10Lisbon - Douglas Walton's

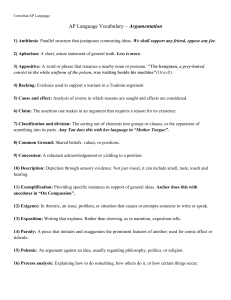

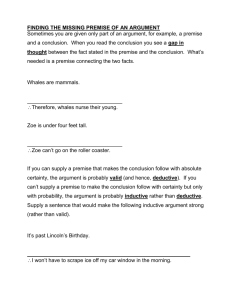

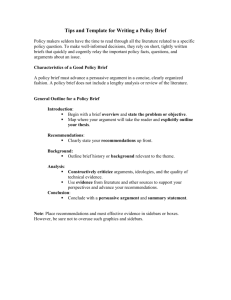

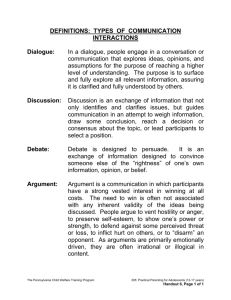

advertisement

The Current Agenda of Argumentation Theory Talk at New University of Lisbon, February 10, 2010, 11:00 am, Room 1.05, Building I&D. Web page with pdf papers: http://dougwalton.ca Douglas Walton: University of Windsor Assumption Chair in Argumentation Studies Distinguished Research Fellow of CRRAR Centre for Research in Reasoning, Argumentation & Rhetoric CRRAR and Assumption CRRAR Mission Statement The mission of the Centre for Research in Reasoning, Argumentation and Rhetoric is to be a national and international leader in individual and collaborative research into the theory and practice of reasoning, argument and argumentation, and rhetoric from the perspective of all related academic disciplines, and a leader in the application and dissemination of this research. CRRAR is also the home of the journal Informal Logic. My position at CRRAR is that of Distinguished Research Fellow. I also hold the Chair of Argumentation Studies at Assumption University, a college in the University of Windsor. Assumption was founded by the Basilian Fathers in 1870 as part of Assumption University, which is now part of the University of Windsor. What is an Argument? An argument is a social and verbal means of trying to resolve, or at least contend with, a conflict or difference that has arisen between two parties engaged in a dialog by eliciting reasons on both sides (Walton, 2007). According to this definition, an argument necessarily involves a claim that is advanced by one of the parties, typically a claim that the one party has put forward as true, and that the other party questions. Arguments have premises and conclusions, they can be of different kinds, they can be stronger or weaker (have weights), and different standards of proof can be required of them in different contexts of use. Deductive Argument Premise: Luigi is an Italian soccer player. Premise: All Italian soccer players are divers. Conclusion: Luigi is a diver. It is logically impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false. But is the first premise true? Inductive Argument Premise: Luigi is an Italian soccer player. Premise: Most Italian soccer players are divers. Conclusion: Probably Luigi is a diver. It is improbable for the premises to be true and the conclusion false. Wigmore (1931, p. 20) considered arguments of a kind that are commonly used in collecting evidence in law. Last week the witness A had a quarrel with the defendant B, therefore A is probably biased against B. A was found with a bloody knife in B’s house, therefore A is probably the murderer of B. Deductive, Inductive, and the 3rd Type: Abductive? Clue: Backward Reasoning by Explanation? Defeasible Reasoning Birds fly. Tweety is a bird. Therefore Tweety flies. Subject to exceptions (Tweety = penguin). Based on non-absolute generalizations. Nonmonotonic: valid arguments can become invalid by adding premises. Typical Argumentation Schemes Common schemes include such familiar types of argumentation as argument from expert opinion, argument from lack of knowledge, argument from example, argument from a rule to a case, argument from a verbal classification, argument from position to know, argument from analogy, argument from precedent, argument from correlation to cause, practical reasoning, abductive reasoning, argument from gradualism, and the slippery slope argument. Other schemes that have been studied include argument from waste (also called sunk costs argument), argument from temporal persistence and argument from appearance. In addition to presumptive schemes, it is possible to treat deductive and inductive forms of argument as schemes. All are linked arguments. Deductive Linked Argument Defeasible Linked Argument Competence Center ELAN Fraunhofer FOKUS The Carneades Model of Argument Carneades models the structure of arguments the acceptability of statements burdens of proof (questioning, production and persuasion) proof standards, such as preponderance of the evidence Carneades is a computational model: the functions of the model are all computable (i.e. recursive, decidable) Carneades has an argument mapping tool with a graphical user interface: http://carneades.berlios.de/ Many Argumentation Support Tools Scheuer, O., Loll, F., Pinkwart, N. & McLaren, B.M. (2010). ComputerSupported Argumentation: A Review of the State of the Art. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning. 5(1). Two of them are Carneades and Araucaria. Rationale is another one that can be very useful for philosophers. Carneades (c.213 - c.128 B.C.) Leader of the Academic Skeptics. Head of Plato’s (third) Academy. Developed a theory enabling human action despite the lack of perfect knowledge, based on “reasonable grounds” and “probable” inferences. Carneades’ notion of probability corresponds closely to what is now called defeasible, plausible, or nonmonotonic reasoning. Competence Center ELAN Linked Arguments Fraunhofer FOKUS Competence Center ELAN Convergent Arguments Fraunhofer FOKUS Competence Center ELAN Serial Arguments Fraunhofer FOKUS Competence Center ELAN Pros and Cons Fraunhofer FOKUS Araucaria Araucaria is a software tool for analyzing arguments. It aids a user in reconstructing and diagramming an argument using a simple point-andclick interface. The software also supports argumentation schemes, and provides a user-customizable set of schemes with which to analyze arguments. Once arguments have been analyzed they can be saved in a portable format called AML, the Argument Markup Language. http://www.computing.dundee.ac.uk/staff/creed/araucaria/ Argument from Expert Opinion Major Premise: Source E is an expert in domain D containing proposition A. Minor Premise: E asserts that proposition A (in domain D) is true (false). Conclusion: A may plausibly be taken to be true (false). Application to Law Currently one of the most active areas of application is to law. Researchers in AI and Law are prominent users of argumentation tools, including Tom Gordon, Bart Verheij, Henry Prakken, Trevor Bench Capon and Floris Bex. Scheme from Expert Opinion Corroborative Expert Opinions: Linked and Convergent Arguments Six Critical Questions Expertise Question: How knowledgeable is E as an expert source? Field Question: Is E an expert in the field D that A is in? Opinion Question: What did E assert that implies A? Trustworthiness Question: Is E personally reliable as a source? Consistency Question: Is A consistent with what other experts assert? Backup Evidence Question: Is E’s assertion based on evidence? Legal Expert Opinion Scheme Competence Premise (Ordinary Premise): E is an expert in knowledge domain D. Statement Premise (Ordinary Premise): E said the sentence S*. Interpretation Premise (Ordinary Premise): S is a reasonable interpretation of S*. Domain Premise (Assumption): S is in D. Depth of Knowledge Premise (Assumption): The knowledge of E about D is deep enough to know about S. Careful Analysis Premise (Assumption 3): E’s testimony S* is based on his own careful analysis of evidence in this case. Other Experts Premise (Exception): S is inconsistent with what other experts in D say. Credibility Premise (Exception): E is not credible. Conclusion: S may plausibly be taken to be true. Scheme for Practical Reasoning Major Premise: I have a goal G. Minor Premise: Carrying out this action A is a means to realize G. Conclusion: Therefore, I ought (practically speaking) to carry out this action A. Critical Questions for Scheme CQ1: What other goals do I have that should be considered that might conflict with G? CQ2: What alternative actions to my bringing about A that would also bring about G should be considered? CQ3: Among bringing about A and these alternative actions, which is arguably the most efficient? CQ4: What grounds are there for arguing that it is practically possible for me to bring about A? CQ5: What consequences of my bringing about A should also be taken into account? Lunesta Sleep Medication Ad The picture in the ad shows the head and shoulders of a young man asleep, his head resting against the pillow. In large print above the picture, the words “The sleep you’ve been dreaming of.” are printed. Below the picture it says, “Soothing Rest for Mind and Body.” Below that, the text of the ad appears [as quoted]. “It’s what you’ve been craving. Peaceful sleep without a struggle. That’s what Lunesta is all about: helping most people fall asleep quickly, and stay asleep all through the night”. Premises of Lunesta Argument Premise: my goal is to have peaceful sleep without a struggle. Premise: taking Lunesta is the best means to have peaceful sleep without a struggle. Premise: Lunesta helps most people fall asleep quickly. Premise: they stay asleep all through the night. Argument Map of Lunesta Ad Enthymemes An enthymeme is an argument with an implicit premise or conclusion. All physicians are college graduates, so all members of the AMA are college graduates. MISSING PREMISE: All members of the AMA are physicians. Roadside sign: “The bigger the burger, the better the burger. The burgers are bigger at Burger King.” MISSING CONCLUSION: The burgers are better at Burger King. In the Lunesta ad, the conclusion is also implicit. Normative Models of Dialog Arguments are taken in traditional logic, to consist of a set of premises (statements) and a conclusion (another statement). The dialog is a model represents the conversational setting in which an argument was put forward for some purpose. There are different types of dialog. Each dialog has an opening stage, and argumentation stage and a closing stage. Classification of Dialogs Dialog Persuasion Critical Discussion Information Seeking Interview Negotiation Advice Solicitation Inquiry Scientific Inquiry Expert Consultation Deliberation Public Inquiry Eristic Quarrel Types of Dialog TYPE OF DIALOG Persuasion INITIAL SITUATION Conflict of Opinions Need to Have Proof Conflict of Interests PARTICIPANT’S GOAL Persuade Other Party Find and Verify Evidence Get What You Most Want GOAL OF DIALOG Information- Need Seeking Information Acquire or Give Information Resolve or Clarify Issue Prove (Disprove) Hypothesis Reasonable Settlement that Both Can Live With Exchange Information Deliberation Co-ordinate Goals and Actions Decide Best Available Course of Action Verbally Hit Out at Opponent Reveal Deeper Basis of Conflict Inquiry Negotiation Eristic Dilemma or Practical Choice Personal Conflict Dialogue Structure Salmon’s Case Salmon sold medicines in London. M’Kensie bought from him some pills for rheumatism; after numerous doses he died. The medical men, on a postmortem examination, affirmed that certain ingredients of these pills had caused his death; and Salmon was indicted for manslaughter. But on the trial he produced many witnesses, who had taken the same kind of pills with much benefit; one witness affirmed that he had taken twenty thousand of them within the past two years, to his great benefit! If these circumstances were true, the inference was inevitable that the pills were not lethal. But was the testimony to this circumstance true? Key List of Statements in Salmon’s Case (A) The medical man affirmed that certain ingredients of the pills had caused M’s death. (B) The medical man is an expert in medicine [implicit premise]. (C) Certain ingredients in the pills had caused M’s death. (D) M’s taking the pills caused his death. (E) Witness W testified that he took the same kind of pills and they caused him no harm. (F) Witness W is in a position to know about the effects of the pills on him [implicit premise]. (G) If the pills caused no harm to W, the pills were not lethal [implicit premise]. (H) The pills were not lethal. Diagram of Salmon Case How Arguments are Evaluated Burdens of proof and standards of proof, along with argument weights, determine how to evaluate the argumentation in a dialog. The burden and standard of proof are set at the opening stage, and depend on the type of dialog. In the argumentation stage, each side presents reasons supporting its view and attacks the opposed view by raising critical questions and rebuttals. The burdens and standards are then applied at the closing stage to determine which side won and which lost the dialog. Defining Burden of Proof Burden of proof has three components: (a) a contained proposition representing one arguer’s claim to be proved (b) which arguer (proponent or respondent) has that thesis, and (c) a standard of proof required for proving that thesis. There are different types of burden of proof recognized in law. Two Burdens of Proof in Law Burden of Persuasion (also called legal burden of proof): in a murder trial, the prosecution must prove the charge that the defendant committed murder. Evidential Burden (also called burden of production): if a person accused of burglary is found carrying “burglarious implements”, an evidential burden is placed on him to give some explanation of why he had such articles in his possession. If he fails to do so, the conclusion can be drawn he was carrying them to commit burglary. Standards of Proof (Gordon & Walton, 2009) The standard of scintilla of evidence iff there is one argument supporting the claim. The preponderance of the evidence standard is met iff scintilla of evidence standard is met and the weight of evidence for the claim is greater than the weight against it. The clear and convincing evidence standard is met iff the preponderance of the evidence standard is met and the weight of the pro arguments exceeds that of the con arguments by some specified threshold. The beyond reasonable doubt standard is met iff the clear and convincing evidence standard is met and the weight of the con arguments is below some specified threshold. These standards are defined in the Carneades model. Locutions and Speech Acts Statements and questions are locutions. Making an assertion is a speech act. Asking a question is a speech act. Asking for an explanation is an even more specific speech act. Putting forward an argument is a speech act. Offering an explanation is a speech act. Speech Act Moves in a Dialogue Goal of Dialogue Sequence of Moves Turn-taking Respondent's Move Speech Act Post-condition Proponent's Move Pre-condition Initial Situation Speech Act Dialogue Models of Explanation The dialogue model is not restricted only to argumentation. An explanation can be modeled as a dialogue between two agents in which one agent is presumed by a second agent to understand something, and the second agent asks a question meant to enable him to come to understand it as well. The dialectical model articulates the view of Scriven (2002, p. 49): “Explanation is literally and logically the process of filling in gaps in understanding, and to do this we must start out with some understanding of something.” Argument or Explanation? Test to judge whether a given text of discourse contains an argument or an explanation. Take the statement that is the thing to be proved or explained, and ask yourself the following question. Is it taken as an accepted fact, or something that is in doubt? If the former, it’s an explanation. If the latter, it’s an argument. The Goal of Dialogue is Different The purpose of an argument is to get the hearer to come to accept something that is doubtful or unsettled. The purpose of an explanation is to get him to understand something that he already accepts as a fact. Conditions in the Dialogue Model Dialogue Conditions: explainee asks question of a specific form asking about what is assumed to be a known fact S. Understanding Conditions: explainee does not understand S, but assumes that explainer understands S. Success Conditions: explainer by what she says brings the explainee to understand S. Rules for Explan Dialogue System Opening: when explainee makes an explanation request for S (accepted fact). Locution Rules: defines different speech acts (kinds of moves) that are allowed. Dialogue Rules: show which move must follow each previous kind of move. Success Rules: show when transfer of understanding has been achieved. Closing1: when explainee says ‘In understand it’. Closing2: explainee shows understanding through testing. Explanation in a Sequence of Dialogue Event Taken as Factual by Both Parties Attempt Judged to be Successful or not by Respondent Something Perplexing to Respondent about Event Not Successful Explanation Dialogue Concluded Respondent asks Proponent for Help in Understanding Successful Proponent Offers Explanation Attempt References