HO 25 - CalSWEC

advertisement

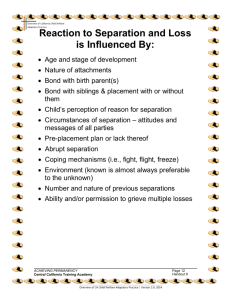

A Psychosocial Model of Adoption Adjustment1 Infancy (Birth to 12 Months) Erickson’s Psychosocial Tasks: Trust vs. M istrust Adjusting to transition to a new home. o Infant Responses to a New Home. (Birth to 4 weeks) Little distress seen. Newborns are focused on having body needs met and not attentive to surroundings. (4-12 weeks) Much distress seen. Infants can respond to new stimuli in the environment, but cannot shut it out when it becomes too much. (12-24 weeks) Little distress seen. Babies can respond to more complex stimuli, modify it as needed, and adjust better to changes in diet and environment. - (6-12 months) Much distress seen. Babies are grieving for loss of the primary caretaker to whom attachment is intense at this age. o Developing secure attachments, especially in cases of delayed placement. Developmental Effects of Parental Separation/Loss Short-term effects of parental separation/loss o Grief is shown through a regression in dependency (withdrawal, sleeping or eating problems, uncontrollable crying, etc.) o Child’s sense of security and trust for adult availability is undermined. o Interruption in the acquisition of basic cause and effect understanding because of changes in daily routine that accompany changes in caretakers. Possible long-term effects of the loss o If dependency needs are not met, child expects that life owes him. o Difficulty ever meeting dependency needs of others. o Poor trust. o If cause and effect not addressed, learning problems seen at the 4–6 grade level. Minimizing the effects of the loss o Ensuring that new caretakers are available “on demand” for the infant. o Gearing all interactions to “What will help this infant learn to trust that adults will be available?” o Transferring routines to the new family setting. o Following a consistent routine. 1 Brodzinsky, David; Schechter, Marshall; and Marantz, Robin. Being Adopted: The Lifelong Search For Self, Doubleday, 1992. Enita KearnsHout, Consultant/Trainer, February, 2000 (Developed for The Adoption Exchange, Denver, Colorado). Adapted from Fahlberg, Vera I., A Child’s Journey Through Placement. Perspectives Press, 1991. Adapted by Laura Williams, June 2002. ACHIEVING PERMANENCY Central California Training Academy Page 8 Handout 8 Toddlerhood and Preschool (Age 12 Months to 5 Years) Developmental Effects of Parental Separation/Loss Erickson’s Psychosocial Tasks: Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt and Initiative vs. Guilt Placement-Related Tasks Need to understand that they were first born to birth parents who could not take care of them. Learning about birth and reproduction. o Around Age 4, beginning to understand: Time and space. That things happened in the past about which they have no memory. The concept that they may someday be a mom or dad. Ask questions about growing inside “your tummy.” Adjusting to initial information about placement. Enjoy hearing their story told to them; Encourage caretakers parents to start talking to children about placement now. Recognizing differences in physical appearance, especially in interracial placement; Do not really comprehend how these differences came about. ACHIEVING PERMANENCY Central California Training Academy Toddler Years (1–3) Short-term effects of parental separation/loss Disruption of balance between age-appropriate dependency and independence Interference in the child’s sense of self (changes in first name during this period of ego development may be particularly harmful) Decreased awareness of both external and internal stimuli Regression in terms of most recently acquired skills Temporary interruption of language acquisition Possible long-term effects of the loss Permanent disruption in balance between dependency and independence; child may grow up to be “victim” or “victimizer.” Permanent disruption in ego development may result in development of “borderline personality.” A lack of awareness of internal discomfort (that is, knowing when hungry or full, not being aware of physical pain, and so forth). Long-term subtle language problems. As adults, problems with being rigid, inflexible, and unable to deal with aggressive impulses. Long-term problems with interpersonal relationships. Minimizing the effects of the loss Preparing for moves Paying careful attention to meeting child’s dependency needs while helping child feel more adequate Allowing regression to earlier levels of functioning Pre-School Years (3–6) Short-term effects of parental separation/loss Magical thinking about the loss. Child’s perception that s/he is “bad.” Long-range effects of the loss Child’s belief that s/he does not deserve to have good things happen. Child’s persistence in misbehaving. Problems with sexual identity if the child thinks the loss was a result of his desiring the parent of the opposite sex all to him/herself. Difficulty taking responsibility for his own behavior. Need for external controls. Difficulty taking nurturing or enjoying the pleasures of childhood. Focus on control issues. Minimizing the effects of the loss Identifying, clarifying, and remediating the magical thinking (particularly important) Providing adequate opportunities for play (for reduction of loss) Page 9 Handout 8 Middle Childhood (Early Stage – Ages 6 to 8 Years), (Later Stage – Ages 9 to 12 Years) Erickson’s Psychosocial Tasks: Industry vs. Inferiority Experts consider this a good time for adoptive children to have contact with the birth family if available. By age 6, understanding reproduction – can differentiate between being born and being adopted. Understanding the meaning and implications of being placed; begin to see “being placed/adopted” as a negative. o Coping with peer reactions to placement; want to “belong” and do not like feeling different due to being placed/adopted; may resist talking about placement/adoption. o Coping with stigma associated with placement/adoption. By age 7 or 8, comparing himself to others – can understand “blood relations” and that his family is different than that of most other children. o Coping with physical differences from family members. Expressing anger, hurt and sadness about abandonment – coming to grips with the reality that to be chosen, first you have to be “un-chosen” – feeling unlovable, unwanted and unworthy. o Searching for answers regarding origins and reasons for the placement/adoption – interested in details like if were birth parents married or had other children. o Begin internal search for answers; may begin to question choices that birth parents made (i.e., if she didn’t have enough money, why didn’t she get a job?) o Feeling guilty about what they did that lead to not being kept by birth parents. o Problem behaviors may appear as they struggle to cope with feelings of grief and loss. May begin to develop “family romance fantasy” (i.e., I must belong to a richer, kinder, family); difficult to resolve as, unlike birth kids, they DO have another family out there somewhere. Until age 10 or 11, not fully understanding the legal system – think birth parents can reclaim them. Feeling confused about their feelings as they are developing the ability to think without using words. ACHIEVING PERMANENCY Central California Training Academy Developmental Effects of Parental Separation/Loss Short-term effects of parental separation/loss o Less energy for tasks o Decreased academic performance o Decreased energy for peer relationships o Confusion about “right” and “wrong” Possible long-term effects of the loss o Long-term problems in either schooling or peer relationships o Problems with internalization of conscience o Focus on control issues Minimizing the effects of the loss o Providing child with opportunities to focus on grieving o Identifying values as “this is the way we do it in our family,” rather than implying that other values are wrong Page 10 Handout 8 Developmental Effects of Parental Separation/Loss Adolescence (Ages 13 to 18) Erickson’s Psychosocial Tasks: Ego Identity vs. Identity Confusion Further exploration of the meaning and implications of being adopted; may want to know more details of how they came to be available for adoption; it’s important to be truthful with teens. Coping with adoption-related loss on a deeper level, especially as it relates to the sense of self. Working to connect “being adopted” to one’s sense of identity (i.e., Who am I in relation to my birth family? In relation to my adoptive family?) Coping with differences from family of origin. o Wanting more details about birth parent’s physical appearance. o Coping with racial identity (in cases of interracial adoption), physical differences and birth parent characteristics; may “try on” birth parent attributes (i.e., promiscuity, drug use, etc.) to see if that’s a part of who they are. o Tending to guard thoughts and not share questions about their origins with parents. Working to resolve the family romance fantasy. Considering the possibility of searching for biological family; may not openly engage adoptive parents in this step of the search process; important for adoptive parents to know though that the questions are being asked internally; encourage adoptive parents to look for opportunities to open the discussion about adoption (i.e., movies, news articles, etc.) Not uncommon for adopted teens, particularly those with history of abuse & neglect, to be placed in out-of-home care for a period of time; encourage adoptive parents to stay connected and work to create lifelong relationships for the teen. Looking at the original adoption plan in the context of simple solutions. Short-term effect of parental separation/loss o Interruption in tasks of psychological separation from parent figures who are consistent in their availability and behaviors Possible long-term effects of the loss o Adolescent becoming suicidal or acting out in a variety of antisocial ways if he believes he has lost all control over his life o Adolescent becoming totally dependent on peers to meet all of his need for approval if a family doesn’t meet his needs o Focus on control issues Minimizing the effects of the loss o Providing numerous opportunities for children to have control over other aspects of their lives o Making children an integral part of decision making for their futures o Providing stable adult role models Young Adulthood Erickson’s Psychosocial Tasks: Intimacy vs. Isolation Further exploration of the implications of adoption as it relates to the growth of self and the development of intimacy. Further considerations of searching and/or beginning the search. Adjusting to parenthood in light of the history of one’s relinquishment. Facing one’s unknown genetic history in the context of the birth of children. Coping with adoption-related loss. ACHIEVING PERMANENCY Central California Training Academy Page 11 Handout 8