Lecture 12 - Conversation analysis

advertisement

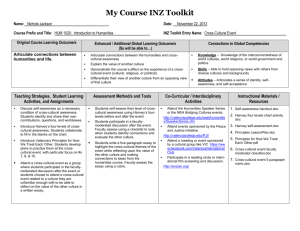

LING 122: ENGLISH AS A WORLD LANGUAGE -14 VARIETIES OF ENGLISH: Conversational Interaction Readings: Kachru & Smith, Ch. 8 Talk Shows from Around the World Note the similarities and differences in such conversational features as turn-taking, backchanneling, simultaneous talk, gestures, eye-gaze, etc. among the talk shows in … Japanese Thai Mexican Philippino Vietnamese Chinese The Structure of Conversation in Outer and Expanding Circle Contexts Required Concepts Interactive acts – how the interaction is managed Speech acts – what is being conveyed or negotiated between participants Crosscultural Differences Speech acts Cooperative principle Politeness Interactive Acts Turn-taking: the pattern of conversation in which one person speaks, then another Normally in SAE one person speaks at a time End of talk is signaled by Intonation, expressions like ‘you know,’ gesture, lengthening of final syllable, stressed syllable, etc. Floor: the right to begin to talk Has some duration Is topic-related Specific devices to gain or hold the floow and to control the topic Backchanneling: cues that signal attention and encourage the speaker to continue Simultaneous Talk: talk by more than one person over an extended period Crosscultural Differences Turns ‘Turn’ refers to the opportunity to assume the role of speaker and what is said by the speaker In some speech communities (e.g., Hindi, Japanese, Middle East, Eastern Europe) the onespeaker-at-a-time rule doesn’t apply Crosscultural Differences – Floor ‘Floor’ refers to the right to make a first statement during a conversation A: Did you hear the news? B: What? A: Bill is back in town! Who is/are controlling attention in conversation Who is/are controlling the topic of conversation Who is/are the central figure[s] in the conversation Crosscultural Differences – Floor In SAE Men are more successful in initiating and maintaining topics and tend to demand the floor more frequently In India Older participants have the right to initiate conversation, maintain the floow and yield the floor In traditional Western Europe Children are admonished to be seen, not heard In many other cultures Only older males initiate, maintain and control the floor Crosscultural Differences – Backchannel The frequency and duration of backchannnelling behavior varies from culture to culture Japanese speakers Use more frequent backchannel cues and the cues are of longer duration Speakers of languages that are socialized in the patterns of providing frequent and longer backchannel cues may use the same strategy in English This may be disconcerting to the Inner circle English speaker Crosscultural Differences – Simultaneous Talk ‘Simultaneous talk’ is normally considered rude in Inner Circle speech communities Rhythmic coordination –patterning of speech and non-verbal body movements Sync talk – overlapping speech & synchronized head nods, both postures High involvement style vs. high considerateness style FitzGerald’s 6 Styles of Interaction Institutional/exacting (Northern and Western Europe) Individual autonomy, non-imposition, brevity, explicitness, linearity, goal oriented Spontaneous/argumentative (Eastern Europe) Sincerity, spontaneity, closeness, blunt, direct Involved/expressive (Southern Europe, Latin America) Warmth, emotion, expressive, concern with according positive face to others, affective and contextual, tolerates overlap, collaborative rather than competitive FitzGerald’s 6 Styles of Interaction Elaborate/dramatic (Middle Eastern) Harmonious relations, positive face, affective contextual style stressing form over content, sweeping (over)generalizations, expressive metaphors Bureaucratic/contextualized (South Asian) Harmonious relations, positive face, affective contextual style stressing form over content, formal bureaucratic language, inductive organization Succinct/subdued (East & Southeast Asian) Harmony, modesty, conformity, positive face, masking negative emotions, status oriented, deferential How do FitzGerald’s six styles of interaction accord with the distinction seen in the video “Culturally Speaking: High Context - Low Context”? How do FitzGerald’s six styles of interaction accord with your own experiences? Crosscultural Differences – Rhetorical Strategies ‘Rhetorical strategies’ refers to how what one says is organized. Chinese professionals often first provide background info (history), then transition to main point (How do you decide what topic to research?) Because now, things have changed. It’s different from the past. In the past, we emphasized how to solve practical problems. Nutritionists must know how to solve some deficiency diseases. In our country, we have some nutritional diseases. But now it is important that we must do some basic research. So, we must take into account fundamental problems. We must concentrate our research to study some fundamental research. Indian English Often expresses direct disagreement, followed by backing down A: So in your family were you treated differently from your brothers in other ways? B: No, not in other ways, but yeah yes I was. They didn’t allow me. Crosscultural Differences – Rhetorical Strategies Signals of in-group membership Maori: R: Tikitiki, well we’re across the river from there and N: ae. R: If we wanted to go to Tikitiki we had to go right around to Ruatoria. And that was in winter. N: in winter eh. Malay: Eh Mala, where on earth you went ah? I searching, searching all over the place for you – no sign til one o’clock, so I pun got hungry, I went for makan. Implications for Crosscultural Conversations It is difficult to train people to change their patterns of synchronized, harmonious conversational interaction. But it is possible to Sensitize people to observe and minimize conditions that lead to a sense of discomfort in verbal interactions. Accommodate different rhetorical strategies in crosscultural communication Speech Acts By uttering a string of meaningful sounds, we perform not only the act of speaking, but also a variety of acts such as informing, questioning, ordering, etc., via the act of speaking. Open the door! Why are you frowning? Would you mind closing the door? The formula for finding the area of a circle is Πr². Speech Acts There is no set of speech acts and no set of strategies for performing speech acts such that all languages and cultures share them Example: saugandh khaanaa – Hindi for ‘to swear’ Doesn’t carry negative meanings Can swear by anything valuable ‘…and Ramu,’ she cried desperately, ‘I have enough of quarrelling all the time. In the name of our holy mother, can’t you leave me alone!’ Speech Acts Speech acts are interpretable only in the context of a society or culture Indian languages: Elders may bless a child instead of saying ‘thank you’ for rendering a service. Taiwanese Mandarin: uses a more direct strategy for making requests than SAE Igbo: Silence is the appropriate way to express sympathy to the bereaved following a death. The Cooperative Principle & Implicature: A. "Is that the phone?" "I'm in the tub." B. "Uncle Charlie is coming over for dinner." "Better lock up the liquor." C. "Do you know where Bill moved?" "Somewhere on the east coast." D."How was your blind date?" "He had a nice pair of shoes." E. "Professor Smith is sure he'll get tenure." "And my pet turtle is sure it will win the Kentucky Derby." Grice’s Cooperative Principle To describe in a systematic and consistent way how implicature works in conversation, Grice proposed the cooperative principle: In conversations, participants cooperate with each other. They do this by observing the conversational maxims. Grice’s Four Conversational Maxims Quantity - contribution should be as informative as required Quality - contribution should not be false Relation - contribution should be relevant Manner - contribution should be direct Assumptions: 1. We don't adhere to them strictly. 2. We interpret what we hear as if what we hear conforms to them. 3. Where maxim is violated, we draw implicatures. Violations Quantity Letter of reference: Bob speaks perfect English; he doesn't smoke in the office; and I have never heard him use foul language. Quality "Reno is the capital of Nevada, isn't it?" "Yeah, and London is the capital of New Jersey." Relation "What time is it?" "Well, the paper's already come." Manner "Let's stop and get something to eat." "OK, but not at M-c-D-o-n-a-l-d-s." Practice What maxim is violated? What is the implicature raised? 1. "How did Jeff do on the test?" "Well, he wrote something down for every question.“ 2. "Do you know where Bill is?" "Well, he didn't meet me for lunch like he was supposed to." Implicature Across Cultures Inner Circle Englishes value the Maxim of Quantity Speak directly to the point Long pauses are seen as disagreement or hostility Japanese English – Employs much longer pauses than SAE South Asian English – Silence on the part of the younger person is seen as agreement or acceptance. Politeness Face – the public self-image that every person wants to claim for him/herself. Negative face – the basic claim to freedom of action and freedom from imposition Positive face – the positive consistent self-image or ‘personality’ claimed by the person Threats to Negative Face Could you lend me a hundred dollars for a couple of days? Imposing a request If I were you, I would consult a doctor as soon as possible. That cough sounds dangerous to me. Offering a suggestion You are so lucky to have such good friends all over the world! Compliments (envy) Threats to Positive Face Weren’t you supposed to compete the report by now? Mild criticism I am not sure I agree with your interpretation of the by-laws. Disagreements One girl friend to another) Mabel thinks you have put on some weight. Bad news (shows the speaker not adverse to causing distress to addressee.) Crosscultural Takes of ‘Face’ Japanese culture values group harmony over individual rights Positive face considerations play a greater role in determining politeness than negative face considerations. Taiwanese culture prefers strategies like: I don’t like your performance; I am not pleased with your performance; I am not satisfied with your performance Rather than the preferred SAE strategies: I am concerned about your performance; I have been extremely concerned about your work performance lately; I don’t feel that you’re working to your full potential. Conclusions Communicative success depends on various aspects of conversational interaction. Content – speech acts, conversational maxims, politeness strategies Organization – turn-taking, maintaining the floor, backchannelling, simultaneous talk Languages and varieties differ with respect to how these aspects of content and organization are valued and realized in day-to-day interactions.