Julian Barnes

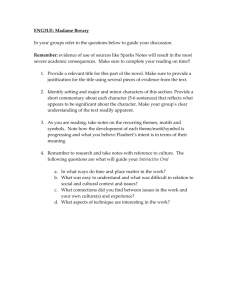

advertisement

Julian Barnes Julian Barnes born in 1946 in Leicester, moved to London 1968: graduates at Oxford (modern languages) works as lexicographer for OED from 1977 on: reviewer and literary editor for New Statesmen, later also The Observer 1980: his first novel, Metroland appears, followed by 21 other books (novels, collections of essays) and translations from French and German married, his wife died in 2008 www.julianbarnes.com Pseudonym: Dan Kavanaugh (detective stories) Metroland (1980) Before She Met Me (1982) Flaubert's Parrot (1984) Staring at the Sun (1986) A History of the World in 10 1/2 Chapters (1989) Talking It Over (1991) The Porcupine (1992) Letters from London 1990-95 (1995) England, England (1998) Love, etc (2000) Something to Declare: French Essays (2002) Arthur and George (2005) Nothing To Be Frightened Of (2008) Pulse (2011) The Sense of an Ending (2011) Man-Booker Prize Through the Window (essays, 2012) Levels of Life (2013) The Man Booker Prize for Fiction 2011 Julian Barnes, The Sense of an Ending Jonathan Cape. This body of work consistently resists categorization, challenging conventional expectations: […] reminiscent of the postmodern texts of Italo Calvino or Milan Kundera in their elegance, sophistication, and linguistic playfulness. Unlike these writers, however, Barnes returns repeatedly, seriously, even obsessively (if often also humorously), to a series of key themes connected to the passions and inconsistencies of the human heart, exploring the unsettling nature of love and (in)fidelity… Cristina Sandru and Sean Matthews, 2002 http://www.contemporarywriters.com/authors/?p=auth1 http://www.eltereader.hu/kiadvanyok/stunned-into-uncertainty-essays-on-julianbarness-fiction/ Although the Lyotardian postmodern “incredulity towards metanarratives” is typical of Barnes, a Barnesian text is never as desperately experimental or as eager to subvert the existing order […] I might call it ‘mild postmodern.’ Ágnes Harasztos the Barnesian character tends to wonder about life instead of living it Dóra Vecsernyés Barnes’s novels draw our attention to trivialities of life, under which he uncovers the most dazzling problems of human existence. Eszter Tory Man no longer the centre of the universe – no centre Rhizome • Structure, sign and play (Jacques Derrida, 1966) ”even today the notion of a structure lacking any center represents the unthinkable itself.” Centerless system (Gilles Deleuze 1925-1995) JEAN-FRANÇOIS LYOTARD THE POSTMODERN CONDITION (1979) Grand narratives “incredulity toward metanarrative” Return of the grand narrative • aftershock of 1960s radicalism, intellectual millenarism (all post-s / the past is dead) • PM: rhetoric of disruption (everything has to be new, break in human experience) heroic age of theory • Incredulity toward metanarratives (Lyotard) progress, enlightenment, Christianity Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880) Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880) • Madame Bovary (1857) • Un Coeur Simple (A Simple Heart) (1877) original title: The Parrot (part of Three Stories) • Félicité: unconditional love (yet fruitless existence) while dying, she imagines the parrot to be an incarnation of the Holy Spirit • sweet, simple, and unrewarded life Flaubert's Parrot (1984) historical fiction – biography – metafiction (prize won as a work of criticism) Geoffrey Braithwaite (elderly doctor, suspiciously deep literary knowledge): obsession with Flaubert structural elements to watch for: repetition variation (= repetition with difference) 3 chronologies (official, personal, literary, later: animal) Bestiary: bear, camel, parrot etc. ‘What happened to the truth is not recorded.’ • Homage to Flaubert (to his person or texts?) • cf: Péter Esterházy’s homage to Géza Ottlik’s text: to celebrate his 70th birthday, in 1982 EP copied the text of School at the Frontier on a sheet of paper • relationship of text and author: ‘Madame Bovary, c’est moi.’ • ‘But if a writer were more like a reader, he’d be a reader, not a writer: it’s as uncomplicated as that’ yet Braithwaite’s obsession with Flaubert is in the context of his wife’s suicide personal grief (narration slowly becoming more personal) stuck in the present, anxiously scanning a fading past ‘Ellen. My wife: someone I feel I understand less well than a foreign writer dead for a hundred years. Is this an aberration, or is it normal? Books say: She did this because. Life says: She did this. Books are where things are explained to you; life is where things aren't. I'm not surprised some people prefer books. Books make sense of life. The only problem is that the lives they make sense of are other people's lives, never your own.’ • narrator’s life mingles with the object • A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters (1989) Sir Walter Raleigh’s monumental The History of the World (1614) • provocative, ironic • Raleigh: comprehensive, providence cf. ‘Historia est magistra vitae’ (Cicero) • Barnes: fragments with motivic connections: arc / boats ”worm’s eye view” • history: necessarily fragmented • cf. David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas (consciously interconnected) A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters • a series of digressions from those events normally considered central to any historical account of the world: an ironic approach to history as a genre (cf. Flaubert’s Parrot) cf. Barthes: ‘The Discourse of History’: traditional historical discourse is ”the fallacy of representation” (ideology); ”establishing positive meaning and filling the vacuum of pure, meaningless series" • Hayden White: history as a narrative • Barnes: "We make up a story to cover the facts we don't know or can't accept; we keep a few facts and spin a new story round them" • Brian Finney: ‘A worm's eye view of history: Julian Barnes's A History of the World in 10 1/2 Chapters’ Papers on Language & Literature. 39.1 (Winter 2003) • Chapter 1: ‘The Stowaway’ Noah’s Ark (biblical re-creation) quasi historical-realistic description of an allegory contrast: anachronistically modern language; deconstructing the myth (ark as death camp) • Chapter 10: ‘The Dream’: contemporary heaven • in between these chapters: no chronological order • Chapter 2 ‘The Visitors’: modern Arab terrorists hijack a pleasure-boat (cf. 1985 Achille Lauro) • Chapter 3 ‘The Wars of Religion’ manuscript of the proceedings of a fictional trial against woodworms in 1520 in France animals: instincts, no freedom, moral causation Chapter 4 ‘The Survivor’ Chernobyl disaster (1986) – dream or mental hospital? ”I’ve started closing my eyes. That’s harder than you think. If you’ve already got your eyes closed in sleep, try closing them again to shut out a nightmare.” Chapter 5 ‘Shipwreck’ 1816: Medusa sinks ‘How do you turn catastrophe into art?’ Théodore Géricault: The Raft of the Medusa (1819) • Chapter 6 ‘The Mountain’ 19th century: an exhibition of Géricault’s painting and a primitive motion picture after death of father daughter to visit a monastery (Noah’s vine) ”Where Amanda discovered in the world divine intent, benevolent order and rigorous justice, her father had seen only chaos, hazard and malice.” • Chapter 7 ‘Three Simple Stories’ survivors of accidents on sea: Titanic, Jonah, Jewish refugees • Chapter 8 ‘Upstream!’ travel in the jungle for a film project (The Mission, 1986), where an actor is drowned in an accident with a raft ‘Parenthesis’ • narrator named Julian Barnes offers a philosophical discussion on love. Cf. El Greco’s The Burial of the Count of Orgaz • Chapter 9 ‘Project Ararat’ story of a fictional astronaut • Chapter 10 ‘The Dream’ • fragments? reader to decide whether interconnected episodes (overarching narrative) or juxtaposed disparate segments • ”The history of the world? Just voices echoing in the dark; images that burn for a few centuries and then fade; stories, old stories that sometimes seem to overlap; strange links, impertinent connections"