Chapter 3

advertisement

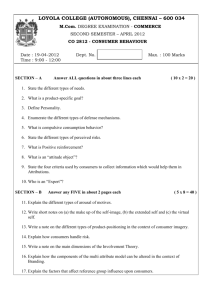

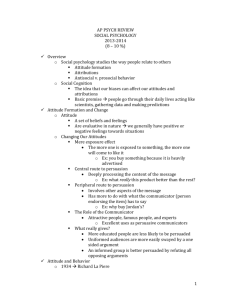

Chapter 3 Assessing Motivation to Read Introduction • The Relation Between Reading and Motivation • Motivation Leads to Engagement The Relation Between Reading and Motivation Reading Motivation and Engagement • In summary of research, Commission on Reading noted positive link between skilled reading and the reader’s interest in the content, as have other reading experts before them (e.g., Anderson, Hiebert, Scott, & Wilkerson, 1985). • Others make even stronger statements. Smith (1988) concluded that, “the emotional response to reading…is the primary reason most readers read, and probably the primary reason most nonreaders do not read” (p. 177). How Motivation Impacts Reading Development Motivation and Learning to Read • Guthrie and Humenick (2004) concluded that, “a motivated reader is not likely to automatically gain these complex cognitive competencies [reading skills] independently. The unmotivated reader, however, is quite unlikely to gain these reading competencies at all” (p. 351). Motivation and Learning to Read • Guthrie and Humenick (2004) studied the relation between motivation and acquisition of comprehension skills. • They identified 12 dimensions of motivation for reading. • They categorized the influence of these 12 dimensions within three more general types of motivation: • external (or extrinsic) motivation • internal (or intrinsic) motivation • self-efficacy Importance of Reading Self-Efficacy • Reading Self-Efficacy • Students’ beliefs in their capacity to read well, and their attitudes about anticipated success or failure • Confident students are more likely to engage in reading and to learn from text • According to the literature, self-efficacy appears to be the most important motivational influence (Berkeley, Mastropieri & Scruggs, 2011). Instructional Practices that Positively Influence Reading Motivation • Creating knowledge goals that emphasize learning content consistent with background knowledge, interests, and connections to larger goals. • Allowing student choices regarding reading content and reading time. • Assigning interesting texts based on students interests, use of illustrations, and consideration of relevance to background knowledge. • Allowing social collaboration based on joint assignments. (Guthrie and Humenick, 2004) How Reading Attitudes are Formed • From our interactions with reading content itself. • From interactions with models that may influence perceptions regarding the reading process, such as parents, peers, and teachers. • Influenced by instructional methods. • Influenced by gender (girls have more positive attitudes toward reading than boys), but not much by ethnicity. • Reading attitudes tend to worsen over time, particularly for poor readers. (McKenna and Stahl, 2009) Reading Attitudes • Number of reading interests decline with age. • Influence of gender increases with age, but girls are more likely to read “boy’s books” than are boys to read “girl’s books”. • Typical male interests include science, machines, sports, and action/adventure, while typical female interests include interpersonal relationships and romance, and both males and females seem interested in humor, animals, and the unusual. (McKenna & Stahl, 2009) Motivation Leads to Engagement: Reading Engagement • Engaged readers focus on reading to understand, to make meaning of text, to avoid distractions, and to exchange ideas and interpretations of text with peers. Their reading behaviors reflect devotion to reading across time and genre and result in important learning outcomes. • Disengaged readers are inactive, uninvolved, and tend to minimize effort during prescribed reading lessons and resist reading during free time. Engaged Readers Are Motivated • All experts converge on the notion that engaged readers are goal driven and strategic; they are motivated to obtain meaning from text, to read. • Importantly, engaged reading is strongly associated with reading achievement (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000). Engaged Readers Read More • As engaged readers seek reading opportunities, they build reading skills. • As they become better readers, they tend to read more. • This reciprocal relation has been referred to as the Matthew effect by Stanovich (1986), after the Biblical story revealing the tendency for the rich (using their resources) to get even richer. Goals and Grades for Reading • Share goals for reading with students. • Separate grades for effort from grades for achievement. (Caldwell, 2014) Students’ intrinsic motivation for learning (and reading specifically) tends to decrease across elementary school years and extrinsic motivation increases as they become more focused on grades and performance compared to peers, although this pattern does not characterize all students and has not been found in all studies. (Gottfried, 1990) Importance of Assessing Affective Aspects of Reading According to Afflerbach and Cho (2010), “Given the potential power of affect to influence reading development, assessment of affect should be a priority, yet it isn’t” (p. 498). Importance of Self-Efficacy • Positive academic self-efficacy is considered critical for developing academic skills because of its motivational influence. • First described by Bandura (1977; 1978; 1986), it refers to an individual’s beliefs about his/her ability to perform an academic task successfully. • Those beliefs are in turn influenced by students’ causal attributions, i.e., the extent to which they believe success or failure results from ability, effort, task difficulty, or luck. Appendix B How Reading Motivation Is Assessed Assessing Motivation • • • • • • • • • Self-reports Anecdotal notes Classroom observations Reading journals Interviews and surveys Sentence completion Interest inventories Thought bubble Attitude inventories: ERAS, RSPS Classroom Observations: Figure 3.1 • Anecdotal Observations • Nonjudgmental language • Systematic Observation • Frequency Count • Record number of times a particular behavior occurs within a given time period Reading Journals • Variety of purposes • • • • Assess reading self-efficacy Keep record of what student has read Build writing skills Gain insight into student’s choices and interests • Should not be treated like book reports Sentence Completion • • • • • • • • • “The best thing about school is_____.” “My teacher helps me ____.” “The thing I hate most about school is ___.” “I like to read about____.” “When I am older I want to read about ____.” “My friends think reading is ____.” “My favorite book is ___.” “The thing I hate most about reading is ____.” “My favorite time to read is _____.” The Affective Elements of Reading Motivation (e.g., Attributions, Beliefs, Interests, Self-Efficacy) How Related Affective Elements Are Assessed Interest Inventories • Figure 3.4 • The Reading and Activity Interest Inventory (RAII) Attitude Surveys • Elementary Reading Attitude Survey (ERAS), developed by McKenna and Kear (1990) to determine student attitudes toward recreational and academic reading activities • Only 20 items • Assesses academic and recreational reading attitudes • Normed on national database Attitude Surveys • Reader Self-Perception Scale (RSPS), developed by Henk and Melnick (1995) to assess how students feel about themselves as readers, consists of 33 items along four dimensions of selfefficacy • • • • Progress Observational Comparison Social Feedback Physiological States • RSPS2 is similar to SPS but is appropriate for older students (i.e., adolescents) Attitude Surveys • Motivation for Reading Questionnaire (MRQ) scale, developed by McKenna and Stahl (2009) to assess various dimensions of elementary-age students reading motivations • 54-item questionnaire • Takes about 20–25 minutes to administer Attitude Surveys • Reading Motivation Scale (Bell & McCallum, 2015) • Table 3.1 • Determines a student’s level of reading enjoyment and motivation • 20-item self-report scale can be administered to students who are capable of reading the items in group form • Can be read to younger or less capable students • Readability of directions is 5.3 grade level based on Flesch-Kincaid in Microsoft Word; the actual items are at a much lower readability level Attitude Surveys • Adolescent Reading Attitudes Survey (ARAS), developed by McKenna, Simkin, Conradi, and Lawrence (2008) • Determines reading attitudes of adolescents regarding recreational and academic content in either print or digital format • Can be scored to reveal positive, somewhat positive, neutral/indifferent, somewhat negative or negative attitude about recreational reading in print settings, recreational reading in digital settings, academic reading in print settings, and academic reading in digital settings Interviews • Can help determine student reading-related interests and motivation • Interview is driven by kind of information sought • Initially ask general, open-ended questions, followed by increasingly specific questions • Interviews may be helpful in obtaining information about a student’s goals for reading, interests, hobbies, and beliefs about reading success and failure (e.g., attributions) Assessing Attributions • Attributions are studied because of their power to influence academic and social skills success (Bell & McCallum, 1995) • Ability • Effort • Luck (or Chance) • Task Difficulty (or Context) Incremental View of Ability • Effortful students are more likely to hold an incremental view of intelligence and related abilities, including reading, rather than an entity or innate view. They are more likely to assume that their ability is malleable, fluid, and changeable, and so is reading success. • Students who believe that reading ability is innate, fixed and stable, i.e., out of their control, have an entity view and are more susceptible to the effects of learned helplessness and are more likely to give up if they perceive reading as difficult. Student Reading Attribution Scale (SRAS) Table 3.2 • SRAS informally assesses the reading attributions most related to reading success and failure. • 20 hypothetical reading success or failure scenarios (items) • Can be administered in group form or individually • Students rate their level of agreement for two attributions that might account for outcomes described • Score indicates the extent to which students express incremental versus entity or innate view of reading success and failure (Bell & McCallum, 2015) Teacher Self-Assessment • • • • • • • “My classroom décor promotes interest in reading because ___.” “I encourage students to read by___.” “Good things happen in my class when___.” “I hold students accountable (nonpunitively) for reading by___.” “When I model reading behavior, students ___.” “When I encourage weak readers to read more, they ___.” “When I encourage good readers to try new genres, they ___.” Summary • The Relation Between Reading and Motivation • Motivation Leads to Engagement