- Surrey Research Insight Open Access

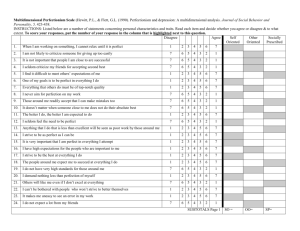

advertisement