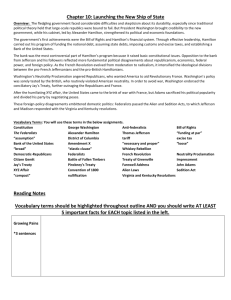

Ch 10 The New Ship of State

advertisement

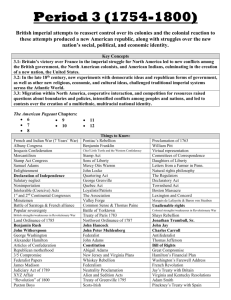

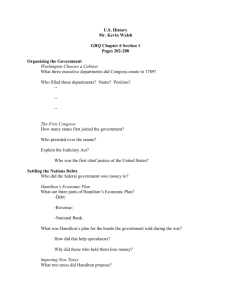

Chapter 10 Launching the New Ship of State, 1789–1800 I. Growing Pains • United States was growing rapidly: – Population doubled every twenty-five years – First official census, 1790, recorded 4 million – Cities blossomed proportionately: • Philadelphia—42,000 New York—33,000 Boston— 18,000 Charleston—16,000 Baltimore—13,000. – America’s population was still 90% rural: • All but 5% lived east of the Appalachian Mountains • Overflow concentrated in Ky., Tenn., Ohio. I. Growing Pains (cont.) • People in the west were particularly restive and dubiously loyal: – The mouth of the Mississippi lay in Spanish hands – Many observers wondered whether the emerging United States would ever grow to maturity. II. Washington for President • George Washington was unanimously drafted as president by the Electoral College in 1789: – The only presidential nominee ever to be honored by unanimity – He was the only one who did not in some way angle for this exalted office – He commanded by strength of character rather than the arts of the politician. II. Washington for President (cont.) – Washington’s long journey from Mount Vernon to New York City was a triumphal procession – Took the oath of office on April 30, 1789, on a crowded balcony overlooking Wall Street – Washington put his stamp on the new government by establishing the cabinet – The Constitution did not mention a cabinet (see Table 10.1) it merely provided that the president may require written opinions (see Art. II, Sec. II, para. 1 in the Appendix). II. Washington for President (cont.) • At first only three full-fledged department heads served under the president: – Secretary of State—Thomas Jefferson – Secretary of the Treasury—Alexander Hamilton – Secretary of War—Henry Knox. p181 III. The Bill of Rights • Failure of the Constitution to provide: – Guarantees of individual rights such as freedom of religion and trial by jury • Some ratified the Constitution on the understanding they would soon be included • Drawing up a bill of rights headed the list of imperatives facing the new government. III. The Bill of Rights (cont.) • Amendments could be proposed in two ways: • By a new constitutional convention requested by twothirds of the states • Or by a two-third vote of both houses of Congress • James Madison determined to draft the amendments himself he then guided them through Congress – The Bill of Rights, adopted by the necessary states in 1791, safeguard some of the most precious American principles. III. The Bill of Rights (cont.) • Among these: protections for freedom of religion, speech, and the press • Right to bear arms • Right to be tried by a jury • Right to assemble and petition the government for a redress of grievances • The Bill of Rights also prohibited: – Cruel and unusual punishment – Arbitrary government seizure of private property III. The Bill of Rights (cont.) • Madison inserted the Ninth Amendment: – It declares that specifying certain rights “shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people” • Reassurance to the states’ righters • He also included the Tenth Amendment: – Which reserves all rights not explicitly delegated or prohibited by the federal Constitution “to the States respectively, or to the people.” III. The Bill of Rights (cont.) • Thus Madison’s amendments swung the federalist pendulum back in an antifederalist direction (See Amendments I-X.) • The Judiciary Act of 1789: – Organized the Supreme Court with a chief justice and five associates, federal district and circuit courts, established the office of attorney general. – John Jay became the first chief justice. Table 10-1 p182 IV. Hamilton Revives the Corpse of Public Credit • Hamilton’s role in the new government: – Worked to correct the economic vexations of the Articles of Confederation: • Planned to shape the fiscal policies of the administration in favor of the wealthier groups • First to bolster the national credit • Funding at par: – Urged Congress to “fund” the entire national debt “at par” – And urged Congress to assume completely the debts incurred by the states during the recent war. IV. Hamilton Revives the Corpse of Public Credit (cont.) • Funding at par meant that the federal government would pay off its debts at face value, plus accumulated interest—a total sum of $54 million • Because people believed this was impossible for the government, bonds depreciated to ten or fifteen cents on the dollar. • Congress passed Hamilton’s measure in 1790. – Hamilton urged Congress to assume the debts of the states, totaling some $21.5 million: • Assumption: the state debts could be regarded as a proper national obligation IV. Hamilton Revives the Corpse of Public Credit (cont.) • He believed that assumption would chain the states more tightly to the “federal chariot” • It would shift the attachment of wealthy creditors from the states to the federal government • States burdened with heavy debts, like Massachusetts were delighted by Hamilton’s proposal • States with small debts, like Virginia, were less charmed • While Virginia did not want the state debts assumed, they did want the forthcoming federal district—now District of Columbia, located on the Potomac River. p183 V. Customs Duties and Excise Taxes • The new ship of state was dangerously overloaded: – The national debt was $75 million – Hamilton, “Father of the National Debt,” was not greatly worried – Believed within limits, a national debt was a “national blessing” – Wanted to make debt an asset for vitalizing the financial system (see Figure 10.1). V. Customs Duties and Excise Taxes (cont.) • Money was to come from customs duties: – Tariff revenues from a vigorous foreign trade – The first tariff law imposed 8% on the value of dutiable imports, passed in 1789 • Revenue was the main goal • Was also designed to erect a low protective wall around infant industries • Hamilton wanted to see the Industrial Revolution come to America, thus urged more protection for the well-to-do manufacturing groups V. Customs Duties and Excise Taxes (cont.) • Congress only voted two slight increases in the tariff during Washington's presidency • Hamilton sought additional internal revenue: – In 1791 secured an excise tax on a few domestic items, notably whiskey • New levy of 7 cents a gallon borne by the distillers who lived in the backcountry • Whiskey flowed so freely on the frontier in the form of distilled liquor that it was used for money. Figure 10-1 p184 VI. Hamilton Battles Jefferson for a Bank • Hamilton’s capstone: proposed a bank of the United States: – Took his model from the Bank of England – Proposed a powerful private institution, with the government the stockholder and where the federal Treasury would deposit its surplus monies – The federal funds would stimulate business by remaining in circulation VI. Hamilton Battles Jefferson for a Bank (cont.) – The bank would print urgently needed money, providing a sound and stable national currency • Jefferson was vehemently against the bank • He insisted that there was no specific authorization in the Constitution • He believed that all powers not specifically granted to the central government were reserved to the states (see Amendment X) • He concluded that the states, not Congress, had the power to charter banks. VI. Hamilton Battles Jefferson for a Bank (cont.) • Hamilton, at Washington’s request, prepared a brilliantly reasoned reply to Jefferson’s arguments • He believed the Constitution did not forbid it • Jefferson believed that what it did not permit it forbade • Hamilton invoked the clause of the Constitution that stipulates that Congress may pass any laws “necessary and proper” to carry out the powers vested in the various government agencies (see Art. I, Sec. VIII, para. 18) • Congress was empowered to collect taxes VI. Hamilton Battles Jefferson for a Bank (cont.) • Congress was empowered to regulate trade • Therefore, according to Hamilton a national bank was necessary—implied powers and “loose” interpretation of the Constitution • Hamilton ‘s financial views prevailed • Washington signed the bank measure into law • The most support for the bank came from the commercial and financial centers of the North • The strongest opposition arose from the agricultural South. VI. Hamilton Battles Jefferson for a Bank (cont.) • The Bank of the United States was created by Congress in 1791: – Chartered for twenty years – Located in Philadelphia – It was to have a capital of $10 million, 1/5 owned by the federal government – Stocks were thrown open to public sale. p185 VII. Mutinous Moonshiners in Pennsylvania • The Whiskey Rebellion: – Flared up in southwestern Pennsylvania – Big challenge for the new national government – Hamilton’s high excise tax hurt – Defiant distillers cried “Liberty and No Excise” – Washington summoned the militias – When the troops reached western Pennsylvania, they found an insurrection – Two convicted culprits were pardoned. VIII. The Emergence of Political Parties • All Hamilton’s schemes encroached sharply upon states’ rights: – Organized opposition began to build – Now there was a full-blown bitter political rivalry • National political parties: • Unknown in America when Washington took his inaugural oath • The Founders had not envisioned the existence of permanent political parties VIII. The Emergence of Political Parties (cont.) • The two-party system has existed in the United States since that time (see Table 10.2): – Their competition for power proved to be the indispensable ingredients of a sound democracy – The party out of power plays the invaluable role of the balance wheel, ensuring that politics never drifts too far. Table 10-2 p186 p187 IX. The Impact of the French Revolution • Now there were the two major parties: • Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans • Hamiltonian Federalists – With Washington’s second term, foreign-policy issues brought the differences between the parties to a fever pitch – The first act of the French Revolution, 1789: • Twenty-six years later Europe would come to a peace of exhaustion. IX. The Impact of the French Revolution (cont.) • Few non-American events have left a deeper scar on American political and social life: • Early stages—surprisingly peaceful • Attempted to impose constitutional restrictions on Louis XVI • 1792 France declared war on Austria • News later reached America that France had proclaimed itself a republic • Americans were enthusiastic. IX. The Impact of the French Revolution (cont.) • The guillotine was set up, the king was beheaded in 1793 • The church was attacked • The head-rolling Reign of Terror had begun • The earlier battles had not hurt America directly, but not until Britain was caught into the revolution did the revolution spread to the New World. • Every major European war, beginning in 1688, involved a watery duel for control of the Atlantic Ocean (See Table 6.2, p. 103). p188 p189 X. Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation • French-American alliance of 1778: – Bound the United States to help the French defend their West Indies – Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans favoring honoring the alliance – America owed France its freedom, and now was the time to pay the debt of gratitude – Washington was not swayed by the clamor of the crowd. X. Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation (cont.) • Washington: • Believed that war had to be avoided at all costs • The strategy of playing for time while the birthrate fought America’s battles was a cardinal policy of the Foundling Fathers • Hamilton and Jefferson were in agreement. – In 1793 Washington issued his Neutrality Proclamation shortly before war broke out between England and France. X. Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation (cont.) • Neutrality Proclamation: • Proclaimed the government’s official neutrality in the widening conflict • Sternly warned American citizens to be impartial toward both armed camps – America’s first formal declaration proved to be a major prop of spreading isolationist tradition • It proved to be enormously controversial • The pro-French Jeffersonians were enraged and the British Federalists were heartened. X. Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation (cont.) • Debate intensified: – Citizen Edmond Genet, representative of the French Republic, landed at Charleston, S. Car. • Was swept away by his enthusiastic reception by the Jeffersonian Republicans • He came to believe that the Neutrality Proclamation did not reflect the American people’s wishes • Thus embarking on non-neutral activity not authorized by the French alliance • Washington demanded Genet’s withdrawal. X. Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation (cont.) • Neutrality Proclamation: – Illustrates the truism that self-interest is the basic cement of alliances – In 1778 both France and America stood to gain – In 1793 only France did – Technically , the Americans did not flout their obligation because France never officially called on them to honor it – America was more useful to France. Map 10-1 p191 XI. Embroilments with Britain • President Washington’s policy of neutrality was sorely tried by the British: • For ten years they maintained a chain of northern frontier posts on U.S. soil in defiance of the peace treaty of 1783 (see Map 10.1) • London was reluctant to abandon her lucrative fur trade • London also hoped to build an Indian buffer state • They openly sold firearms and firewater to the Indians of the Miami Confederacy XI. Embroilments with Britain (cont.) • Battle of Fallen Timbers, 1794: – General “Mad Anthony” Wayne routed the Miamis – British refused to shelter the Indians fleeing the battle; the Indians offered Wayne the peace pipe – In the Treaty of Greenville, August 1795, they gave up vast tracts of the Old Northwest – In exchange they received $20,000 and an annual annuity of $9,000 XI. Embroilments with British (cont.) – The right to hunt the lands they had ceded – They hoped for recognition of their sovereign status – The Indians felt it put some limits on the ability of the United States to decide the fate of Indian peoples. XI. Embroilments with the British (cont.) • The British seized 300 American merchant ships, impressed scores of seamen into British service and threw hundreds into foul dungeons. • Impressment incensed patriotic Americans • War with the world’s mightiest commercial empire would pierce the heart of the Hamiltonian financial system. p192 XII. Jay’s Treaty and Washington’s Farewell • Jay’s Treaty: – Washington decided to send Chief Justice John Jay to London in 1794 • In London, Jay routinely kissed the queen’s hand, must to the dismay of the Jeffersonians • Jay entered the negotiations with weakness, which was further sabotaged by Hamilton • Jay won few concessions XII. Jay’s Treaty and Washington’s Farewell (cont.) • British concessions: – They promised to evacuate the chain of posts on U.S. soil – Consented to pay damages for the seizure of American ships – But the British stopped short of pledging: • Anything about future maritime seizures and impressments • Or about supplying arms to the Indians. XII. Jay’s Treaty and Washington’s Farewell (cont.) • Jay’s unpopular pact: • Vitalized the newborn Democratic-Republican party • It was seen as a betrayal of the Jeffersonian South • Even Washington’s huge popularity was compromised by the controversy over the treaty. – Other consequences: • Fearing an Anglo-American alliance, Spain moved to strike a deal with the United States in the Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795. XII. Jay’s Treaty and Washington’s Farewell (cont.) • Pinckney’s Treaty: • Granted the Americans virtually everything they wanted from Spain: – Including free navigation of the Mississippi – The right of deposit (warehouse rights) at New Orleans – The large disputed territory of western Florida (See Map 9.3 on page 167.) • Washington decided to retire – Exhausted from diplomatic and partisan battles, he decided against future terms. XII. Jay’s Treaty and Washington’s Farewell (cont.) – His choice contributed powerfully to establishing a two-term tradition for American presidents. • His Farewell Address to the nation in 1796: – It was never delivered orally, printed only in the newspapers – He strongly advised the avoidance of “permanent alliances” • But only favored “temporary alliances” for “extraordinary emergencies” XII. Jay’s Treaty and Washington’s Farewell (cont.) • Washington’s contributions: • • • • The federal government was solidly established The west was expanding The merchant marine was plowing the seas He kept the nation out of both overseas entanglement and foreign wars – When Washington left office in 1797, he was showered with the brickbats of partisan abuse, quite in contrast with the bouquets that had greeted his arrival. XIII. John Adams Becomes President • John Adams, with the support of New England, won with the narrow margin of 71 to 68 votes in the Electoral College: – Jefferson, as runner up, became vice-president – Adams was a man of stern principles, who did his duty with stubborn devotion – He was a tactless and prickly intellectual aristocrat – Had no appeal to the masses – He was regarded with “respectful irritation.” XIII. John Adams Becomes President (cont.) • He had other handicaps: – He had stepped into Washington’s shoes, which no successor could hope to fill – He was hated by Hamilton – Most ominous of all, Adams inherited a violent quarrel with France—a quarrel whose gunpowder lacked only a spark. p193 XIV. Unofficial Fighting with France • The French were infuriated by Jay’s Treaty: • Condemned it as the initial step toward an alliance with Britain, their perpetual foe • Assailed it as a flagrant violation of the FrancoAmerican Treaty of 1778 • French warships, in retaliation, began to seize defenseless American merchant vessels, three hundred by mid-1797 • The Paris regime refused to receive America’s newly appointed envoy and even threatened to arrest him. XIV. Unofficial Fighting with France (cont.) • Adams tried to reach an agreement with the French: • Appointed a diplomatic commission of three men, including John Marshall, the future chief justice • Adam’s envoy reached Paris in 1797 where they hoped to meet with Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, the crafty French foreign minister • They were secretly approached by three gobetweens, later referred to as X, Y, and Z • They demanded a loan of 32 million florins. XIV. Unofficial Fighting with France (cont.) • Plus a bribe of $250,000 for the privilege of merely talking with Talleyrand • Terms were intolerable and negotiations quickly broke down • John Marshall, on reaching New York in 1798, was hailed as a conquering hero for his steadfastness. • The XYZ Affair sent a wave of hysteria sweeping through the United States. – The slogan of the hour “Millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute.” XIV. Unofficial Fighting with France (cont.) • War preparations: • Pushed along at a feverish pace, despite considerable Jeffersonian opposition in Congress • The Navy Department was created; the three-ship navy was expanded • The United States Marine Corps was reestablished • A new army of 10,000 men was authorized (but not fully raised) XIV. Unofficial Fighting with France (cont.) • War itself: • War was confined to the sea, mainly West Indies • 2 1/5 years of undeclared hostilities (1798-1800) • American privateers and men-of-war captured over 80 armed French vessels • Several hundred Yankee merchant ships were lost to the enemy – Only a slight push, it seemed, might plunge both nations into a full-dress war. p194 p195 XV. Adams Puts Patriotism Above Party • Embattled France wanted no war: • Talleyrand realized there was no use in fighting the United States • The British were driven closer to their wayward cousins • Talleyrand let it be known that if the Americans would send a new minister, he would be received with proper respect • This brought to Adams a degree of personal acclaim that he had never known before—and would never know again. XV. Adams Puts Patriotism Above Party (cont.) – Adam exploded a bombshell when in 1799 he submitted to the Senate the name of a new minister to France – American envoys found things better when they reached Paris early in 1800 – The Corsican Napoleon Bonaparte had recently seized dictatorial power – The Convention of 1800 treaty was signed in Paris. XV. Adams Puts Patriotism Above Party (cont.) • The Convention of 1800: • France agreed to annul the 22-year-old marriage of (in)convenience • As a kind of alimony the United States agreed to pay the damage claims of American shippers • John Adams deserves immense credit for his belated push for peace – He smoothed the path for the peaceful purchase of Louisiana three years later – His suggestion for his tombstone: “Here lies John Adams, who took upon himself the responsibility of peace with France in the year 1800.” XVI. The Federalist Witch Hunt • Federalist actions to muffle the Jeffersonian foes: • First, aimed at pro-Jeffersonian “aliens” – Raised the residence requirement from 5 years to 14 – This law violated traditional American policy of open-door hospitality and speedy assimilation • Second, Alien Laws— – President could deport dangerous foreigners in time of peace and defensible as a war measure – This was an arbitrary grant of executive power contrary to American tradition/Constitution. Never enforced. XVI. The Federalist Witch Hunt (cont.) • Third, Sedition Act—slap at two priceless freedoms guaranteed in the Constitution by the Bill of Rights: – Freedom of speech and freedom of the press (First Amendment) – This law provided that anyone who impeded the policies of the government, or falsely defamed its officials, would be liable to a heavy fine and imprisonment – Federalists believe it was justified • Many outspoken Jeffersonian editors were indicted under the Sedition Act and ten were brought to trial. • The Sedition Act seemed to be in direct conflict with the Constitution. p197 XVII. The Virginia (Madison) and Kentucky (Jefferson) Resolutions – Jefferson secretly penned a series of resolutions: • Approved by the Kentucky legislature in 1798, 1799 • Madison drafted a similar but less extreme statement adopted by the Virginia legislature in 1798 • Both stressed the compacts theory— – A theory popular among English political philosophers – This concept meant that the thirteen sovereign states, in creating the federal government, had entered into a “compact,” or contract, regarding its jurisdiction – The nation was consequently the agent or creation of the states. XVII. The Virginia (Madison) and Kentucky (Jefferson) Resolutions – The individual states were the final judges of whether their agent had broken the “compact” by overstepping the authority originally granted – Jefferson’s Kentucky resolutions concluded that the federal regime had exceeded its constitutional powers and that with regard to the Alien and Sedition Acts, “nullification” —a refusal to accept them—was the “rightful remedy.” • No other state legislatures fell into line: – The Federalist states added ringing condemnations – They argued that the people, not the states, had made the original compact, therefore it was up to the Supreme Court—not the states—to nullify unconstitutional legislation passed by Congress. XVII. The Virginia (Madison) and Kentucky (Jefferson) Resolutions • The Virginia and Kentucky resolutions: • Brilliant formulation of the extreme states’ rights view regarding the union • More sweeping in their implications than their authors had intended • Later used by southerners to support nullification— ultimately secession • Neither Jefferson nor Madison had any intention of breaking the union; they wanted to preserve it. XVIII. Federalists Versus DemocraticRepublicans – As the presidential contest of 1800 approached: • Federalists and Democratic-Republicans were sharply etched (see Table 10.3) • Conflicts over domestic politics and foreign policy undermined the unity of the Revolutionary era • Could the fragile and battered American ship of state founder on the rocks of controversy? • Why would the United States expect to enjoy a happier fate? Table 10-3 p198 p199 p201