Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality

advertisement

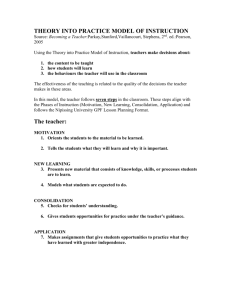

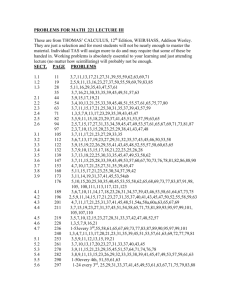

Curriculum Development: A Synthesis Deborah Davis Liberty University EDUC 871 Overview Developing, Implementing, and Evaluating Curriculum Approaches to Curriculum Development Implementation, Instruction, and Technology Evaluation and Assessment of Learning Approaches Purposes the school seeks Educational experiences Organization Evaluation Purposes Innovation Problem solving Love of learning Tools of analysis, expression, and understanding Roles Experiences and Organization Building consensus Selecting the best Preparing for the future Content and Performance Standards Content and Performance Standards Players and Methods Implementation & Instruction Curriculum and/or instruction Models and bases Technology Tech-savvy “digital natives” Creativity Differentiated learning Evaluation Formative and Summative Self-evaluation of teaching style Emerging Trends identify choose assess dig develop examine agree ask why Assessment Success in learning Differentiation of assessment methods Conclusion “To keep the curriculum engine running smoothly, regular tune-ups must be performed by highly trained personnel who can diagnose engine problems before they lead to actual breakdown” (Meyers, 2005/2014, p. 457). Questions? References Ametepee, L. K., Tchinsala, Y., & Agbeh, A. O. (2014). The no child left behind act, the common core state standards, and the school curriculum. Review Of Higher Education & Self-Learning, 7(25), 111-119. Ansary, T. (2014), The muddle machine: Confessions of a textbook editor. In F. Parkay, E. Anctil, & G. Hass (Eds.), Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality educational programs (pp. 340-345). New York: Pearson. (Reprinted from Edutopia 1(2). (Nov. 2004)). Boudett, K., Marnane, R., City, E., and Moody, L. (2014), Using student assessment data to improve instruction. In F. Parkay, E. Anctil, & G. Hass (Eds.), Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality educational programs (pp. 436-444). New York: Pearson. (Reprinted from Phi Delta Kappan 86(9). (May 2005)). Brown, L. (2014), The case for teacher-led school improvement. In F. Parkay, E. Anctil, & G. Hass (Eds.), Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality educational programs (pp. 346349). New York: Pearson. (Reprinted from Principal Magazine. (Apr 2008)). References (continued) Hass, G., (2014). Who should plan the curriculum? In F. Parkay, E. Anctil, & G. Hass (Eds.), Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality educational programs (pp. 313-316). New York: Pearson. (Reprinted from Educational Leadership 19(1). (Oct 1961)). Kempson, J. N. (2015). Star-crossed lovers: The department of education and the common core. Administrative Law Review, 67(3), 595-628. Maylone, N. (2014). TestThink?. In F. Parkay, E. Anctil, & G. Hass (Eds.), Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality educational programs (pp. 415-418). New York: Pearson. (Reprinted from Phi Delta Kappan 85(5). (Jan 2004)). Meyers, L. (2014).Time for a tune-up: Comprehensive curriculum evaluation. In F. Parkay, E. Anctil, & G. Hass (Eds.), Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality educational programs (pp. 453-457). New York: Pearson. (Reprinted from Principal Leadership 6(1). (2005)). References (continued) Miller, D. (2014). Assessing students with special needs in the general education classroom. In F. Parkay, E. Anctil, & G. Hass (Eds.), Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality educational programs (pp. 418-426). New York: Pearson. (Written for .), Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality educational programs. (10th Ed. 2014)). Parkay, F., Anctil, E., & Hass, G. (2014). Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality educational programs (Tenth ed.). New York: Pearson. Phillips, V. & Wong, C. (2014). Tying together the common core of standards, instruction, and assessments. In F. Parkay, E. Anctil, & G. Hass (Eds.), Curriculum leadership: Readings for developing quality educational programs (pp. 317-322). New York: Pearson. (Reprinted from Phi Delta Kappan19(5). (2010)). Ralph, B. W., Thomson, D. R., Cheyne, J. A., & Smilek, D. (2014). Media multitasking and failures of attention in everyday life. Psychological Research, 78(5), 661-669. doi:10.1007/s00426013-0523-7 Script notes 1 - During today’s presentation, Deborah Davis, who is working on her doctorate in Curriculum and Instruction at Liberty University, will present a synthesis on curriculum development. Thank you for your kind welcome. 2 - Let’s start with an overview. During today’s presentation, we will walk through the process of developing, implementing, and evaluating curriculum. This will include some of the approaches to curriculum development as well as the steps of implementation, instruction, technology, evaluation, and assessment. Our primary resource for today’s presentation is a work by Parkay, Anctil, and Hass (2014). 3 - Parkay, et al. (2014) reminded us, “Clearly there is no single right way to develop a curriculum” (p. 297). Further, Parkay et al (2014) cites the Tyler rationale, asking specifically about four issues: 1) the educational purposes; 2) the educational experiences that are likely to achieve those purposes; 3) the necessary organization of those experience; and 4) some method of evaluation to ensure purposes have been met. Script notes (continued) 4 - Within the Parkay et al (2014) text, there are a number of essays. One writer, Hass (1979/2014) presents that these elements are “The curriculum we need” (p. 313). And that there are roles for everyone engaged in the development process. Parents and other members of the community are and should be guiding forces for determining the direction of the curriculum -innovation. Scholars in various fields know the best methods for developing situations in which students will learn – problem solving. Students know whether or not the curriculum encourages them to learn and to love learning. Educators understand what is required to implement a curriculum, and can aid in developing tools that will enhance understanding and expression. As Hass (1979/2014) said, “Who should plan the curriculum? Everyone interested in the future . . . “ (p. 316). 5 - Nobody knows what happens in a classroom better than the teacher and students in that classroom. Consequently, while input from the students is important, input and engagement of teachers is critical. Brown (2008/2014) presents this notion as building “instructional capacity and instructional consensus among school staff” (p. 347). In embracing the construct that those most engaged know what is best, this does not limit design options to the staff at the school. Instead, it allows for community engagement on the highest order. Individuals, such as the Gabler’s in Texas who founded Educational Research Analysts, can direct the future of our curriculum through argument with textbook editors and the state review process (Ansary, 2004/2014). The key of improved curriculum is a willingness to be non-traditional, student-oriented, and careful reviewers of the voluminous data available (Brown, 2008/2014). Script notes (continued) 6 - The last piece in the approaches to curriculum segment deals with standards. The idea that someone out there in the big wide world, who frequently has no connection with day-to-day classroom activities is enough to make any educator cringe. The ideal of a common set of state standards to prepare all students equally for college-ready standards sounds like a wonderful ideal (Phillips & Wong, 2010/2014). The reality has been less than wonderful. Granted the goal of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) of 100% proficiency was unattainable, but the federal mandate for Common Core State Standards (CCSS) is certainly no less so (Kempson, 2015). Since before the days of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the government has been engaged in the educational process. Indeed, most state constitutions have a provision for compulsory education. On the face of it, governmental mandate to ensure children have a right to an educational base is decidedly favorable. As usual, however, the devil is in the details. Presumably, CCSS was written to “fully prepare students to compete successfully in the global economy” (Ametepee, Tchinsala, & Agbeh, 2014, p. 115). Of course, the details of CCSS are enough for a days-on-end conference, but suffice it to say, the idealized purpose is one to be embraced, but the methodology, time constraints, and engagement of boots-on-the-ground players leaves much to be desired. 7 - The differences between curriculum and instruction are noteworthy, though the two are not mutually exclusive. While curriculum provides what to teach, instruction is how to teach it (Parkay, et al., 2014). Any experienced or skilled educator knows that the models of teaching are not exclusive, but intertwined and invoked as needed for the enhanced skills of the student. Models also have bases: behavior psychology, Human development, cognitive processes, and social interaction (Parkay, et al., 2014). It can be said the educational purposes are met if the student understands the subject, can apply it to new issues, and wants to keep learning. Script notes (continued) 8 - This image, available at guide2digitallearning.com is also in Parkey, et al. (2014, p. 366). While it is difficult to view this way, I have included it because it is difficult. It represents the plethora of digital communities to which a student is likely connected. And this is just those related to the education of that student! The opportunities gained by the use of technology are plentiful. The challenge is to aid the student in finding the ones that work the way that student learns. While students today are considered to be “digital natives” because they were born into an age of digital media abutting their every nerve, it does not mean that they are truly tech savvy. Many of them know how to do most anything on their phones or game systems, but those skills do not always transfer into the classroom setting. A study by Ralph, Thompson, Cheyne, and Smilek (2013) finds that “media multitasking may be specifically related to problems in inattention” (p. 661). It isn’t that students have more or less cognitive understanding, it is that they are so used to the rapid fire engagement of their attention via the media that they do not know how to focus on one activity, thought, or need for an extended period of time. That said, the educator of these students must stay current on educational technology to engage the students and find their individual learning methods. This way, the students can be taught the way they can best learn. Script notes (continued) 9 - Evaluating curriculum is an ongoing process, or it should be. Those who use the curriculum should be consistently determining if it works, if it works well, or if it needs modification. Formative evaluation is the result of application. It allows an educator to determine if the curriculum provided what the students needed to learn. As a consequence, teachers may change they way they teach the curriculum. In summative evaluation, teachers are determining if the students are ready to move forward at the end of the term. If a thorough use of curriculum leads to an entire class ready or not ready to move forward, something can be presumed about that curriculum. Ongoing formative evaluation allows the teacher to evaluate personal teaching style. It presents a cognitive factor into what can become a rote method. Turning the method can throw off everyone in the classroom, and in doing so, can elicit a new excitement for learning the material. The cycle pictured here comes from Boudett, Murnane, City, and Moody (2005/2014) and represents an emerging trend in curriculum evaluation -- an improvement cycle: identify patterns in data gleaned from assessments; choose patterns to explore for areas of improvement; dig deeper into the data to assess problem areas; agree on a problem for action; ask why it is a problem; examine current practices in that area; develop an action plan to solve that problem; implement the action plan for that particular issue; assess the action plan for efficacy; and begin again on that problem or another. Script notes (continued) 10 - Assessment is more than just the test. Proper assessment allow “educational leaders to determine the degree to which curriculum goals are being attained . . . and to develop strategies for curriculum reform and improvement” (Parkay, et al., 2014, p. 403). Everyone values success, but everyone has a different definition of success. In a world where the monetary factor is overwhelming, sometimes it is hard to value success in the classroom as learning for the sake of learning. One way to engage students in the assessment process is to differentiate the assessment methods. While multiple choice may be easy to grade, written responses, portfolios, or project work may show more of the students’ understanding. One consequence of mandated assessment testing has been to lower the percentage required to pass (Parkay, et al., 2014). One solution is a greater emphasis on performance-based assessments. Maylone (2004/2014) presents that those who foist the standardized test requirements would be unwilling to take the tests themselves. Test anxiety is a very real factor and warrants consideration. Another very real factor is the inclusion of students with disabilities into the pool of test-takers. Some students with disabilities are high-functioning and with few accommodations can rank high within the standardized testing scales. Some, however, do not function in a manner that allows for such a measurement. As presented by Miller (2014/2014), “Specific assessments for students with disabilities as described in their IEP add another layer of complexity to the assessment picture” (p. 423). Script notes (continued) 11 - Curriculum development is not a straightforward issue. It is a winding path that branches in many directions. While it may seem direct or cyclical, it is not. Educators, however, in their many skills and facets, are the key to ensuring that the curriculum meets the needs of all those engaged, and that is everyone in the community. All told, the goal is met is the student understands the material, can apply it to new learning, and wants to learn more. 12 - Thank you so much for your attention. Are there any questions for me? Please note that my scripted references follow this slide and behind that is the script of this presentation.