Management Accounting - California State University, Sacramento

advertisement

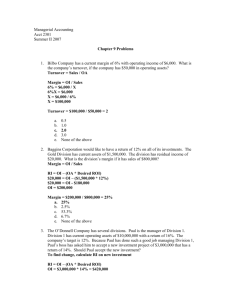

Management Accounting: A Road of Discovery Management Accounting: A Road of Discovery James T. Mackey Michael F. Thomas Presentations by: Roderick S. Barclay Texas A&M University - Commerce James T. Mackey California State University - Sacramento © 2000 South-Western College Publishing Chapter 8 Will our people do this? Motivation and control through accounting information Key Learning Objectives 1. Describe the motivational relationship between planning, control, and evaluation. 3. Explain three motivational problems with using accounting information in performance evaluation. 5. Compute ROI and residual income, and explain their motivational implications. 7. [Appendix A] Demonstrate how service department and common cost allocations can support cost control. 2. Discuss the evolution from clan control to accounting control and accounting’s control hierarchy. 4. Prepare a segmented income statement and explain its usefulness in evaluating segments and managers. 6. Summarize five ethical concerns with management’s use of accounting control measures. Part I The Meaning of Control Control Means: Getting people to do what you want. Or Getting people to always act to maintain or improve company value. Or Getting people to always act according to established rules or procedures. For management purposes we wish to make managers make ‘good decisions and exercise good judgment’. Good judgment requires motivation and direction. A Personal Example Is your grade in this course a good performance measure to control your behavior? If the objective of a college education is to create long-term value, does increasing your GPA reflect an increase in your long-term value? Does the calculation and components of the grade direct you to do long-term value adding actions? If the grade is used to evaluate your performance, do you have sufficient control over the factors that determine your grade? Do you have control over the activities for which you are held responsible? The Motivational Cycle Goal Congruence (employees do what we want) Responsibility Based on Controllability (employees given the power to decide) Reward System (offer adequate rewards) Performance Measures (measure the right things, the right way) About The Control Environment Planning often requires guesswork from employees about costs versus revenues. Management prefers hard data for evaluation. Employee participation and their beliefs about legitimacy are necessary. Management needs to encourage building in a cushion or slack. Remember ‘What gets measured gets done’. Understand the conflict between better decisions or better control. Part II Many Types of Controls How Much Accounting Control Do We Need? Control System Role of accounting information in control Clan control Secondary (informal, infrequent direct observation is primary source of control) Market control Secondary (primary source is external — police ticket) Bureaucratic rules (centralized) Shared (frequent direct observation or accounting system when direct observation is not practical Bureaucratic rules (decentralized) Primary (accounting system measures the outputs from the black box) Types of Controls Control can be achieved through any combination of: Clan Control — We have the same values or culture. Bureaucratic Control — We follow the same rules. Accounting Control — We follow management by the numbers. Market Control — We follow what the market values most. Most companies use a mix of controls subject to the costs and benefits of their situation (and the corporate culture). Centralized vs. Decentralized Controls Centralized management — Higher level corporate management makes more decisions. Decentralized management — Managers at lower levels make more decisions. If accounting measures accurately measure value, then centralized ‘Management by the Numbers’ is more efficient. Responsibility Centers used in Accounting Control Systems Cost center Profit center Investment center Its budget covers only the costs incurred. Cost center activities create costs such as in a production department. Cost variances have been the primary accounting control measure. Its budget includes revenues and costs. Profit centers normally are product lines or sales territories. A profit center’s activities create revenues and incur costs. Sales and cost variances have been the primary accounting control measures. Its budget involves investment and profit activities. Its activities involve asset purchases that are used to generate profits, (e.g., divisions or companies). Primary accounting measures include sales and cost variances, and expression of profit in relation to investment, (e.g., ROI, residual income, and economic value added). Limitations for ‘Management by the Numbers’ or Accounting Control Does the accounting measure reflect company value? Does the accounting measure reflect the results of activities which the managers are responsible for and which they can control? Do the accounting measures direct managers to actions that improve value? Part III Segmented Income Statements Segment Profitability Statement Sales - Variable product expenses = Contribution margin from product sales - Controllable fixed costs = Segment contribution margin - Common (allocated) costs = Segment profit margin Evaluation of Managers and Divisions These reports are designed to identify the costs and revenues influenced or controlled by manager’s activities and those due to a business segment. Review and analyze Exhibit 8-5, p. 273. Note that this is a full cost report where the segments must equal the company total. Hidden in these numbers are: The costs controllable by the segment manager. The costs not controllable by the segment manager but only existing for this segment. Common fixed costs allocated to the segment but not related to segment activity. Assigning Costs by ‘Ability to Bear’ or Sales Revenue Common costs are costs necessary for the company to exist but cannot be related to a particular segment. Since full costing says all our costs must be recovered, the common costs are assigned to each segment by their relative sales activity. Remember, this isn’t GAAP and will vary in practice. Review Exhibit 8-5, p. 273 again. If we sell one more standard home, why will the increase in net income exceed $8,552? Why not? If the standard home line is dropped, will the reduction in total net income be $855,167? Why not? Segment Margin Statements Common costs are not assigned to segments or product lines. Common fixed costs are taken out of the overhead costs. Review and analyze Exhibit 8-8, p. 280. If one more standard house were sold, how would the total company profit change? If the company dropped the standard home line, how would the total company profit change? Controllable Segment Margin Statements For evaluation and motivation, fixed costs not controllable by the segment managers should not be part of the bonus system. Review and analyze Exhibit 8-9, p. 281. If a manager’s performance and bonus are based on the controllable segment margin, explain how managers can increase their bonus and company value at the same time. Assume you are the manager of the standard homes segment, what actions does this statement suggest you can take to both improve your bonus and increase company value? Limitations of Segment Reports Common costs are difficult to allocate based upon cause and effect. Segments often influence each other’s performance. All accounting measures ae subject to errors and may be estimates. If dropping the Custom Division also reduced the sales of the Standard homes division by 10%, what would be the decrease in the total Net Income? Refer back to Exhibit 8-8, p. 280. 10% reduction in Standard Home contribution margin = $200,000 Lost segment margin from Custom homes total decrease for the company = $185,000 = $385,000 Part IV Measures of Relative Profitability Profitability in terms of the money invested is measured by various profit and invested capital calculations. Return on Investment (ROI) Return on Investment = Profit / Investment ROI = Sales Margin x Sales Turnover Sales Margin = Profit / Sales Sales Turnover = Sales / Investment • The Sales Margin measures the relative profit on each sales dollar. Increasing the sales margin by increasing the profit on sales will improve the ROI. • The Sales Turnover ratio examines how efficiently the investment in assets is used to generate sales. Increasing sales while maintaining the same level of investment or decreasing the level of investment will increase the ROI. In practice there is considerable variation in the items that are included in each category depending on the firm’s objectives. An Illustration Division A Division B $10,000,000 $2,000,000 8,000,000 500,000 1,000,000 500,000 Operating income $ 1,500,000 $ 500,000 Capital Invested $10,000,000 $3,000,000 Sales Less: Operating expenses R&D For A: For B: ROI = $1,500,000 / $10,000,000 = 15% ROI = $ 500,000 / $3,000,000 = 16.7% For A: For B: Sales Margin = $1,500,000 / $10,000,000 = 15% Sales Margin = $500,000 / $2,000,000 = 25% For A: For B: Turnover Ratio = $10,000,000 / $10,000,000 = 1.0 Turnover Ratio = $2,000,000 / $3,000,000 = 0.67 Part V Residual Income (RI) and The Cost of Capital (COC) Definitions The residual income measures the profits returned after a ‘Cost of Capital’ (COC) charge is recovered from the segment or division. Residual income (RI) is simply the operating profit less the COC. An Illustration For Divisions A & B with a 12% COC, the Residual Income is: A $1,500,000 Operating Income Less: 12% x $10,000,000 $1,200,000 12% x $3,000,000 Residual Income $ 300,000 B $500,000 $360,000 $140,000 Cost of Capital Employed: This is the rate of return required by the company multiplied by the capital employed. Arguments surround how this capital charge should be calculated. Some authors suggest that it should reflect the unique risk for each segment. Riskier segments should have a higher COC, safer segments less. Others argue that the cost of capital should reflect the value of alternative uses for the invested capital, or the firm’s cost of borrowing money. ROI versus RI ROI measures the average return for dollars invested. RI measures net excess (shortfall) over the cost of capital required. ROI versus RI measures the return over the life of the product. Review Exhibit 8-13, p. 289 for an illustration of a multi-year investment. Accounting Performance Measures Economic value added (EVA ) Residual income Investment x (ROI – Cost of capital) Return on investment (ROI) (Segment profit ratio x Asset turnover ratio) Segment profit ratio Asset turnover ratio (Segment profit / Sales) (Sales / Segment assets) Sales variances Cost variances Cash budgets Capital budgets (price & volume) (price & usage) (working capital) Implementation audits Economic Value Added — EVA The overall calculation is roughly the same as RI. However, the costs and revenues used may change from company to company. The idea behind changes to the GAAP numbers is that they do not always reflect changes in value. Adjustments are made to the accounting numbers so that changes in value are captured. For each company any one of many adjustments can be made to better measure value. While the measurements are debated, EVA has become extremely popular as an organizational performance measure. Adjustments to Reflect Economic Value EVA theory states that research and development is an asset and contributes to future value. It is not a current expense for the EVA calculation. Thus, R&D expenses are subtracted from operating income to calculate the EVA for each division. Division B is much riskier than Division A, therefore the COC for A is 10% and for B it is 15%. Note: There is approximately 160 adjustments that are possible for us to make to GAAP based accounting numbers to truly illustrate the economic value of a company. Divisions A and B Revisited A B Adjusted Operating Income $1,500,000 + $500,000 $2,000,000 $ 500,000 + $500,000 $1,000,000 Less Adjusted COC 10% x $10,000,000 15% x $ 3,000,000 $ 450,000 EVA 1,000,000 $1,000,000 $ 550,000 Part V Do Our Accounting Systems Encourage Good Judgment? Non-Financial Measures of Value Financial measures are ‘lag’ indicators of value. Non-financial measures of value may predict value changes sooner than financial measures. What Gets Measure Gets Done, But If We Measure the Wrong things The Wrong Things Will be Done And The Wrong things May be Done Very Well