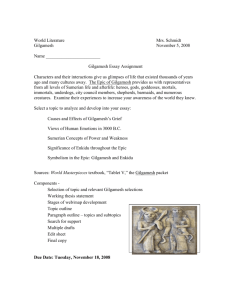

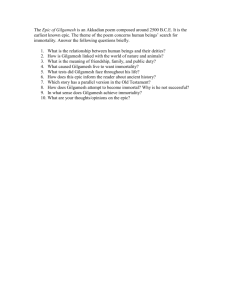

combined world literature essays and challenge essay

advertisement

COMBINED WORLD LITERATURE ESSAYS AND CHALLENGE ESSAY DO NOT COPY and or REPRODUCE ANY OF MY WORK IN ANY WAY! IT IS ALL COPYWRITTEN, STUDY, IT IS WORTH IT. Oliver Schbley Dr. Sheldon EN 560 26 September 2012 Gilgamesh and Odysseus: A Comparison of Heroes Over 1000 years and 1300 miles separate the epic heroes Gilgamesh and Odysseus; two distinct paragons of heroism and masculinity who each illuminate the similarities and differences between the two cultures that spawned their great epics. The ancient Sumerian tablets comprising The Epic of Gilgamesh depicts the ancient Mesopotamian culture and values through its hero Gilgamesh; a sharp contrast to the Greek Renaissance era Odysseus, the Hero of Homer’s The Odyssey. The Epic of Gilgamesh is the oldest example of epic poetry to survive to the modern era and as a result, Gilgamesh is the archetypal epic hero because of his divine heritage and inhuman perfection. Gilgamesh’s physical perfection is referenced several times throughout the poem, being described by the epic’s unknown narrator as: “Wild calf of Lugalbanda, Gilgamesh is perfect in strength, Suckling of the sublime wild cow, the woman Ninsun, Towering Gilgamesh in uncannily perfect.” (100) The portrayal of Gilgamesh’s perfect physical form should not overshadow his flawed personality; because the moral of this epic, acceptance of death and respect of the property of others’, is expressed via Gilgamesh’s metamorphosis from a deeply selfish demigod to a benevolent king, worthy of rule. Gilgamesh’s disrespect for personal property of his citizens, the brides of Uruk, culminates in a heroic showdown where Gilgamesh meets his partner Enkidu for the first time. Gilgamesh, up until this point, acts on impulse without any regard for others. Gilgamesh starts to enter a wedding, intending to defile a bride on her wedding night, until he is stopped by Enkidu: “Enkidu blocked the door to the wedding with his foot, not allowing Gilgamesh to enter.” (109) The fight between Enkidu and Gilgamesh results in mutual respect, friendship and a new, heroic Gilgamesh. Diverging from the traditional, godlike warrior-hero archetype of The Epic of Gilgamesh, Homer introduces and new kind of hero in The Odyssey. Odysseus stands out from the heroes of other epics, unique because of his humanity and morality. Unlike Gilgamesh and other heroes of epic poetry, Odysseus is completely human, with no divine ancestry. Odysseus’s mortality subjugates him to the whims of the gods like, Athena, Zeus and Poseidon as well as other mythical beings like Calypso and Polyphemus. Gilgamesh changes all that he encounters throughout his epic, whereas Odysseus must focus on survival, outwitting entities that are far more powerful than himself. This key divergence between the heroes of The Odyssey and The Epic of Gilgamesh illuminate the different intended audiences for each poem. Gilgamesh’s perfection, means and authority make him less relatable to modern audiences, with the message of The Epic of Gilgamesh demonstrating proper rule, and leadership. This can be compared to The Odyssey, whose human protagonist describes a value system where intelligence and prudence are paramount to strength and divinity. Taking pace after the events of the Iliad, The Odyssey is the story of Odysseus’s long return voyage home to Ithaca, following the Greek victory at Troy. Deciding Odysseus’s fate and fortune, the gods of The Odyssey play an instrumental role in the shaping of events. This contrasts to the gods of The Epic of Gilgamesh, who do foretell the future and exert control over Enkidu but do little to stop or hinder Gilgamesh. One example from The Odyssey of the direct divine intervention occurs when Odysseus is still trapped on Calypso’s island. Listening to the please of his daughter, Athena, Zeus sends Hermes, his herald, to Calypso’s island. Hermes is instructed to tell Calypso: “Zeus wants you to send him back home. Now. The man’s not fated to rot here far from his friends. It’s his destiny to see his dear ones again.” (387) This theme of divine intervention manifests itself repeatedly in The Odyssey, usually in the form of Athena granting aid to Odysseus. The several differences between The Odyssey and The Epic of Gilgamesh mentioned thus far are not surprising given the vast amount of space and time that separates these epics. However, what is, perhaps, surprising are the similarities between these two poems. One of the primary messages of The Odyssey is the importance of being a gracious host and curious guest. This theme is also present, to a lesser extent, in The Epic of Gilgamesh, where Gilgamesh learns to respect property following his fight with Enkidu. The other key similarity between these two texts is the importance of perseverance. Like Odysseus, Gilgamesh perseveres through many torments, battles and deaths. In conclusion, the characters of Odysseus and Gilgamesh epitomize two very different types of hero. The hero modeled by Gilgamesh makes use of his natural strength, his wealth and his ability to lead men and have men at his disposal to change the world, hopefully in a positive way. This hero seeks the simple goal of glory, achieving this though conquest and victory. The hero introduced by Homer in The Odyssey begins having already attained glory, a mortal man with wealth and happiness waiting for him back home. Homer’s hero does not seek to conquer, simply to return and who in spite of impossible odds does so, at great personal cost. Oliver Schbley Dr. Sheldon EN 560 10 December 2013 Modern Values Reflected in Story of the Western Wing Confucian thinking has been a part of Chinese Culture for much of recorded history and is the foundation of a culture that is based on civil duty and respect for one’s elders, and superiors. For thousands of years children, in China, have been raised according to Confucian principles, one of the most important of these being: Obeying the words and wisdom of parents and elders. The most beloved classic Chines stories reappear reinvented as old generations adapt them for new generations. “Story of the Western Wing” is Wang Shifu’s retelling of the cautionary tale of “The Story of Yingying,” which depicts two lovers who are each punished for acting against the words of their elders and defying Confucian principles of obedience and duty; only a few key differences change “Story of the Western Wing” into a more modern love story, ending with the two lovers being together. Confucianism is code of conduct that can be applied like a template to almost any religion or government. National pride culminating in civic duty, respectful obedience and careful well-planned lives are all encouraged under Confucianism and it is no coincidence that both “Story of the Western Wing” and “The Story of Yingying” feature elements of civic duty and parental obligation as their underlying morals. In the older tale of “The Story of Yingying” the shame suffered by Yingying as she is denied marriage by the man she gave her virginity to is designed to warn readers that succumbing to desire spoils one’s value as a wife and men should and do marry women with unspoiled values. Because “Story of the Western Wing” does not result in Zhang’s rejection of his beloved and his later regret, and Wang Shifu allows Zhang to look past older, more rigid traditions and fulfill his poetic promises of love and marriage. Wang Shifu’s alteration of the ending to this classic tale could likely invoke outrage from more traditional practitioners of Confucian doctrine who value duty and obedience above trivial, selfish loves. In order for Zhang and Yingying to be true adherents to Confucian ideals, they would not only have to subdue their lust until after marriage but also secure the blessing of their parents who, considering Zhang’s wealth and status, rejected their union in both stories. Both lovers defy their parents wishes and get married, ending “Story of The Western Wing” and after suffering as a result of breaking Confucian restraint, Zhang returns triumphant from his government examinations and, like in “The Story of Yingying,” finds his beloved already married. However, unlike the original, Wang Shifu then has Yingying secreted away to elope with Zhang, ending well after much suffering. Traditional observers of Confucianism may have certain issues with this happy ending, question if Wang Shifu altered or damaged the moral by including a happy ending. It could be argued that because Zhang is allowed to be with his lover is a reward for disobedience and lust. Another issue that could be raised is that a woman who gives into passion does not deserve a husband like Zhang, who successfully completed his tests and was about to begin a life of civil service. Alternatively, it could be seen that since Zhang had successfully completed his prior obligations of his test, he must then fulfill his obligations of returning to marry Yingying. Also, upon realizing that his “Oriole” was already married, Zhang’s despair and Yingying’s marriage to another could be seen as enough punishment and deterrent to future generations. Oriole is Zhang’s loving name for Yingying, meaning “little bird” this term of endearment is unlike the ironic nickname present in “The Story of Yingying” which hinted at a free-spirited girl who was free. Wang Shifu is counting on a more modern audience that implements Confucianism in their daily lives, but do not strictly adhere to the oldest beliefs and practices. Civil service, duty and respect for one’s elders are still paramount in Chinese culture, however, the cruelty of Zhang’s abandonment in “The Story of Yingying,” would likely overshadow its underlying principles of Confusion restraint. Instead, by allowing Zhang and Yingying’s love to flourish, he reintroduces a classic story to modern audiences with a taste for romance, and a preference for happy endings. The best stories are ones that can be easily compared to real life and the actions of characters determine whether that character is repeatable to the reader or not. As the expectations of society change so do the expectations of the reader and Wang Shifu alters “The Story of Yingying” just enough, so that Zhang and Yingying’s characters and voice are representative of the lives of today’s readers. Instead of prohibiting what kinds of women a man should marry, and what a woman must do to remain desirable, Wang Shifu builds the moral of the “Story of Western Wing” around duty, service and loyalty. Because of Zhang passing his government test, providing a means of sustenance via his state service, and fulfilling his obligations and promises by marrying Yingying, a woman he genuinely loved; Zhang represents a modern interpretation of Confucianism. Bibliography Puncher, Martin . The Norton Anthology World Literature, Volume 1. W.W. Norton & Company, print. The Longman Anthology of World Literature: The Medieval Era, Vol. B, Ed. David Damrosch, 2004. Oliver Schbley Dr. Sheldon EN 560 8 November 2013 Genji and Zhang The literature of medieval China and Japan share many of the same stylistic features; The Tale of Genji and “The Story of Yingying” both begin with flawed protagonists who, by the end of each of their stories, demonstrate integrity and virtu. filmmaker shooting a modern remake of Casablanca or some other equally well loved classic is not likely to be supported in his endeavor. Instead, this artistic reimagining, whether good or bad, would likely be condemned as a sort of artistic vandalism. This immediate dismissal of a reinvented story would not have occurred in Medieval China and Japan where good stories were tales that communicated clear moral messages which depicted individual acts of integrity. In both the medieval Japanese and Chinese cultures, true stories that describe life constantly evolve and retain specific archetypes resulting in stories that do not die alongside their creators but instead grow and contribute to generation after generation. What results from this process are stories that are immortal; relevant narratives that are still true to the original moral message. The protagonists of The Tale of Genji and “The Story of YingYing,” Genji and Zhang, are only able to effectively communicate their emotions via poetry. The stories’ systematic substitution of emotional dialogue and statements of yearning allows for honest exchanges between characters who desire to express love, anger and jealous rage but are limited to their own buddhist beliefs dissuading attachment and exalting consist integrity; the poetry within The Tale of Genji and “The Story of Yingying” allows for the characters of Gilgamesh and Zhang to remain true to buddhist ideals, serving as an example to future generations, however, divergence from these buddhist behavior codes cause the neglect, rejection and suffering of Yingying as well as the wives of Genji and their cruel treatments serves as a cautionary tale for future generations. The two poets behind the stories of Zhang and Genji, Yuan Zhen and Murasaki Shibuki, carefully weave together a collection of poems that form unique moral messages that are at the heart of each story. Zhang and Genji are two very different individuals who share little at the beginning of each story, with the exception of a common deficiency in buddhist sensibility. Zhang is introduced as a highly educated boy, ambitious and ready committed to a life of civil service. Unlike Genji, when Zhang is first presented with temptation, Yingying, he successfully adheres to the buddhist principles he came into the story knowing; this can be compared to Genji, who when first introduced as an adult, is completely ignorant of the obsession that will doom him to loss of love which delays his transformation into the wise, noble and much more influential Genji we are shown at the tale’s closure. Zhang and Genji’s restraint, political influence and personal attachment to temporary possessions culminate in different but complimentary aphorisms; restrained narration and muted description underlie principles of placing beauty or poetry high over the drugery and banality of suffering. The first indications of what is to become of Zhang and Yingying’s last night spent together is hinted at in a poetic passage describing the incipient doubt and anxiety forming in Zhang: “He ties a lover’s knot as sign their hearts are one … The sky is high and not easy to traverse, the morning cloud is nowhere to be found,” (1060) immediately Zhang and Yingying’s indiscretion settles in a bad way and festers inside Zhang’s mind, because the object of his desire weakened his resolve enough so that he willingly destroyed the one thing he found most beautiful in Yingying, honor and innocence impervious to the erosion of half-commuted suitors looking only to satisfy desire. Yingying, at first, presented herself in a proper way that fanned the flames of Zhang’s passion; however, her willingness to forsake her integrity for physical pleasure results in the two lovers sharing an ephemeral moment, destroying any chance they had for lifelong happiness. Like Genji, Zhang and Yingying move on in life, have children, start families and live lives that are simply less beautiful as consequence. Zhang’s story ends differently than Genji’s and emphasizes a warning intended for future seekers of love and happiness, suggesting that one must never let temptation, no matter how powerful, taint the morality of someone you find truly beautiful. The two poems are works of intensely dramatic narration accented with poems that express the true emotions, fears and obsessions frame The Tale of Genji and “The Story of Yingying" this shared aesthetic contrasts sharply with the stoic protagonists of the tale who adhere to many buddhist principles. Suffering, especially the suffering of women, is the most ubiquitous themes shared amongst these stories; however, the cause of this suffering does not remain the same and differs between the two stores in the same way that the two protagonists differ in their initial obsessions that lead the two men down different paths. The aesthetic of The Tale of Genji prioritizes subtly and much of the narrative’s meaning relies on careful reading; The moments immediately before the passing of Murasaki, Genji marvels at her beauty and does show legitimate concern; however it dwells on her fading beauty and apparent loneliness which is brief reminder of the narcissistic, possessive Genji. The following passage reflects this mental state before Murasaki’s death as well as illustrates the distance created by the descriptive narrative and the emotional verse: “Despite the fact that she was terribly emaciated … for just as dawn approached, she passed away,” (1267) perfectly encapsulates the very moment that Genji shed his covetous obsessions at the same time ridding himself of the source of suffering which has plagued him ever since he lost his mother at the threshold of childhood. The moment of Genji’s spiritual transformation is the same moment that his cherished Murasaki dies: “Genji suffered the most … His son looked on in sympathy, thinking his father’s grief was perfectly understandable,” (1268) finally worn down by years of disciplined neglect. Genji’s life concludes at the apex of his spiritual progression when, after years of suffering caused by his own overIndulgences, he frees himself of his maternal obsession and decides to allow his bride, Murasaki, to become a nun; this final progression pushes Genji beyond his unwillingness to let go of worldly connections but it is too late and Genji has lost yet another love in a hard-learned lesson that young adults all over the world have learned and will continue to learn from as they figure out that attachments to things long past and obsessions over what is not in our control waste life diminish its beauty. Working together, these Medieval Chinese and Japanese poetic narratives deliver combined messages which reaffirms one truth, forcing its readers to introspect on their own lives, expectations and unhealthy infatuations: The Tale of Genji and “The Story of Yingying’s” poetry exist to remind us that our spiritual happiness and fulfillment depend on life long efforts to suppress attachment control emotion, and remain respectful and respected. Work Cited Puncher, Martin . The Norton Anthology World Literature, Volume 1. W.W. Norton & Company, print.