We can set standards and goals for ourselves that are

advertisement

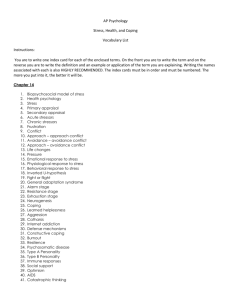

Stress management Introduction Stress is a routine part of our lives. It is a natural and unavoidable part of all our lives. Certain amounts of stress are beneficial; however, sometimes the level of stress can become burdensome. Being able to manage and control stress is a useful skill, for life as an individual. As put simply, “One of the difficulties about stress is that it can work for you or against you, just like a car tire. When the pressure in the tire is right, you can drive smoothly along the road: if it is too low, you feel all the bumps and the controls feel sluggish. If it is too high, you bounce over the potholes, and easily swing out of control” (Butler & Hope, 1995, p. 207). People have always reacted and responded to stress and the paradox is that, many people think they understand stress. In reality, however, stress is complex and often understood sparingly. About 70 years ago, Walter Canon, a physiologist, studied the way a person physically responds to stress and thus, the study of how the human body responds to stress continues today. One thing we need to know however is that our "threats" or stressors are more psychological-than physical. It is important to note that not all stress is bad; stress can result in a competitive edge and force, positive changes. It involves multiple, complex physiological changes in response to perceived demands and/or threats. In many ways, stress can be beneficial in that it pushes us to peak performance. It keeps us alert and focused, motivates us to face challenges, and drives us to solve problems. When most of us speak of stress, however, we refer to feelings of having too much pressure. "Negative stress" occurs when we feel overwhelmed by emergencies and/or lack the skills to cope effectively with difficult experiences. But stress is not an external event or situation. The experience of stress has to do with our physical, emotional and psychological capacity to respond to that stress. A 1994 national Gallop Poll found adults rated their job as the causing the most stress (71%), followed by money problems (63%), and family (44%). More importantly, stress is directly associated with quality of life. Therefore, everyone should learn to recognize the stressors in their life and practice stress management techniques. A little stress is good, but too much can make us difficult to be around, less effective managers, and can even make us physically sick Aim This module is designed for use by participants who want to help develop their ability to cope with stress and provides information and strategies for use. The goal of this module is to help give participants a better awareness and understanding of stress; provide coping strategies for avoiding distress and to promote better adjustment techniques. It further helps participants to establish an optimal level, not too high and not too low - to learn how to thrive as well as survive. Specific objectives To help participants learn more about the causes and implications of stress. To help participants become aware of the signs and symptoms of stress early, to prevent chronic stress. To help participants identify potential sources of stress and to develop an awareness that they can cope with the stress in their lives. To help participants identify their own optimal level of stress. Stress Defined Hans Selye, a pioneer in stress research, has defined, as "stress is the nonspecific response of the body to any demands made upon it". According to Oxford Dictionary “Stress is a state of affair involving demand on physical or mental energy". It is an internal state or reaction to which we consciously or unconsciously perceive as a threat, either real or imagined. Stress has been further defined as the arousal of the mind and body in response to demands made on them. Simply put, stress is a normal, universal human experience. There are many different definitions and theories of stress. However, a commonly recognized one is the interactionist model of stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). It suggests there are three key components involved: - The situation and demands - Our subjective appraisal of the situation - Our perceived resources for meeting the demands These demands or situations could include financial problems, arguments, changes in work circumstances, etc. These are events, hassles or changes that occur in our external environment that may be physical or psychological. They are sometimes referred to as stressors. Appraisal of the situation refers to how we interpret the situation or demand. For example, an event occurs. Person A may see it as stressful while Person B does not. Thus Person A will probably have a reaction to the stressful situation, either physiological or emotional. Resources refer to our ability to cope with the demand or stressor, for dealing with possible or real problems. Again, an event occurs, Person A and Person B both perceive it as stressful, but Person A believes she has the resources to cope but Person B believes she doesn’t, and they will respond accordingly. Types of stress There are basically two types: Eustress and Distress. Eustress, or good stress, is stress that benefits our health, like physical exercise or getting a promotion. Distress on the other hand, is stress that harms our health and often results from imbalances between demands made upon us and our resources for dealing with these demands. The latter is what most people think about when they talk about stress. However, if handled well stress can increase motivation and stimulate us. Optimal Level of Stress Everyone has an ideal level of stress, but it differs from person to person. Basically, if there’s not enough stress then performance may suffer, due to lack of motivation or boredom (See Figure 1). However, too much stress results in a drop in performance as a result of stress related problems like inability to concentrate or illness. We must learn to monitor our stress levels, firstly to identify our own optimum level of stress and secondly to learn when we must intervene to increase or decrease our level of stress. This way stress works for us. By managing stress we can improve our quality of life and do a better job, either in academic life or professional life. If stress is not handled properly it can increase the negative consequences for an individual. Optimum Stress Area of Optimum Performance Low Stress Boredom Figure 1.: The relationship between stress and performance High Stress Anxiousness Unhappiness Signs and Symptoms of stress People will have their own personal signs or reactions to stress, which they should learn to identify. They generally fall into three categories: physical, cognitive and emotional. Many of these symptoms come and go as a result of short-term stress. However, symptoms that are associated with more longterm, sustained stress can be harmful. Consequences can include fatigue, poor morale and ill health. High levels of stress without intervention or management can contribute to mental health problems (e.g. depression, anxiety, interpersonal difficulties), behavioural changes (e.g. increased alcohol intake, drug abuse, appetite disorders) and sometimes involve medical consequences (e.g. headaches, bowel problems, heart disease, etc.). Some of these signs are listed below. Physical (physiological and behavioural) -Racing heart/thoughts/heart disease -Rushing around -Cold, sweaty hands -Working longer hours -Headaches/lack of appetite/over eating -Losing touch with friends -Shallow or erratic breathing -Fatigue/High Blood Pressure -Nausea or upset tummy or Constipation -Sleep disturbances - Insomnia/diarrhea/indigestion -Weight changes -Shoulder or back pains -Family conflicts -Extreme anger and frustration -Depression/absenteeism There are well established links between stress and many types of illness. However, these physical symptoms could result from medical or physiological problems rather than be completely stress related. Medical advice should be sought whenever someone believes he or she may have an illness, e.g. chest pain or weight changes. Cognitive (or Thoughts) Emotional (or Feelings) -Forgetting things -Increased irritability or anger -Finding it hard to concentrate -Anxiety or feelings of panic -Worrying about things -Fear/self-rejecting thoughts -Difficulty processing information -Loneliness -Negative self-statements -Increased interpersonal conflicts Everyone has developed his or her own response to stress. The key is to learn to monitor your own signs and become aware of when they are indicating the stress level is unmanageable. Demands and Resources Demands The demands or stressors we experience can come from internal or external sources. External sources of stress are the demands or pressures from job, demands of family or friends, physical or environmental factors (noise, caffeine). Recent changes can also be stressful events. For example, looking for a job, moving, trying to find accommodation, holidays, and so forth. Some common stressors include the transition to college, academic concerns (difficulty with material, lack of motivation), time pressures, financial concerns, family (conflict with parents); social (loneliness), or developmental tasks of late adolescent/early adulthood (moving from dependence to autonomy, establishing identity). Internal sources of stress result from our reactions to these demands and the demands we put on ourselves. For example, if you feel there are many demands, and not enough resources to cope then you may feel stressed. You may tell yourself “There’s just too much to do.” Our own wants, feelings and attitudes can also create stress. For example, when we want to do a perfect job, or expecting others to be as motivated as ourselves. A student’s sense of adequacy or confidence may also influence how they experience stress (Aherne, 2001). Resources These refer to our ability to cope with the stressors, either by our appraisal or by our strategies for dealing with them. With coping resources, we can reduce the external demands. For example if the demand causing stress is financial concerns, then finding sources of funds or making a budget would be a resource for coping. Alternatively, we can reduce the internal stressors, for example changing our attitude or perception. Or we can do both. In addition to coping resources, there are some indications that personality characteristics interact with stressors and coping resources. For example, “attachment style” may influence how comfortable people are in seeking support. People who feel comfortable seeking the support of friends are often better able to cope; people who don’t seek support are more likely to cope with stress by avoiding demands, which can cause trouble later on. Thus how secure one is about relationships may indicate which coping resources will be most useful (Lopez & Brennan, 2000). Social support is also a significant factor in enabling people to effectively manage their stress. It refers to our sense of belonging, being loved and accepted. Social support interacts with stress to offer people a buffer from the negative effects of stress (Brotheridge, 2001). Social support may elicit an appraisal of events as less stressful, may inhibit dysfunctional coping behaviors, or may facilitate more adaptive coping behaviours (Cohen & Wills, 1985). This is one reason why it is important for students to integrate into the academic community and establish relationships with other students, academic and support staff. Causes of stress Job Insecurity Organized workplaces are going through various changes and consequent pressures. Reorganizations, takeovers, mergers, downsizing and other changes have become major stressors for employees, as companies try to live up to the competition to survive. These reformations have put demand on everyone, from a CEO to a mere executive. High Demand for Performance Unrealistic expectations, especially in the time of corporate reorganizations, which, sometimes, puts unhealthy and unreasonable pressures on the employee, can be a tremendous source of stress and suffering. Increased workload, extremely long work hours and intense pressure to perform at peak levels all the time for the same pay, can actually leave employees physically and emotionally drained. Excessive travel and too much time away from family also contribute to an employee's stressors. Technology The expansion of technology has resulted high expectations for productivity, speed and efficiency, increasing pressure on the individual worker to constantly operate at peak performance levels. Workers working with heavy machinery are under constant stress to remain alert. Both the worker and their family members live under constant pressure and mental stress. There is also certain factors which are forcing employees to learn new software all the times. Workplace Culture Adjusting to the workplace culture, whether in a new company or not, can be intensely stressful. Making one adapt to the new situation and other aspects of workplace culture such as communication patterns, hierarchy, dress code if any, workspace and most importantly working and behavioral patterns of the boss as well as the co-workers, can be a lesson of life. Maladjustment to workplace cultures may lead to subtle conflicts with colleagues or even with superiors. In many cases, office politics or gossips can be major stress inducers. Lack of motivation also affects his ability to carry out job responsibilities. Personal or Family Problems Employees going through personal or family problems which lead to tensions and anxieties in the workplace. Job Stress and Women Apart from the common job stress, women may suffer from mental and physical harassment at workplaces; Sexual harassment in workplace has been a major source of worry for women. A constant source of tension for women in job sectors like subtle discriminations at workplaces, family pressure and societal demands add to these stress factors. Understanding stressors in context Everybody suffers from stress. Relationship demands, physical as well as mental health problems, pressure at workplaces, traffic snarls, meeting deadlines, growing-up tensions—which leads stress. Let’s examine stressors in the light of: Work: In what way is stress related to your work? What effects do deadlines have on you, what is the nature of the working conditions, and what effect does lack of promotional opportunity or an insecure job future have on you? Can you change the situation? Can you take training courses to enhance your promotional opportunities? Are deadlines just part of your job and do you need to learn to endure and better cope with them? Meditation or relaxation techniques may help you get through the day and an exercise program help you leave the worries at the office. Relationships: To what extent is your stress caused by your personal relationships? Can you obtain family counseling to improve the communication with your adolescent daughter? Is the stress the result of the lack of an intimate relationship? Do you want a relationship but thus fear keep you from taking steps to find one? Are you in a marriage that has lost its meaning? Do you see a pattern in your relationships, either in the type of person chosen or the end result? Can you go to counseling or contact your workplace employee assistance program (EAP) to get help in finding answers to these questions? Psychological: To what extent does the stress originate from within you? Do you feel inadequate no matter what you accomplish? Do you feel unattractive and undesirable even though others do not share this impression? Are you afraid to take actions to realize your potential? We reach adulthood with a host of past experiences, some we remember and some we do not. Even experiences we do not remember can affect the way we feel about ourselves. If a child was treated as inferior to his intellectually gifted older brother, this can continue to affect him in adulthood. This individual might be confused about why he never feels smart enough and/or why he obsessively must compete for first place with all males. To deal with stress that is the result of one’s thoughts, counseling can help you connect them to the original cause, and over time, disengage from that way of thinking. Environmental: Now moving back to the external, what effect does your environment have on your stress level? What role does your daily commute play in your stress, what about the noise level, the climate, and crime? Again, can you change it (save money and move to a better neighborhood), should you leave it, or must you find a way to endure it? Reactions to Stress Mainly there are two kinds of reactions to stress. Physical Reaction and Psychological Reactions Physiological Stress reactions The general adaptation syndromes consist of three progressive stages such as alarm reactions, the stage of resistance and the stage of exhaustion. The alarm reactions consists of complicated body and biochemical changes that produce similar symptoms regardless the type of stressor. The common symptoms are fever, head ache, loss of appetite and generally tired feeling. In stage of resistance, human organism develops an increased resistance to stressor. The alarm stage disappears and the body resistance rises above its normal level to cope up the continued stress. But this resistance includes increased secretions from various glands, lowered resistance to infections and disease to adaptation. Stress induced peptic ulcers and high blood pressures are the common disorders induced by stress. Chronic stress leads to the stage of exhaustion. Body defenses break down, adaptation energy runs out and the physical symptoms of the alarm reaction reappear. Psychological Reactions. It consists of wide variety of cognitive, emotional, and behavioural response to stress. Most stress evoke anxiety-the vague, unpleasant feelings that something bad is about to happen. The most familiar psychological reactions to stress are defense mechanisms which protects oneself from perceived threat. Once a stressor has been interpreted as threatening, a variety of cognitive functions may be adversely affected. Stress also interferes with our judgment, problem solving and decision making. Stress also evokes a wide range of emotions, ranging from a sense of exhilaration, in the face of minor, challenging stressors to more familiar negative emotions of anger, fear, jealousy and discouragement. People behave under stress depends partially on the level of stress experienced. Mild stress energizes us to become more alert, active and resourceful. Moderate stress tends to have disruptive effect on our lives especially on complex behaviour. Under moderate stress people become less sensitive to their surroundings, easily irritated and more apt to relay on certain coping devices. Effects of stress Stress can produce feelings of frustration, fear, conflict, pressure, anger, sadness, inadequacy, guilt, loneliness, or confusion. Individuals feel stressed when they are fired or lose a loved one (negative stress) as well as when they are promoted or go on a vacation (positive stress). Individuals believe they must avoid stress to live longer. In the workplace, stress can affect performance. Individuals under too little stress may not make enough effort to perform at their best levels, while those under too much stress often are unable to concentrate or perform effectively and efficiently. Statistics show that heart disease (35%) is the leading cause of death in the United States, followed by cancer (24%), stroke (7%), pulmonary diseases (4%), and accidents (4%). These are all related to stress in one way or the other. Stress plays a role in arthritis, the most common chronic health problem in the country. Pneumonia and influenza, the killers at the beginning of the century, garnered only 3% of the deaths in 1992. Medical science has had less success the on the life style-related disease of today. Stress is thought to affect our health as follows: By imposing long-term wear and tear on the body and mind, thereby reducing resistance to disease such as with colitis, cancer, migraines, or high blood pressure. By directly precipitating an illness such as a heart attack, tension headache, or depression By aggravating an existing illness such as arthritis, psoriasis, angina, diabetes, or hypertension. By precipitating unhealthy or even illness-generating coping habits such as smoking, alcohol abuse, overeating, or sleep deprivation. Managing Stress (Coping with stress) “The breadth of coping resources individuals have at their disposal can be a determinant of the degree of success and satisfaction they experience” (Baird, 2001, p.3). this part is aimed at: Providing participants with a range of coping strategies Allowing them the opportunity to practice coping strategies and Encouraging participants to lay the foundations for a healthy life style that reduces stress. The three components of stress are the: Situation and its demands, Subjective appraisal of the situation and Perceived resources for coping with the demands. Management of stress can be aimed at any or all of these components. In other words, we can decrease the external demands or stressors; we can change or appraisals or we can increase our coping resources. Types of Coping Coping refers to the use of strategies to deal with problems, real or anticipated, and any possible negative emotions that may arise. This approach helps us to control our reactions to the demands placed upon us. We use actions, thoughts and feelings to cope. Different situations or stressors call for different kinds of coping. Problem-Focused Coping is aimed at changing a situation or its accompanying demands. It is most appropriate when you have some control over a situation or when you can manage the problem in the environment. It uses specific activities to accomplish a task. For example, maybe a student is having difficulties with a roommate who creates a lot of distractions thus preventing the student from studying. Problem-focused coping would involve the student negotiating a contract or using other problem-solving strategies to overcome the stressful situation. Using time management or seeking advice are other examples of this type of coping. Emotion-Focused Coping is aimed at dealing with the emotions caused by a situation and its demands. It is more appropriate when you have little or no control over a situation. This type of coping involves reducing anxiety associated with the stressful situation without addressing the problem. For example, in parental separation a student has no control over it but he/she could cope with any anxiety the event may cause. Sometimes people employ strategies to relieve stress that are short-term, and may actually contribute to stress – such as drinking or taking drugs, blaming others, avoidance or overeating. Many of the situations people face are best coped with by a combination of problem- and emotion-focused coping. In general flexibility, adaptation and persistence are crucial to success. Research has found an inverse relationship between believing one has adequate coping resources and the degree of depression and adjustment (Baird, 2001). Therefore we need to constantly seek to increase the coping resources. Coping Resources These resources can broadly be divided into: Cognitive coping strategies and Physical / behavioural coping strategies. Some of these coping strategies will suit some people, others will not. The key is to have a range of resources that can be applied, depending upon the situation and the individual. It is important to have strategies one is comfortable using. Cognitive coping strategies These refer to ways of dealing with stress using our minds. Cognitive coping strategies are a good way to combat stress-producing thoughts. As Shakespeare’s Hamlet said, “. . . for there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so. . .” Often people already use these cognitive ways of coping, but making them more conscious will increase their efficiency and effectiveness. Examples of these strategies are: Reframing: focus on the good not the bad; think in terms of wants instead of shoulds. It’s best if our thinking is related to our goals. For example, “I want to read and understand this chapter in Chemistry so I do well in my lab practical” instead of “I have to read this difficult chapter in Chemistry”. Challenging negative thinking: stopping the negative thoughts we may have about a situation or ourselves. Examples of negative thoughts include expecting failure, putting yourself down, feelings of inadequacy - a thought such as “Everyone else seems to understand this except me.” In order to gain control of negative thoughts or worries, you must first become aware of them. Next, yell “Stop!” to yourself when they occur. Try replacing with positive affirmations or at least challenge or question any irrationality of the thoughts. Positive self-talk: using positive language and statements to ourselves. These are sometimes referred to as positive affirmations; they are useful for building confidence and challenging negative thoughts. For example, “I can do this or understand this” or “I’ll try my best”. These work best when they are realistic and tailored to your needs and goals. Count to ten: this allows you time to gain control and perhaps rethink the situation or come up with a better coping strategy. Cost-benefit analysis: asking yourself questions about the worth of thinking, feeling or acting a particular way. “Is it helping me to get things done when I think this way?” “Is it worth getting upset over?” “Am I making the best use of my time?” Smell the roses: “Experiencing life as fully as possible requires conscious effort, since we become habituated to things which are repeated. Varying our experiences (such as taking different routes to school or work) can help in this process” (Greenberg, 1987, p. 129). Keeping perspective: when under stress it is easy to lose perspective; things can seem insurmountable. Some questions to ask yourself: Is this really a problem? Is this a problem anyone else has had? Can I prioritize the problems? Does it really matter? “Look on the bright side of life!” Cultivate optimism. Reducing uncertainty: seek any information or clarification you may require to reduce the uncertainty. It helps to ask in a positive way. Situations that are difficult to classify, are obscure or have multiple meanings can create stress. Using imagery/visualization: imagining yourself in a pleasant or a successful situation to help reduce stress. One way to use imagery is as a relaxation tool; try to remember the pleasure of an experience you’ve had or a place you’ve been. The more senses you involve in the image the more realistic, therefore the more powerful. This strategy is often combined with deep breathing or relaxation exercises. Visualization can also be used as a rehearsal strategy for an anticipated stressful event. For example, if you have a presentation to give, practice it in the mind a few times, picturing the audience’s reaction and even visualizing yourself overcoming any potential pitfalls. Behavioural coping strategies These refer to ways of dealing with stress by doing something or taking action to reduce the stress experienced. Examples of these strategies are: Physical exercise: aerobic exercise is the most beneficial strategy for reducing stress. It releases neurochemicals in the brain that aid concentration. For some people, even a short walk is sufficient to relieve stress. Relaxation from simple relaxation such as dropping the head forward and rolling it gently from side to side or simply stretching, to more complex progressive relaxation exercises. Progressive relaxation involves tensing and releasing isolated muscle groups until muscles are relaxed. Please refer to Handout – Five Minute Relaxation. There are also tapes and books available on this topic (available from the Student Counselling Service or the library). Breathing from simple deep breaths to more complex breathing exercises related to relaxation and meditation. Please refer to Handout – Deep Breaths. Smile and Laugh: gives us energy and helps to lighten the load; relaxes muscles in the face. Time management: specific strategies such as clarifying priorities, setting goals, evaluating how time is spent, developing an action plan, overcoming procrastination and organising time. These help us to cope with the numerous demands placed upon us, often a source of stress. Social Support/Friends: encourage the development and nurturing of relationships. There is an association between good social support and a reduced risk of drop out (Tinto, 1998). Seek Help: to help us cope with unmanageable stress. This is a sign of taking control, not of weakness. Performance and stress Most people find performance stressful, whether examination, interview, public speaking, practicals, etc. However, they need not cause distress. The following tips for managing the stress experienced as a result of performance situations can help students achieve their goals. Focusing on the process not the outcome. Being aware of the stress/performance curve and their own optimal level of stress. Learning and practicing coping skills – practice is important. Reframing evaluative situations – a learning experience. Keeping and using a sense of humour Maintaining one’s perspective Remembering that mistakes are part of learning Separating self-worth from performance Stress management toolbox Maintain Good Health Change Personal Habits Laugh Be Kind To Yourself Listen to Relaxing Music Exercise Regularly Talk Out Problems Laugh some more Eat Right Do Things You Enjoy Set Limits Get Enough Sleep Remember Habits Don't Abuse Alcohol/Drugs Limit Caffeine and Sugar Important Learn What Is Play Think Constructively Relaxation Be Realistic Make A List Take A Break Pace Yourself Manage Your Time Slow Down Techniques Practice Breathing Plan Alternatives Exercises Delegate Tasks Review Your Priorities Breathe Some More… Foundations for Lifelong Health – Reducing Long Term Stress For long-term management of stress, it is important to lay good foundations. Often when we are under stress, we ignore our health and relationships, yet when these are poor it can add to our stress. Avoid this cycle! Health, Nutrition and Exercise There is good evidence to support the idea that proper diet and exercise is the most effective way to protect us from the long-term effects of stress. Regular exercise, even of short duration, improves the functioning of the body (muscles, lungs, etc.) as well as psychological functioning (better concentration, feeling good about self, etc.). Even 30 minutes cumulative daily moderate exercise improves health. An excess intake of certain foods can encourage stress symptoms. Items that contain stimulants such as nicotine or caffeine affect the sympathetic nervous system which can bring on stress responses such as irritability or jitteriness. To help manage stress it is important to limit our intake of caffeine (coke, coffee, and tea, chocolate) and large amounts of sugar in a short time span. Like exercise, regular meals are the key; skipping meals is not a healthy option. Sometimes people try to cope with the symptoms of stress rather than dealing with the stress itself. For example, using alcohol to relax or taking sleeping tablets to help with sleeplessness. Lifestyle We make choices every day that affect our health. How we get to college or work, what we eat, what we do with our free time - all of these choices will have an impact. We probably all know someone who we think of as being “stressed out” – we may even avoid being around these people because they make us uncomfortable. In contrast, we also probably know someone who seems more able to just “go with the flow” and minimise the amount of stress in people’s lives. Think about the differences in people you know – what seems to be a healthy, balanced approach to life? “To prevent being caught up in the vicious cycle of stress, which leads to even higher levels of stress, you need: rest, to renew your energy; recreation, to provide you with pleasure and fulfillment; and relationships, as a source of support and perspective” (Butler & Hope, 1995, p. 217). In general, aim to make lifestyle decisions that attempt to eliminate distresses, modify stressful behaviours and increase healthy behaviours. Attitude We have control over our attitudes, unlike some other aspects of our life. We create, to a large extent, our reality through our expectations (self-fulfilling prophecy) and we can also change our physiology with our thinking. New research (Lyubomirsky, 2001) shows that motivation and evaluation of life circumstances can be modified with resulting improvement in positive affect and performance. This suggests that learning what motivates us then using it to improve our attitude will result in better life situations. In other words, unhelpful attitudes can increase the burdens and pressures we experience – thinking things like: “I have to get this done” or “I shouldn’t ask for help”. Healthier alternatives would be “I will do as much as I can in the allowed time” or “Everyone asks for help sometimes” (Butler & Hope, 1995, p. 216). We spend a lot of time relating to other people which can at times be satisfying or stressful. However, relationships can provide great support to help us deal with the stress in our lives. There are several factors to “forming harmonious relationships with other people - take a positive approach, project a positive image, be assertive, pay compliments where they are due (but be sincere), try to leave people pleased to have spoken to you” (Mind Tools, 1995). Alternative measures We can reduce stress by identifying what we do and do not have control over. We can identify problems and look for ways to solve them. We can utilize our capacity to think and reason and go through the following problem solving steps. This is like the Scientific Method: Define and state the problem. What do I feel? Why? Who? Where? When? What do I want? (Remember this from Assertiveness Training?) Search out known solutions to the problem or get advice from experts, trusted friends, or acquaintances, etc. We're human and usually have the same problems as everyone else. Identify several ways to solve the problem. We are allowed to use our brains. What are the possible outcomes? Try the way most likely to solve the problem and evaluate it. If it doesn't work, try something else - - not more of the same thing. If none of the solutions work, we have to be prepared to just let the problem go and get on with our lives. We don't have to like it, but, if we can't change it, we have to accept it. It makes no sense to ruin our serenity over things we have no control over. Medical science has found correlations between spirituality, religion, and health. We can also practice finding humor in things that happen around us. Laughing deactivates the stress response and seems to help us heal and stay healthier. Some of us have disabilities or physical or emotional problems that we must recognize and work around. They add to the difficulty of life. Some of these may actually be aggravated or caused by stress and may be alleviated when stress levels are reduced. As we grow older we find our energy levels, strength levels, hearing and vision acuity, and/or stamina levels may lesson which we will also have to work around. Healthy diet and exercise can help to stave off some of the deterioration. Just as we can choose to cut down on alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, and so forth, we can choose to eat healthy moderate meals, exercise, and get adequate rest. All of which can help to keep us balanced and in better health, more able to deal with life's little surprises. It is useful to recognize whether we are extroverts or introverts. Introverts like quiet times and a few close friends. Extroverts, on the other hand, like lots of activity and friends. One isn't better than the other. It's just that introverts may be better suited to certain occupations and extroverts to others. If we mistakenly assume we're extroverts, we may put ourselves in uncomfortable situations where it will be difficult to be successful. We need to identify what we really like and what situations make us feel good and comfortable. It is less stressful to find ourselves in uncomfortable situations if we at least understand why we feel the way we do. We are better able then, to either get out of the situation or accept it graciously until we can. We can set standards and goals for ourselves that are feasible, that is, we have the capabilities, the time, and there are opportunities for what we want to do. We must not set ourselves up for failure by expecting the impossible. Regardless of one’s personal history or strengths, we all have three choices in dealing with stress. We can change, leave, or endure the stressful situation. Change: Can you change the situation that is causing stress? If marital problems are causing you stress, can you and your spouse go to counseling to resolve the problems and eliminate the stress? Can you improve your health through adoption of an exercise program and healthier eating habits? Leave: If you cannot change the stressful situation, should you leave it? It is important to thoroughly explore the consequences of this action to assure you do not end up with more stress than which you started. Should you leave a bad marriage that shows no indication of improving, should you leave a job that you dislike, or should you move to the country to get away from urban crime? Endure: There may be stressful situations that you can neither change nor leave. Dealing with a family member’s terminal illness, staying in a job with high tension deadlines or dealing with financial problems are examples of situations that may have to be endured. Adopting a healthy life style of exercise, good nutritional and sleep habits, and relaxation techniques can condition one’s body and mind to constructively deal with these stressors. Different situations call for different responses as the above examples indicate, but developing, or revising a stress management plan, should always start with a thorough assessment. Identifying the source of your stress will help determine what actions to take. As there is always going to be stress that simply must be “endured,” techniques of doing this need to be part of everyone’s stress management plan. It is a way of conditioning the body and mind for the trip of life. Choose activities from each of the following categories: Relaxation Techniques: Practice meditation or a visualization exercise for at least 20 minutes a day. Progressive muscle relaxation techniques, yoga, stretching, and deep breathing exercises can also be utilized. Most bookstores have a section on personal health which includes stress management books and relaxation tapes. Exercise: Physical exercise needs to be part of everyone’s stress management plan. Exercise not only takes your mind away from your worries but can cause the release of hormones (endorphins) in the brain that promotes relaxation. Ongoing rhythmic exercises such as walking, jogging, biking, rowing, aerobic dancing, and swimming are particularly helpful as they exercise the heart and lungs as well as the psyche. Most important in a choice of exercise is to do something you most enjoy. It is crucial to structure exercise into your week just as you do work. Waiting until you feel like exercising is likely to result in a sparse exercise program. Exercise three to five times a week. You may want to find an exercise partner so you can socialize while you exercise. Nutrition: Most of us know what is healthy and what in not. Changing one’s eating habits is another story. We often hold on to our childhood foods as “comforts” from earlier days. Potato chips, hamburgers, and banana cream pie may remind us of carefree summer days but provides little benefit for our cholesterol level. Eating healthy does not mean depriving oneself of all one’s favorite foods, just limit them and see if you can find healthier “favorite” foods. Decrease fried and high fat content foods, limit sweets, and add fruits and vegetables. Foods high in vitamin B such as leafy green vegetables are particularly good for stress. Remember to watch you intake of caffeine, tobacco, and alcohol. Sleep: A large number of Americans function in a sleep-deprived state. Although there are individual differences, most adults function better on eight hours of sleep. Albert Einstein reportedly needed 11 hours (Schafer). Time Management/Prioritize: You cannot do everything at once, and depending on your lifestyle, may never be able to do all you would like to do (or feel you must do). Firstly, sit down and evaluate your life. Are you really spending it on the important things or are they getting lost in life’s race? Are you feeling stressed because you never seem to have time and energy to spend with those you love or your favorite activity? Divide your life into long and short term goals. What steps need to be taken to meet the long term goals? Start at the beginning of each day by listing what you need to accomplish (personal and work). Put them in order of importance. Complete the first task before you go to the second, and the second before you go to the third. If urgent enough, the bottom or least pressing, will eventually move up to the top. You can only put off your laundry for so long. Plan tasks that take more creativity or brainpower when you are at your best. Do not try to compose an important letter when you are half asleep. Some people are sharper early in the morning and others do not fully come awake until afternoon. Recreational Outlets: There are a number of things we cannot control in our lives, but having fun is not one of them. Everyone needs to find, and take time, to pursue leisure time activities. Playing cards, dinner with friends, basketball, or going to the movies may not make life’s problems go away, but they do provide a nice respite. Top tips to survive stress: Changing one's position more secure, and be prepared for changes to avoid stress and survive in the competitive world. Re-energize and re-motivate yourself. Spend quality time with your family. This can be an excellent source of emotional and moral support. Avoid using alcohol, smoking and other substance abuses Develop positive attitudes towards stressful situations in life. In case of chronic stress consult a health professional. Adapting to demands of stress also means changing your personality. Improve your line of communication, efficiency and learn from other's experiences. Breathing Exercise. Say kind ‘no’ to additional commitments or responsibilities Avoid trying to achieve too much Re-evaluate your goals and prioritize them Evaluate the demands placed on you and see how they fit in with your goals Identify your ability to meet these demands. Learn stress management skills Identify stressors in your life, get the support of your friends, family and even counseling in reducing stress Get adequate sleep and rest. Ensure that you are eating a healthy, balanced diet Try to recognize your spiritual stance and do meditation Proper Time Management To be more Organised and sense of control over the task which need to be fulfilled. Summary Stress, to a large extent, is under our control. Stress results from our appraisal of a situation and its demands, and our resources for coping with the situation. The key points can be summarized as follows (from Mind Tools, 1995): Short-term stress occurs when you find yourself under pressure in a particular situation. A certain level of short term stress is needed to feel alert and alive Too much is unpleasant and can seriously damage performance Short term stress is best handled using mental or physical stress management techniques Long-term stress comes from a buildup of stress over a long period. Sustained high levels can lead to and/or complicate serious physical and mental health problems if not controlled. Long-term stress is best managed by changes to lifestyle, attitude and environment. If people learn about and understand stress, they can take a proactive role in managing their stress and making it work for them - in college as well as in their future personal and professional lives. Most people know stress is a killer, but still do not follow through with the above recommendations. It thus takes time that is difficult to find in a busy schedule. It also entails making a deliberate choice to adopt constructive coping mechanisms rather than relying on those that we may have learned growing up. Virginia Satir, the family therapist, succinctly summarized the basis of stress management as follow: “Life is not the way it’s supposed to be. It’s the way it is. The way you cope with it is what makes the difference.” References Aherne, D. (2001). Understanding student stress: A qualitative approach. Irish Journal of Psychology, 22, 176 – 187. Baird, K. (2001). Attachment, coping, and satisfaction with life in an Irish university sample: An exploratory study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Georgia State University, U.S.A. Brotheridge, C. (2001). A comparison of alternative models of coping: Identifying relationships among co-worker support, workload, and emotional exhaustion in the workplace. International Journal of Stress Management, 8 (1), 1-14. Butler, G. & Hope, R.A. (1995). Manage your mind: The mental fitness guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Cohen, S. & Wills, T.A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310-357. Davis, M., Eshelman, E.R. & McKay, M. (1995). The relaxation and stress reduction workbook, 4th edition. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, Inc. Fisher, S. (1994). Stress in academic life: The mental assembly line. Buckingham, UK: Open University. Greenberg, J.S. (1987). Comprehensive stress management, 2nd edition. Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown Publishers. Lazarus, R.S. & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. Lopez, F.G. & Brennan, K.A. (2000). Dynamic processes underlying adult attachment organization: Toward an attachment theoretical perspective on the healthy and effective self. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 283-300. Lyubomirsky, S. (2001). Why are some people happier than others? The role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. American Psychologist, 56, 239-249. Mind Tools (1995). Effective Stress Management [online], Available: http://www.mindtools.com [March 3, 2001]). Student Health Centre (2001). Making stress work for you. Dublin: Trinity College. Tinto, V. (1998). College as communities: Taking research on student persistence seriously. Review of Higher Education, 21, 167-177. Tyrrell, J. (1993). Factors affecting student mental health. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Olpin, Michael. (2006). Stress assessment. Retrieved September 20, 2006, from Weber University: Health 1110 Stress Management http://faculty.weber.edu/molpin/healthclasses/1110/1110syllabus.html Appendix 1: Stress Management Pressure Cooker