Low - DISASTER info DESASTRES

advertisement

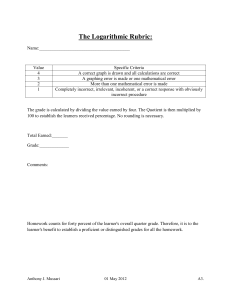

Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Improving the policy process PAHO Leaders 2006 Disaster risk reduction, mitigation, preparedness and response •Pan American Health Organization •Regional Center for Disaster Risk Reduction, UWI •CDERA Thursday 23rd November 2006 Sunset Jamaica Grande Resort, Ocho Rios 21/03/2016 Professor Anthony Clayton University of the West Indies Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Problems, problems… Problem: why do so many government policies fail? Common reasons: failure to understand the task, unhelpful misperceptions, assumptions and politics, policy conflicts, resulting in incoherent priorities & unachievable missions. Examples: χ χ χ χ χ Why do countries get poorer when aid flows increase? Why do we negotiate for aid programs that damage our economy? Why do measures to protect jobs increase unemployment? Why do government agencies undermine each other? Why can’t we solve the drug problem? Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Example: War The nature of war has changed Wars were formerly between nations; the majority of conflicts today involve civil wars/insurgencies. War today is more likely to involve infiltration rather than invasion. Wars are increasingly asymmetrical, between security forces and unconventional irregular forces. In traditional warfare, most of the fatalities were soldiers. Today, most of the casualties are civilians. The nature of war has changed fundamentally; more significant changes are expected over the next 10-20 years. The way in which the issues are perceived by the general public (taxpayers, voters, recruits) has not kept pace. So there is an increasing disconnect. Even more important, the way in which the issues are perceived by the professionals has not kept pace… Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Julian Borger, The Guardian Tuesday September 25, 2001 Wargame exposed gaping hole in Pentagon strategy • • When terror came out of a clear blue sky on September 11, some of the Pentagon's top brass were given a jolting reminder of a wargame they played in 1997. In the game, the US was pitted against a zealous, decentralised terror organisation very like al-Qaida, and the US lost. Each time the US forces thought they had scored a blow against the terror organisation, it would regenerate itself to strike on another front. It emerged from the campaign more or less unscathed. That was four years ago, but some of the military strategists who organized the game believe the Pentagon failed to learn the lessons from the wargame, and said yesterday that the US military was still a long way from readiness to fight the adversary it now faced. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • • The Pentagon: still fighting the wrong war According to Doug Johnson, a strategic studies professor involved in the 1997 exercise, the army lost because “it didn't want to play that game”. The army brass, Dr Johnson said, “were intent on fighting a variation of a war against large tank armies on the central plains of somewhere”. At one point, the Pentagon officers involved became so frustrated with their elusive opponents that they asked for the game organizers to have a friendly government's armoured battalion defect to the other side. “They did it to give someone to blast,” Dr Johnson said. “Everyone went away feeling viscerally satisfied.” As a result, they missed the point. The terror organisation still had most of its cells in place, and a functioning financial network. “Within the contours of that particular game, the American forces and their allies simply weren't configured to deal with an enemy like the one we created,” said Steven Metz, head of the Army War College's regional strategy and planning department. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Lessons? This illustrates three points in policy analysis: • Distinguish between perception and reality. • Be wary of the ‘Conventional Wisdom of the Dominant Group’ (COWDUNG), as a failure on a core assumption is likely to be fatal. • The importance of seeing both the current position and the underlying context or trend. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Making better policy Question: how can we increase the chances of success? Answer: a more systematic approach, to help us • Control for preconceived ideas and assumptions • Check the facts, get the problem into focus • Identify our options • For each option, identify costs and trade-offs • Agree our priorities • Build the necessary consensus about the way forward • Implement! • Monitor, change tactics if required, stay focused on the goal Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Bardach’s ‘Eightfold Path’ lists the main steps Define the problem. What are we trying to achieve? Assemble the evidence. What are the facts? Construct policy alternatives. What can we do? Select the criteria. How are we going to decide which is the best policy? Project the outcomes of each policy option. What would happen if we tried this? Assess the trade-offs. How much will this cost? What are the chances of success? Could this tactic create some other problem? Decide. What are you going to recommend to the Minister? Present. Set out the problem, your analysis and your recommendation. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies 3) Constructing policy alternatives • • • • • • Must be evidence-based (from stage 2). Take into account a range of expert advice and stakeholder views. Represent the main bodies of opinion. Help to bring issues into focus (usually achieved by making sure that alternatives are sufficiently diverse). Example 1: Swedish defence policy Example 2: Go Big, Go Long, Go Home. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies 4) Select the criteria What is important? Is it: • Results at any cost • Results, provided that the process is not too expensive • Results, provided that they can be achieved without upsetting anyone with a lot of political influence • Not to change anything, but to make it look as though we are taking the problem seriously So does the proposed solution have to be: • The solution that we think has the best chance of success? • The cheapest/quickest/most legal solution available? • The most politically-acceptable way forward? • The one that will make us look good? Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies 5) Project outcomes for each option This is most technically difficult step, because: • We have to be realistic, rather than optimistic or pessimistic • We have to resolve very significant uncertainty into a clear decision, on which much will depend. • It is about the future, NOT the present Key questions: what would happen if we did this? • Have we tried anything like this before? What happened that time? Why? • Has anyone else tried anything like this? What happened to them? Were the conditions similar? • How will people react if we do this? How will the community respond? Will there be political problems? How will the different interest groups react? Could there be legal challenges? Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Estimating impacts and costs Example: the cost of crime control in Jamaica: • ‘For J$180m we can reduce homicides by 5%’. • If 5% = 80 homicides, cost of reduction = $2.25m/homicide. • What are the chances of success? 90%? 50%? 10%? 1%? • What are the risks of unwanted side effects? • How does this compare against e.g. investment in schools? Bearing in mind that: o Job security increases unemployment o Safer drivers take more risks o Free zones encourage relocation, not job-creation Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies 6) Dealing with trade-offs • • One option is clearly the best (rare) Each option has a different combination of costs and benefits (the usual situation) Option Cost Chance of success Risks A Medium High High B Low Low Medium C High Medium Low Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • Aggregated vs disaggregated decision-making Aggregated: resolve everything into a single numeraire (usually cash). Disaggregated: use matrices, maps and diagrams to keep more dimensions in view. There are pros and cons for each approach. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Aggregated Low: 0-3 Medium: 4-6 High: 7-10 Option: make negative factors (e.g. cost, risk) negative numbers. Option Factor A cost Factor B – prospects Weighting *2 Factor C risks Total Plan A (Medium) -5 (High) 8 16 (High) -8 3 Plan B (Low) -2 (Low) 3 6 (Medium) -4 0 Plan C (High) -7 (Medium) 6 12 (Low) -3 2 This one! Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Probability/impact matrix • • • The conclusions from a policy exercise usually have to be absorbed into a government (or business) agenda that is already crowded. It is important to have greater clarity about future problems and potential solutions, but that does not remove the need to make the large number of day-to-day decisions involved in managing a Ministry or government agency. So it is important to have priorities for action. A probability – impact matrix is a way of organizing these priorities. It is similar to the triage used by military doctors when dealing with incoming casualties. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Probability/impact matrix Low impact Low probability Ignore High impact Monitor carefully Risk of critical failure! High probability Low priority Top priority Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • • High impact, low probability (we thought…) It is sensible to allocate most time and resources to high impact, high probability events, but it is also important to monitor high impact, low probability events… The US Federal Emergency Management Agency knew that New Orleans was potentially vulnerable to a hurricane, and had identified this as one of the three worst disasters that could befall the United States. This was, however, seen by the administration as a low probability event. On the 28th–29th August 2005, Hurricane Katrina resulted in a 28-foot storm surge as well as torrential rain, the latter raised the height of Lake Pontchartrain by 7.6 feet, and the combination overwhelmed the levees that protected the city of New Orleans. About 80% of the city, which is on average about 6 feet below sea level, was then flooded. Unprepared. The Washington Post. Monday, September 5th, 2005 Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies 7) Decide • • • Are you convinced? Are your colleagues convinced? Are the external experts, independent advisors, stakeholders convinced? Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies 8) Final presentation State the following: • The problem • The analysis of trends, causes • Options, intervention points • Benefits, costs, trade-offs and risks • Recommendation Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Project management tools There are a range of useful tools, including: • Project cycle management • LogFrame planning • Critical Path Analysis • PERT analysis • Gantt charts These can help to: • Identify the important sub-tasks. • Identify the dependencies between sub-tasks. • Organize the dependent sub-tasks into the appropriate sequence. • Identify potential vulnerabilities. • Identify the minimum time required to complete a project. • Identify where resources can be optimally allocated. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Project cycle management (1) Most projects can be divided into a 6 phase project cycle: 1. Defining the theme. This is the choice of area, usually a list of key problems that require a policy intervention (typically scoring high on risk, public concern, or assessed chances of success). 2. Project identification. This is the initial formulation of ideas for the actual project, including objectives, expected results and a list of the actions to be taken. The goal at this stage is to work out whether it is worth going ahead with a feasibility/pilot study. If the answer is yes, then the next step is usually to draw up the terms of reference and undertake the study. 3. Formulation. This involves looking at the results of the feasibility or pilot study and specifying the project itself. Objectives, expected results and a list of the actions to be taken must now be set down in precise detail. These must then be checked back against the theme defined earlier. If the project is going to require external funding, it is at this stage that you decide whether or not to draw up a bid for funds. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Project cycle management (2) 4. 5. 6. Financing. For those projects that require external funding; this stage involves drafting the funding proposal, bidding for and securing funds, negotiating and signing the contracts. Implementation. This involves executing the project, monitoring progress and achieving the results. Evaluation. This stage involves analyzing the results and assessing the impact of the project both during and after its implementation. The goal is to identify any lessons to be learnt that could help with other projects, both now and in the future. Projects that require external funding are often phased, with the release of funding for each stage conditional on the completion of a full evaluation of the previous stage. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies LogFrame: risk reduction What is LogFrame? • Logical Framework (LogFrame) planning involves analyzing and setting out, in a systematic and logical way, the objectives of a project and any causal relationships between the objectives of a project. • It involves working towards these objectives, monitoring progress and checking that the objectives have been achieved. It also involves establishing the extent to which the success of the project depends on factors that cannot be controlled, and the extent to which the project is therefore exposed to risk. How LogFrame help? • By helping us to think methodically and identify all the factors essential to the success of the project. • By encouraging us to check and test our ideas, monitor progress, identify problems and take remedial action while there is still time to save the project. The activities can start if the preconditions are met; the activities will lead to results if the the results will accomplish the project purpose if the assumptions are met; achieving the project’s purpose will help to achieve the overall objectives if the assumptions are met. Professor Anthony Clayton, assumptions met; University of the Westare Indies Intervention logic Verifiable indicators Sources of verification Means Costs Assumptions Overall objectives (the contribution) Project purpose (the point) Results (the achievement) Activities (the actions) LogFrame matrix Preconditions Start Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Critical Path Analysis (1) Critical Path Analysis and the related PERT model were developed in the 1950s to manage military projects, but are now more generally used to manage any particularly large, complex project. Another related tool, the Gantt chart, was developed three decades earlier. These tools involve listing all the subtasks in a project, then organizing them into two groups: 1. Sequential: the first group consists of those tasks that have to be completed in sequence, because each stage depends on the one before. When building a factory, for example, the foundation must be finished before the load-bearing walls go up, and the walls must be ready before the roof can be fitted. 2. Parallel: the second group consists of those tasks that do not depend on the completion of other tasks. These can therefore be completed in parallel, i.e. at the same time as other tasks. In the same factory building project, for example, the contractor might decide that the tarmac for the car park can be laid at any time; this does not depend on progress with the foundations, walls or floors of the main building. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Critical Path Analysis (2) • • The tasks are then represented in a diagram which shows the flow of events. The critical path is the line through the series of sequential events. This shows the minimum amount of time needed to complete the project as a whole. This also shows where the project might be vulnerable, because any failure on the critical path will always have implications for either the timetable (the completion will be delayed) or the budget (we will have to hire more people to get this phase finished on schedule). The key points along the critical path usually serve as the decision points for the project. This process shows where additional resources would have the most effect. Additional expenditure on a critical path event can shorten the amount of time required, and help to get a late project back on schedule. Hiring more bricklayers, for example, can help to get the walls finished earlier, thus making it possible to get the roof fitted. Additional expenditure on a parallel task, however, such as bringing in another roller to level the car park, will not help to shorten the timetable. This reveals how resources can be reallocated from parallel tasks to sequential tasks in order to speed up a project. This sort of tactic is sometimes referred to as a crash action programme. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Program Evaluation & Review Technique (PERT) PERT is a form of Critical Path Analysis which also corrects for the fact that most people underestimate how long each task will take, while some people will overestimate the time required in order to inflate their bonuses. PERT is calculated by estimating the shortest possible time each task will take, the longest likely time each task could take, and the most likely amount of time that each task will actually take. In effect, PERT uses a band of values, with a top and bottom end and a ‘most likely’ value, as opposed to a single value. This band is then resolved into a single value, usually in the following formula: shortest time + 4* the most likely time + the longest time/6. So if, for example, the shortest time was 2 days, the longest time 8 days, and the most likely time 4 days, that would give: 2 + (4*4) + 8 = 26/6 = 4.3 days. This final value is then used instead of the shortest time value of 2 days or the longest value of 8 days, thus correcting for overoptimism or under-bidding. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Visual tools Critical path, PERT and Gantt charts (Gantt charts were developed by Henry Gantt in 1917) are usually shown as horizontal bar charts that show the important tasks over time. These are useful visual tools for keeping track of projects. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. How to make Critical Path, PERT or Gantt charts Make a list of all tasks/activities involved in the project. Put them into sequential order. Estimate the time it will take to complete each task and put the time next to that task on the list. Readjust the sequence of tasks as necessary. Determine who is responsible for each task on the list and put their name next to that task. Label the chart across the top by day/week/month. Label the chart along the left side with all the tasks. Draw horizontal bars for each task beginning at the start date for that task and ending with the completion date for that task. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Activity i/c Prepare proposal Fred Secure budget John Recruit new staff Mary Train new staff Joan Assess existing staff Dave Maintain equipment Fred Maintain premises Bill Jan Critical path (sequential) Example Feb Mar Apr Non-Critical (non-sequential) May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies 5) Project outcomes for each option This is most technically difficult step, because: • We have to be realistic, rather than optimistic or pessimistic • We have to resolve very significant uncertainty into a clear decision, on which much will depend. • It is about the future, NOT the present So how do we plan for the future? Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies The problem with forecasts… “Sophisticated, highly-paid economists have successfully predicted seven of the last three global recessions” (various sources). “Never make forecasts; especially about the future” - Sam Goldwyn Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Why do forecasts fail? 1) Trends change. We start from the current position, identify and extrapolate trends. We tend to assume that these will continue – but eventually they don’t. Competition intensifies, markets saturate and preferences change. 2) Parameters change. Market trends are shaped by underlying social and economic factors e.g. demographics, productivity growth and technological development. These structural factors usually change slowly– but external shocks or new ‘disruptive’ technologies can represent discontinuities (or tipping points) that precipitate more rapid change and restructure markets. Trend change is (in principle) predictable….but it is difficult to anticipate discontinuities. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Can we do better? Conventional forecasting results become less reliable at times of significant, rapid and pervasive change We are living in an unprecedented era of accelerating technological, economic and social change, driven by: o New technologies, such as informatics, biotechnology, and nanotechnology o Global trade liberalisation, which could increase contestable world output from 20% of the total to 80% of the total by 2030 o The re-drawing of world geopolitical parameters o Changing pattern of resource demand, environmental impacts Are there more reliable decision/planning tools for times of change? Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies What is foresighting? Foresighting is a tool used: to inform decision-making to help people anticipate future opportunities and avoid problems Foresighting involves: envisioning a range of possible future scenarios, testing these rigorously, then back-casting to present day, and mapping out the steps needed to achieve the preferred scenario/avoid the worstcase scenario. The foresight process itself is important, because: it clarifies and challenges assumptions it encourages shared visions and flexible thinking it creates new ‘knowledge networks’ Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Changing parameters: climate change Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Earth's temperature is dangerously high - NASA • Researchers at Nasa's Goddard Institute for Space Studies said that Earth's temperature was now reaching its highest level in a million years. Dr James Hansen, who led the study, said further global warming of just 1°C could lead to big changes to the planet. “If warming is kept less than that, effects of global warming may be relatively manageable,” he said. “But if further global warming reaches 2° or 3°C, the Earth may become a different planet [to] the one we know now. The last time it was that warm was in the middle Pliocene, about 3m years ago, when sea level was about 25 meters (80 feet) higher than today.” • The study showed that there was already a threat of more extreme weather like the strong El Niños in 1983 and 1998, when many countries around the world had devastating floods and tornadoes. • Adapted from Hilary Osborne Tuesday September 26 2006 The Guardian Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Hurricane Katrina, 2005, S E of New Orleans Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Flooding in Bangladesh The dispossessed. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Is this a solvable problem? Previous environmental treaties have had partial success: The Montreal Protocol, which limits CFC emissions. The Basle Convention, which shipments of hazardous waste. controls trans-boundary But these are relatively solvable problems compared to energy use; carbon emissions derive from the use of our primary energy sources. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • • Kyoto – redundant before ratified The US, the largest source of carbon emissions, has not ratified the protocol, partly because it imposes no limits on the gases produced by developing countries. China, which is now the world’s biggest consumer of coal and second biggest consumer of oil, emits almost as much carbon as the 25 members of the EU combined, and will shortly overtake them to become the world’s second largest source of carbon emissions, is exempt. As a result of these non-ratifications and exemptions, UN projections indicate that the treaty will reduce the currently projected rise in average surface temperature of 1.4 to 5.8°C by 2100 by just 0.1%. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Methane release - potential disaster? There are naturally-occurring greenhouse gases, mostly methane, trapped in ice-like structures called clathrates. Most of these are trapped in cold sediments and Arctic tundra. There is ~400 gigatons of methane currently trapped in frozen arctic tundra. If the temperature gets too high, and the tundra defrosts, this methane will be released. Methane is >20 times more efficient than CO² as a greenhouse gas, so this could cause ‘runaway’ climate change. Similar events have happened before. The largest previous release of methane happened at the Permian-Triassic boundary event, about 250 million years ago, when 95% of extant species were destroyed. It took 20 - 30 million years for rudimentary coral reefs to re-establish and forests to re-grow; in some areas it took >100 million years for ecosystems to reach similar levels of diversity. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Western Siberia in 2005...thawed for the first time in 11,000 years… Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies A Stern warning (part 1) Key points in the report written by Sir Nicholas Stern for the UK government, published on Monday 30th October: CO² and temperature rise • Carbon emissions have raised global temperatures by 0.5°C. • With BAU, there is >75% chance that global temperatures will rise by 2-3°C over the next 50 years. There is a 50% chance that global temperatures could rise by 5°C. Environmental impact • • • • • Melting glaciers will increase flood risk, then drought. Crop yields will decline, particularly in Africa. Rising sea levels could displace 200 million people. Up to 40% of species could become extinct. There will be more frequent extreme weather patterns. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies A Stern warning (part 2) Economic impact • A rise of 2-3°C could reduce global GDP by 3%. • A rise of 5°C could cost up to 10% of global GDP. The poorest countries would lose disproportionately more. • Worst case scenario; the global economy could shrink by 20% - permanently. Cost of remedial action • Controlling this risk would require stabilizing emissions within the next 20 years then reducing by 1-3% pa. The transition to a low-carbon economy would cost 1% of GDP, mostly one-off expenditure (e.g. investment in low-carbon technologies). Conclusion: • A one-off investment of $1 could avert a permanent reduction in annual income of $5-20. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies The real problem…as always… …is people… Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • • Surging demand Transport still only accounts for 14% global emissions, less than power generation and land-use. However, air travel is the most rapidly-growing source of carbon emissions. This growth in the demand for global transport (driven by falling prices and increasing demand) is now seen as one of the most intractable problems in slowing the rate of climate change. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • Growth in air travel Air traffic has been expanding at nearly 250% of average economic growth rates since 1959. The current UK Government's Aviation White Paper notes that aviation has increased fivefold over the last 30 years, and predicts that UK passenger numbers will more than double from 180 million to 475 million over the next 25 years. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • • Carbon-intensive activity Air travel is not only the most rapidly-growing source of carbon emissions, it is also very energy-intensive. For example, a Boeing 747 burns about 5 gallons per mile, so a London to New York flight (3,471 miles) requires some 17,355 gallons. Air travel relies on carbon-based fuel, so it is a carbonintensive activity – more so than other forms of transport. For example, a short flight (under 500km, e.g. London to Amsterdam) generates 0.17kg of carbon/passenger/kilometre, compared with 0.14 kg/km by car, 0.052 kg/km for rail and 0.047 kg/km by ship. So flying produces over three times more carbon/kilometre than rail, and over three-and-a-half times more than travelling by ship. As a result, a return flight between the UK and Australia produces about 3 tonnes of carbon per person (for comparison, an average car emits about 6 tonnes of carbon per annum). Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • Aggregate carbon emissions The world fleet now consists of about 16,000 commercial jet aircraft. These generate over 600m tonnes of CO² per year. This means that aviation generates now nearly as much CO² as all human activities in Africa. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • Consuming the carbon allowance In September 2005 the UK's Tyndall Centre for Climate Change calculated that all householders, motorists and businesses in the UK would have to reduce their CO² emissions to zero if the aviation industry was to be incorporated into the UK Government climate change targets for 2050. In other words, the entire UK economy would have to emit no carbon at all, because the airline industry would be emitting so much that it would consume the UK’s entire carbon allowance. The same equation is true of most other EU member states. This is clearly impossible. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • • Technological options? There have been significant improvements in aircraft and engine technology. The new generation of planes (like the Airbus A380 and the Boeing 7E7) are partly made of carbon composites, rather than metal, therefore offer significantly better fuel efficiency and reduced emissions per passenger. But the IPCC point out that these gains will be erased by the projected growth in demand, which means that total fuel consumption and emissions of e.g. carbon dioxide, water vapour, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide will continue to rise. It is not (yet) possible to operate aircraft on biofuels (but do we have enough land anyway?) Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Scarcity is dynamic Scarcity reflects four main factors: Total physical quantity in available form/location. Technology required to find, extract, process and transport the resource. Pattern of demand/use (also partly determined by available technology). Economics: (anticipated) demand, supply, competition, alternatives & substitutes. These four factors determine energy & resource-use efficiency. So calculations of sustainability must take into account a number of factors, including (a) total stock, location and accessibility (b) available technology, (c) economics (d) market and technological trends, (e) development trends (f) demand growth and so on. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Solutions Faster technological advance, including both incremental gains and more radical substitutions. Faster progress in ‘offset’ (flanking) technologies. Demand-rationing, via price. Command-and-control, via regulation. Disaster preparedness, zoning, planning, exercises and mitigation. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies • • • Conclusions We need a robust process for making, implementing and monitoring policy. This has to be based on strategic/scenario planning and risk mapping. We need to search for the optimal (attainable, achievable or affordable) solution; this might lie in another discipline or jurisdiction. Professor Anthony Clayton, University of the West Indies Thank you !