Keeping Households Out of Trouble

advertisement

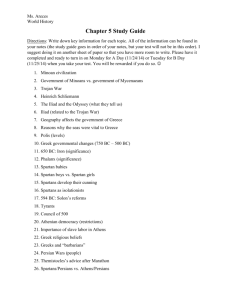

Keeping Households Out of Financial Trouble A Public Lecture Sponsored by the Ramon Areces Foundation and IE Michael Haliassos Goethe University Frankfurt, CFS, CEPR, NETSPAR • Shiller: “The basic mission of finance is to set up arrangements whereby people may pursue risky opportunities without themselves being destroyed by this risk, and arrangements that incentivize people to behave in a socially constructive manner.” in Haliassos (ed.), Financial Innovation: Too Much or Too Little? MIT Press 2013 • My talk: Based on recent household finance research, - Ways in which households may get into financial trouble - Research and policy challenges in trying to avert trouble through • Financial literacy initiatives • Regulation • Legal framework • Transparency and financial advice • Harmonization of institutions and policies 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 2 Recent Work I will Draw On • Haliassos, M. (ed.), Financial Innovation and Economic Crisis, MIT Press, 2013 [Contributors: Ackermann, Barberis, Campbell, Case, Greenwood, Issing, Shiller, Shleifer, Smets, Smith, Vassalou, Viceira] • Georgarakos, Haliassos, Pasini, “Household Debt and Social Interactions”, forthcoming in the Review of Financial Studies. • Christelis, Georgarakos, Haliassos, “Differences in Portfolios Across Countries: Economic Environment versus Household Characteristics”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 2013. • Bilias, Georgarakos, Haliassos, “Portfolio Inertia and Stock Market Fluctuations”, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 2010 • Fuchs-Schuendeln and Haliassos, “The Role of Product Familiarity in Household Financial Behavior”, Working Paper, 2014 (on SSRN) • Haliassos, Jansson, Karabulut: “Incompatible Partners? Cultural Predispositions and Household Financial Behavior”, Working Paper, 2014. 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 3 Financial Innovation: Providing Opportunities • Plenty of opportunities for use of innovative (but information intensive) products: - Accumulating for old age: e.g. individual retirement accounts - Saving on interest costs: refinancing opportunities - Handling longevity risk: (deferred) annuities - Handling inflation risk: e.g. indexed bonds - Handling house price risk: e.g. home equity insurance plans or index-based and cash-settled futures and options (e.g., with reference to C-S index) 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 4 Getting into trouble • Being forced to make decisions you cannot handle - Demographic transition • Being enticed to use financial products you do not understand - Misselling due to conflict of interest - Underestimating risks, exaggerating potential benefits • Being tempted to mimic peers with higher means and/or better knowledge • Conforming to (negative) cultural prototypes in financial behavior • Key potential drivers: • Financial illiteracy • Lack of familiarity with certain financial products • Bad financial advice and limited transparency • Negative influence of social interactions • Persistent influence of slow-moving cultural factors 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 5 Financial Literacy • There is ample evidence that financial illiteracy is present and disproportionately so for certain demographic groups, across a wide spectrum of countries. • For example, Lusardi and Mitchell (2006) showed that: • only 18% of US households aged 51-56 could calculate two-year interest compounding correctly • of the rest, only 43% simply failed to compound interest • Particularly acute problem in certain education and race groups • Question: Does financial illiteracy cause bad financial outcomes? 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 6 Financial Literacy (ctd) • Tests: Regress outcomes on measures of financial literacy today - A number of authors have found that poor outcomes (lower wealth, limited stock market participation, lack of retirement planning, use of higher cost credit, being in credit arrears) are correlated with limited basic financial literacy, or advanced financial literacy (e.g., Alessie, Lusardi, Van Rooij, JFE; Disney and Gathergood, 2011). • Crucial problem: potential for reverse causality or unobserved heterogeneity • Best reaction so far: look for good instruments by going back in time - Early life conditions - Education of parents - Academic scores (e.g. in math) at age of 10 or prior to entering economic life - Exogenous changes in academic requirements for youngsters • Important problems: - Is it the only channel of influence? - What is the time dimension of the effect? 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 7 Familiarity with the Financial Product • Key tension: - Widespread financial illiteracy, especially among disadvantaged groups - Financial innovation, producing complicated products • Regulatory response: - Require familiarity checks (e.g., MIFID) - Ban sales of certain products (e.g., Belgian ban on structured products) • Implicit assumption: - Lack of familiarity with a financial product encourages participation and this channel can be effectively countered or stopped through regulation • Observations: - Lack of familiarity could discourage participation: e.g., skiing! - Lack of familiarity could be offset through other channels (info, advice) 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 8 A potential test for the role of familiarity and its problems • Ideally, we would like to test for an effect of familiarity on participation, controlling for household characteristics and for social comparison effects • Problems: - How to measure familiarity on a wide range of households and products - Reverse causality: participation causes familiarity - Unobserved heterogeneity: hidden factors affect both without a direct link between them 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 9 Our Approach Fuchs-Schuendeln and Haliassos (2014) • Large field ‘experiment’: German reunification - • East Germans exogenously deprived of ‘capitalist’ financial products Then, exogenously provided the same opportunity to use them as West Entire population, variation in characteristics Genuine financial instruments: securities, consumer debt, life insurance Variation in the degree to which instruments were familiar to the East Potentially large stakes (‘making it’ in the unified country) Micro-data from the German Socioeconomic Panel (GSOEP): 1991-2009 - - 27.1.14 If lack of familiarity acted as an inhibiting factor, we would expect: • Smaller use of capitalist products by East Germans, at least initially • Gradual convergence to participation rates of West Germans, controlling for characteristics, as familiarity grows If lack of familiarity caused over-participation and regret, we would expect subsequent drops in participation Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 10 Results: Documenting West-East Differences in Participation Rates 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 11 Results: Documenting West-East Differences in Participation Rates 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 12 Participation in products familiar to East Germans: Savings Accounts 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 13 Participation in products familiar to East Germans: Life Insurance 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 14 Controlling for Household Characteristics • Using counterfactual analysis, we decompose observed differences in participation rates into two components: - One due to differences in the overall configuration of observable characteristics between East and West Germans - The other, reflecting differences in participation rates among East and West Germans that share similar observable characteristics • What could differences in financial behavior among similar households be reflecting other than differences in familiarity? - Differences in culture (unlikely for East and West Germans) - Differences in institutional environment (but they live in the same country) - Discrimination against East Germans, but: • Not supposed to happen • No evidence of this • The pattern of results we get is not consistent with discrimination 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 15 Controls • • • • • • • • • • • gender dummy age categories: 20-34, 35-49, 50-64, 65 and above marital status: single, married and divorced household composition: number of adults and number of children educational attainment: at most general elementary schooling, completed high school, and completed college labor force status: retired, unemployed, not in labor force, apprentice occupation: self employed, blue collar, white collar in financial sector, white collar in non-financial sector, and civil servant household monthly net income homeownership two proxies for consumer sentiment: being concerned about - general economic development - own economic prospects Decompositions robust to controlling for (perfect foresight) income expectations and peer income 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 16 Consumer credit: East Germans are more likely owners than similar West Germans 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 17 Securities: East Germans behave like comparable West Germans! • Familiar Products: Savings Accounts and Life Insurance - East Germans are more likely to participate initially but gradually observed participation rates converge - This conclusion applies also when we control for characteristics 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 18 Conclusions on Familiarity • In the face of major opportunities and social comparisons, lack of familiarity does not seem to - discourage entry - or delay it - or encourage unwarranted entry (at least as indicated by subsequent exit) • Our results are consistent with the literature on: - Familiarity and local bias - Financial product awareness (Guiso and Jappelli, 2005) • Unlikely that familiarity test is the relevant aspect for regulators to focus on • Even a financial literacy test may not be sufficient! - Financial literacy correlates positively with overconfidence and large risk exposures • Campbell, Calvet, Sodini, JPE: bigger return shortfalls among the literate, despite higher Sharpe ratio 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 19 The Value of Financial Advice • • The principle of the good car mechanic Problems: - How much does the advisor know? • Dates back to Cowles (1933) • Bergstresser, Chalmers, Tufano (RFS 2009): Funds offered through brokers offer inferior returns to those sold directly - Do the sick go to the doctor? - e.g., Overconfident? Recall discount brokerage data set - Hackethal, Haliassos, Jappelli (2012): The richer, more experienced tend to be matched with advisors - Bhattacharya, Hackethal, Kaesler, Loos, Meyer (2012) • Random offer of unbiased financial advice to clients of a German brokerage • Only 5% accepted the offer of free advice; these tended to be male, older, wealthier, more financially sophisticated. • Those who needed the advice most were least likely to accept it 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 20 Financial Advice (ctd) • If households do go to advisors: - Are they helped in their actual account performance? • Hackethal, Haliassos, Jappelli (2012): - Advised accounts offer on average lower net returns and inferior risk-return tradeoffs (Sharpe ratios). - Role of incentives: Results apply with stronger force to BFA than IFA • What type of advice is actually given to households? - Mullainathan, Noeth, Schoar (2011): • Mystery shoppers with different ‘script’ initial portfolios sent to financial advisors for first visit (only). • Advisors show dramatic bias towards active management than towards index funds • Strong evidence of catering to initial portfolio, but also of reversals of advice in the course of the visit • Main problem: only first visit! 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 21 (Bad) Influence of Social Interactions: Peer effects on household consumption and financial behavior - Consumption: The Joneses just got richer and you haven’t (Kuhn, Kooreman, Soetevent, Kapteyn, 2011) - Consumption: The Joneses are poor, you look like them, and you want to signal otherwise (Charles, Hurst, Roussanov, 2009) - Asset: The Joneses hold risky assets and you follow their example (Duflo and Saez, 2002; Kaustia and Knüpfer, 2011) - Asset: You bump into the Joneses a lot and they talk about stocks (Hong, Kubik and Stein, 2004) - Debt: You perceive the Joneses as richer than you and you borrow, partly to fit in (Georgarakos, Haliassos, Pasini, 2013) 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 22 Household Debt and Social Interactions Georgarakos, Haliassos, Pasini (forthcoming in RFS) • Data: DBN Survey - Long panel, data from 1993 until 2009 (we use 2001-2008) • Central bank questionnaire: rich income and assets sections - Consumer loans: private loans, extended lines of credit, credit card debt, debt on banking accounts - Collateralized loans: mortgages on any piece of real estate, outstanding debts on hire-purchase contracts, debts based on payment by installment and/or equity-based loans; debts with mail-order firms, shops or other sorts of retail business 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 23 Why Dutch Data? • Difficult issue: Who is in the social circle? • Particularly acute for financial data: anonymization • Typical solutions: - Construct a social circle, based on households of similar age and education - Consider a very specific group and product: e.g., librarians and retirement plans - Or confine attention to the intensity of meetings with members of the social circle: • e.g., membership of social clubs, church-going, frequency of visiting neighbors • Our data: - Representative of the entire (Dutch) population - Respondents are asked directly about characteristics of their social circle 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 24 DNB Dutch Household Survey • Respondents report perceived characteristics of their “circle of acquaintances, that is, the people with whom you associate frequently, such as friends, neighbors, acquaintances, or maybe people at work”: - age category most of them belong to (perceived) average household income (in brackets) average household size average education most prevalent kind of employment (i.e. whether they are employed, selfemployed or in other conditions) - average hours of work per week, distinguished by gender. 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 25 Central Findings • Both prevalence of borrowing (informal, formal consumer loans, formal collateralized loans) and conditional amounts are boosted by average perceived income of acquaintances (self-reported in the DNB Survey) - The influence of perceived income is significant among those who perceive their income as below average for their social circle. • Significant effect of perceived relative standing also on indicators of overindebtedness, such as loan-to-value ratios, debt service ratios • Note: - Higher borrowing does not necessarily imply financial distress, delinquency or default - However, we did find effects on potential financial distress • So, even if borrowing is ex ante justified, it could turn out suboptimal ex post • Problem could arise for various income groups, not only the poor 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 26 Policy Implications • A Big Brother? • Rather: influence the link between observation of peer income and decision to borrow: - financial education - proper advice - transparency in marketing of financial products 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 27 The Effect of Cultural Predispositions on Household Financial Behavior Haliassos, Jansson, Karabulut (2014) • Questions - What is the role of culture in financial behavior, as distinct from institutions and policies? - Can we influence cultural predispositions by harmonizing institutions, as in the current EU experiment? • Starting point: International differences in household financial behavior - Substantial international differences in asset and debt holdings controlling for household characteristics (Christelis, Georgarakos, Haliassos, REStat 2013), attributable to the “economic environment” - Which part of this has to do with the “formal” constraints versus the “informal constraints” (North, 1990), or “cultural baggage” (Alesina and Giuliano, 2011) or set of beliefs, perceptions, ideas and collective experiences with institutions that constitute a people’s culture (Fernandez and Fogli, 2006)? 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 28 Modeling the Effect of Culture on Economic Outcomes • Following the Guiso-Sapienza-Zingales (JEP 2006) framework: - Distinguish between slow-moving and fast-moving aspects of culture: • Slow: religion and ethnicity • Fast: social interaction effects - The channel: • From: religion and ethnicity • To: - beliefs (priors) and preferences Trust Risk aversion Thriftiness - political and institutional outcomes • To: - 27.1.14 economic outcomes Asset participation Debt participation National saving rates Other topics… Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 29 Methodological concerns with existing literature • Culture may affect economic outcome via different channels - E.g., trust - Risk aversion - Degree of patience • Exploiting ethnic origin or variation in a particular home country characteristic to uncover its effect on an economic outcome in the host country: - Researchers impose equality of all other coefficients across people of different cultures • Regressing behavior in the host country on average behavior in the home country (e.g. Fernandez and Fogli, Kountouris and Remoundou) - There should be no unobserved factors that correlate to behavior in the home country and to behavior in the host country: • e.g. internet infrastructure and stock market participation - Remaining coefficients on characteristics should be the same for immigrants and natives 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 30 Our Approach • • • • Consider immigrants to a single country (Sweden) to remove differences in formal institutions and policies Divide up European countries into “culture” groups - In a number of different ways, to examine robustness Derive differences in financial behavior between immigrants from each group and Swedish households - Participation in stockholding (except in retirement accounts), debt (except student loans), homeownership - Estimate the part of these differences that is NOT due to differences in relevant household characteristics, and trace it over the sample period 19992007 (decompositions based on counterfactual analysis) • Examine whether it simply reflects different experience of the groups with Swedish institutions • Examine whether it simply reflects discrimination against foreigners Persistence: Investigate whether the differences are amenable to influence by exposure to domestic institutions - Length of time in the country - Age at immigration: exposure to home-country institutions 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 31 Our Data • Longitudinal Individual Database (LINDA) - Observation period from 1999 to 2007 - LINDA consists of an annual cross-sectional sample of around 300,000 individuals, or approximately 3% of the entire Swedish population, and an annual immigration sample of around 200,000 individuals, or approximately 20% of all immigrants in Sweden. An individual is included in the immigrant sample if he/she was born outside Sweden. - Restrict attention only to those households that existed for the entire sample period, and where the head remained the same - We exclude from the sample household heads under 18 years and households with annual disposable household income less than 10,000 SEK - Native: if the household head and the spouse (if any) are born in Sweden and both have Swedish citizenships - Immigrant: If the household head was born outside Sweden (in a European country) 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 32 Our Data • Survey data provided by FSI (org., Forskningsgruppen för Samhälls- och Informationsstudier) - Survey conducted every year on a representative sample of Swedish inhabitants from different municipalities over the period from 2000 to 2008 - Questions to capture the attitudes of respondents about immigrants • "Do you think that Sweden should continue taking in immigrants/refugees to the same extent as now?” - We use the share of people in the province answering "To a lesser extent” - About 55% on average, with 11% non-response 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 33 Coming up with Country Groups • Approach 1: Use genetic distance as a measure of closeness in the past - Consider genetic distance of each country to Sweden - Consider genetic distance more generally • Across any pair of countries • Using the dominant population in the country or population weights • Construct dendrograms and use two alternative grouping methods - “ruler” versus “consistency” method - Show that all these alternatives yield a consistent country grouping • Approach 2: Use the Hofstede (1980) “cultural dimensions”: - Power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance - Build a score using principal component analysis and classify countries according to this. 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 34 Country Groups based on (Dominant) Genetic Distance 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 35 Country Groups based on Hofstede Cultural Dimensions 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 36 Stockownership: With or Without Control for Attitudes Towards Immigrants 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 37 Debt Outstanding: With or Without Control for attitudes towards immigrants 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 38 Stockownership: Newcomers versus old-timers/horizon 0.45 0.4 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 Balkan long BALFIN short 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 BALFIN long SUFI long SUFI short 0.45 0.4 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 Northern long Northern short 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 0.45 0.4 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 2000 1999 Balkan short 0.45 0.4 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 Turkey short 2001 RIP short Turkey long 2000 RIP long 0.45 0.4 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 1999 0.45 0.4 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 Stockownership: Exposure to Home Institutions/Choice BALFIN late 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 Northern early Northern late 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 SUFI late BALFIN early 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 SUFI early 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 -0.05 RIP early RIP late 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 -0.05 Turkey early Turkey late 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 -0.05 Balkan late 2000 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 -0.05 Balkan early 1999 0.35 0.3 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 -0.05 Stockownership: Head has Swedish Citizenship 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 41 Conclusions on Importance of Cultural Predispositions • PIIGS are not all the same • When confronted with different institutions, little evidence that PIIGS exhibit the same patterns as in the home country/original institutions • PIIGS seem to learn from other PIIGS more experienced with the new institutions and converge to their types of behavior • Convergence and assimilation to the new institutions takes time and is being shown only for cases in which citizens accept the new institutions 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 42 Regulating Household Access: Financial products as medicines? • Lots of common elements: - Could be dangerous when administered to the wrong people - Could be lethal when taken in large doses - Could be prescribed to the wrong people by incompetent or irresponsible doctors - Producers may find it optimal to standardize and popularize their innovations, so as to operate in a lower-cost, wider-access environment • A medical solution: - Product-based • Ban lethal or generally harmful medicines • Set up FDA to test products and make sure they are safe - User-based • Make sure they are only given to the “right” patients - Practitioner-based • Sold only by responsible pharmacists • Require prescriptions • Fight conflict of interest of doctors: - Hippocratic oath - Malpractice suits 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 43 Difficulties with Product-based Access Regulation • Very difficult to predict how a particular financial product will actually be used - Theory-based optimal use of an instrument does not reveal how it will actually be used • Securitization of mortgages and their breakdown into different risk classes that could be disseminated to those willing to take risks was theoretically sound - Seeing how an instrument was used in the past does not reveal how it will be used in the future • The precursors of asset-backed securities were German covered bonds, which effectively survived for 300 years or so - Seeing how an instrument is being used in one type of account is not informative on how it will be used in a different location (account), even by the same people! - Seeing that people own a particular type of account/instrument (e.g. brokerage account/stocks) may not be revealing of their overall tendency to get into trouble (contrast with Vissing Jorgensen and consumer products) 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 44 Should we restrict access to stocks because some households overtrade? PSID Data Source: Bilias, Georgarakos, Haliassos (JMCB, 2010) 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 45 Are brokerage account owners different? Source: Bilias, Georgarakos, Haliassos (JMCB, 2010) 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 46 Is stock overtrading, even in brokerage accounts, “lethal”? Source: Bilias, Georgarakos, Haliassos (JMCB, 2010) 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 47 Concluding Remarks: How to Protect Households from Financial Trouble? • Financial literacy or familiarity tests may not achieve the desired objectives and may actually inhibit financial literacy, familiarity, and financial innovation • Promoting transparent products, default options, targeted financial advice, (early) financial education, and product awareness may be the better ways to protect households from financial trouble • Improving and harmonizing institutions seems to influence financial behavior despite the presence of slow-moving cultural predispositions • Developing a legal framework for investor and borrower protection seems important to deal with failures 27.1.14 Haliassos, Ramon Areces Foundation Lecture 48