Misinterpretation of Values

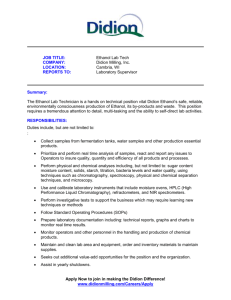

advertisement

Misinterpretation of Values Peter Simon AP English 11 October 18, 2009 In her essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” Joan Didion claims that “the center was not holding” (84). Traditional values of early to mid-twentieth century society were being abandoned by troubled youths in pursuit of true meaning and purpose. Their parents, who themselves had lost confidence in accepted belief, had neglected to teach them the “rules” of their society. In Didion’s essay “On Morality,” she dissects the growing misinterpretation of values resulting from this social movement. According to Didion, morality has little to do with the “ideal good,” as many had come to understand it, but rather with the promises that we make to ourselves and to each other. Following WWII, morality became something that many fell back on, offered as an explanation to their actions. In reality, people were deceiving themselves, which hinted to the “mass hysteria” that was already being heard throughout the land. Didion’s observation that “the center was not holding” continues to develop in “On Morality,” as she argues that the misinterpretation of morality led to the gradual abandonment of traditional, accepted values, and developed into the self-deception of society. Childhood is the time of development of ideas and values, but Didion found that parents began to neglect teaching their children the traditional values of society, resulting in the center not holding. She states: “for better or worse, we are what we learned as children” (158). Her childhood was, as she explains, outlined by the traditional values of the WWI and WWII societies, before the social movement of the 1960s began. She was taught the basis of morality through graphic stories of those who had failed in their primary loyalties to each other: Some might say that the Jayhawkers were killed by the desert summer, and the Donner Party by the mountain winter, by circumstances beyond their control; we were taught instead that they had somewhere abdicated their responsibilities, some-how breached their primary loyalties, or they would not have found themselves helpless in the mountain winter or the desert summer, would not have given way to acrimony, would not have deserted one another, would not have failed. (158-159) The parents of Didion’s childhood related the understanding of morality to cautionary tales, prompting their children to recognize the mistake made and therefore prevent them from repeating that mistake in their own lives. She proposes that the moral and ethical dimensions of events were best understood before the 1960s through narrative and experience. “They still suggest,” she explains, “the only kind of morality that seems to me to have any but the most potentially mendacious meaning” (159). Yet these stories stopped being told sometime after WWII, and people never learned the meaning of morality at the time when they were most impressionable: during childhood. In “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” Didion suggests: “at some point between 1945 and 1967 we had somehow neglected to tell these children the rules of the game we happened to be playing” (123). Parents stopped believing in accepted ideas, and their children were never told these cautionary tales that would develop an understanding of concepts such as morality, leading to the growing misinterpretation of established values. As the traditional definition of morality was abandoned by youths during the 1960s, the word became consistently used, as Didion explains, incorrectly, providing further evidence that traditional societal values were being lost. Morality is based, according to Didion, most legitimately on the promises and loyalties that we, as people, agree upon. To strengthen this idea, Didion follows the roots instilled in her upbringing, giving an example through story. She recounts an instance in which an apparently intoxicated young boy wrecked his car, killing himself and injuring his girlfriend. One man guarded the boy’s body while his wife took the girl to the hospital, out of moral duty, and Didion comments: One of the promises we make to one another is that we will try to retrieve our casualties, try not to abandon our dead to the coyotes. If we have been taught to keep our promises—if, in the simplest terms, our upbringing is good enough—we stay with the body, or have bad dreams. (158) Didion approves of this morality, as in the instance it is the protection of our own race, the promise that we would not abandon each other to the coyotes. It is generally an accepted belief and value that we must stand up for each other in the face of great danger or peril, the idea that no man should be left behind. Beginning shortly after WWII, however, the growing consensus was that morality referred to ideas of right and wrong, instead of this “primitive” reference to human survival, the “social code.” This misinterpretation of morality led to society’s self-deception as Didion explains: “‘I followed my own conscience.’ ‘I did what I thought was right.’ How many madmen have said it and meant it?” (161). This “right and wrong” understanding of morality serves little purpose other than to supply falseexplanation to one’s actions. Didion expresses her disdain for this belief by comparing those who follow it to “madmen” – she suggests that society’s acceptance of this false notion of morality lowers us to just one step away from madmen. Not only is this new idea of morality incorrect, but it is completely paradoxical. Right and wrong, as Didion claims, are impossible to know beyond the general social code among humans. The misinterpretation of morality in this light, this self-deception and confusion of personal actions with moral obligation, reflects the loss of traditional values in society, and reflects her claim that “the center was not holding.” Shortly after WWII, “mass hysteria” began being heard throughout the nation, as the direct result of children’s misinterpretation of morality. Parents lost confidence in traditional values and ideas, and stopped teaching their children the correct “rules” of their society. This was definite evidence that societal values were losing their significance, and as youths left these ideas behind they developed their own, improper definitions for values. Morality became less of a widely accepted ethical belief, and more of a personal conception of right and wrong, the “ideal good.” People began to associate the word incorrectly with their conscience, the reason behind what they were doing. Yet society was deceiving itself, hinting to this “hysteria” being heard throughout the land. As Didion explains: When we start deceiving ourselves into thinking not that we want something or need something, not that it is a pragmatic necessity for us to have it, but it is a moral imperative that we have it, then is when we join the fashionable madmen, and then is when the thin whine of hysteria is heard in the land, and then is when we are in bad trouble. And I suspect we are already there. (163) It is dangerous to society to equate wants and needs with the moral imperative, and it puts us in the same position as madmen. We cannot claim the primacy of personal conscience, because we have no way of truly knowing what is “right” and “wrong” beyond the social code among humans. These developments, these false definitions of morality, reflect change in societal values and support Didion’s claim that “the center was not holding.” As she suggests, society had degraded to the point of hysteria and self-deception due to the abandonment of traditional values.