Reading Literature Strand CCSS Key Ideas and Details

advertisement

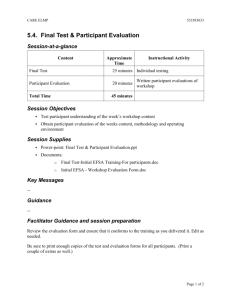

Reading Literature Participant’s Manual Day 4 CLASS Comprehensive Literacy for Adolescent Student Success CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 1 CLASS Homework Reflection Days 1-3 Name:_____________________________________________________________________________ Email Address: __________________________________________________________________ 1 a. What tool did you use to gather information about your students? Attach a copy of a completed tool with the student’s name removed. 2 a. What data did you use from the tool to inform your choice of text? 2 b. Did you use the data to select a text for whole class, small group, or an individual? 3. What text did you select? How does this text meet the needs of your students as identified by the data you collected? 4. If you have taught the text, how successful was the learning when you used this text to teach the standards? How did you assess the learning? 5. After reflecting on this process, what would you do differently next time? CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 2 Text Complexity and Alignment Analysis Qualitative Measures Notes Levels of Meaning or Purpose Single Level of Meaning---Multiple Levels of Meaning Explicitly stated purpose---Implicit purpose, may be hidden or obscure Structure Simple---Complex Explicit--- Implicit Conventional---Unconventional Events related in chronological order---Events related out of chronological order (chiefly literary texts) Traits of a common genre or subgenre—Traits specific to a particular discipline (chiefly informational texts) Simple graphics---Sophisticated graphics Graphics unnecessary or merely supplementary to understanding the text---Graphics essential to understanding the text and may provide information not otherwise conveyed in the text Language Conventionality and Clarity Literal---Figurative or ironic Clear---Ambiguous or purposefully misleading Contemporary, familiar---Archaic or otherwise unfamiliar Conversational---General academic and domain-specific Knowledge Demands: Life Experiences (literary texts) Simple theme---Complex or sophisticated themes Single themes---Multiple themes Common, everyday experiences or clearly fantastical situations---Experiences distinctly different from one’s own Single perspective---Multiple perspectives Perspective(s) like one’s own---Perspective(s) unlike or in opposition to one’s own Knowledge Demands: Cultural/Literary Knowledge (chiefly literary texts) Everyday knowledge and familiarity with genre conventions required---Cultural and literary knowledge useful Low intertextuality (few if any references/allusions to other texts)---High intertextuality (many references/allusions to other texts) Knowledge Demands: Content/Discipline Knowledge (chiefly informational texts) Everyday knowledge and familiarity with genre conventions required---Extensive, perhaps specialized discipline-specific content knowledge required Low intertextuality (few if any references to/citations of other texts)---High intertextuality (many references to/citations of other texts) CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 3 Quantitative Measures Notes Readability Measurement Reader and Task Considerations Notes Cognitive Capabilities o attention, memory, critical analytic ability, inferencing, visualization Motivation o a purpose for reading o interest in content o self-efficacy as a reader Knowledge o vocabulary and topic knowledge o linguistic and discourse knowledge o knowledge of comprehension strategies Experiences Task related variables Reader’s Purpose o Might shift over the course of reading o Type of reading Skimming Getting the GIST Studying Reading the text with the intent of retaining the information for a period of time Intended outcome An increase in knowledge A solution to some real-world problem Engagement with the text Alignment to the Standards Reading Strand Writing Strand Speaking and Listening Strand Language Strand Interdisciplinary Connections Social Studies Science Math Music Visual Arts Other CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 4 Reading Literature Strand CCSS Key Ideas and Details College and Career Readiness (CCR) Anchor Standard 1: Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. Grade Grade-Specific Standard With prompting and support, ask and answer questions about key details Kindergarten in a text. Grade 1 Ask and answer questions about key details in a text. Ask and answer such questions as who, what, where, when, why, and how Grade 2 to demonstrate understanding of key details in a text. Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, Grade 3 referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers. Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says Grade 4 explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly Grade 5 and when drawing inferences from the text. Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as Grade 6 well as inferences drawn from the text. Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis of what the text Grade 7 says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what Grade 8 the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the Grade 9-10 text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the Grade 11-CCR text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain. CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 5 Reading Literature Strand CCSS Key Ideas and Details CCR Anchor Standard 2: Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. Grade Grade-Specific Standard Kindergarten With prompting and support, retell familiar stories, including key details. Retell stories, including key details, and demonstrate understanding of their Grade 1 central message or lesson. Recount stories, including fables and folktales from diverse cultures, and Grade 2 determine their central message, lesson, or moral. Recount stories, including fables, folktales, and myths from diverse cultures; Grade 3 determine the central message, lesson, or moral and explain how it is conveyed through key details in the text. Determine a theme of a story, drama, or poem from details in the text; summarize Grade 4 the text. Determine a theme of a story, drama, or poem from details in the text, including Grade 5 how characters in a story or drama respond to challenges or how the speaker in a poem reflects upon a topic; summarize the text. Determine a theme or central idea of a text and how it is conveyed through Grade 6 particular details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments. Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the Grade 7 course of the text; provide an objective summary of the text. Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the Grade 8 course of the text, including its relationship to the characters, setting, and plot; provide an objective summary of the text. Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze in detail its development Grade 9-10 over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details; provide an objective summary of the text. Determine two or more themes or central ideas of a text and analyze their Grade 11development over the course of the text, including how they interact and build on CCR one another to produce a complex account; provide an objective summary of the text. CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 6 Reading Literature Strand CCSS Key Ideas and Details CCR Anchor Standard 3: Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text. Grade Grade-Specific Standard With prompting and support, identify characters, settings, and major events in a Kindergarten story. Grade 1 Describe characters, settings, and major events in a story, using key details. Grade 2 Describe how characters in a story respond to major events and challenges. Describe characters in a story (e.g., their traits, motivations, or feelings) and Grade 3 explain how their actions contribute to the sequence of events. Describe in depth a character, setting, or event in a story or drama, drawing on Grade 4 specific details in the text (e.g., a character’s thoughts, words, or actions). Compare and contrast two or more characters, settings, or events in a story or Grade 5 drama, drawing on specific details in the text (e.g., how characters interact). Describe how a particular story’s or drama’s plot unfolds in a series of episodes Grade 6 as well as how the characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. Analyze how particular elements of a story or drama interact (e.g., how setting Grade 7 shapes the characters or plot). Analyze how particular lines of dialogue or incidents in a story or drama propel Grade 8 the action, reveal aspects of a character, or provoke a decision. Analyze how complex characters (e.g., those with multiple or conflicting Grade 9-10 motivations) develop over the course of a text, interact with other characters, and advance the plot or develop the theme. Analyze the impact of the author’s choices regarding how to develop and relate Grade 11elements of a story or drama (e.g., where a story is set, how the action is ordered, CCR how the characters are introduced and developed). CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 7 Use this model to show how to use a longer text such as a novel or a play and select shorter complementary texts from different genres, cultures, and time periods that surround the same theme to deepen understanding. If one time period, culture, or century is represented in a unit, the next unit should be from another to provide the range required by the CCSS. Text Matrix: Fiction/Nonfiction Author Nathaniel Hawthorne Title Genre The Scarlet Letter Fiction: Novel CCSS Appendix B P. 145 Arthur Miller The Crucible Screenplay by Michael Sloane; Directed by Frank Darabont; Starring Jim Carrey The Majestic Movie (Clip of the HCUA Hearing) Robert Frost Emily Dickinson ?? The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA) (1938– 1975) “Nothing Gold Can Stay” “We Grow Accustomed to the Dark” CCSS Appendix B p. 119 History Textbook Drama Culture Century Early Written American/Puritan (1850)/Setting Mid-seventeenth Century New England American/Puritan Written (1952)/Setting (1692-1693) Province of Massachusetts Bay Century New England American/WWII Written (2001)/ Setting WWII America Nonfiction: Transcripts American (1938-1975) Poetry American Written (1923) Poetry American Written (1890) Nonfiction: Information about the Puritans American Current CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 8 CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 9 CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 10 (Example from Socratic Circles by Matt Copeland) CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 11 (Example from Socratic Circles by Matt Copeland) CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 12 Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Scarlet Letter: A Romance. New York: Penguin, 2003. (1850) From Chapter 16 The road, after the two wayfarers had crossed from the Peninsula to the mainland, was no other than a foot-path. It straggled onward into the mystery of the primeval forest. This hemmed it in so narrowly, and stood so black and dense on either side, and disclosed such imperfect glimpses of the sky above, that, to Hester’s mind, it imaged not amiss the moral wilderness in which she had so long been wandering. The day was chill and sombre. Overhead was a gray expanse of cloud, slightly stirred, however, by a breeze; so that a gleam of flickering sunshine might now and then be seen at its solitary play along the path. This flitting cheerfulness was always at the further extremity of some long vista through the forest. The sportive sunlight--feebly sportive, at best, in the predominant pensiveness of the day and scene--withdrew itself as they came nigh, and left the spots where it had danced the drearier, because they had hoped to find them bright. “Mother,” said little Pearl, “the sunshine does not love you. It runs away and hides itself, because it is afraid of something on your bosom. Now, see! There it is, playing a good way off. Stand you here, and let me run and catch it. I am but a child. It will not flee from me--for I wear nothing on my bosom yet!” “Nor ever will, my child, I hope,” said Hester. “And why not, mother?” asked Pearl, stopping short, just at the beginning of her race. “Will not it come of its own accord when I am a woman grown?” “Run away, child,” answered her mother, “and catch the sunshine. It will soon be gone. “ Pearl set forth at a great pace, and as Hester smiled to perceive, did actually catch the sunshine, and stood laughing in the midst of it, all brightened by its splendor, and scintillating with the vivacity excited by rapid motion. The light lingered about the lonely child, as if glad of such a playmate, until her mother had drawn almost nigh enough to step into the magic circle too. CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 13 “It will go now,” said Pearl, shaking her head. “See!” answered Hester, smiling; “now I can stretch out my hand and grasp some of it.” As she attempted to do so, the sunshine vanished; or, to judge from the bright expression that was dancing on Pearl’s features, her mother could have fancied that the child had absorbed it into herself, and would give it forth again, with a gleam about her path, as they should plunge into some gloomier shade. There was no other attribute that so much impressed her with a sense of new and untransmitted vigor in Pearl’s nature, as this never failing vivacity of spirits: she had not the disease of sadness, which almost all children, in these latter days, inherit, with the scrofula, from the troubles of their ancestors. Perhaps this, too, was a disease, and but the reflex of the wild energy with which Hester had fought against her sorrows before Pearl’s birth. It was certainly a doubtful charm, imparting a hard, metallic lustre to the child’s character. She wanted--what some people want throughout life--a grief that should deeply touch her, and thus humanize and make her capable of sympathy. But there was time enough yet for little Pearl. “Come, my child!” said Hester, looking about her from the spot where Pearl had stood still in the sunshine--”we will sit down a little way within the wood, and rest ourselves.” CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 14 Text-dependent Constructed Response Questions Based on the Scarlet Letter Example Questions: 1. Name three specific actions that the Pearl performed. What do these actions reveal about her physical, social, and psychological maturity? 2. How does the author use contrast to develop the setting and the characters in the Scarlet Letter? Use evidence to support your answer. 3. What is the setting of the Scarlet Letter? How does the author develop the setting and then use the setting to develop the characters of Hester and Pearl? 4. Using evidence from the text, describe how the author uses nature to inform the reader. CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 15 Vocabulary Four Square Word Word Study hemmed hem ed verb, past tense German hemmen: to hem in, stop, hinder The German derivative fits the context. Word in Context Nonlinguistic Representation This hemmed it in so narrowly, and stood so black and dense on either side, and disclosed such imperfect glimpses of the sky above, that, to Hester’s mind, it imaged not amiss the moral wilderness in which she had so long been wandering. CCSS_AP(B)_p. 145 To address vocabulary, I have chosen L.11-12.4. Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases based on grades 11-12 reading and content, choosing flexibly from a range of strategies. a. Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, paragraph or text; a word’s position or function in a sentence) as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase. b. Identify and correctly use patterns of word changes that indicate different meanings or parts of speech (e.g. conceive, conception, conceivable). c. Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to find the pronunciation of a word or determine or clarify its precise meaning, its part of speech, its etymology, or its standard usage CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 16 Think Aloud The word is hemmed. I chose this word because it has multiple meanings and is Tier 2 academic vocabulary. I know the word hem that means the finished edge of a skirt or pair of pants. Hemming a road, as I currently understand the word, does not make sense in this context. If I look at the morphology of the word, the affixes and roots, I remove the “ed” which tells me it is a past tense verb. Also, I know my spelling rule that tells me to double the consonant if the vowel is short and the word is one syllable before adding “ed” so the root word is hem. I don’t recognize this as a root word so I look up the etymology of hem. The German word hemmen means to hem in, stop, hinder. This definition fits the context of the sentence. I find a picture to use as a nonlinguistic representation. I can discuss this word with my partner and share what I learned about the etymology and how it helped me understand the meaning. This page will stay in my notebook so I can review it from time to time. Every three weeks or so we play a vocabulary game using the words we put in our notebooks. I like to win, so I study a little each day. CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 17 Sample Vocabulary Practice/Assessment (Strategy from With Rigor for All, 2nd edition by Carol Jago) Word Bank Naïve- inexperienced Pensive- thinking, contemplative Wary- cautious, distrustful, circumspect Humiliating- embarrassing, shameful Question Think of the characters in the excerpt from The Scarlet Letter. Which character(s) can be described using these words naïve, pensive, wary or humiliated? Write a paragraph describing why you would describe the characters using these words and support your answer with textual evidence. Example Response Hester is humiliated because her moral dilemma has brought her shame. The narrator shares that Hester thinks the narrowly hemmed, dense, dark foot-path “imaged not amiss the moral wilderness in which she had so long been wandering.” Pearl is pensive as she contemplates how ”the sunshine does not love you. It runs away and hides itself, because it is afraid of something on your bosom.” The connections the child makes seem mature, yet incomplete because she is inexperienced and naïve. Pearl does not understand exactly what is on her mother’s bosom that drives the sun away. Hester is wary when she thinks about Pearl’s future and she tells her “Run away, child…and catch the sunshine. It will soon be gone.” Hester is distrustful of what lies ahead for he daughter. CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 18 Socratic Circle Scorecard (From Socratic Circles by Matt Copeland) 5= Hitting Target 4= Very Close 3= Narrowing Gap 2= Needs Work Student’s Reading of Engaged Supports Encourages Listens Name Text and in ideas with thinking and respectfully (Initials) Preparation Discussion references participation and builds and Stays to text in others from ideas on Task of others. 1= Not Close Questions Accepts insightfully more and uses than sound one reasoning. point of view on the text. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. First Inner Circle Second Inner Circle Time in Discussion:___________ Minutes CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 19 Socratic Circle Feedback Form (from Socratic Circles by Matt Copeland) 1) Rate the inner circle’s performance on the following criteria: Did the participants… Dig below the surface meaning? Speak loudly and clearly? Cite reasons and evidence for their statements? Use the text to find support? Listen to others respectfully? Stick with the subject? Talk to each other, not just the leader? Paraphrase accurately? Avoid inappropriate language Ask for help to clear up confusion? Support each other? Avoid hostile exchanges? Questions others in a civil manner? Seems prepared? Make sure questions were understood? Poor Average Excellent 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 20 Guidelines for Participants in a Socratic Seminar (http://www.studyguide.org/socratic_seminar_student.htm) 1. Refer to the text when needed during the discussion. A seminar is not a test of memory. You are not "learning a subject"; your goal is to understand the ideas, issues, and values reflected in the text. 2. It's OK to "pass" when asked to contribute. 3. Do not participate if you are not prepared. A seminar should not be a bull session. 4. Do not stay confused; ask for clarification. 5. Stick to the point currently under discussion; make notes about ideas you want to come back to. 6. Don't raise hands; take turns speaking. 7. Listen carefully. 8. Speak up so that all can hear you. 9. Talk to each other, not just to the leader or teacher. 10. Discuss ideas rather than each other's opinions. You are responsible for the seminar, even if you don't know it or admit it. Expectations of Participants in a Socratic Seminar (http://www.studyguide.org/socratic_seminar_student.htm) When I am evaluating your Socratic Seminar participation, I ask the following questions about participants. Did they…. Speak loudly and clearly? Cite reasons and evidence for their statements? Use the text to find support? Listen to others respectfully? Stick with the subject? Talk to each other, not just to the leader? Paraphrase accurately? Ask for help to clear up confusion? Support each other? Avoid hostile exchanges? Question others in a civil manner? Seem prepared? CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 21 What is the difference between dialogue and debate? (http://www.studyguide.org/socratic_seminar_student.htm) Dialogue is collaborative: multiple sides work toward shared understanding. Debate is oppositional: two opposing sides try to prove each other wrong. In dialogue, one listens to understand, to make meaning, and to find common ground. In debate, one listens to find flaws, to spot differences, and to counter arguments. Dialogue enlarges and possibly changes a participant's point of view. Debate defends assumptions as truth. Dialogue creates an open-minded attitude: an openness to being wrong and an openness to change. Debate creates a close-minded attitude, a determination to be right. In dialogue, one submits one's best thinking, expecting that other people's reflections will help improve it rather than threaten it. In debate, one submits one's best thinking and defends it against challenge to show that it is right. Dialogue calls for temporarily suspending one's beliefs. Debate calls for investing wholeheartedly in one's beliefs. In dialogue, one searches for strengths in all positions. In debate, one searches for weaknesses in the other position. Dialogue respects all the other participants and seeks not to alienate or offend. Debate rebuts contrary positions and may belittle or deprecate other participants. Dialogue assumes that many people have pieces of answers and that cooperation can lead to a greater understanding. Debate assumes a single right answer that somebody already has. Dialogue remains open-ended. Debate demands a conclusion. Dialogue is characterized by: Suspending judgment Examining our own work without defensiveness Exposing our reasoning and looking for limits to it Communicating our underlying assumptions Exploring viewpoints more broadly and deeply Being open to disconfirming data Approaching someone who sees a problem differently not as an adversary, but as a colleague in common pursuit of better solution CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 22 Socratic Seminar: Participant Rubric (http://www.studyguide.org/socratic_seminar_student.htm) A Level Participant Participant offers enough solid analysis, without prompting, to move the conversation forward Participant, through her comments, demonstrates a deep knowledge of the text and the question Participant has come to the seminar prepared, with notes and a marked/annotated text Participant, through her comments, shows that she is actively listening to other participants Participant offers clarification and/or follow-up that extends the conversation Participant’s remarks often refer back to specific parts of the text. B Level Participant Participant offers solid analysis without prompting Through comments, participant demonstrates a good knowledge of the text and the question Participant has come to the seminar prepared, with notes and a marked/annotated text Participant shows that he/she is actively listening to others and offers clarification and/or follow-up C Level Participant Participant offers some analysis, but needs prompting from the seminar leader Through comments, participant demonstrates a general knowledge of the text and question Participant is less prepared, with few notes and no marked/annotated text CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 23 Participant is actively listening to others, but does not offer clarification and/or follow-up to others’ comments Participant relies more upon his or her opinion, and less on the text to drive her comments Participant offers little commentary D or F Level Participant Participant comes to the seminar ill-prepared with little understanding of the text and question Participant does not listen to others, offers no commentary to further the discussion Participant distracts the group by interrupting other speakers or by offering off topic questions and comments. Participant ignores the discussion and its participants CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 24 Socratic Circles Description Text Resource: Socratic Circles: Fostering Critical and Creative Thinking in Middle and High School by Matt Copeland Web Resource: http://www.learnnc.org/lp/pages/4994 Matt Copeland, the author of Socratic Circles, explains that Socratic circles “turn partial classroom control, classroom direction, and classroom governance over to students by creating a truly equitable learning community where the weight and value of student voices and teacher voices are indistinguishable from each other.” Copeland suggests that Socratic circles help to develop “critical and creative thinking skills that will ultimately facilitate their growth and development into productive, responsible citizens.”6website According to Copeland, Socratic circles encourage students to “work cooperatively to construct meaning from what they have read and avoid focusing on a ‘correct’ interpretation of the text.”7website In his text, Copeland emphasizes that Socratic circles are not a form of classroom debate. “Debate suggests that students are competing with one another to convince an outsider of the validity of their line of thinking. A Socratic circle has students working collaboratively to construct a common vision of truth and understanding that serves all members of the group equally. There is no concept of ‘winning an argument’ in a Socratic circle; there is only the search for deeper and more thorough understanding” (26). Socratic Circles Procedure 1.On the day before a Socratic circle, the teacher hands out a short passage of text. 2.That night at home, students spend time reading, analyzing, and taking notes on the text. 3.During class the next day, students are randomly divided into two concentric circles: an inner circle and an outer circle. 4.The students in the inner circle read the passage aloud and then engage in a discussion of the text for approximately ten minutes while students in the outer circle silently observe the behavior and performance of the inner circle. 5.After this discussion of the text, the outer circle assesses the inner circles’ performance and gives ten minutes of feedback for the inner circle. 6.Students in the inner and outer circles now exchange roles and positions. 7.The new inner circle holds a ten-minute discussion and then receives ten minutes of feedback from the new outer circle. There are many variations to the time limits of each aspect of Socratic Circles, but maintain the discussion-feedback-discussion-feedback pattern is essential. Once students have mastered the structure of the Socratic circle itself, modifications can be made according to content, focus, purpose, and so on. CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 25 Socratic Circle Arguing Civilly (from With Rigor for All, 2nd edition by Carol Jago, 2011) Sentence stems to scaffold students 1. I can understand how you see it that way, but I… 2. Where did you see that in the text? 3. If I were in this character’s place… 4. Those lines make me feel as though… 5. When I compare this with what came before… 6. I can understand how you see it that way, but I… 7. Does this word have other connotations? 8. I was struck by the line where… 9. I’m unsure. Can you please come back to me? With Rigor for All, Carol Jago (2011) CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 26 Rules for Classroom Discussion (from With Rigor for All, 2nd edition by Carol Jago) 1. Students must talk to one another, not just to me or to the air. 2. Students must look at the speaker while he or she is talking. 3. Students must listen to one another. To ensure that this happens, they must either address the previous speaker or provide a reason for changing the subject. 4. Students must all be prepared to participate. If I call on someone and he or she has nothing to say, the appropriate response is, “I’m not sure what I think right now, but please come back to me later.” 5. No side conversations, copying of math homework, or texting. With Rigor for All, Carol Jago (2011) Actively Listen 1. Be other-directed; focus on the person communicating 2. Follow and understand the speaker as if you were walking in their shoes 3. Listen with your ears but also with your eyes and other senses 4. Be aware: non-verbally acknowledge points in the speech 5. Let the argument or presentation run its course Don't agree or disagree, but encourage the train of thought 6. Be involved: Actively respond to questions and directions Use your body position (e.g. lean forward) and attention to encourage the speaker and signal your interest http://www.studygs.net/listening.htm CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 27 Grammar Minilesson Based on The Scarlet Letter CCSS Appendix B Page 145 Using Syntax to Make Meaning: The road, after the two wayfarers had crossed from the Peninsula to the mainland, was no other than a foot-path. It straggled onward into the mystery of the primeval forest. This hemmed it so narrowly, and stood so black and dense on either side, and disclosed such imperfect glimpses of the sky above, that, to Hester’s mind, it imaged not amiss the moral wilderness in which she had so long been wandering. The day was chill and somber. Overhead was a gray expanse of cloud, slightly CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 28 stirred, however, by a breeze; so that a gleam of flickering sunshine might now and then be seen at its solitary play along the path. This flitting cheerfulness was always at the further extremity of some long vista through the forest. The sportive sunlight—feebly sportive, at best, in the predominant pensiveness of the day and scene—withdrew itself as they came nigh, and left the spots where it had danced the drearier, because they had hoped to find them bright. CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 29 Think aloud: I am reading along and when I get to this sentence I am lost. This hemmed it so narrowly, and stood so black and dense on either side, and disclosed such imperfect glimpses of the sky above, that, to Hester’s mind, it imaged not amiss the moral wilderness in which she had so long been wandering. The first word “this” refers back to the previous sentence. I need to know what “this” represents, the antecedent of the pronoun. The closest antecedent is primeval forest, but I need to read the previous sentence entirely to make sure this does not refer back to the subject of the previous sentence. Again I am faced with another pronoun at the beginning of the sentence “it.” Now I must read the first sentence to identify “it” to make certain that the antecedent I want is primeval. The sentence begins “The road,” which is then followed by an intervening clause set off by commas. The main clause reads “The road was no other than a foot-path.” The information between the commas tells me that the road changes to a foot-path when the travelers move from the Peninsula to the mainland. I can infer that traveling on the narrow foot-path is more difficult than traveling on the road, which would have been wider and clearer from more frequent travel. Again I can CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 30 infer that these two Wayfarers are taking the road less traveled. My question is why would a woman and her small child travel alone on a footpath into a dark forest? Where are they going? Where have they been? I go back to the main sentence “The road was no other than a footpath.” The linking verb “was” is like using an equal sign in math. (Road=footpath) Now I see that the pronoun “it” stands for the road that has now become a foot-path. I can substitute foot-path for “it” and the sentence reads “[The footpath] straggled onward into the mystery of the primeval forest. Vocabulary words straggled and primeval along with the mood word mystery are critical in this sentence. Straggle means to wander from the proper path. From straggle, I know the Wayfarers have wandered onto an improper path. They are in a mysterious place, which I think means their journey or destination might be uncertain or unknown. A primeval forest is an original forest that has never been cut. It would have been witness to original people from the beginning of time. What would this forest know about the human experience? Now I am back to my confusing sentence. This hemmed it … If I substitute antecedents for the pronouns, I might try The foot-path hemmed the primeval forest, but that doesn’t make sense; however, if I try The primeval forest hemmed the foot-path it works. Also, it makes sense that “this” should refer back to the closer noun in the previous sentence. Now I can substitute my nouns and continue reading my sentence The primeval forest hemmed the foot-path so narrowly, and stood so black and dense on either side, and disclosed such imperfect glimpses of CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 31 the sky above, that, to Hester’s mind, it imaged not amiss the moral wilderness in which she had so long been wandering. Now I am fine until I get to the words disclosed and imperfect glimpses. I know what closed is and dis means the opposite so I could substitute the word opened for disclosed. I know the word perfect, and im means not. I need to look up the word glimpses because I have no idea what it means. Dictionary.com defines glimpse as a very brief passing look, sight, or view. The troublesome part of the sentence reads and disclosed opened such imperfect (not perfect) glimpses (brief passing sight) of the sky above, that, to Hester’s mind, it imaged (to reflect the likeness of) not amiss (wrongly) the moral (the distinction between right and wrong) wilderness (a bewildering mass or collection) in which she had so long been wandering (moving from place to place without a fixed plan). After studying the vocabulary and understanding the basic meaning. I need to read the text as Hawthorne has written it and move away from my clumsy translation back to the artful way that he constructs the sentences and builds meaning. CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 32 CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 33 Strategies Proficient Readers Use Grammar Minilesson The Scarlet Letter (CCSS, App. B, p. 145) 1. Re-read for a specific purpose when meaning breaks down 2. Use punctuation 3. Find the main clause and read it without intervening phrases and clauses 4. After working the sentence re-read it fluently with comprehension 5. Visualize 6. Make connections to background knowledge 7. Look for figurative language to find layers of meaning 8. Look for parallel structure to understand how parts of a text add meaning to other parts 9. Look for patterns 10. Look for repetition CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 34 The Unit Organizer 4 NAME DATE BIGGER PICTURE CLASS 2 LAST UNIT/Experience 1 Text complexity 8 UNIT SCHEDULE Narra ve Wri ng Studying Literature 5 UNIT MAP i s ab out . .. th ro University of Kansas Center for Research on CLASS: Reading Literature ELA 5‐12 Learning 2006 b y em b ed din g Language Analyze Discuss Evaluate 6 UNIT UNIT SELF-TEST QUESTIONS h ug 3. What is the role of speaking and listening in the study of complex texts? 4. What does text‐embedded grammar and vocabulary instruc on look like? 5. What do students gain when they write about the literature they read? Wri ng about Literature b y RELATIONSHIPS c ng e l Complex e Debrief HW by s Building knowledge by grappling with r Texts Selec ng works of excep onal cra and Complex thought that offe pr of ound ins i ght s Texts g cin into the human condi on and serve Close c as models for students’ own thinking ra Reading p y and wri ng b Discussing Close the Text Reading Vocabulary Grammar Wri ng Speaking about & Listening Literature 1. How does the complexity of texts impact student learning? What student and teacher behaviors insure that close reading takes place? 2. 7 4 NEXT UNIT/Experience 3 CURRENT CURRENT UNIT UNIT 4 CLASS: Reading Literature Participant’s Manual 6 October 2011 35