Lecture 17

advertisement

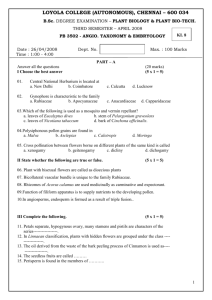

BIOLOGY 3404F EVOLUTION OF PLANTS Fall 2008 Lecture 17 Thursday November 20, 2008 Chapters 19 & 20, parts Angiosperm life cycle and flowers Angiosperm life cycle • Similar to gymnosperms, EXCEPT that the nuclear state of the developing ovule is much more complex: • 2n meiosis n mitosis 8 haploid nuclei (1 egg, 2 synergids, 3 antipodals, 2 polar nuclei) • Double fertilization: 2 sperm nuclei involved, one fertilizing the egg ( 2n zygote) and one uniting with the 2 polar nuclei ( 3n endosperm) [other patterns exist, as in lilies] • Food reserves of gymnosperm seeds are haploid (megagametophyte tissues); in angiosperms, they are triploid (endosperm) [5n in lilies] Corn seed, with lots of endosperm Seed of a eu-dicot, shepherd’s purse, with very little endosperm Angiosperm flowers • Floral diversity is the hallmark of the angiosperms: how we recognize them and how they find (or are found) and recognize each other for mating purposes • Selective forces for pollination, protection from predation, and eventual dispersal of seeds or fruits have shaped flowers and inflorescences A honeybee on Lemna (larger ovals) and two species of Wolffia (the smaller ones) (Fig. 21-2a). These are the smallest flowering plants. Wolffia borealis: whole flowering plant is less than 1 mm long Lemna gibba: flowering plant with two stamens and one style Coconut palm, Cocos nucifera Flowers and fruits of banana (Musa x paradisiaca) Rice (Oryza sativa) Saguaro cactus in flower An orchid flower (Cattleya) An orchid flower (l) compared to a radially symmetrical flower (r) Parts of a lily flower Hepatica americana (Ranunculaceae, a basal eudicot) California poppies Types of inflorescences (arrangements of flowers). I Types of inflorescences (arrangements of flowers). II Types of inflorescences (arrangements of flowers). III Types of inflorescences (arrangements of flowers). IV Shooting star (Dodecatheon) Butter-and-eggs (Linaria vulgaris) Lupine (Lupinus) Mertensia Water hemlock (Cicuta maculata) A catkin, of birch (Betulaceae) Staminate catkins and acorns of tanbark oak (Lithocarpus) Flowers of many grasses, including corn (Zea mays), are windpollinated. Staminate flowers (left) and ovulate flowers (right) Stigma Stamens Inflorescences of Elymus (= Agropyron) a grass related to wheat A grass spikelet, a cluster of florets. Spikelets may be arranged in a variety of inflorescence types (see slide #25) An individual grass floret dissected out of a spikelet The grass floret dissected still further, to show the androecium and gynoecium Ray flowers Disk flowers A typical inflorescence of a composite (Asteraceae) Composite inflorescence and flowers dissected and explained Not all composites have disk flowers Thistles have only disk flowers Positioning of the ovary within a flower, from ancestral (left) to derived (right) Placentation, the arrangement of ovules within the ovary Dodder (Cuscuta), a parasitic plant in the Convolulaceae Rafflesia, the world’s largest flower, is parasitic on roots of Vitaceae Indian-pipe (Monotropa uniflora) is a parasite on ectomycorrhizal fungi that tap sugars from nearby photosynthetic host plants Flowers and fruits of Magnolia grandiflora, a woody magnoliid Flowers of Aristolochia grandiflora, a paleoherb Rhizanthella, a mycoheterotrophic orchid that grows underground Flowers of Rhizanthella exposed The vanilla orchid; hand pollination to insure good yield of pods Longhorn beetle pollinating a lily; inset, beetle fossil of 95-98 MYA Beetle pollinators that are pollen-feeding (left, on Hepatica, Ranunculaceae) or nectar-drinking (right, on Angophora, Myrtaceae) Fly-pollinated flowers are often dark reddish, and stinky, like this South African succulent Stapelia schinzii (Asclepidaceae) Honey bee pollinating rosemary (Rosemarinus officinalis, Lamiaceae) A sweat bee pollinating a cactus flower Foxglove (Digitalis, Scrophulariaceae) has a landing pad and “honey guides” for bee pollinators Marsh marigold (Caltha palustris, Ranunculaceae): what WE see Marsh marigold (Caltha palustris, Ranunculaceae): what BEES see A bumblebee in a California poppy (Eschscholzia californica, Papaveraceae) The “bee orchid” (Ophrys speculum, Orchidaceae) flower looks so much like a female bee that male bees try to mate with it; in doing so they get hit on the head or back with a pollensac, or pollinium, which they carry to the next flower A fly-pollinated orchid (Piperia elegans, Orchidaceae, left), and a mosquito carrying a dumbbellshaped pollinium on its head (below) A fly on a camas lily (Zygadenus) with bright yellow nectaries Many butterflies and moths are pollinators, and drink nectar through their long proboscis (arrow) A yucca moth on a Yucca flower (Asparagaceae); larval moths eat some of the seeds in the resulting yucca fruit Bird-pollinated flowers are often red; those pollinated by hummingbirds usually have a long corolla tube with nectaries at the bottom. Note anthers dusting the bird’s forehead with pollen. A sunbird (Anthreptes) at a bird-of-paradise flower (Strelitzia, Strelitziaceae). Sunbirds are regarded as important pollinators, but this one appears to be taking the “nectar thief” shortcut through the bottom of the flower. The nectar of these columbine flowers is only (?) available to birds Poinsettias (Euphorbia pulcherrima, Euphorbiaceae) are pollinated by birds, but ants like the nectar, too. A lesser long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris curasoae) getting a faceful of pollen at a cactus flower at night. Threadlike pollen of the sea-nymph (Amphibolis, Cymodoceaceae, Alismatales) trapped on the forked stigma. Whereas most aquatic plants actually have aerial flowers and “normal” pollination, those whose pollination is truly aquatic often have filamentous pollen. Staminate flowers (left) of the freshwater eel-grass (Valisneria, Hydrocharitaceae) are produced underwater, then are released to float to the surface. There, they drift into depressions formed by the larger pistillate flowers, which remain attached to the plant. Pollinators and floral diversity • Plants with catkins (slides 34 and 35) are mostly wind-pollinated, as are the grasses and most gymnosperms. • Were pollinators the only forces shaping flowers through evolutionary history? See the paper by Brown (2002), linked on the web site.