Latin American Revolution Teacher Notes

advertisement

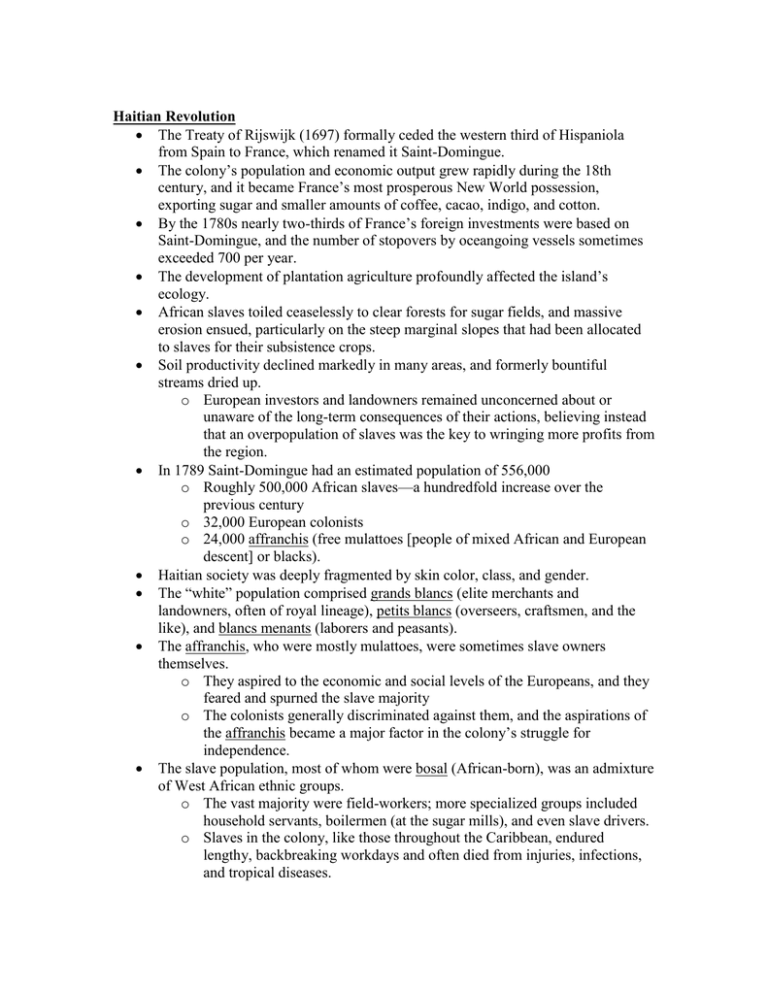

Haitian Revolution The Treaty of Rijswijk (1697) formally ceded the western third of Hispaniola from Spain to France, which renamed it Saint-Domingue. The colony’s population and economic output grew rapidly during the 18th century, and it became France’s most prosperous New World possession, exporting sugar and smaller amounts of coffee, cacao, indigo, and cotton. By the 1780s nearly two-thirds of France’s foreign investments were based on Saint-Domingue, and the number of stopovers by oceangoing vessels sometimes exceeded 700 per year. The development of plantation agriculture profoundly affected the island’s ecology. African slaves toiled ceaselessly to clear forests for sugar fields, and massive erosion ensued, particularly on the steep marginal slopes that had been allocated to slaves for their subsistence crops. Soil productivity declined markedly in many areas, and formerly bountiful streams dried up. o European investors and landowners remained unconcerned about or unaware of the long-term consequences of their actions, believing instead that an overpopulation of slaves was the key to wringing more profits from the region. In 1789 Saint-Domingue had an estimated population of 556,000 o Roughly 500,000 African slaves—a hundredfold increase over the previous century o 32,000 European colonists o 24,000 affranchis (free mulattoes [people of mixed African and European descent] or blacks). Haitian society was deeply fragmented by skin color, class, and gender. The “white” population comprised grands blancs (elite merchants and landowners, often of royal lineage), petits blancs (overseers, craftsmen, and the like), and blancs menants (laborers and peasants). The affranchis, who were mostly mulattoes, were sometimes slave owners themselves. o They aspired to the economic and social levels of the Europeans, and they feared and spurned the slave majority o The colonists generally discriminated against them, and the aspirations of the affranchis became a major factor in the colony’s struggle for independence. The slave population, most of whom were bosal (African-born), was an admixture of West African ethnic groups. o The vast majority were field-workers; more specialized groups included household servants, boilermen (at the sugar mills), and even slave drivers. o Slaves in the colony, like those throughout the Caribbean, endured lengthy, backbreaking workdays and often died from injuries, infections, and tropical diseases. o Malnutrition and starvation also were common because plantation owners failed to plan adequately for food shortages, drought, and natural disasters, and slaves were allowed scarce time to tend their own crops. o Some slaves managed to escape into the mountainous interior, where they became known as Maroons and fought guerrilla battles against colonial militia. o Large numbers of slaves, Maroons, and affranchis found solace in Vodou (Voodoo), a syncretic religion incorporating West African belief systems. o Others became fervent adherents of Roman Catholicism, and many began to practice both religions. The revolution was actually a series of conflicts during the period 1791–1804 that involved shifting alliances of Haitian slaves, affranchis, mulattoes, and colonists, as well as British and French army troops. Several factors precipitated the event, including the affranchis’ frustrations with a racist society, the French Revolution, nationalistic rhetoric expressed during Vodou ceremonies, the continuing brutality of slave owners, and wars between European powers. Vincent Ogé, a mulatto who had lobbied the Parisian assembly for colonial reforms, led an uprising in late 1790 but was captured, tortured, and executed. In May 1791 the French revolutionary government granted citizenship to the wealthier affranchis, but Haiti’s European population refused to comply with the law. Within two months isolated fighting broke out between Europeans and affranchis, and in August thousands of slaves rose in rebellion. The Europeans attempted to appease the mulattoes in order to quell the slave revolt, and the French assembly granted citizenship to all affranchis in April 1792. The country was torn by rival factions, some of which were supported by Spanish colonists in Santo Domingo (on the eastern side of the island, which later became the Dominican Republic) or by British troops from Jamaica. In 1793 Léger Félicité Sonthonax, who was sent from France to maintain order, offered freedom to slaves who joined his army; he soon abolished slavery altogether, and the following year the French government confirmed his decision. Spain ceded the rest of the island to France in the Treaty of Basel (1795), but war in Europe precluded the actual transfer of possession. In the late 1790s, Toussaint L’Ouverture, a military leader and former slave, gained control of several areas and earned the initial support of French agents. He gave nominal allegiance to France while pursuing his own political and military designs, which included negotiating with the British, and in May 1801 he had himself named “governor-general for life.” Napoléon Bonaparte wishing to maintain control of the island, attempted to restore the old regime (and European rule) by sending his brother-in-law, Gen. Charles Leclerc, with an experienced force from Saint-Domingue that included several exiled mulatto officers. Toussaint struggled for several months against Leclerc’s forces before agreeing to an armistice in May 1802; however, the French broke the agreement and imprisoned him in France. He died on April 7, 1803. Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henry Christophe led a black army against the French in 1802, following evidence that Napoleon intended to restore slavery in Saint-Domingue as he had done in other French possessions. They defeated the French commander and a large part of his army, and in November 1803 the viscount de Rochambeau surrendered the remnant of the expedition. The French withdrew from Haiti but maintained a presence in the eastern part of the island until 1809. http://www.britannica.com/place/Haiti/Government-and-society#toc217447 Mexico and South America Napoleon occupying Spain sparked a crisis in the Spanish Empire. Due to Spanish bourbons falling captive to Napoleon in 1807, colonial elites in Buenos Aires (Argentina), Caracas (Venezuela), and Mexico City (Mexico) enjoyed self-rule without an emperor. When Bourbons returned to power in 1814 after Napoleon was crushed, creoles (American-born Spaniards) resented it when Spain reinstated peninsulars (colonial officials born in Spain) and wanted to free themselves of these officials In Mexico, the Royal Army prevailed as long as there was any hope that the emperor in Madrid could maintain political authority. From 1810 to 1813, two rural priests, Father Miguel Hidalgo and Father Jose Maria Morelos, electrified an insurrection of peasants, Indians, and artisans. They sought an end to abuses by the elite, denounced bad government, and called for redistribution of wealth, return of land to the Indians, and respect for the Virgin of Guadalupe (who later became Mexico’s patron saint). The rebellion nearly choked off Mexico City, the colony’s capital, which horrified peninsulars and creoles alike and led them to support royal armies that eventually crushed the uprising. Even though the military was victorious, Spain’s hold on its colony weakened. Similar to the Creoles of South America, those of Mexico identified themselves more as Mexicans and less as Spanish Americans. So when the Spanish King appeared unable to govern effectively abroad and even within Spain, the colonists considered home rule. A critical factor was the army, which remained faithful to the crown. However, when anarchy seemed to spread through Spain in 1820, Mexican generals (with support of the creoles) proclaimed Mexican independence in 1821. Different from Brazil, Mexican secession did not lead to stability. South America – Other The loosening of Spain’s grip on its colonies was more prolonged and militarized than Britain’s separation from its American colonies. Venezuela’s Simon Bolivar (1783-1830), the son of a merchant-planter family who was educated on Enlightenment texts, dreamed of a land governed by reason. He revered Napoleonic France as a model state built on military heroism and constitutional proclamations. The Argentine leader General Jose de San Martin (1778-1850) agreed. Men like Bolivar, San Martin, and their many generals waged extended wars of independence against Spanish armies and their allies between 1810 and 1824. In present-day Uruguay and Venezuela, the wars left entire provinces depopulated. What started in South America as a political revolution against Spanish colonial authority escalated into a social struggle among Indians, mestizos, slaves, and whites. The militarized populace threatened the planters and merchants o Rural folk battled against aristocratic creoles o Andean Indians fled the mines and occupied great estates o Provinces fought their neighbors Popular armies, having defeated Spanish forces by the 1820s, fought civil wars over the new postcolonial order. New states and collective identities of nationhood now emerged. A narrow elite led these political communities, and their guiding principles were contradictory. Simon Bolivar, urged his followers to become “American”, to overcome their local identities. o He wanted the liberated countries to form a Latin American confederation, urging Peru and Bolivia to join Venezuela, Ecuador, and Colombia in the “Gran Colombia.” o But local identities prevailed, giving way to unstable national republics o Bolivar died surrounded by enemies o San Martin died in exile The real heirs to independence were local military chieftains, who often forged alliances with landowners. The legacy of the Spanish American revolutions was contradictory o The triumph of wealthy elites under a banner of liberty, yet often at the expense of the poorer, ethnic, and mixed populations. Worlds Together, Worlds Apart - Fourth Edition Textbook