Invention/Discovery

advertisement

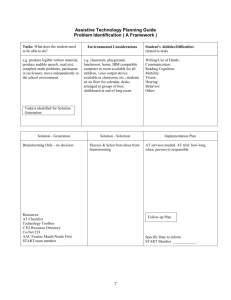

The Writing Process Everyone has a writing process. What is yours? Show Me Create a visual of your process. •A sketch •A flow chart •A collage Label some of the phases or parts of your process. Here’s how I see my process: Discovery Brainstorm Free Write Thinking Drafting Looping Focus Focus Free Write Sometimes I go back into discovery Sharing Talking Thinking Shaping Drafting Limiting Developin g Drafting Revising Shaping Revising Writing Thinking Editing Polishing Sharing Reflecting Which of these are part of your process? Discovery and Invention Collection Shaping and Limiting Organizing Drafting Revising Polishing What else do you call the parts of your process? Look over your writing process visual. Circle the parts that give you the most difficulty.* Now you can add anything you might have forgotten. Use a different color pen or font to make the changes. *Keep in mind that throughout the semester there will be other workshops that can help you in specific areas. Discovery Brainstorm Free Write Thinking Drafting Insert Looping Focus Focus Free Write Sometimes I go back into discovery Shaping Revising Writing Thinking Add: Organizing Add: Starting Over image Add Research Editing Polishing Sharing Sharing Talking Thinking Shaping Drafting Limiting Developin g Drafting Revising Add: Cutting and Pasting Reflecting Someone Else’s Process Might Look Like This: Ordering Shaping Limiting Seeing what you have Focusing Thesis Drafting Topic Audience Purpose Gathering Information Discovery & Invention Research Field Online Library Peer Sharing Revising Audience PERMISSION TO BE MESSY…OR NOT Whatever your process, remember that you have permission to move about. To To To To To be messy…or neat. start over…or not. go back to collecting data during revision. cut and paste…to reorder put back the order. Why do we study our writing process? Make a list of reasons you think it is important to studying the writing process. 1. ________________________________ 2. ________________________________ 3. ________________________________ 4. ________________________________ Here are some of my reasons: To help me see what I think. To help me uncover and discover ideas. To help me think critically about the world. To help me exercise my creativity. To help me organize and give shape to my ideas. To help me understand how purpose and audience influence my writing. To create a shared vocabulary for discussing writing. To help me avoid procrastination and frustration. To help me use my time effectively and efficiently. Our writing process helps us understand our relationship to ourselves, to our writing, and to each other. Writer Writing Process Product Audience Understanding our writing processes EMPOWERS us. Each of JCC’s Composition workshops is designed to help you gain a greater appreciation for your writing process while engaging in particular aspects of writing. Today’s workshop is : This Workshop is Worth 3 Hours Credit You may want to work through these activities over 2-3 weeks. For this credit you must: Complete the entire slide presentation. Comprehensively complete all ten activities in writing. Print the final slide (select “Current Slide”) and attach that print out to your ten completed activities. Submit your activities and the printed slide to your instructor for credit. Discovery & Language We are born with a gift of language. As children we play with words and learn not only that they sound and feel differently, but that they have power. We learn that words give us access, protect us, fulfill needs, bring us joy, and that words can hurt. Long before we learn an alphabet, we express our feelings with symbols—we mark on paper, sidewalks, chalkboards, foggy bathroom mirrors, on our own bodies, and sometimes, to our parents’ chagrin, on walls, windows, and cars. For years, as children, we delight in language—we love rhyming, singing, whispering, yelling, and we begin to make our marks on the world with images and symbols. When we do come to writing we learn the power of combining symbols k r i s t y the letters come together as “Kristy” HEY! That’s me! There am I, a voice on a page! A voice different from Calvin, Amber, Jacob, and Shanandra. ACTIVITY 1 Think about when you first discovered the power of language. When discovered a voice you could speak or write, and you used your voice to say “I AM!” Take a few minutes to write an initial paragraph describing a time when writing gave you power or helped you clarify something for yourself. People scrawl words on walls, floors, ceilings, sometimes in their own blood to exercise power, to exercise voice. Activity 2 Write about a time when you felt that you could not express yourself, what was wrong? Who or what silenced you? Or…Write about when you felt that you could not write (right), what was wrong? Who or what silenced you? Write for 10 minutes. Write without stopping. Activity 2 continued Now, read what you wrote. What more would you like to add? Make some notes. List power verbs that scroll inside your head, that you wish you could use when you have lost your voice. Sometimes it is a person or several persons who may get in the way of our voices being heard. Other times, people -- our friends, colleagues, & family -- listen and affirm. In writing, these groups are called audience. Think of audience as those who hear and read your voice. Think more about how audience shapes your attitude toward writing. The relationship of writer--writing--audience Discovering Ideas Discovering Voice There are things and worlds worth exploring, worth discovering, worth sharing with others. Writing is a way to do that. We are here to help you rediscover your voice— singing, moaning, questioning, whispering, shouting, talking, ranting, praising, praying, meditating—we want you to try all of these on paper throughout the semester. Discovery Techniques Include: Freewriting Looping Brainstorming Clustering Observing and Recording Details (Journalist Questions) Dramatization Freewriting We know that you know that sometimes words don’t flow, in fact they are hard to get past our tongues, let out of our hands and onto the page, so we have an exercise where anything goes! Activity 3 There is no topic. The only thing you have to do is keep writing. You have 10 minutes. Don’t worry about making sense, about grammar or spelling, just keep writing. Invite risks, remember, no one else will see your discoveries unless you choose to reveal. When nothing comes to you, write: I CAN WRITE over and over and over until something else comes to you, or as Peter Elbow advises, write swear words, more will come. Shake Out Your Hand So, what did you think, how did it go? Try reading over what you have written. Find a line, a thought, a word you like— something that you think is more good than bad. Activity 4 Looping Take that word or phrase from the previous free write and begin a new free write for 10 minutes. Write on the ideas connected to your chosen word or phrase. T his is called Looping, it is a way to focus your writing on an idea that interests you. Focused Free Writing Focused free writing is another wonderful tool for starting personal or public writing. Like free writing, you don’t have to worry about anything except getting your ideas onto paper. Focusing on one topic makes this a bit different than just plain old free writing. Details, Images, Insights: The Offspring of Free Writing Focused free writing can be useful for starting a draft on any subject. It is very helpful in personal experience narrative writing. Free writing helps bring back rich details and images. Brainstorming The St. Martin’s Guide to Writing describes brainstorming as a listing activity. Like Free Writing, anything goes when brainstorming. Listing or brain-storming can be a great help in deciding upon a topic or subject for a paper and also for sketching out the ideas, details, and examples for a paper itself. Here are four simple things to keep in mind about brainstorming: Withhold your judgment of ideas. Do not pass judgment on ideas until the completion of the brainstorming session. Do not suggest that an idea won't work or that it has negative sideeffects. All ideas are potentially good so don't judge them until afterwards. X Encourage wild and exaggerated ideas. The 'wilder' the idea the better. Shout out bizarre and unworkable ideas. See what they spark off. No idea is too wild. Quantity counts at this stage, not quality. Go for quantity of ideas at this point; narrow down the list later. All activities should be geared towards extracting as many ideas as possible in a given period. Let it flow! Keep each idea short, do not describe it in detail - just capture its essence. Here’s an example of a brainstorming that I did. The assignment was to recall events and experiences in my childhood. dying of rabies grandmother’s porch swing river bottoms spitting crackers at trains king of the mountain--levee Flooding G. Washington and the cherry fiasco hula hooops/lipstick/VW bug/nightmare Doc Herrman’s camp--sawing off my elbow Angel wings—I thought I could fly scissors and the pinafore Mrs. Hummer--fifth grade kicking her St. Francis and the Wolf of Gubio salmanders, newts, worms--terror catfish fishing Janet Mary Stealing my neighbor’s baseball uniform Christmas caroling sharing presents Uncle Alf and his spittoon--a bookie? falling into grease pit List by Martha Petry Activity 5 Try a brainstorming of your own that captures the events and experiences of a certain period in your life. Title your brainstorming with that period. For example: Childhood Rebellious Teen Courageous Adult Feel free to make up your own. Now you can reflect about these events and decide which would make an exciting narrative. Which do you remember with detail? Which of your stories has suspense and action? Consider which of these events has significance in shaping the person you are. Use brainstorming again and again for ideas to write about. More Brainstorming (again…and again) Once you select an item that is most compelling and surprising for you, that you find yourself replaying in your mind’s eye, you can do another brainstorming which will call up the details and incidents of this experience. Make that item the title of your brainstorming, and then as quickly as possible list all that you can remember. Don’t worry about chronological order, just roam and explore all that you can. My Example of a Focused Brainstorming : Doc Herrman’s camp-- sawing off my elbow Musty smell of men Green lush banks Humidity and heat Cool cinderblock and smoke Fishing nets and weaving The baseball game out front Cousins’ competition Boys against girls Catfish flapping on the riverbank Guts in buckets Assembly line skinning My incredible hit! Its soar into trees The rusty rain barrow –first base Mary reading, worrying Grandpa and his Bible The oversized rowboat Father and fishing buddies Sweat lined seed caps The Knife Honed cold in ice My elbow Fleeing among the mounted heads of deer, possum Glass eyes Crying and complaining Standing still Waiting for pain The Paw- Paw shaped lump A cancer Heat against my neck List by Martha Petry Mapping Mapping is another way to get ideas quickly on paper. Mapping often appeals to those of us who are visual learners. Like brainstorming, mapping is done quickly—a way to record key words and phrases, ideas, facts, and even questions. However, mapping also includes a way to organize or cluster the flow of these ideas. A good map will give shape to your thoughts, reveal connections, and make associations. Mapping works like this: Put the topic or subject that you are thinking about in the center of the page, and then start drawing out lines from it when an idea occurs to you. Mr. Vasco Luchi These lines will branch off, capturing the fragments of information that you already have in memory or those you think important to consider. Map by Martha Petry An initial mapping only takes about ten minutes. Activity 6 Try a mapping of your own. Select a person who you know well. Put their name in the center of your page. Create a map that shows your remembered experiences, observations, descriptions, interactions with this person. We can wander back and forth over a map and begin to capture the texture and the weight, the heft and shape of what we find significant in a character analysis, an argument. This discovery/invention technique is also useful in research writing. The following essay was developed from these illustrated strategies of brainstorming and mapping: Sample from my essay that grew from the map: Portrait of Vasco Luchi Mr. Vasco Luchi sauntered into the classroom, his tattered chemistry text tucked between his left arm and gelatinous belly roll. He fumbled for the class roster, called attendance, then decided to arrange us in alphabetical order. We all stood against the room's periphery, leaning our shoulders against the pea green concrete walls, waiting for our assigned seats. I questioned this militaristic, enforced maneuver, but thought, then, this first day of class, that there might be some reason for his madness. There were only sixty-three of us Juniors and not all of us were in the college-track. And, in fact, there was another section of chemistry, first period. My identical twin Mary was in it. To read the full text of this essay by Martha Petry go to: https://classes.jccmi.edu/educator/temp/youngellens/lla101/SampleEssays/ PortraitofVascoLuchi.doc From Early to Later Discovery Free writing, focused free writing, looping, brainstorming, mapping are all early discovery strategies. Discovery can also be used later in your writing process to further explore topics that you have already drafted. Observing and Recording Details Use your powers of observation and inquiry to dig below the surface of your topic. Use them to probe for details Try asking questions such as: The Poet William Blake called our senses the doors of perception… Great Questions for Exploring Ideas for Informative and Narrative Essays. Asking Who? What? When? Where? Why? and How? can help you probe for more information. Combined, these are discovery questions that all writers need as part of their skill set. Each journalist question, once answered, can be broken down into topical questions that help you further explore your topic. For instance, the question ‘who silenced you?’ may illicit a first response of “my second grade teacher” or “my older brother, Joe.” The next step is to dig beneath the surface of your first response. This requires a little mental sweat, but exploring some topical questions will often reveal new information that will add dimension and power to your writing. The chart on the following slide offers some examples of the type of subtopics you may want to explore when you ask who? You can create your own areas to explore as well as using these suggestions. When you make the exploration your own, you are beginning to understand what it means to ask who? Appearance Actions Events Personality Traits Describe: hair, face, work down to feet Show them eating, talking, playing sports, driving Personal history: family, religion, health, military, environment, work, ethnicity Show how he/she expresses humor, generosity, disappointment Weight, height, build. Compare their to something Compare the way he/she moves to other things Focus on what was said, who was there, how he/she sounds Describe how he/she shows leadership or responds to adversity A trait that creates a dominant impression Mannerisms and gestures. How do they move? How do they act? What dominant impression is created by what happened? How do his/her possessions mirror personality? Coordination, body language, style Reconstruct conversations. Focus on tone and feelings evoked. Like who, what is an open ended question that encourages our imaginations. It also helps us gain focus. An entire essay may evolve from asking what? The following chart offers examples of topical questions you may explore as you ask ‘what?’ As with ‘who,’ you can brainstorm the subtopics presented, separate them out, or create your own areas to explore. When you make the exploration your own, you are in full pursuit of what? Sensory Experience Meaning Categories Analysis What do you see? Look at color, shape, size… What does it mean? What class of things does it belong to? What are its causes and effects? What do you feel? Texture, weight, mass. What is its purpose? What similarities does it have? What can you compare or contrast it with? What is its taste? What does it reveal? What makes it different? What is its duration? What is its sound? What is its formal definition? What are its costs and/or rewards? What are its parts and processes? What is its odor? What is its value? What are its limits? Asking the what? question is particularly valuable in definition, informative, cause and effect, and argumentative papers. While who and what can be highly openended questions, asking ‘when ?’ means that we are curious about time. It also means we are interested in the space a certain time engenders. Like the other questions, ‘when?’ can be divided into subtopics including, but not limited to, the following: When and how often did it happen? Will it happen again? What happened before, during, and after? When are conditions right for it to happen? What are those conditions? How long did it last? When was it first noticed? Last observed? What were the characteristics at the time? Notice that ‘when?’ questions encourage us to discover relationships by ordering actions in time, for example, “After opening the heavy freezer lid, I pushed my face into the cold dark space hoping to freeze the beads of sweat multiplying on my upper lip. I wanted them to be as solid as the frozen peas and corn nibblets.” Activity 7 Brainstorm a list of a daily rituals that are important to you. Think of things that you do every day. For example, driving your car, picking up kids from school, waking up in the morning, the order in which you put on your clothes, etc. Select one you would like to explore using the What/When questions. Be as specific as possible in answering those questions. Don’t forget your senses. Activity 7 continued Now, look over the ideas you generated and craft three polished paragraphs about your ritual. Combining who, what, and when with ‘where’ can help you show action as it takes place in space over time. Use where to orient your readers, not only to the location but to the experience of the place and its significance. For instance, notice how I use space in the following excerpt from my narrative “Pass It On.” Joseph and I pulled up to the party store tucked between Sbarro’s and Carrousel Shoes. It was one of those late August days when the air hovered--stagnant and shimmering--above the melting blacktop. Stepping from the air-conditioned mini-van, it took only a few seconds before I tasted the salt of my sweat as it traced my upper lip, slipped round its edges, and trickled toward the cliff of my chin. The party store’s air conditioner was broken. The only source of air exchange, a smudged glass door, was propped open with a broken brick. The store’s dark aisles smelled damp. I opened a refrigerated cooler and chilled air teased my face and upper torso as I lifted out a sixpack of Michelob Light. Walking past displays of Fritos, Little Debbies, and Trojan Condoms, I placed the beer on the counter, dug in the pocket of my denim shorts for the few wadded bills I’d stuffed there earlier. “Six and seventy-three.” Her voice was hard, like whiskey and cigarettes. It raised my eyes. ..(from essay by kris shirk) During your exploration of ‘where?’, consider the following questions: Where did the event take place? What psychological or emotional associations does this place have? Consider place from a physical or historical perspective. What other perceptions are there of the place? Explore the shape, size, space of this place. What are the dominant sights, smells, sounds, and associations of this place? What experiences are most resonant for you in this place? Activity 8 Carefully read the example on the next slide and identify the ways the writer uses ‘where? ‘to create an experience that yields significance. Record your findings for this activity. Doc Herrmann's Camp didn't lay nestled anywhere. Rather it sat squarely, a cinderblock structure, the first camp at the end of a rutted road that ran through corn bottoms and mail pouch tobacco sheds. There were five other camps that meandered out along this lane: some wood, some asbestos shingled, some well kept, others not. Twelve miles south of Portsmouth, past South Portsmouth, Friendship, Turkey Creek, Ottway and Sugar Grove, my family drove on Sunday afternoons in summer to this place where my dad and other men fished and hunted every Thursday night, come winter or fall and the seasons in-between. The camp smelled like men: cool and dark with wood smoke and gutted fish and tobacco. Summers were always hot in southern Ohio as I remember them--a glaze of sun that squinted your eyes and mud cracks so wide along the river bank that you could put your legs knee deep into the lines, split open like fruit that had burst its skin. Doc Herrmann's camp was cool. Overhung by willows and cottonwoods, oak and ash, it just sat there, a place that calls up the words: gritty and backwoods and green. While who, what, when, and where help us discover details and relationships, how directs us toward an examination of procedures, methods, and processes. It helps us think about how stuff gets done, how it is arranged, and how it best to do it. As with ‘who,’ you can explore the topical questions presented on the next slide, separate them out, or create your own areas to explore. When you make the exploration your own, you are in full pursuit of what? How does it get done? Record the processes, the goals of processes, the pitfalls of the processes. How is it done? Record steps & procedures. How important is order? Is there a level of difficulty associated with it? How is success measured? How would you describe the process? Is it primarily natural, mechanical, mental, or physical? What does this process resemble? As you explore topical questions with ‘how?’ as well as with the other journalist questions, keep your reader’s needs in mind. What do your readers need or want to know? What does having or not having information do to the impact of your message? When children are young, ‘why?’ is one of their common questions. Kids are smart, they hone in on the question that asks for explanations, reasons, and the thought behind the statement. Asking and then answering ‘why? questions are what creates meaning and significance in your paper. Another way to think about why is to consider a reader’s asking “So What?” ‘Why questions ask us to analyze and explain actions or processes. They ask for reasons and conclusions. They help us to be specific and to show more than tell. Use the topical questions presented on the next slide to explore the ‘why’ of your topics. You may separate them out, or create your own areas to explore. When you make the exploration your own, you are in full pursuit of ‘why?’ For more information about this essential question, please see the Workshop “Making Meaning.” Why did it happen? How can we recognize the cause? Is there more than one cause? Which cause is more important? What motives are behind it? Which are easy to see, which are hidden? What are the results? Where they intentional or accidental? Why didn’t something else happen? A Word of Caution: Be judicious when exploring your topic with the journalist questions. The depth of your explorations will depend on your audience’s needs and interests as well as your purpose for writing. Consider how much you want your reader to know and how the information you offer will successfully fulfill the purpose and add significance to your writing. Activity 9 Examine the paper you are currently working on. Write a reflective statement that captures the paper’s significance for both yourself and your audience. In other words, What? do you want your readers to understand? Why? is the topic important to you? How? have you used journalistic questions to develop a better understanding of your topic? You may have noticed by now that using who, what, when, where, why, and how lead to discoveries that lend detail, focus, and shape to your writing. Throughout the semester, we encourage you to play with the journalist questions and to always keep open the doors of your perception. With Dramatization Sometimes all of us face the terror of the blank page, when written words just do not come. It’s like knowing you are going to hit a wall. Whether you’re accelerating or putting on the brakes so that the crash isn’t fatal, you still have that feeling that you can do nothing, say nothing, write nothing to prevent the wall’s impact. This is writer’s block. Whenever you feel stuck --at any stage of your process,-You can… With Dramatization Dramatization is a method of discovery and invention that can help overcome writing inertia. Dramatization. simply means telling our stories aloud. sharing our portraits of people, explaining our subjects of investigation, and making our arguments. And doing it out loud. Implicit, is the fact that you tell your story to someone willing to listen. This is akin to having a reader for your paper. The listener, however, can AND SHOULD interrupt. The listener’s questions can help you as a writer to know; Where you need more information If your story makes sense Where you can provide sensory description, facts, examples, suspense, or reasons Where you need to clarify meaning If you have had an impact on your audience Free Your Mind: Choose Discovery Discovery Brainstorm Free Write Thinking Drafting Looping Focus Focus Free Write Sometimes I go back into discovery Shaping Revising Writing Thinking Editing Polishing Sharing Sharing Talking Thinking Shaping Drafting Limiting Developing Drafting Revising Reflecting And use it often. Remember, in our recursive writing processes, invention and discovery occur in all stages. Activity 10 Now that you have spent some time in this workshop, answer the following questions: What new ideas were presented? What was reinforced for you? Which strategies did you find most helpful and why? What do you want to learn next? Where do you go from here? Discovery and Invention Workshop Designed by: Martha Petry and Kris Shirk of JCC’s composition faculty. To Receive 3 Hours Credit for This Workshop Complete the entire slide presentation. Comprehensively complete all ten activities in writing. Print this final slide (select “Current Slide”) and attach that print out to your ten completed activities. Submit to your instructor for credit.