Family Dynamics

advertisement

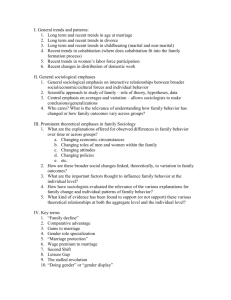

Families and Family Policy in European Context Professor Gray Swicegood Family and Population Studies, CeSO KU Leuven University of Illinois Overview How to consider families: • Family structure: Residential arrangements of population at different points in the life course (e.g. couples, single parent, intergenerational) • Family Dynamics: Transitions between family-defining statuses (union formation, becoming a parent, divorce, death of a spouse) • Family as Experienced: Impact of family structure and dynamics on individual outcomes (e.g. quality of relationships, subjective wellbeing, educational outcomes for children, division of labor in the household) • Family systems (theory) Combines elements of structure and dynamics (perhaps better suited for in depth analysis of a single country or comparing a few) The Life Course Perspective: Connecting micro, meso and macro levels of analysis Family Formation Unions: Cohabition Marriage, Remarriage Parenthood (Fertility) Family Dissolution Separation and Divorce These status transitions create new roles and relations for individuals and are the proximate determinants of changing family structure. The life course perspective clarifies the interrelationship of structure and process. What is “Life Course”? • “As a concept it refers to the age-graded life patterns embedded in social institutions and subject to historical change. The life course consist of interlocking trajectories or pathways across the lifespan that are marked by sequences of social transitions.” Elder’s (1992) definition makes clear the centrality of time to the life course perspective. Time here is viewed in three different dimensions. Age Social Time Historical Time Age can be indexed in terms of chronological passage of time of from some defining event. Social time refers to the socially defined statuses that constituent the life course. Historical time refers to the general social, cultural, technological and economic conditions within which individual life courses are played out. The Life Course Paradigm (Elder, 1992) • Interconnections between fateful historical events and the individual biography. • One important impact of social change can be to widen gaps between generations in terms of shared values and behaviors. • The life course paradigm favors a framing statement that views the socio-cultural environment as the point of departure. ...life course studies place greater emphasis on the social pathways of human lives, their sequence of events, transitions and social roles. Example of Interconnections: Impact of the Depressions Basic Concepts of the Life Course • Cohort: Group of persons who were born at the same historical time and who experience particular social changes within a given culture in the same sequence and at the same age • Transition: Change in roles and statuses that presents a distinct departure from prior roles and statuses • Trajectory: Long-term pattern of stability and change, which usually involves multiple transitions • Life Event: Significant occurrence involving a relatively abrupt change that may produce serious and long-lasting effects • Turning Point: Life event that produces a lasting shift in the life course trajectory Basic Concepts of the Life Course • Transition: Change in roles and statuses that presents a distinct departure from prior roles and statuses – • Life is full of transitions: starting school, entering puberty, leaving school, getting a first job, leaving home, retiring and so on. Trajectory: Long-term pattern of stability and change, which usually involves multiple transitions – Trajectories involve a longer view of long-term patterns of stability and change in a person’s life, involving multiple transitions (Elder & Johnson 2003, George 2003). Key Life Course Events and Status Transitions across Domains. Intimate Relationships/Family • • • • • • • • • Puberty Sexual Activity Leaving Parental Household Parenthood Cohabitation Marriage Divorce Remarriage Widowhood Life course transitions (cont.) • Education • • • • • • • Entries and Exits Preschool/Kindergarten Primary School Secondary School College/Technical/Training Programs Advanced graduate training Later Return to Schooling Life Course Transitions (cont.) Work • • • • • • • First Job First Job Following School Unemployment Underemployment Over Employment Retirement Post-retirement return to work • (careers vs. jobs) Life course transitions: Additional Domains for consideration • Home Ownership • Community/Neighborhood • Avocational Organizations and Networks • Spiritual Domain Mayer: Institutions and the life course. • Institutions can shape life course trajectories is a variety of ways. Institutions are and outcome in part of public policy and in turn shape that policy. • “From the perspective of sociology, then, life courses are considered not as life histories of persons as individuals but as patterned dynamic expressions of social structure. These dynamics operate in populations or subsets of populations, are governed intentionally or unintentionally by institutions, and are the intentional or unintentional outcomes of the behavior of actors. Patterns of life courses are, however, not only products of societies and a part and parcel of social structure but also important mechanisms for generating social structures as the aggregate outcome of individual steps throughout the life course. One transparent example of these processes is evident in the fact that the age and cohort structure of a population is the highly consequential result of a multitude of fertility behaviors and decisions. Likewise, the employment structure is the outcome of a multitude of individual employment trajectories.” • “It is, therefore, the so-called welfare mix (i.e., the relative importance and manner of interconnectedness of economic markets, the family, and the state across historical time and across contemporary societies) that sociologists see as the major determinant of life course patterns (Esping-Andersen, 1999).” Household types across Europe • Households vs. Families (see handout) • The distribution of HH types varies widely. For Nordic countries in the top panel substantial %’s of HH’s are single person under age 65. Substantial number of single person HH headed by older adults are also observed. Greatest contrasts are with the South were especially the first type of single person HH is less likely. • Single parent HH’s are relatively rare but do range widely from 1% in Greece to 7% in Ireland. • Mean HH size over individuals ranges from 2.7 in Denmark to 3.8 in Poland. Single person HH’s are so rare in Denmark that the average HH size across HH’s is only 2 persons. Cohabitation and Marriage across Europe Great variation across the European continent that in some cases dates back centuries. Contemporary differences remain substantial but union formation via cohabitation has been increasing in recent decades even in countries where it was relative rare in the past. Regional differences in union formation and dissolution Marriage rate Age @ marriage Crude divorce rate Net Divorce rate Cohabitation rate FSS Cohabitati on rate ESS In union age 24 Western 0.61 26.4 2.24 9.51 58.1 43.3 70.8 Northern 0.55 27.9 2.36 11.99 81.4 84.4 77.3 Southern 0.69 25.9 0.84 3.77 17.6 21.6 57.4 S.Eastern 0.68 23.6 0.74 3.83 - - 77.3 Central 0.73 22.3 2.93 12.84 19.8 33.6 80.6 See handout for variable description and country specific values. Source: Kalmijn, Matthijs. 2007. “Explaining Cross-National Differences in Marriage Cohabitation and Divorce in Europe, 1990-2000.” Population Studies 61: 243-63. Cohabitation in Europe: A partnership transition? Cohabitation: Cross-national variation in the incidence of, duration in, and route of exit from (A) Marginal (B) Prelude to Marriage Cohabitation “exists as a Cohabitation is not prereproductive prevalent and is phase for adults. discouraged by Unions tend to be public attitudes brief and nonand policies. reproductive, but end in marriage” (C) Stage in Marriage Process (D) Alternative to Singleness (E) Alternative to Marriage Cohabitation “is a discrete Cohabitation component of the “exists as a family system. transitory phase in Adult cohabitation reproduction. “Cohabitation is is prevalent, and for Unions tend to be primarily for brief, longer duration longer, and non-reproductive than in (C). A low children more likely unions that end in proportion lead to to be born into a separation instead marriage; there is cohabitation than of marriage” more exposure to in (B), but with cohabitation during short duration of childhood than in exposure” (C) and for longer duration" (F) Indistinguishable from Marriage “Little social distinction between cohabitation and marriage. Children more likely than in (E) to experience the marriage of their parents, because cohabitation is not seen as an alternative to marriage” Source: Heuveline and Timberlake (2004) Different meanings of cohabitation by country Cohabitation is not prevalent and is likely discouraged by public attitudes and policies. Exists as a pre-reproductive phase for young adults. Brief and nonreproductive unions, but end in marriage. Transitory phase in reproduction. Longer unions and children are more likely to be born into a cohabitation than in (B), but with short duration of exposure. Cohabitation primarily for brief, non-reproductive unions that end in separation instead of marriage. Adulthood cohabitation, and for longer duration than in (C). Low proportion leading to marriage, more exposure to cohabitation during childhood than in (C), and for longer duration. Little social distinction between cohabitation and marriage. Children are more likely than in (E) to experience the marriage of parents, because cohabitation is not seen as an alternative to marriage. Source: Heuveline and Timberlake (2004). Childbearing across Europe. • Dimensions of childbearing. – Transition to parenthood (age at first birth) – Quantum of fertility (transition to higher parities and completed family size) – Aggregate period fertility • Total period fertility rate= average number of children a women would have if she had births at the prevailing age-specific fertility rates. A hypothetical measure for a synthetic cohort. – Family context (union status of parents) Fertility trends from Balter, 2006 European Fertility over Time: Engine of population aging Fertility Trends across Europe • Following a post-WW II baby boom of varying magnitudes most European countries experienced fertility declines from the 1960 onward, with particularly sharp declines for some countries during the 1990’s. • By 2000 almost every country in Europe was below the replacement level fertility of approximately 2.1 • EX. Italy 1.26, Germany 1.38, Belgium 1.67, Netherlands, 1.72, Ireland 1.89, France 1.89 • There had begun already at this time a concern over low fertility. Why? From 1980-20003 the TFR in the EU-25 fell from 1.88 to 1.48. This was lead by very sharp declines in Southern Europe then followed by steep drops in the new member states from Eastern and Central Europe. However, “Fertility as measured by the period total fertility rate (TFR) rose in the large majority of European countries between 1998 and 2008. This trend represents an unexpected reversal from the historically unprecedented low levels reached by most countries in the 1990s or early 2000s. Increases from these minimum levels have exceeded 0.2 births per woman in 19 European countries.” Bongaarts and Sobatka, 2012. Your handout shows this pattern of childbearing recuperation in country specific detail. Recuperation from the micro-level implies recovery from a delay and indeed to understand period changes in fertility across Europe we need to consider the shift towards later ages at childbearing which pushes births in to later years. How to explain fertility decline/low tfr’s demographically ? • Postponement: • Increasing length of the first birth interval. • Postponement opens the possibility that priorities will shift to non-familial aspirations and activities. • “Confronting demographic change: a new solidarity between generations” issued • in 2005 by the European Commission indeed recognises the role of the postponement of childbearing in shaping completed fertility, one of the basic trends that are targeted by European policy-makers: “The baby-boomer generation has had fewer children than previous generations, as a result of many factors: difficulties in finding a job, the lack and cost of housing, the older age of parents at the birth of their first child, different study, working life and family life • choices” (Commission of the European Communities 2005, p. 3). • Childlessness: delayed / foregone • One trend accompanying fertility decline is the increase in the proportion of women having no children. This may be an intentional outcome, an unintended one or somewhere in between but it has important implications for family structure. Handout: % of women ages 33-37 without children • The range of variation is impressive. 7.1% in Lithuania to 34.2% for Italy. • The correlation between the level of childlessness and the TFR is clear but not perfect. (e.g. Finland has a level of childlessness of 30.9 but a TFR of 1.8. Trends in nonmarital childbearing • More socially progressive countries, such as Sweden, have led the way in nontraditional forms of family formation. • But young parents in many other countries adopted similar lifestyles. In 2011, 40 percent of births in the European Union took place outside of traditional marriage. • There are eight EU member countries where half or more of births are nonmarital: Belgium, Bulgaria, Estonia, France, Iceland, Slovenia, Norway, and Sweden. Iceland has the world's highest proportion at 65 percent. • The import of nonmarital childbearing almost certainly varies according to the nature of cohabitation in the society. Living arrangements of children: Handout household type in which children live, 2007. • The % of children not living with at least one parent is rather small in all countries but still ranges from .03 in the Netherlands to 3.3 in Latvia (a factor of 10). • The % of children living in one parent families is highest in the UK and Ireland (more 20%) along with the Baltic countries. Living apart together: alternative family form? Grandparents and Grandchildren: a brief overview. • Leaving aside the question of co-resident extended families we can consider how frequent grandparents and grandchildren are potentially available in each others lives. • With prevailing standards of mortality in Europe most people will have the majority of their grandparents available during their childhood. But as they age the presence of grandparents will erode. Grandparents roles and agency. Not surprising grandparents provide a significant portion of childcare in some European countries. One element of this arrangement is the greater amount of trust that their offspring hold with them relative to the formal care institutions. Reciprocal influences are likely at work since contexts where these arrangements are most prevalent are ones with the weakest state support for formal care. According to a recent study by Jan Van Bavel and colleagues, grandparent may be seeking this role with implications that could reverberate back on the welfare state. Their study reports that persons with grandchildren are more likely to retire early than those without grandchildren controlling for other factors. Divorce: Cross-national differences A retreat from marriage accompanied by a rise in divorce. • Between 1980 and 2003 the crude marriage rate fell from 6.7 to 4.8. While the crude divorce rate increased from 1.5 to 2.0 per 1,000 in the population. Increases in divorce can have feedback effects on marriage and thus lead young persons to postpone or forego marriage. • Divorce rates tend to be lower in the Southern member states and higher in Central Europe, the north and Belgium. • The rise in divorce has generated increasing variation in families and households. • Increases in births outside of marriage, single parent households, step – families are all part of this mix. Family Policies in Europe • What are the range of family policies in Europe? • Do they matter for fertility, for education, for family as experienced? Family policy has a diversity of aims. • • • • • • Poverty reduction and income maintenance Direct compensation for economic costs of children. Fostering employment by reconciling work and family life. Improving gender equity Support for early child care development. Raising birth rates. : Source • Oliver Thevenon: “Family Policies in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis.” Framing the Importance of Family Policy: The low fertility issue. • “Europe is facing a demographic challenge based on the conjuncture of population ageing and shrinking labour force that in the long run jeopardizes economic growth and sustainable development. The current situation is the outcome of three trends: i) long-term below-replacement level period fertility (that is less than 2.05 children per woman on average), ii) increasing longevity and iii) growing proportion of people in ages of the late 50s and above in the labour force.” The question of demographic sustainability • The long-term risks are obvious both in terms of future labour supply, economic competitiveness (as young workers are more willing and able to adapt to new technology, labour market restructuring or other changes in economic production) and of the sustainability of welfare states that assume that the productive workforce will provide the resources to shoulder the costs of care for the aged and the disabled (McDonald and Kippen, 2001; Lutz and others, 2003; Bongaarts 2004). Driving forces of postponement and lower fertility and other family related change: • 1. Broader context of SDT: ideational change, value shifts etc. • “…Liefbroer (2005), who documents that the transition to parenthood is postponed among young adults who value individual autonomy and think that having a child will negatively influence their autonomy.” • “They show that men who are not holding traditional attitudes towards gender equality tend to postpone childbearing as compared to those who do hold traditional attitudes. No such effect is found for women.” • 2. Rise in Female Education – Probably both a cause and a consequence • • 3. Risk and Uncertainty – Rising likelihood of divorce and indeed the fragility of unions in general, deteriorating stability and earning power on the labor market especially for men. • 4. Geo-Political Structural Shifts – (Eastern/former Soviet Europe) associated policy shifts undercutting family support that once could be assumed albeit at a rather low level. • 5. Work-family imbalance: – A more proximate cause that has multi-faceted impacts on the family and not just a fertility effect. Structural factors that shape the tempo and quantity of fertility • “ Opportunity Costs of Childbearing” In the first instance considered in economic terms : How much potential income does a women forfeit if she drops out of the labor force to bear and raise a child? Immediate and long term consequences: Non-economic considerations as well. Social and avocational interests may have to be curbed “Work-Family Incompatibilities or Imbalances” This concept is related to the opportunity costs but tends to emphasize time as well as money. To what extent are the hours and costs of market work in conflict with aspirations for the quality and numbers of children that are desired. What are the institutional arrangements that shape the level of incompatability? Work-family balance, the lynchpin. • Why do we care about the connections between work and family? – Individuals face a challenge balancing two time-intensive activities of career (work) and parenthood (family) during a time of delayed childbearing and extended education. This challenge is faced by many individuals, and can have serious consequences on individuals’ decisions on family formation (childbearing), Their own wellbeing and the wellbeing of their children. From a demographic perspective, work-family conflict is believed to reduce aggregate fertility. • What is happening now? What are some recent trends? – With extended education, labor market transformation, globalization, declining real wages in some contexts and longer work hours, different individuals are making different decisions about work and family. Addressing work-family imbalance What causes family conflict? • Time pressures • Family burdens • Work demands • Multiplied by lack of financial resources or assistance in kind. How have states and social institutions responded? • 1. Parental leave schemes • 2. Publically subsidized and maintained day care facilities • 3. Flexible work schedules • Considerations: • • • Non-standard work hours may have there own negative consequences. (nights, weekends, shift work) As men become more involved with care-giving and domestic chores they may tend to experience more conflict. How have states and social institutions responded? • 1. Parental leave schemes • 2. Publically subsidized and maintained day care facilities • 3. Flexible work schedules • Considerations: • • Non-standard work hours may have there own negative consequences. (nights, weekends, shift work) As men become more involved with care-giving and domestic chores they may tend to experience more conflict. Two studies of family policy: • Stier, Haya, Noah Lewin-Epstein and Michael Bruan. “Work-family conflict in comparative perspective: The role of social policies.” Research in Stratification and Mobility 30: 265-279. • Presents multi-level models of work family imbalance with policy related measures. • Thevenon, Olivier. 2011. “Family Policy in OECD Countries: A comparative analysis.” Population and Development Review 37(1): 57-87. • Factor analysis categorizing family policies. Work-family balance across countries: Work family imbalance, OECD What factors predict work family imbalance? • Individual level factors • Women have a higher work-family conflict than men. • Older experience greater conflict than younger but the effect flattens at older ages. • Married less conflict than not married. • Presence of children more imbalanced. • Higher the number of working hours the more conflict. • Greater job authority more conflict. • Country level factors • Percentage of children in day care is negatively related to imbalance. • Also the gender gap in perceived conflict is lower in countries with greater job Gender specific analyses. Women • Policies have been more designed to reduce conflict for women. • Level of conflict is reduced in countries with more generous maternity/paternity leaves. • Presence of children is associated with at greater sense of conflict but this effect is smaller in countries with a greater provision of day care facilities. Thus policy does matter. • Also in countries scoring higher on the Flexibility Index the effect of children is even greater than in countries with lower scores. Thus suggesting the double-edged sword of nonstandard work schedules. Gender specific analyses. Men • Presence of children and high work demand increase perceived conflict. • Self-employment is associated with higher conflict for men, but perhaps lower conflict for women. • Country level child-care is related to imbalance in a similar way that it is for women. • But this effect is not different between men with and without children. Theveron: Input policies and investments: Cross national investment in early childhood Fertility recuperation in Europe Significant amount of recuperation in many countries in Europe in the last decade or so. Why? • 1. We just have to get developed enough. At high levels the Human Development Index becomes positively related to fertility. • 2. The low-fertility of some European societies was more a matter of the effect of postponement on the TFR than a real move to lower family sizes. (At least for some countries.) • Two answers not necessarily contradictory. SDT and Fertility Human Development Index and Fertility Formal child care, benefits for children • Formal child care has been one of the most crucial areas of family policy reform in the EU, particularly in the light of the objectives set by the Barcelona European Council 2002 to provide child care to at least 33 percent of children under three years of age and to at least 90 percent of children between three years old and the mandatory school age by 2010 (European Union, 2002). • Growing body of studies are reporting positive effects of high quality public day care on child development outcomes (behavior and achievement; cognitive and non-cognitive skills). These positive effects don’t necessarily apply to family day care. Benefits tend to be greater for children from less advantaged backgrounds. • Additional positive effects are reported in the case of long term outcomes. What does the Nordic model look like with respect to reducing workfamily incompatibility? The Case of Sweden. • “Swedish family policies are not directly aimed at encouraging childbirth. Their main goal has rather been to support women’s labourforce participation and to promote gender equality. The focus is to strengthen individuals so that they are able to pursue their family and occupational tracks without being too strongly dependent on other individuals.” • Policies are aimed at individuals and not families as such. • They are to help individuals, men and women, have the number of children that they want. But many say that they want more than two. The reconciliation of family and working life of women has been facilitated by: (i) individual taxation, which makes it less attractive for couples to pursue gendered segregation of work and care, (ii) an income-replacement based parental-leave system, which gives women incentives to establish themselves in the labour market before considering childbirth, and (iii) subsidized child-care, which allows women to return to work after parental leave. For a birth that occurred in 2005, parents get 80% of the salary for thirteen months. Sweden also has direct child allowances as do a number of other European countries. But, most social scientists believe that allowances are not sufficient to significantly impact the fertility rates of developed societies. Caregiving and depression: social policy success? Typologies of family systems in Europe? • In an analysis of Western European family structure, Berthoud and Iacovou (2004), proposed a spectrum ranging from Northern/Protestant to Southern/Catholic. • Scandinavian countries are characterised by small households (particularly single-adult and lone-parent households), early residential independence for young people and extended residential independence for elderly people; cohabitation as an alternative to marriage; and an almost complete absence of the extended family. • “Southern European countries are characterised by relatively low levels of non-marital cohabitation, by extended coresidence between parents and their adult children, and by elderly people with their adult offspring; this, together with a much lower incidence of lone-parent families, make for much larger household sizes.” • Reher (1998) outlines a typology based on geography and the familialistic legacy of the Catholic church. ‘Northern’ cluster (Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, the Low2 Countries and [much of] Germany and Austria), characterised by ‘weak’ family ties, early home-leaving, and a sense of social rather than familial solidarity with elderly or weak members of society; ‘Southern’ cluster (the Mediterranean countries, including Portugal) characterised by ‘strong’ family ties, later home-leaving, and a more family based sense of solidarity. He notes that Ireland is an indeterminate case, being geographically Northern, but having much more in common with the Mediterranean countries in terms of family structures. In fact to explain variation in the family arrangements across Europe, it is necessary to consider institutional (welfare state, economy) and normative factors and to consider the interplay between the two. • Backup slides:1 Measuring perceived work-family conflict. • How often has each of the following happened to you during the past three months? 1. I have come home from work too tired to do the chores which need to be done. • 2. It has been difficult for me to fulfill my family responsibilities because of the amount of time I spent on my job. • 3. I have arrived at work too tired to function well because of the household work I had done. • 4. I have found it difficult to concentrate at work because of my family responsibilities. • • The answers ranged from 1 = several times a week to 4 = never. Low fertility spiral/trap • Bongaarts says that to change behavior you must act on a bigger scale. Incentives must be much larger and that is expensive. McDonald has hypothesize a kind of threshold effect where once fertility goes below about 1.5, that the likelihood of recovery is rather low. Lutz is credited with calling it the low fertility trap. “...new social norms created by low fertility rates create a selfreinforcing negative feedback loop.” Ideal family sizes dropped to 1.7 in Germany and Austria 30% of young Germans report that they intend to have no children • But clearly not all countries have gotten stuck.