Introduction to Globalization

advertisement

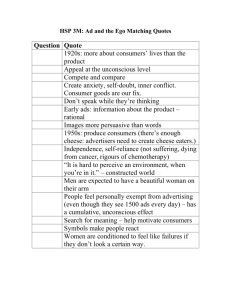

TOPICS IN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT, TRADE, AND CULTURE Scott Wentland Introduction ESC Clermont: International Week About your instructor: Visiting Professor of Economics, Longwood University Longwood PhD University is located in Farmville, Virginia, US in Economics from George Mason University GMU is located in Fairfax, Virginia…just outside of Washington DC GMU hosts an outstanding economics department, with two Nobel Prize winning economists. Originally Born from Ohio, U.S.A. and raised in Toledo, Ohio Attended Miami University of Ohio for Bachelors & Masters Day 1: Lecture Outline World poverty & institutions Why do some countries grow rich while others stay poor? Why do we trade? Specialization & Absolute Advantage Theory of Comparative Advantage Assessing World Poverty Looking at the world’s economies, we tend to ask three common questions: Why are some nations wealthy while others are poor? Why are some nations getting wealthier faster than others? Can anything be done to help poor nations become wealthy? Assessing World Poverty Three Key Facts 1. 2. 3. Everyone Used to Be Poor GDP per Capita Today Varies Enormously among Nations Growth Miracles and Growth Disasters: some countries’ economies have grown at incredible rates while others stagnate. How do we explain this? All Countries Were Poor… Most of the World is Still Poor Growth Miracles & Disasters Two Growth Miracles Japan: South Korea: annual rate of real growth1950-70 = 8.5% annual rate of real growth1950-70 = 7.2% Two Growth Disasters Argentina 1900: one of the richest countries in the world Now: per capita real GDP is 1/3 that of the U.S. Nigeria Has barely grown since 1950 Poorer now than it was in 1974 Miracles and Resources Do these “growth miracles” simply have more resources? What do economists mean by “resources”? Labor, land, & natural resources Physical capital: the stock of tools, structures, and equipment. Human capital: is the productive knowledge and skills that workers acquire through education, training and experience. Technological knowledge: knowledge about how the world works that is used to produce goods and services. Miracles and Resources A country’s amount of available resources only tells part of the story. Why do some countries have more physical and human capital and use more advanced technology? Why do some countries obtain greater output from the resources they have than others? The answers lie in the institutions and incentives that countries adopt. Institutions: A Natural Experiment A natural experiment - North and South Korea Before division after WWII Shared the same people and culture. Had similar levels of physical capital. Had access to the same technology. North Korea became a communist state with a centrally planned economy. South Korea adopted a capitalist free market model. The result 50 years later is dramatic as seen in the following photo from outer space. The Korean Peninsula at Night Institutions and Incentives Institutions are the “rules of the game” that structure economic incentives. Institutions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. of Economic Growth Property rights Honest government Political stability A dependable legal system Competitive and open markets Institutions 1. Property rights: the right to benefit from one’s effort. Provide incentives to work hard. Encourage investment in physical and human capital. If you can keep/sell what you make, then you will make more. Property rights are also important for encouraging technological innovation. Without property rights: Effort is divorced from payment → ↓incentive to work Free riders become a problem Institutions 2. Honest Government Property rights are meaningless unless government guarantees property rights. Corruption bleeds resources away from productive entrepreneurs. Corruption takes resources away from more productive government activity. Next is a list of the 10 most and the 10 least corrupt countries. Are you surprised to see who is or who isn’t on these lists? Institutions 3. Political Stability Changing governments without the rule of law results in uncertainty which leads to less investment in physical and human capital. In If you are uncertain whether the next government will allow you keep your property, then you will have less incentive to produce goods now. many nations civil war, military dictatorship, and anarchy have destroyed the institutions necessary for economic growth. Institutions 4. Dependable Legal System A good legal system facilitates contracts and protects property from others including government. Is property really yours if there is no legal system to defend it? Poorly protected property rights can result from too much government or too little government. The legal system in some governments is so poor that no one knows who owns what. Example: In India, residents who purchase land have to do so more than once because of lack of proper record keeping. Institutions 5. Competitive and Open Markets Encourage the efficient organization of resources. About half the differences in per capita income across countries is explained by a failure to use capital efficiently. Competition drives people to do more with the same resources. Example: One study found that if India used its physical and human capital as efficiently as the U.S., India would be four times richer than it is today. Institutions: Conclusions and Questions “Growth miracles” had relatively good institutions “Growth disasters” had relatively bad institutions Economic growth would become more common if more countries changed their institutions. Where do institutions come from? Culture? History? Geography? Luck? Key research question in economics: Understanding institutions, where they come from and how they can be changed? Open Markets and Trade Why are open markets important for economic growth and prosperity? Doesn’t Trade trade hurt us? causes us to lose jobs from foreign competitors. Why pay foreigners for doing something we can do ourselves? So, how that make us richer? Specialization Trade allows us to specialize Specialization allows us to focus on the work we do well. The people with whom we trade can focus on the work they do well. Collectively, the world produces more and the world is more prosperous. Above summarizes the main insights from Adam Smith’s theory of trade (sometimes called the Theory of Absolute Advantage) Trade Example: Absolute Advantage Economists like to simplify examples, while maintaining the essence of the point. Suppose we are thinking about: Two countries France Italy Two goods Wine Cheese Assumption: the goods are of equal quality and basically the exact same products across countries. Trade Example: Absolute Advantage No trade (suppose each has 36 work hours/week) 18 hours (18*1 = ) 18 wine 18 hours (18*4 = ) 72 cheese Total: 36 hours 18 wine, 72 cheese France: 18 hours (18*2 = ) 36 wine 18 hours (18*3 = )54 cheese Total: 36 hours 36 wine, 54 cheese Italy: Country Italy France Wine (bottles per hour) 1 2 Cheese (units per hour) 4 3 Goods (productivity) Trade Example: Absolute Advantage France is best at producing wine France produces more wine per hour of work than Italy. France has an absolute advantage in wine production. Italy is best at producing cheese Italy produces more cheese per hour of work than France. Italy has an absolute advantage in cheese production Country Italy France Wine (bottles per hour) 1 2 Cheese (units per hour) 4 3 Goods (productivity) Specialization and Trade Specialization (again each still has 36 work hours) 36 hours 144 cheese France: 36 hours 72 wine Italy: Trade (exchange 2 cheese for every 1 wine) Italy: 36 wine, 72 cheese France: 36 wine, 72 cheese Country Italy France Wine (bottles per hour) 1 2 Cheese (units per hour) 4 3 Goods (productivity) Comparing No Trade with Trade No Trade Trade Italy: 18 hours 18 wine 18 hours 72 cheese Total:36 hours 18 wine, Italy: 36 hours 144 cheese Exchange: 2 cheese for 1 wine Total: 36 hours 72 cheese 36 wine, 72 cheese France: 18 hours 36 wine France: 36 hours 72 wine 18 hours 54 cheese Exchange: 1 wine for 2 cheese Total:36 hours 36 wine, 54 cheese Total: 36 hours 36 wine, 72 cheese Benefits of Trade & Specialization Specialization and Trade make you richer Why? You can focus your time on what you do best Should we allow Italians to steal French cheese jobs? Yes! If it means that the French people are free to focus on what they do well. In this case, it is wine production. Result: BOTH COUNTRIES BENEFIT FROM TRADE What if we are not the best at anything? What if other countries are more productive and less costly? Trade Example: Comparative Advantage Theory of Comparative Advantage David Ricardo, British economist (1772-1823) He explained that a country being “the best” or “good” at producing something was irrelevant. Both sides can benefit from trade even if one side is better at producing everything. How do we know? We look at what economists call opportunity costs. Trade Example: Comparative Advantage No trade (suppose each has 36 work hours) 23 hours 184 wine 13 hours 54 cheese Total: 36 hours 184 wine, 54 cheese France: 18 hours 18 wine 18 hours 54 cheese Total: 36 hours 18 wine, 54 cheese U.S.: Country United States France Wine (bottles per hour) 8 1 Cheese (units per hour) 4 3 Goods (productivity) Trade Example: Comparative Advantage Now, France produces cheese relatively well France has no absolute advantage in either good. But, for every unit of cheese it produces, it only has to sacrifice 1/3 of a bottle of wine (United States has to sacrifice more wine (2) to produce cheese) France has a low opportunity cost for producing cheese (i.e. they have to sacrifice less wine production to produce cheese than United States). Trade Example: Comparative Advantage Now, United States produces wine relatively well. United States has an absolute advantage in both cheese and wine production But, for every bottle of wine it produces, it only has to sacrifice ½ unit of cheese. (France has to sacrifice more cheese, 3, to produce wine) United States has a low opportunity cost for producing wine (i.e. they have to sacrifice less cheese production to produce wine than France). Specialization and Trade Specialization (again each still has 36 work hours) States: 36 hours 288 wine France: 36 hours 108 cheese United Trade (exchange 1 wine for every 1 cheese) United States: 234 wine, 54 cheese France: 54 wine, 54 cheese Country United States France Wine (bottles per hour) 8 1 Cheese (units per hour) 4 3 Goods (productivity) Comparing No Trade with Trade No Trade Trade U.S.: 13 hours 184 wine 23 hours 54 cheese Total:36 hours 184 wine, U.S.: 36 hours 288 wine Exchange: 1 wine for 1 cheese Total: 36 hours 54 cheese 234 wine, 54 cheese France: 18 hours 18 wine France: 36 hours 108 cheese 18 hours 54 cheese Exchange: 1 cheese for 1 wine Total:36 hours 18 wine, 54 cheese Total: 36 hours 54 wine, 54 cheese Comparative Advantage Both countries are richer! It did not matter that U.S. was more productive in everything (or, that they could produce more stuff with the same resources). Important: France does do something relatively well. Does David Beckham mow his own lawn? What if Beckham was great at mowing lawns AND soccer? Beckham pays someone to mow his lawn because each hour that he’s mowing his lawn, he’s not spending that time playing soccer. His time spent as an athlete is relatively more valuable. Comparative Advantage Benefits from trade Trade allows us to use our time wisely. Our time is better spent doing jobs we do relatively well. If France produces cheese relatively well, then more cheese production means more wine (if we trade cheese for wine). Why do we care about relative costs and not absolute costs? When you produce something, it means your time is spent not doing something else. When they trade together, France allows the US to produce what they produce relatively well. And, as a result, the US pays France more for their cheese (leaving France with more wine too) Protectionist Pressures If trade is so good, why are so many against it? Losers French vineyards (in our last example) American and French autoworkers and other manufacturing employees lose jobs to foreign competition People think all of the above “could be me” What to do? Organize Tariffs: and pass laws limiting trade? a tax imposed on imported goods Quotas: a limit on the quantity of a good that may be imported in a given period of time Protectionist Pressures Tariffs/quotas makes some people richer French wine industry (in our example) Manufacturing and other trade-sensitive industries Domestic industries would have limited competition due to higher prices of imports Makes everyone else (i.e. consumers) poorer Consumers must pay higher prices for goods End up with less overall Do the losers outweigh the winners? Protectionist Pressures How do we know we’re poorer on net? Production (deadweight) losses Higher cost domestic producers are unnecessarily using resources With trade, some industries wouldn’t be wasting resources...so we would be producing more with less Consumption People (deadweight) losses pay more for goods and services But, many mutually advantageous trades are not made Consumers receive less and have fewer choices GLOBALIZATION, WEALTH, AND TRADE Scott Wentland Globalization, Wealth, & Trade What do economists mean by “globalization”? Is it here to stay? Do countries actually become wealthier from trade? What is Globalization? Competition or Cooperation? We tend to associate globalization with the increase in international trade and commerce. “Globalization is the advance of human cooperation across national boundaries.” Intentions vs. ends Do we intend to cooperate with one another? How do we achieve cooperation without intending to cooperate? I, Pencil by Leonard Read (1958) No single person makes a pencil Largely unplanned People follow prices Increasingly Global Globalization Figure 1.1 Similar story for the U.S. & France Always an Increasingly Global World? No. Late 19th and early 20th centuries were quite globalized for their time England & France traded more once they stopped warring Adam Smith & David Ricardo helped too Back to war Between WWI & WWII trade declined rapidly Hawley-Smoot (1930) tariff in the US increased tariff to very high rates The rest of the world responded by passing their own tariffs Can Globalization Take a Step Back? Understanding globalization and international economics is key. Political rhetoric (particularly economic fallacies) has the potential to reverse globalization How do we reverse globalization? Encourage policies of self-sufficiency Make foreign products more expensive and reduce trade. Do We Really Want Globalization? Yes. But why? Globalization & trade makes us: 1. 2. 3. Wealthier More reliant on others (Yes, this is actually a good thing…) More diversified Wealth & Trade Very tight link between the wealth & (freer) trade Openness Wealth (Boudreaux’s Figure 2.1) Trade Openness Index: Most open = highest real incomes, highest growth Least open = lowest real incomes, lowest growth (The graphs in the proceeding slides are from the book Globalization by Donald Boudreaux. Wealth & Trade Openness Growth, whether you’re rich or poor (Boudreaux’s Figure 2.2) Developed Open & Developing Countries developing countries grow faster (than closed) Open developed countries grow faster (than closed) Wealth & Trade (continued) Openness Wealth, within countries over time (Boudreaux 2.4) China (1978 – ends isolation) India (1991) S. Korea (1964) Economic Freedom Wealth & Trade (continued) Money isn’t everything, but wealthier people… Live longer, have lower infant mortality rates and: Access to clean water, modern healthcare, AC & heat Less arduous jobs Have a better quality of life Achieve Have higher levels of education, etc. less/no child labor Work fewer hours Wealth & Trade (continued) Disasters Haiti (2010) – 7.0 Magnitude, 200,000 200,000+ Of a population of about 10 million San Francisco (1989) – 7.0 Magnitude 67 people dead people dead Of a population of over 7.4 million people Why such a difference? Haiti: GDP per capita $793 San Francisco Bay: GDP per capita $33,000+ Wealth & The Environment Industrialization Pollution, right? Yes & No. Environmental Kuznets Curve (Figure 2.12) Pollution rises until about $8,000 per capita Some estimates put it at $5,000 per capita Pollution falls thereafter Wealthier countries can afford to care about the environment Have higher environmental performance scores Have higher levels of environmental sustainability Environmental Kuznets Curve Wealth & Inequality All boats rise in a rising tide…the poor benefit as everyone else does Dollar & Kraay (2001), study published in the American Economic Review Concluded: poor countries actually have more income inequality than rich countries Reliance & Trade Hong Kong covers 422 sq. mi. and has 16,580 people per sq. mi. 5% or 21 sq. mi. is arable land per capita annual income of $32,900…compares to: Belgium $31,400, Switzerland $ 32,300, and France of $29,000, Sweden $29,800, Germany $30,400. Singapore, Japan, Paris or any major city Reliant is another word for specialized Diversification & Trade Suppose Haiti was an isolationist country If Suppose your bank only lent locally If all your eggs are in one basket… all your eggs are in one basket… Good results? Investing, Buying/selling goods globally reduces risk Reducing risk is what diversification is all about A DYNAMIC ECONOMY: TECHNOLOGY, OUTSOURCING AND JOBS New technology What if we invented a new X-ray analysis machine It can analyze more basic X-rays, for cheap New Technology & Jobs Radiologists lose (part of their) jobs Price of (some) X-rays fall, consumers are better off Radiologists are free to do more productive things Like analyze more complicated X-rays Some radiologists may need to get more schooling New Technology & Jobs Suppose your grandfather has been in a coma for 30 years. He walks into a modern electronics store to buy a television: He will likely be shocked by the advancement of televisions size, clarity, efficiency, etc. New technology is probably the most noticeable sign of progress Historically, some have resisted technology in fear of change, but modern generations have embraced it Outsourcing What has changed? Outsourcing Whether technology or foreigners replace our labor, we have progress Menial tasks or non-menial tasks The ends are the same whether a foreigner completes the task or a machine does Technology and trade can save labor AND make us better off We (and the next generations) are free to do other, better things Just as the type-writer repairman is free to pursue a career in Information Technology Some Conclusions Trade is mutually beneficial (both individually and internationally) David Ricardo’s Theory of Comparative Advantage Specialize in low opportunity cost items Outsourcing and trade is like technology Easy to see how it makes us better off with this analogy Like technology, it lowers our own costs Like technology, it frees up our time to do other, more productive jobs What is Ahead: Why do people in poor countries accept these jobs? Many jobs Western Europe and the U.S. outsource are low-paying jobs that a menial or tedious Next: we will look at why poorer countries takes these jobs and the nature of the labor market. POVERTY, DEVELOPMENT, AND GLOBAL INSTITUTIONS Scott Wentland Globalization & Poverty Is globalization rigged? Are greedy corporations simply exploiting the poor for profit? Shouldn’t the poor countries have better working conditions and labor standards? Are globalization organizations pawns in this capitalist conspiracy? Do globalization organizations really alleviate poverty? Exchange Thank You – Thank You Both sides benefit from each transaction Both driven by self-interest For example, buying a carton of milk Money is a medium, not an end. Globalization & Labor Labor is a mutually advantageous exchange Laborer values the wage more than the time & effort Employer values the time & effort more than the wage Exploitation implies that someone is getting a bad deal Someone is usually getting a bad deal if they are coerced into taking that deal If the poor are coerced, then your disagreement is not with capitalism or free trade…it’s with the government & institutions the permit coercion Economists look at choices & tradeoffs May not approve of X, but defend the choice Globalization & Labor Market forces set the wage Workers and employers (via competition) set wages Remember, employers willing to pay: Wage = Marginal Product * Price Wage (W) is the cost of employment What if W > MP * P? What if W < MP * P? Producers lose money, and must fire some workers or exit industry Producers make profit, and must hire some workers or more producers will enter the industry They bid up wages, bid down price The most productive are hired first, the next workers are less productive (bringing MP down) We can also think of Wage = money wage + benefits Labor Example #1 – How Markets Work W = MP * P Suppose a worker can make 10 cloth per hour, MP=10 Suppose the world price of cloth is $1, or P = $1 W = $10 in a competitive market Why? If W < $10…say $5, more producers see profit to be made in this industry Existing factories expand, hire more workers More entrepreneurs enter industry, bid up wages If W > $10, say $12, producers take losses and end up leaving the industry exit or fire workers bids down wages until W = $10 The Emergence of Labor Standards What I mean by labor standards or working conditions: Any non-wage benefit to a worker that is also a (nonproductivity-enhancing) cost to the employer Examples: working conditions (air conditioning, comfortable chairs, etc.), healthcare, safety equipment, other fringe benefits The Emergence of Labor Standards Where labor standards come from: Some are imposed by “experts” in government Many labor standards come from lawsuits With lawsuits: employers take measures as a result of or to avoid liability. A very useful reform might be aimed at reforming legal systems in countries that have a poorly functioning one. Most other standards arise out of mutually agreeable negotiations Should we improve poor countries’ labor standards through trade policy? Globalization & Labor Standards Money wage + benefits = Marginal Product * Price What if rich countries believe that all countries should have our labor standards? Money wage + benefits = Marginal Product * Price Money wage decreases, benefits increase If the workers wanted this, why didn’t they negotiate this before the U.S. imposed this? Rich countries might believe that poor people should eat steak too… Labor standards are like other normal goods Poor people usually prefer a higher wage, so they may decide not to negotiate for better labor standards Labor Example #2 – Labor Benefits W + benefits = MP * P MP & P same as last example…MP = 10, P = $1 If benefits cost the employer, say $2, then the wage will have to be reduced by the same amount $8 (wage) + $2 (benefits) = 10 units * $1 per unit The worker “buys” the labor standards This may not be a tradeoff the worker was willing to make…the worker may be worse off The worker, if in poverty, may just rather have the $2 Just as the worker may not choose to buy steak dinners By imposing benefits, you are removing choices Labor Example #3 (monopsony) What if W + benefits < MP * P ? Some poor workers do not have many choices because they have few options If a sweatshop is the only employer around, that may be the worker’s best alternative Say W = $5, benefits = 0 Rich countries could demand that workers get higher benefits and labor standards Now, benefits = $2, what will likely happen to W? Should go down $2, because the monopsonist will still want to pay a total compensation of $5 Or, perhaps some other unintended consequences… Globalization & Labor In either competition or monopsony, when standards or benefits go up, employers compensate less If for some reason total compensation is raised (by, say, a minimum wage law), then Labor looks relatively less attractive (it is now more expensive) These employers may substitute labor for more capital Some poor people will lose their jobs again, lose choices The low wage workers may lose part of their comparative advantage Makes US workers and other rich countries relatively more attractive Good for US workers, and some poor people will lose their jobs Globalization Results What if the free market produces bad results? We then must ask: Why do they choose to work there? Remember, labor is an exchange Even monopsonists have competition… What are their alternatives? Farm labor (which is no picnic) Scavenging (garbage dumps, forests) Crime Prostitution Sometimes “saving” workers from bad jobs means that they have to turn to worse alternatives Raising wages/benefits fewer jobs Globalization Results If there is monopsony or collusion, what is the answer? Monopsony & collusion aren’t really free markets Encourage competition so wages can be bid to equilibrium levels and ensure that workers get what they are worth What if workers aren’t worth that much? Education & raising productivity Workers earning wages now may help put kids through school Institutions Good institutions will facilitate this process For example: rule of law & well-defined property rights Well-functioning, stable (non-invasive) government How Can We Help the World’s Poor? Top-down approach Try to figure out what countries should do, and tell them to do it Or, give them a monetary incentive to do it World Bank IMF Bottom-Up approach Let individual countries and individuals figure out what they should do Promote individual choice World Bank Founded at Bretton Woods in 1945 Bretton Goal: get the world economy going again after WWII Also, establish a global fixed exchange rate regime International Bank for Reconstruction and Development Fund Woods agreement creditworthy governments rebuild infrastructure International Development Association (est. 1960) Fund poor countries, with various strings attached World Bank The World Bank is more known for the IDA Provides low interest and interest free loans to poor countries Provides outright grants to poor countries Has provided $2.3 trillion (along with other organizations and countries) to poor countries Money is supposed to go to infrastructure In return, they’d like to be paid back So they have strings attached… World Bank Why is this controversial? Strings attached (some people don’t like these): Freer trade policies Looser regulations and less red tape Sound monetary and fiscal policy Corruption Corrupt (everyone doesn’t like this) governments may squander loans “New” governments refuse to pay back old loans Officials give infrastructure projects to their buddies Top-down Recipients are skeptical of Washington They don’t always know what’s best: e.g. empty schools World Bank Has it worked? Here are some results from studies by economists: Peter Bauer: aid reduces growth b/c it props up corrupt governments Burnside & Dollar in 2000 A.E.R.: aid good for sound governments, bad for unsound governments Easterly, Levine, Roodman said aid has no impact, others agree or say negative International Monetary Fund Conceived at Bretton Woods, the IMF was set up to facilitate global fixed exchange rates If a government was short on funds that it would need to fix its exchange rate, the IMF could loan them money We will return to fixed exchange rates in a couple weeks This was supposed to bring exchange rate stability like the gold standard did 1971 the global fixed exchange rate regime ends What is the IMF to do? International Monetary Fund Describes its goals as: Monitoring Gives economic & financial developments policy advice Financial crisis prevention & aid Loans and policy advice Like the World Bank, policy advice is intended to help the country pay back the loan International Monetary Fund Why is it controversial? Many of the same reasons as the World Bank Top-down Sometimes It micromanagement is unpopular, often ineffective confused with the cause of financial crises is politically easy to blame creditors What Should We Do? Would free market economists (like David Ricardo) prescribe? 1. Rich nations should open their borders (to trade…and immigration helps too) 2. Stop trying to create good economies in nations with bad governments (World Bank & IMF…we’re looking at you!) 3. Reward reforms after they take place 4. Encourage microlending Microlending “extending very small loans to those in poverty designed to spur entrepreneurship” Microlending allows individuals in poor countries to become entrepreneurs Helps an economy build from the bottom up How is this different from simply “foreign aid” or aid from international organizations like the World Bank and IMF? Microlending is lending directly to individual entrepreneurs, while the organizations tend to lend to governments in an effort to let wealth trickle down to the general population. Microlending You can take an active role yourself! Visit: www.kiva.org www.lendforpeace.org www.microloanfoundation.org.uk You can view microlending as charity (with good incentives) OR a profitable opportunity Either way, both the lender and borrower win. Institutions as a Recipe Economists understand the ingredients in good institutions that foster development, but they have a difficult time figuring out the correct recipe. You may know what is in a croissant, but baking a perfect croissant requires a lot more knowledge. You can think of the interaction between the economy and institutions as an incredibly complex recipe Economists and governments are far from perfecting economic development and institutions. Do we have hope? Absolutely. People interacting within markets tend to improve their circumstances over time. FREE TRADE VS. FAIR TRADE Free Trade vs. Fair Trade What if free trade is unfair to workers and small farms? Can we be socially responsible and help them out by purchasing “fair trade” products? Up for discussion: Problem of free trade vs. Solution of fair trade An example using the coffee bean industry All-pay auction & rent-seeking Economics of fair trade licensing Unfair trade? Problem: farmers and other low wage workers are in poverty in developing countries Coffee bean industry These farmers allegedly have: Poor working conditions Child labor (under 18) Poor environmental conditions (including “unsustainability”) Very low pay/profit Fair Trade Products...are they fair? Solution: establish voluntary requirements and a certification that will allow these producers to receive a premium for their product Consumers pay a higher price for coffee in exchange for knowing that those who receive it: Are paid more Have better working conditions Have higher environmental standards This sounds fantastic. It is completely voluntary. These consumers are better off. Fair trade producers feel better off too. Economics of (Coffee) Production Suppose the world price of coffee = $1/lb Under “free trade,” coffee producers will produce coffee so long as: marginal cost ≤ $1/lb If (average) cost ≥ $1/lb, they’re losing money Stop growing it, or plant/do something else Suppose average cost is 95 cents per pound Profit = 5 cents per pound Economics of (Coffee) Production Suppose the fair trade price = $3/lb Under “fair trade,” coffee producers will produce until: marginal cost ≤ $3/lb These higher standards have compliance costs Environmental and labor standards have costs With these costs, suppose average costs = $2/lb, about $1.05 more than the free trade farmers $1 profit per pound now Free Trade vs. Fair Trade Free Trade: razor thin $0.05 per pound profit Fair Trade: much larger $1.00 per pound Look how great fair trade is These farmers have: More money Safer production Cleaner, more green production All-Pay Auction Bid for 5 euro Rules: 1. The highest bidder wins 2. You pay your bid regardless, whether you win or lose. Rent-seeking “the socially costly pursuit of wealth transfers” A simple example: theft You had the $5 The thief gets the $5 Any time, effort, resources spent by the thief = deadweight loss to society The thief could be using his time doing something productive. Instead of $5, the society could have a $10 if the thief spent his hour, say, making something worth $5. How is this relevant to fair trade products? Fair Trade & Rent-Seeking Rent-seeking…spoiler of idealism Fair trade products offer a premium, which is a transfer from consumers to producers A win-win for some But, plays out much like our all-pay auction Fair Trade and Rent-seeking Fair trade certification cannot go to everyone (just as everyone can’t win the auction) Not everyone is willing to pay the premium Quantity Growers prefer more profit to less Quantity Demanded: fair trade < normal trade Supplied: more people want to sell at $3 Fair trade certifiers can only certify part of the market and buy the amount demanded at the $3 price, even if everyone technically complies What Actually Happens? Suppose the world only demands a third of their coffee to be fairtrade It’s actually a much smaller fraction One out of three farmers can get the $3 price The other two have to sell at the world price ($1, possibly even less) What Actually Happens? Rationally, each might select fair trade: avg cost $2 One of them gets $3/lb, profit = $1per pound The other two sell at $1, lossing $1 each Overall, the coffee farmers are poorer! Fair Trade…sigh. Summary: The premium offered to the potential farmer is a rent (in the way economists define a “rent”) Producers spend resources in order to get this premium Similar incentives exist when the government hands out quota trade licences Producers end up wasting real resources , and they can either be poorer overall or at least no better off, collectively. Silver lining? But, if they comply with fair trade standards, that’s good right? The losers take real losses. They’re What’s better off doing nothing (or something else) more environmentally friendly than fair trade? Growing nothing is more environmentally friendly! Toyota Prius vs. walking Why Buy Fair Trade Products? Everything about it sounds good... ...except the rent-seeking part We see who we help. Gordon Tullock’s experience in China, an example. Quotas & tariffs Fair trade farmers So, what now? Development is tricky...there is no silver bullet or cure-all solution. You would think paying poor people more would be straightforward and would make them better off. But, incentives and unintended consequences interrupt our plans. Next: economic development GLOBALIZATION AND CULTURE Is Globalization Unfair to Culture? We may be wealthier from trade, but money/wealth isn’t everything... What if we lose some of our culture to global forces? Will the world be some unified Western/Americanized culture? If so, should we (or the world) try to stop this? Cultural Aspects of Globalization With wealth comes more culture Much of what we call culture is a luxury Ancient Greeks were relatively wealthy & cultured Culture is not just for the wealthy anymore If the poor & middle class have money, they can fund culture (music & arts) Technology’s role in expanding culture Cultural Aspects of Globalization Isn’t global culture just more commercialized? What 1. 2. does that mean? Commercial culture is more responsive to consumers Commercial culture is more dynamic, always changing Cultural Aspects of Globalization Globalized culture = homogeneous culture? Paris, Texas feels more culturally similar to Paris, France Diversity used to be across georgraphic space moreso Now: we have more local diversity Cultural Aspects of Globalization How does this affect travel? With more local diversity, you don’t have to travel to Texas to eat barbeque or Tex-Mex food But, if you have local French-Texas food, you may be inspired to try it in Texas If you eat French-Italian food, you may desire to travel to Italy to eat more authentic Italian food Cultural Aspects of Globalization We may lose some of our culture to competition from other cultures What In do we get? a market-oriented economy, we only get what we want... We If we don’t want, say, Texas barbeque, then the restaurant goes out of business. If you want Thai food, then the restaurant thrives and stays. get more diversity locally, allowing us to get a flavor of more culture than ever before. Both of the above can be seen as a strength of globalized culture. Summary Trade and globalization deliver: Wealth and prosperity More culture locally How do we help the world’s poor? Trade and improving their institutions (as best we can) International organizations (like the World Bank and IMF) have very limited success in this area “Fair” trade products only have very limited success, given its rent-seeking incentive structure. Summary (continued) Do we have hope for the future? Yes! The most success has been through markets China, South Korea, India, Singapore, etc. Outsourcing (sometimes called off-shoring) also helps rich countries and poor countries streamline their labor forces and create a more efficient, more prosperous world. Expanding individual choice allows the global economy to be more dynamic and efficient, as wealth continues to reach to more places around the world.