Infrastructure Banks Affirmative – MSDI 2012

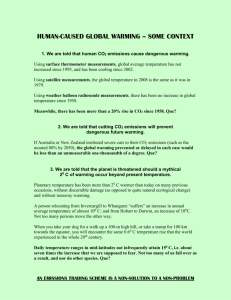

advertisement