Document

advertisement

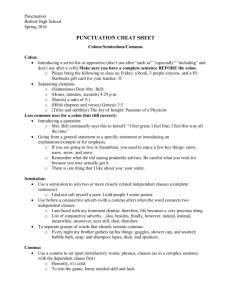

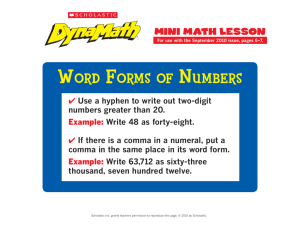

Expository Writing Grammar Points Dr. M. Connor Just hitting the high points The number of possible grammar problems in English writing can seem limitless! I’m going to point out a few very common problems then discuss punctuation. Other problems we’ll face as they come! The sentence fragment As you know, an English sentence must have a subject and a predicate (which contains the verb). If one part of a sentence is missing, you have a sentence fragment. While they can be used sparingly in prose for purposes of style, they are technically incorrect. Examples of sentence fragments Because the sky is blue. – Because the sky is blue what? You need to complete the thought. For example, when I play my piano. – This is a common type of error. In your head it may seem like a complete thought, but in my head I’m saying, when I play the piano what? Revising sentence fragments There are two ways to fix sentence fragments: – by attaching it to a sentence, usually the one that went before it – by adding whatever is necessary to make it a sentence. Method one Music videos began to make their appearance in 1980. Some of them concert performances and some technological innovations. Music videos began to make their appearance in 1980, some of them concert performances and some technological innovations. – Fragment attached to the sentence, separated by a comma. Method two Music videos began to make their appearance in 1980. Some of them concert performances and some technological innovations. Music videos began to make their appearance in 1980. Some of them were concert performances and some were technological innovations. – A verb, were, is added to the fragment, making it a sentence. Run-on sentences These fall into two categories – comma splice – fused sentence Both are always wrong – unlike the sentence fragment that can be used for effect. The Comma splice These are two independent clauses (fancy term for a full sentence) linked together with a comma. Very common when using the word however: – The house looked run-down, however, the inside was in beautiful shape. Use a coordinating conjunction You can separate two independent clauses with a comma only when they are joined by a coordinating conjunction – and – but – or – nor – for – so – yet Examples The mattress caught fire, the flames spread quickly. The mattress caught fire, and the flames spread quickly. Other ways to fix a comma splice Make separate sentences of the two clauses. Insert a semi-colon rather than a comma (more on this later). Make one of the independent clauses into a subordinate clause using a subordinating conjunction. Subordinating conjunctions Examples: – although – after – since – when – that, which, who After the mattress caught fire, the flames spread quickly. The fused sentence This type of error combines two independent clauses with no connecting word or punctuation between them. Dr. Ling is director of the hospital he also maintains a private practice. How to repair a fused sentence It can be corrected in the same way as a comma splice. But grammarians just like to point out that they are two different types of error! Mixed sentences A mixed sentence is a sentence whose parts do not fit together, either in grammar or in meaning. Examples: – The catcher dropped the ball is why the runner is safe. – By seeing the accident made us start wearing seat belts. Beginning one way, ending another Be sure that the parts of your sentences, particularly subjects and predicates, fit together grammatically. – During the worst part of the storm frightened all of us [prepositional phrase used as a subject] – During the worst part of the storm, all of us were frightened. [main clause revised to include a subject] Subjects and predicates fit together Be sure that subjects and predicates of your sentences fit together in meaning. – A prank that irks me is my brother when he jumps out from behind corners. [the prank is not the brother] – A prank that irks me is my brother’s he jumping out from behind corners. [the prank is the jumping] Punctuation Russell Baker, a Pulitzer Prize winning author, wrote an essay on how to punctuate for a series of essays on writing for schools sponsored by the International Paper Company in the 1980s. I’ll be quoting from it here. And adding my own comments as well! Listening to punctuation When you write, you make a sound in the reader’s head. It can be a dull mumble or it can be a joyful noise, a sly whisper, a throb of passion. You need tools! One of the most important tools for making paper speak in your own voice is punctuation. Body language When you speak aloud, you are constantly punctuating. Your listener hears commas, dashes, question marks, exclamation marks as you shout, whisper, pause, wave you arms, roll your eyes, wrinkle your brow. Over 85% of “spoken” communication is non-verbal! Do you see the problem? We need to figure out how to get that 85% of missing body language onto the page! In writing, punctuation plays the part of body language. It helps readers hear you the wat you want to be heard. Lots of scary rules Don’t let the rules scare you. Most of them are common sense. While there are a few “odd” rules, I’ll tell you what they are, so don’t worry. Two basic systems of punctuation The loose, open system which tries to capture the way body language punctuates talk. The tight, closed structural system, which hews closely to the sentence’s grammatical structure. Most of us use a little of both. Punctuation isn’t a “heal-all” Punctuation marks cannot save a sentence that’s badly put together. If you have to struggle over the punctuation, you have probably built a sentence that’s never going to fly, no matter how much you tinker with it. – Throw is away and rebuild a simpler one! Choosing the right tool There are 30 main punctuation marks in English! Most writing gets by on using less than a dozen. I’m going to hit the “highlights” here. The comma [,] This is the most widely used mark of all! It is also the toughest and the most controversial. Baker has seen aging editors almost come to blows over the comma. I have seen grown lawyers screaming curses at one another over the use of the comma! I do not lie! Comma policy Use the comma after a long introductory phrase or clause: – After stealing the crown jewels from the Tower of London, I went home for tea. If the introductory material is short, forget the comma: – After the theft I went home for tea. But, and there’s always a “but”... But use the comma if the sentence would be confusing without it, like this: – The day before I’d robbed the Bank of England. You mean “the day before” to be an introduction, but here it reads like a sentence fragment. You want this: – The day before, I’d robbed the Bank of England. Series Use a comma to separate elements in a series. – I robbed the Denver Mint, the Bank of England, the Tower of London and my piggy bank. Notice there is no comma before and in the series. This is common style nowadays, but some publishers use a comma there as well. Your choice. When using a conjunction As noted earlier, you use a comma when separating independent clauses that are joined by a conjunction like and, but, for, or, nor, because or so: – I shall return the crown jewels, for they are too heavy to wear. Mildly parenthetical word grouping Use a comma to set off a mildly parenthetical word grouping that isn’t essential to the meaning of the sentence: – Boys, who have always interested me, usually differ from girls. Notice how we could lose the part in blue without effecting the meaning of the sentence. Another “but” Do not use commas if the word grouping is essential to the meaning of the sentence: – Boys who interest me know how to tango. See the difference between this and the slide before? Use in direct address Use a comma in direct address: – Your majesty, please hand over the crown. – Officer, I swear I wasn’t speeding! – Dear sweet Dr. Connor, I haven’t done my homework. Between proper names and titles Always use a comma between proper names and titles: – Montague Sneed, Director of Scotland Yard, was assigned to the case. – George W. Bush, President of the United States, is fighting for reelection. – Marguerite Connor, Queen of the Universe, has absolutely no ego problems at all! Geographical address We use a comma to separate elements of geographical address: – Director Sneed comes from Chicago, Illinois, and now lives in London, England. – The address for Fu Jen is 510 Jung Jeng Rd., Hsinchuang, 24205, Taipei County, Taiwan, ROC. Generally speaking… Use a comma where you’d pause briefly in speed. For a long pause of completion of thought, use a period. If you know music, a comma is a onebeat rest, a period is a two-beat rest. Semicolon [;] A more sophisticated mark than the comma, the semicolon separates two independent clauses, but keeps them tightly linked. – I steal crown jewels; she steals hearts. One colleague explained it by saying you use a semicolon when you want to link two sentences like they were cousins. Other semicolon advice I once had an editor who asked me – What does a semicolon sound like? – Like a period, I answered. – Use a period then. Perhaps that’s a bit reductionist, but he had a point. If you’re unsure as to how to use one, don’t! Some semicolon rules Use a semicolon to separate main clauses not joined by a coordinating conjunction. – There are six museums in the city; the largest is the Museum of Fine Arts. Use a semicolon to separate main clauses joined by a conjunctive adverb. – The reporters waited for an explanation of the policy change; indeed, they felt they were entitled to it. Conjunctive adverbs Accordingly also anyway besides certainly consequently finally further furthermore hence however incidentally meanwhile Moreover namely nevertheless next nonetheless now otherwise similarly still then thereafter thus undoubtedly On with the ; rules Use a semicolon to separate main clauses if they are very long or complex or if they contain commas, even when they are joined by a coordinating conjunction. – The literacy rate in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore is about 50%; but in Cambodia and Laos the rate is 70% and 80% respectively. – The announcement that classes were cancelled were posted all over campus; yet dozens of students showed up anyway. Dash [--] and Parenthesis [( )] Warning! Use sparingly. The dash SHOUTS. Parenthesis whisper. Shout too often and people stop listening (think of when your dad starts). Whisper too much and people become suspicious of you. The Dash The dash creates a dramatic pause to prepare for an expression needing strong emphasis. – I’ll marry you--if you’ll rob the Post Office with me. – Care, tenderness, a sense of humor--Ryan possessed all of these. – Some of the largest animals--elephants, rhinos, and blue whales--are in danger of extinction. Parenthesis Parenthesis help you pause quietly to drop in some chatty information not vital to your story. – Despite Betty’s daring spirit (“I love robbing your piggy bank,” she often said), she was a terrible dancer. – William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) was not only a poet but also a playwright and essayist, and some say, a seer into the future. Quotation marks [“ ”] These tell the reader you’re reciting the exact words someone said or wrote: – Betty said, “I can’t tango.” – OR – “I can’t tango,” Betty said. Notice the comma comes before the quote marks in the first example, but comes before them in the second. Not logical? Never mind, do it that way anyway. More uses We also use quotation marks around the titles of a short story, poem, song or book chapter. In other words, part of a whole work, which we would italicize. – “My Happy Ending” is a great song on Avril Levigne’s album Under My Skin. – “The Second Coming” is from W.B. Yeats’s volume Michael Robartes And The Dancer, 1921. The colon [:] A colon is a tip-off to get ready for what’s next: a list, a long quotation, or an explanation. The message is: “Stay on your toes; it’s coming at you!” The apostrophe [’] This causes a big headache when it comes to possessive nouns. If the noun is singular, add ’s – I hated Betty’s tango. If the noun is plural, simply add an apostrophe after the s. – Those are the girls’ coats. Now for the headache part The same applies for singular nouns ending in “s” like Dickens and words ending in “z” like Lopez – This is Dickens’s best book. – This is Mr. Lopez’s car. And now in the plural, add “es’ ”: – This is the Dickenses’ cottage. – This is the Lopezes’ boat. Possessive pronouns Possessive pronoun his, hers and its have no apostrophe. If you write it’s, you are saying it is. Contractions The other use for apostrophes is in contractions. Can not can’t and so on. Ending punctuation [. ? !] Remember to end your sentences with a period if they need one. Questions, of course, need to take a question mark. You can also use an exclamation point, but do you have to? Too many times they make you sound breathless and silly. Use your words to generate excitement, not a bunch of !!!!