August 12th, 2003 as a powerpoint file (requires Powerpoint)

advertisement

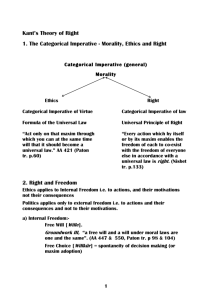

Today’s Lecture • • • • • Grade spreadsheet Turnitin.com Study session on Monday 18th Final Exam and office hours Immanuel Kant Grade spreadsheet • I will be placing an undated grade spreadsheet on the course website some time on Wednesday. Please check to ensure that the data matches what you have (this will be the last chance to do so before the exam). • If there are any discrepancies, come and see me. Turnitin.com • Remember that if your assignments are not in Turnitin.com by Friday you will receive a zero on the relevant assignment. • There is no negotiation on this one, so don’t leave this task to the last minute. Study session on Monday 18th • There will be a study session on Monday the 18th, from 1100-1300 (or 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m.). This will be held in Talbot College room 310. You don’t have to stay for the whole period, if you come at all. Attendance is strictly voluntary. But you may be able to help each other out. • Bring ideas and talk stuff over. I won’t be able to give you any substantive answers, as that would defeat the purpose of the exam. But I can referee your discussion (i.e. if you need a referee). Final Exam and office hours • Don’t forget that the final exam is on Tuesday, the 19th, at 9:00 a.m. • The location, remember, is TC 343. • Also, I will choose the exam questions from the first fifteen questions on your original handout of possible exam questions (unfortunately we will not be getting to either Rawls or hooks - so drop questions 16 and 17). • My final office hours for this course are this week. I will be submitting your final grades on Friday the 22nd, so if you have any questions about grades, seek me out before the 22nd. First Section: Intrinsic versus extrinsic goodness or value • You can understand the beginning of this section as assuming that the moral life is good. This is suggested by the status accorded those who would live morally (see FP, p.643). The question is, Is it extrinsically or intrinsically good? First Section: The good will • Under the influence of something like this consideration, Kant introduces the notion of the good will. • It is his contention that “[n]othing in the world indeed nothing beyond the world - can possibly be conceived which could be called good without qualification except a good will” (FP, p.642). • As he implies in this claim, he will include God here. First Section: The good will • Kant considers candidates for unconditional goods (i.e. unqualified goods) among those personal traits associated with valuers, and with those environmental contingencies that inform the quality of their lives. He seems to treat this as exhaustive in its scope. • Neither the “talents of mind” (FP, p.642) nor the “qualities of temperament” (FP, p.642) can be taken to be unconditionally good. • If it were not for the goodness of will, or character, such qualities as intelligence or perseverance could do great harm. Their goodness, then, is derivative (FP, p.643). First Section: The good will • “[G]ifts of fortune” (FP, p.643) by which he means “[p]ower, riches, honor, ... health, general well-being and the contentment with one’s condition” (FP, p.643) are also derivatively good. Without a good will, or character, such ‘gifts’ could do great harm (FP, p.643). • This does not yet give what Kant wants, after all the good will could be extrinsically good. • But it is Kant’s contention that the will is not good because of what it accomplishes or because of its causal potency (i.e. it is not good for something else, or achieving something else). Indeed its goodness would not be diminished if it were to lack causal potency. “[I]t is good only because of its willing (i.e., it is good in itself)” (FP, p.643). First Section: An(other) argument for the intrinsic goodness of the will • (1) Every organ has a purpose. • (2) Every organ is best fitted or adapted for its purpose. • (3) The more a person tries to use her reason to secure her own happiness the more she fails. • (4) What’s more, those who live ‘closer to instinct’ are happier than those who live according to their reason. • (5) Reason, therefore, is ill-equipped to secure an individual’s happiness. First Section: An(other) argument for the intrinsic goodness of the will • (6) Given (5), the purpose of reason cannot be a rational being’s happiness. • (7) Reason is a practical faculty (or power)...that is, reason is a faculty (or power) for influencing the will. • (8) If reason’s goodness (or value) lies in its purpose, then it lies in its influence on the will. • (9) Given (3) through (6), reason’s goodness (or value) isn’t in its power to yield an extrinsically good will. • (10) Therefore, reason’s goodness (or value) must lie in its power to yield an intrinsically good will (FP, pp.643-44). First Section: Developing the notion of an intrinsically good will • It is at this point that Kant begins his discussion of duty. The reason for this is that the notion of duty implies a good will. I.e. to act from duty is to exhibit a good will (FP, p.644). • He hopes, then, by developing the notion of what it is to act from duty, he will, ipso facto, develop the notion of a good will (FP, p.644). First Section: The first proposition • The moral worth of an action lies in the intentions of the agent. If the agent acts because duty requires her to so act, then her action has moral worth (FP, pp.644-45, 646). • An action motivated by self-interest, self-preservation or even feelings of warmth towards another lack moral worth, according to Kant (FP, pp.644-45). • This may seem strange at first, but Kant notes that the (albeit meager) moral worth of such actions only arises when they accord with our duties. But since such inclinations do not always so arise, they are not unconditionally good, and only what is unconditionally good has moral worth (FP, p.645). First Section: The first proposition • “It is in this way, undoubtedly, that we should understand those passages of Scripture which command us to love our neighbor and even our enemy, for love as an inclination cannot be commanded. But beneficence from duty, even when no inclination impels it and even when it is opposed by a natural and unconquerable aversion, is practical love, not pathological love - it resides in the will and not in the propensities of felling, in principles of action not in tender sympathy; and it is alone can be commanded” (FP, p.646). First Section: The second proposition • “An action done from duty does not have its moral worth in the purpose which is to be achieved through it but in the maxim whereby it is determined” (FP, p.646). • This seems to follow from Kant’s earlier rejection of the view that an action’s moral worth arises from the purposes or ends of said action. Though an action’s effects/consequences or purposes may conform to what is right, the wrong motivation for said action can undermine its worth. What ensures the proper connection between an action and what’s right is the principle of the will that gives rise to the action (FP, p.646). First Section: The second proposition • Interestingly, the success or failure of the willed action is irrelevant to its moral worth (on this account). Whether it succeeds or fails is largely out of the hands of the person willing the action. The goodness of a person’s choice can only be reasonably ascribed, then, on other grounds, grounds over which the person has control. Thus the choice itself is the source of the moral worth of an act (if it has any moral worth at all) (FP, p.646). First Section: The third proposition • “Duty is the necessity to do an action from respect for law” (FP, p.646). • You have three elements in the notion of ‘acting from duty’: (1) An objective principle (or practical law), (2) a subjective maxim which accords with, or follows from, said objective principle and (3) respect for the law (without any regard for the consequences of acting in accord with said law) (FP, p.647). First Section: practical laws, objective principles and maxims • An objective principle is that which all rational beings (human or otherwise) could act upon if their reason has control over their desires. • A maxim is a subjective principle of the will...that is, a principle with which an agent wills herself to act (i.e. a psychological principle of action). • An objective principle is a practical law (see FP, pp.634, 637 and also the author’s footnote on page 647 of your FP). • Note that, due to the abstract nature of duty and the moral law, only a rational being can be moral (FP, p.647). This will exclude children by the way (they are still too bound to contingencies and lack the ability to reflect without recourse to experience). First Section: The first categorical imperative • The supreme categorical imperative is proffered as a way of discovering what counts as an objective principle (or practical law). • Also, what he identifies as the supreme categorical imperative, of which there are at least three complementary versions, is to be imagined as lying at the foundation of our moral system. First Section: The first categorical imperative • Those imperatives that we use (or pretend to use) in our moral lives are derived from the supreme categorical imperative (FP, p.647). • “The common sense of mankind in its practical judgments is in perfect agreement with this and has this principle constantly in view” (FP, p.647) • The derivation of lower order imperatives from the supreme categorical imperative is thought to preserve the necessity enjoyed by the supreme categorical imperative. First Section: The first categorical imperative • The first categorical imperative is: “I ought never to act in such a way that I could not also will that my maxim should be a universal law” (FP, p.647). • This falls out of Kant’s move to strip “the will of all impulses which could come to it from obedience to any law, nothing remains to serve as a principle of the will except universal conformity to law as such” (FP, p.647). First Section: The first categorical imperative • Consider Kant’s test case: “May I, when in distress, make a promise with the intention not to keep it?” (FP, p.647). • Kant suggests we can distinguish a prudential and strictly moral approach to answering this question. • Prudentially, we can go either way (FP, p.648). • Morally, however, we can only go in the direction of not making such a promise (at least according to Kant) (FP, p.648). • After all, if we imagine such a maxim holding as a universal law, no promises could subsequently exist. No one would trust me, nor could I trust them, so promises would be of no effect. Since I cannot so will my maxim to be a universal law, I ought not to follow it myself (FP, p.648). First Section: The first categorical imperative • Note that, for Kant, his account thus far accords, or purports to accord, with our common moral knowledge (FP, pp.64849). • Kant does not view the discussion thus far as innovative, he has merely highlighted what is already at work in our moral reasoning (FP, p.648). • We have an imperative that yields maxims which hold universally. • We have an imperative that yields maxims which hold impartially. • We also have a method of discovering our duty which does not require theoretical knowledge, a wealth of experience or intellectual expertise (FP, p.648). Second Section • In this Second Section, Kant will move from a critical examination of our common moral knowledge, to a metaphysics that will explain or make sense of this knowledge. Second Section: Kant’s pessimism • Kant opens the second section up with the admission that “[i]t is, in fact, absolutely impossible by experience to discern with complete certainty a single case in which the maxim of an action, however much it might conform to duty, rested solely on moral grounds and on the conception of one’s duty” (FP, p.650). Second Section: Kant’s pessimism • This is primarily to indicate that Kant’s notion of duty is not an empirical notion. That is, Kant didn’t merely glean his theory of duty from what can be observed in common moral practice (FP, p.650). • It also indicates that, for Kant, the success or failure of his theory does not depend on whether we can successfully implement it (see page 650 of your FP). • Is this a problem? Second Section: Kant’s pessimism • “Our concern is with actions of which perhaps the world has never had an example, with actions whose feasibility might be seriously doubted by those who base everything on experience [i.e. empiricists], and yet with actions inexorably commanded by reason. For example, pure sincerity in friendship can be demanded of every man, and this demand is not in the least diminished if a sincere friend has never existed, because this duty, as duty in general, prior to all experience lies in the idea of reason which determines the will on a priori grounds” (FP, p.650). Second Section: Kant’s pessimism • Think of this another way: Kant is committed to the view that the a priori demands of reason are there to be discovered, but this does not mean that all or any rational beings will do so. • Isn’t something like this readily conceded by anyone who believes that there is an objective ground to morality, and that there is a distinction to be made between what we do and what we ought to do? Second Section: Against the situatedness of moral principles • (1) Moral laws must be valid universally. (This Kant takes to be fundamental to an understanding of the nature of morality). • (2) From this it follows that, where there is a moral agent, s/he or it ought to act in accord with the moral laws. • (3) From this it follows that the moral laws are not grounded in those properties that make a particular moral agent human or nonhuman. • (4) It must also be the case, then, that the moral laws are not grounded in particular (or localized) circumstances or cultures. • (5) Therefore, no set of experiences, no set of empirical facts, can ground or entail the moral laws (FP, p.651). Second Section: Against the situatedness of moral principles • For Kant, if we try to ground our moral principles/laws on our nature, or in our moral practice, we may focus on principles or laws that only sensibly hold for humans, rather than for all moral agents. • However, if our moral principles or laws ought to hold for all moral agents, then we cannot ground our moral principles on our nature or moral practice (FP, pp.651, 653). • This leaves nowhere else to go than pure reason, according to Kant (FP, p.651). Second Section: Against the situatedness of moral principles • “But a completely isolated metaphysics of morals, mixed with no anthropology, no theology, no physics, or hyperphysics, and even less with occult qualities (which might be called hypophysical), is not only an indispensable substrate of all theoretically sound and definite knowledge of duties; it is also a desideratum of the highest importance to the actual fulfillment of its precepts” (FP, p.652). Second Section: categorical and hypothetical imperatives • Hypothetical imperatives are conditionally necessary. Given a certain end (whether it is currently willed or not), one should act according to a certain principle (which will enable one to achieve that end) (FP, p.654). • Think of a hypothetical imperative as an if...then proposition. E.g. if you want to drive to university this morning, then you need to make sure there is enough gas in the car. Second Section: categorical and hypothetical imperatives • Categorical imperatives are unconditionally necessary. That is, the imperative is not conditional on a certain end being willed (FP, p.654). • It is clear from what has already been covered that moral laws, under Kant’s account, are categorical imperatives (see FP, p.655). Second Section: categorical and hypothetical imperatives • Kant will also contend that the content of the supreme categorical imperative from which our moral laws follow, can be deduced from the “mere concept of a categorical imperative” (page 658 of your FP). • This, of course, must be the case if the supreme categorical imperative is to hold for all rational beings (be they human or nonhuman, in our solar system or elsewhere)...right? Second Section: categorical and hypothetical imperatives • “But if I think of a categorical imperative, I know immediately what it will contain. For since the imperative contains, besides the law, only the necessity of the maxim of acting in accordance with the law, while the law contains no condition to which it is restricted, nothing remains except the universality of law as such to which the maxim of the action should conform; and this conformity alone is what is represented as necessary by the imperative” (FP, p.658). Second Section: the supreme categorical imperative • Since the supreme categorical imperative requires that all rational beings act in accord with it, without restrictions, the content of this imperative must be universal in scope. • There is also only one categorical imperative. • Thus: “Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law” (FP, p.658). • All other moral imperatives are derived from this principle (FP, p.658). Second Section: the second version of the categorical imperative • “Act as though the maxim of your action were by your will to become a universal law of nature” (FP, p.658). • This, for Kant, captures the necessity attached to the supreme categorical imperative (FP, p.658). Understand it as a way of imagining a universe in which all rational agents perfectly follow the dictates of their reason. • Also note how he is more explicitly introducing the notion of autonomy (or self rule). • So understood such a law seemed to nicely mirror, in Kant’s view, the relationship between natural objects and the laws of nature (FP, p.658). Second Section: the second categorical imperative • Note in Kant’s examples of how to apply his procedure of deciding our duty there are two different ways in which we appear to run into trouble if we depart from what can be willed as a universal law. • (1) What we propose to do may, if universalized, ‘selfdestruct’ (examples 1 and 2 [FP, pp.658-59]). • (2) Even if what we propose to do does not ‘self-destruct’, it may be the case that we still cannot sincerely will it to be a universal law (examples 3 and 4 [FP, p.659]). Second Section: the second categorical imperative • • • • Example 1: The Suicide Candidate (FP, pp658-69). Example 2: The False Promise Maker (FP, p.659). Example 3: The Talented (But Lazy) Person (FP, p.659). Example 4: Selfish, and Unscrupulous, Rich Person (FP, p.659). • What do you think of his examples? Does his fourth example deal with Glaucon’s concerns in our previous readings? • What of his earlier claim, in connection to false promising, that “[i]mmediately I see that I could will the lie but not a universal law to lie” (FP, p.648)? • Are there counter-examples of morally acceptable lies? Second Section: the second categorical imperative • Note that in all of his examples, Kant seeks to infer our moral duties from the Supreme Categorical Imperative (FP, p.659). • “The foregoing are a few of the many actual duties, or at least of duties we hold to be actual, whose derivation form the one stated principle is clear” (FP, p.659). Second Section: on transgression • Kant suggests that when we shirk our moral duty we do not do so by not willing that our maxims become universal laws. Rather, we take the liberty of viewing ourselves as the exception, even if only ‘momentarily’ (FP, p.660). • Is he right? Second Section: Rational beings as ends in themselves • The third version of the supreme categorical imperative rests on a recognition that each of us, when we will an action, treat ourselves as ends in ourselves ... not merely as means. Since we could not (without contradiction) will ourselves to be regarded as means only, we ought not to treat other rational beings in this way (FP, p.662). • This is true whether we talk of hypothetical or categorical imperatives (FP, pp.661-62). • This Kant contends, is a duty of every rational agent (FP, p.662). • The ‘third version’ reads: “Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of another, always as an end and never as a means only” (FP, p.662).