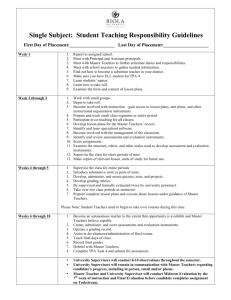

Borraz - Berkeley 2012 - Comparative Risk Regulation Workshop

advertisement

The state can’t fail! Accounting for the limited diffusion of risk-based approaches in France Olivier Borraz CNRS research professor The problem • Limited diffusion of risk-based instruments in French political and administrative institutions. • In contrast with: • Anglo-Saxon countries where risk-based approaches are applied across policy domains; • international norms of “good governance” and “better regulation” that promote risk-based regulation as a rational and objective method of policymaking. 2 Hypothesis • The adoption of new ideas in policymaking implies some form of compliance with entrenched ideas of what is a legitimate or just decision. • Hypothesis: A set of institutional, legal, ideological and political features of the French state work against the adoption of risk-based instruments by blocking them, by ignoring them or by imposing adjustments that limit their impact: 1. The promise of (total) protection. 2. The priority given to maintaining “public order”. 3. The embodiment of the “general interest” by top civil servants. 4. The Republican principle of “equal treatment” by the law. 3 The role of the state … and its limits. • All 4 features embody strong conceptions of the role of the state. • In particular the notion that the state is distinct from society and has: • • • the authority and legitimacy to impose decisions in the general interest of the nation; the obligation to protect society from any danger; the mission to uphold the principle of equality. • Is there a limit to the role of the state? • • Judges decide when the equilibrium between the general interest and individual liberties tilts too far in the direction of the former (rule of proportionality). But their decision ultimately rests on an appraisal that is inherently value-based. • HowSAFE is premised on the idea that the adoption of risk-based instruments makes (or seeks to make) these limits both visible and legitimate, thus making accountability for failure more acceptable. • • In Anglo-Saxon countries, risk-based approaches comply with the idea that the state should have a limited role and that the general will is nothing more than the sum of individual liberties. In France, to suggest that there are limits to the role of the state and, more importantly, that the state can in some circumstances fail, is simply unacceptable. 11/12/12 The state can't fail! 4 1. The promise to protect • Safety is a regalian function of the state. • A renewed interest in this function in 1980s. • During this period, a series of crises and scandals were blamed on the state for failing to prevent negative events from occurring, or mismanaging their occurrence: • • • • • • • • Tainted blood scandal (1991-1999) Chernobyl cloud in 1986 BSE (1996 / 2000) GM controversy (1996-) Asbestos (1994-) Heat wave (2003) Mediator (2010-) Etc. 5 Major health crises and scandals • Other countries underwent similar crises, but in France this led to a renewed emphasis on the role of the state (and the state alone) in preventing such events. State is systemically blamed for failing to act appropriately. This leads to reforms that reinforce the capacity of the state to protect its population against a wide range of hazards. Safety is presented as non-negotiable. These reforms inevitably lead to failures. Further reforms are necessary. • The objective of these reforms is to maintain the centrality of the state as an agent of regulation and control. 6 Examples • Why was the 2003 heatwave a political crisis? • Comparable numbers of people died throughout Europe. • The 15 000 deaths were attributed to a failure by the state to warn the population, due to a lack of information. • Other causes of deaths were overlooked. The state had once again failed, even as it had just finished reforming its health safety system. • H5N1 preparedness plans are organized around the role of the state, with very little room for the intervention of other civil society actors. 7 Risk vs. the promise to protect • Risk-based instruments present a challenge: they suggest the possibility of failure. • Risk-based instruments were introduced in domains destabilized by crises and scandals. • to comply with international standards; • to demonstrate a transformation in policymaking procedures towards more objectivity, robustness and transparency. • But they were limited to risk assessment and did not extend to risk management (rule setting, enforcement and control). • They were not applied to other policy domains, in which the possibility of failure is still denied. 8 2. Public order • Public order (p.o.) has no legal or constitutional backing, yet constitutes a priority for civil servants. • For administrative and constitutional courts, p.o. refers to: • • • • • “good order”, safety (vs. disorders), security (vs. accidents), public hygiene (vs. health hazards) public tranquillity (vs. nuisances). • Laws and their implementation must preserve p.o. • Civil servants bestowed with powers of administrative police have the responsibility to avoid disturbances to p.o. when implementing public regulations. 9 Example • Food safety inspections must, according to the EU hygiene package, rely on a risk-based method in order to determine which firms or farms should be inspected (and how many times). Their results should be made public. • This presents two threats. • Local inspectorates would need to follow an objective method limiting their capacity to decide who to control. • The results could reveal cases of non-compliance with regulation. • Risk-based instruments were thus adopted and then immediately adjusted: • to offer local state services the possibility to introduce “fudge factors” in the official formula to account for local specificities in determining who (and who not) to control and with what frequency; • their results remained confined within their administration, and neither made public nor transferred to risk-assessment agencies. 10 Risk vs. public order • Maintaining p.o. rests on discretion and striking a balance between competing interests in the implementation and control of regulation: this is not immediately compatible with a more formalized approach. • Introducing risk-based instruments would: • make the compromises visible, thus weakening the position of civil servants and causing potential disturbances for p.o.; • or trigger reactions from private actors protesting against measures that are not adapted to their situation, one again threatening to disturb p.o. 11 3. General interest • General interest (g.i.) suggests the existence of a general will, distinct and separate from the sum of particular interests. • The legislative process guarantees that laws are voted by a sovereign assembly acting on behalf of the Nation. • Administrative and constitutional courts refer to g.i. when judging decisions impinging on individual rights. • All civil servants are expected to act on behalf of g.i. • But in a country in which power lies in the hands of the executive branch, top civil servants are expected to embody and defend the g.i. • S. Breyer suggested that due to their training and ethical values, this technocratic elite provided all the guarantees for decisions based on sound evidence and a sense of g.i., shielded from political intervention and particular interests. • Hence they should be expected to adopt risk-based instruments that provide robust evidence to make the best decisions. 12 Example • In the discussions leading to the 1998 law on health safety and the creation of agencies, two sides were opposed: • proponents of an “American-style” regulation regime pushed for independent agencies in charge of risk assessment (RA) and risk management (RM); • ministries of agriculture and finance invoked the NRC “red book” to justify delegating RA to agencies, while RM should remain in their hands. • Risk-based instruments were introduced in the agencies to provide robust and objective evidence, but did not extend to decision-making, which requires balancing other elements and considerations to arrive to a decision in the g.i. • Ministries monitor the border between RA and RM and refuse any formalization of RM within the decision-making process, as this would infringe on their capacity to determine the g.i. 13 Risk vs. general interest • • Risk-based instruments, like any method of quantification, entail a shift from individual judgment (based on personal training, experience and ethics), to a procedural approach (in which the validity of the evidence produced derives from compliance with rules and protocols). In the past, instruments of quantification were used to prepare decisions: • • • • • CBA in the construction of roads, dams and bridges; Health economics to rationalize health expenditures. But in these cases, formal instruments were destined to reduce political interferences in infrastructure decisions or the influence of the medical profession in health policies. They were introduced by civil servants in a dominated position who saw in the introduction of an “objective” method of quantification a way to gain a dominant position in the decision-making process. Hence one could expect risk-based instruments to be introduced in policy domains in which civil servants are confronted with powerful actors or perceive threats or challenges to their authority. But in all most cases, they will oppose the introduction of instruments that could weaken their capacity to determine the g.i.: by constraining their judgment; by introducing openness and transparency, or by replacing informal expertise by formalized procedures. 14 4. Equal treatment • The principle that all citizens must be treated equally by the law is enshrined in the constitution. • This principle is not absolute, exceptions are possible, for instance in the name of the g.i. • But it remains a key value of French civil servants and is present throughout the policymaking process. • Equal treatment implies that individuals or groups should not be treated differently on account of their ethnic origins, religion, gender, social status ... 15 Examples • In the 1980s during the Aids epidemic, health policies consistently refused to single out specific groups at risk and diffused only general messages of prevention. • During the 2010 H1N1 pandemic, the minister of health had to decide on a vaccination campaign: • she could have limited vaccination to a fraction of the population, sufficient to provide herd immunity; • instead she opted for a general campaign, on the argument that this was “an ethical and republican decision”: she had grounds neither to determine which part of the population should be vaccinated, nor to refuse to all those who asked for protection the benefit of the vaccine. • A later parliamentary report stated that this was the only possible solution, since “the French people, deeply attached to the principle of equality, could only agree with the decision” to offer everyone the possibility of getting vaccinated. 16 Risk vs. equal rights • Risk-based instruments can contribute to the identification of groups that are either “at risk” or “risk factors” – thus requiring special measures. • This is not possible in France, as it could lead to unequal treatment or involve a risk of stigmatization. • Often, it is not even feasible given the lack the data due to restrictions on census and quantitative surveys. • When unequal treatment does in fact exist, it is not publicly acknowledged and remains hidden. • The only “acceptable” exceptions are justified by age or gender. 17 5. Accounting for failure • Given the limited adoption of risk-based instruments, how are the inevitable limits of governance dealt with in these circumstances? • Strong reliance on secrecy and opacity. • Holding individual state officials accountable for failures that have become visible. • Installing early warning systems. • Investing in crisis management. 18 Concluding remarks • The adoption of risk-based instruments is a marker of how states account for the limits of their action (in terms of capacity). • The French state has difficulties acknowledging the possibility of failure, as this would hurt its legitimacy. • It also provides an indication as to where they set the limits (boundaries) of their action. • The limits of the French state are not always clear and there is no intention to make those limits clearer: this would imply acknowledging that civil society actors have an autonomous capacity to organize and regulate their activities. 19