Language Development: Differences

advertisement

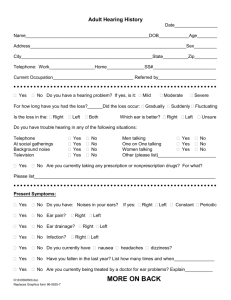

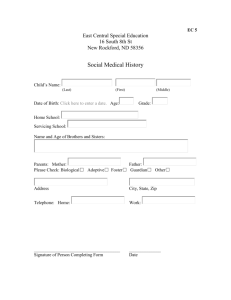

Language Development: Differences EDU 280 Fall 2014 Standard English Language of elementary schools and textbooks Language of the majority of the people in the U.S. Dialect A variety of spoken language unique to a geographic area or social group May include phonological or sound variations, syntactical variations, and lexical, or vocabulary variations Categories: Regional & geographic Social and ethnic Black English Ebonics a nonstandard form of English A dialect often called Black English Characterized by not conjugating the verb “to be” and by dropping some final consonants from words Black English Second Language Learners 2 categories Children who came to this country at a very young age or are born here to immigrants who have lived in areas if the world where culture, systems of government and social structures differ from those in the U.S. Native born Native Americans Alaskan natves Second Language Learners Bilingual learner English as a second language student Students with limited English proficiency Language-minority learner English language learner Linguistically diverse student Second Language Learners Simultaneous Bilingualism A child younger than 3 years of age who learns two (sometimes more) languages at the same time Sequential Bilingualism a child who learns a second language after the age of 3 Children with Special Needs Hearing Disorders Characterized by the inability to hear sounds clearly May range from hearing speech sounds faintly or in a distorted way to profound deafness Speech-Language Disorders Communication disorders that affect the way people talk and understand Range from simple sound substitutions to not being able to use speech and language at all Speech-Language Disorders Non-organic causes lack of stimulation lack of need to talk poor speech models lack of or low reinforcement insecurity, anxiety, crisis Language Delay Characterized by a marked slowness in the development of the vocabulary and grammar necessary for expressing and understanding thoughts and ideas (NAHSA, 1985). May involve both comprehension and the child's expressive language output and quality. Language Delay A complete study of a child includes first looking for physical causes, particularly hearing loss, and other structural (voice producing) conditions. Neurological limitations come under scrutiny, as do emotional development factors. Home environments and parental communicating styles are examined when a thorough study by speech-language pathologists takes place. Referral to experts is considered if a child falls two years behind his or her peers or when a sudden change in a well progressing child is noticed. Language Delay Dumtschin (1988) has identified possible noticeable behavior of language-delayed children: limited vocabularies use short, simple sentences make many grammatical errors may have difficulty maintaining a conversation talk more about the present and less about the future have difficulty in understanding others and in making themselves understood Articulation Articulation disorders involve difficulties with the way sounds are formed and strung together, usually characterized by substituting one sound for another, omitting a sound, or distorting a sound. If consonant sounds are misarticulated, they may occur in the initial (beginning), medial (middle), or ending positions in words. Normally developing children don't master the articulation of all consonants until age seven or eight. Articulation Most young children (three to five years old) hesitate, repeat, and re-form words as they speak. Imperfections occur for several reasons: A child does not pay attention as closely as an adult, especially to certain high-frequency consonant sounds The child may not be able to distinguish some sounds; a child's coordination and control of his or her articulatory mechanisms may not be perfected. For example, he or she may be able to hear the difference between Sue and shoe but cannot pronounce them differently. About 60% of all children with diagnosed articulation problems are boys (Rubin, 1982). Articulation characteristics of young children include: Substitution. One sound is substituted for another, as in "wabbit" for rabbit or "thun" for sun. Omission. The speaker leaves out a sound that should be articulated. He or she says "at" for hat, "ca" for cat, "icky" for sticky, "probly" for probably. The left out sound may be at the beginning, middle, or end of a word. Distortion. A sound is said inaccurately but is similar to the intended sound. Articulation characteristics of young children include: Addition. The speaker adds a sound, as in "li-it-tle" for little and "muv-va-ver" for mother. Transposition. The position of sounds in words is switched, as in "hangerber" for hamburger and "aminal" for animal. Lisp. The s, z, sh, th, ch, and j sounds are distorted. There are from 2 to 10 types of lisps noted by speech experts. Causes of Articulation Disorders Physical conditions Problems in the mouth Cleft palate Hearing loss Dental abnormality Faulty learning of speech sounds Voice Disorders Pitch Loudness Resonance Quality (hoarseness, etc) Fluency Disorders Stuttering Involves the rhythm of speech Characterized by abnormal stoppages with no sound Repetitions Prolonged sounds or syllables May be unusual facial or body movements Involves 4 times as many males as females Cluttering Involves the rate of speaking and includes errors in articulation, stress and pausing Speech seems too fast with syllables running together Fluency Disorders Cluttering Involves the rate of speaking and includes errors in articulation, stress and pausing Speech seems too fast with syllables running together Normal Dysfluency Approximately 25% of all children go through a stage of development during which they stutter. Selective Mutism Children who can speak but don't. May display functional speech in selected settings (usually at home) and/or choose to speak only with certain individuals (often siblings or same-language speakers). Researchers believe selective mutism, if it happens, commonly occurs between ages 3 and 5 years. Hearing A screening of young children's auditory acuity may uncover hearing loss. The seriousness of the problem is related both to the degree of loss and the range of sound frequencies that are most affected (Harris, 1990). The earlier the diagnosis, the more effective the treatment. Since young children develop ear infections frequently, schools alert parents when a child's listening behavior seems newly impaired. Otitis media Any inflammation of the middle ear. Many preschoolers have ear infections during preschool years, and many children have clear fluid in the middle ear that goes undetected (NAHSA, 1985). Even though the hearing loss caused by otitis media may be small and temporary, it may have a serious effect on speech and language learning for a preschool child. Diagnosing an Ear Infection Anatomy of the Ear Ear Tube Otitis media If undetected hearing distortion or loss lasts for a long period, the child can fall behind. Signs General inattentiveness, wanting to get close to hear, having trouble with directions, irritability, or pulling and rubbing the ear Hearing Impairments Preschool staff members who notice children who confuse words with similar sounds may the the first to suspect auditory perception difficulties or mild to moderate hearing loss. Mild hearing impairment may masquerade as: • stubbornness • lack of interest • a learning disability. With intermittent deafness, children may have difficulty comprehending oral language. Severe impairment impedes language development and is easier to detect than the far more subtle signs of mild loss. Advanced Language Achievement Each child is unique. Teachers will encounter young children with advanced language development. A few children speak clearly and use long, complex, adult like speech at two, three, or four years of age. They express ideas originally and excitedly, enjoying individual and group discussions. Advanced Language Achievement Some may read simple primers (or other books) along with classroom word labels. Activities that are commonly used with kindergarten or first-grade children may interest them. Just as there is no stereotypical average child, language talented children are also unique individuals. Inferring these language precocious children are also intellectually gifted isn't at issue here. They may exhibit many of the following characteristics. Attend to tasks in a persistent manner for long periods of time. Focus deeply or submerge themselves in what they are doing. Speak maturely and use a larger-than-usual vocabulary. Show a searching, exploring curiosity. Ask questions that go beyond immediate happenings. Demonstrate avid interest in words, alphabet letters, numbers, or writing tools. Remember small details of past experiences and compare them with present happenings. Read books (or words) by memorizing pictures or words. Rapidly acquire English skills, if bilingual, when exposed to a language-rich environment. Tell elaborate stories. Show a mature or unusual sense of humor for age (Kitano, 1982). Possess an exceptional memory. Exhibit high concentration. Show attention to detail and a rich imagination. Possess a sense of wonder. Problems in communication skills for children ages 6 to 12 years may include: Hearing difficulties Difficulty with attention, following complex/compound directions in the classroom Difficulty retaining information Poor vocabulary acquisition Difficulties with grammar and syntax Problems in communication skills for children ages 6 to 12 years may include Difficulties with organization of expressive language or with narrative discourse Difficulties with academic achievement, reading, and writing Unclear speech Persistent stuttering or a lisp Problems in communication skills for children ages 6 to 12 years may include Voice-quality abnormalities, such as a strained, hoarse quality (may require a medical examination by an otolaryngologist [an ear, nose and throat specialist]) These communication problems can be helped by medical professionals, such as speech pathologists, therapists or the child's doctor.