom • Imagine grinding a copper coin (penny) into fine dust. Each speck in the small pile of shiny red dust would still have the properties of copper. If by some means you could still make the dust particles smaller you would eventually come upon a particle known as an atom. • An atom is the smallest particle of an element that retains the properties of that element. • A pure copper penny contains about 2.4 X 1022 atoms, compared to the Earth’s population of 6 X 106 people. • If you lined 100,000,000 copper atoms up side by side they would produce a line 1 cm long. Atomic Structure • Atoms are now known to be divisible as they can be broken down to even smaller particles by atom smashers. • J.J. Thomson (1856-1940) discovered electrons using cathode ray tubes. • Robert Millikan (1868-1953) carried out experiments to determine the charge of an electron (-). He also determined the ratio of the charge to the mass of an electron. • In 1886, E. Goldstein observed a cathode ray tube and found rays traveling in the opposite direction to that of the cathode rays. He called these rays canal rays and concluded that they must be positive particles, which are now called protons. • In 1932, James Chadwick confirmed the existence of yet another subatomic particle: the neutron. Neutrons are subatomic particles with no charge but with a mass nearly equal to that of a proton. See simulation • After discovering these subatomic particles, scientists wondered how they were put together. • In 1911, Ernest Rutherford and his coworkers performed the Gold Foil Experiment to further study the phenomenon. Atomic Number • The number of protons in the nucleus of an atom of that element • For an atom with no charge, this is also the number of electrons since the postive charge of the protons cancels the negative charge of the electrons. • Practice problems #7-8 pg 115 Mass Number • Most of the mass of an atom is found in the nucleus so the total number of protons and neutrons equals the mass number. • If you know the atomic umber and mass number you can determine the composition of that atom. • The composition can be represented by the shorthand notation using the element symbol, atomic number and mass number. • For gold, Au is the symbol for the element and the atomic number is subscript and mass number is superscript on the left side. 197 Au 79 • Practice problems 9-11 pg 116 Isotopes • Atoms that have the same number of protons but different number of neutrons. • Affects the shorthand notation of the element. • Practice problems 12-13 on pg 117 Atomic Mass • The average atomic mass for an element due to the different isotopes, the mass of those isotopes and the natural percent abundance. • Add up the different atomic mass of each atom and then divide by the number of atoms. • Or, multiply mass by % and then determine average mass. • Practice problems 14-15 pg 120 and 16-17 pg 121.