St Marks-Pattabi-Kim-Neg-PESH-Round3

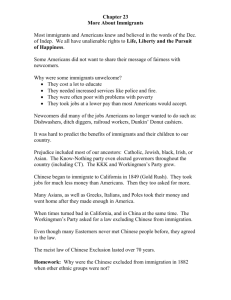

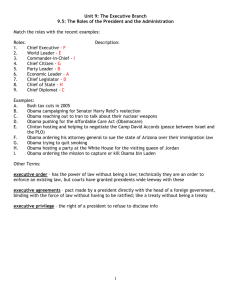

advertisement