Rise of the National Game

advertisement

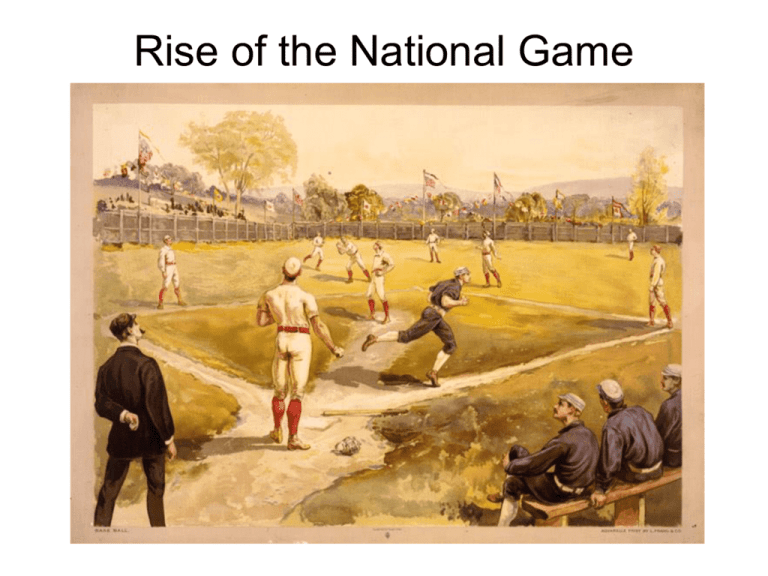

Rise of the National Game Baseball evolved by three main stages 1. 2. 3. Simple, informal folk game played mostly by boys. Contrary to myth propagated by organized baseball, Abner Doubleday did not invent baseball. Club-based fraternal game. In the 1840s and 1850s young men in several large cities formalized the bat and ball games by organizing clubs and adopting written rules; they played for personal pleasure and not for spectators Formation of the National League in 1876 signalled the full arrival of baseball as a business enterprise and a commercial, spectator-centered sport Children across America played different versions of bat and ball games since colonial times These bat and ball games were similar to the English game of rounders Abner Doubleday (1819-1893) was a United States Army officer who fired the first shot in the defense of Fort Sumter. In 1907, the National League concluded that that "the first scheme for playing baseball, according to the best evidence obtainable to date, was devised by Abner Doubleday at Cooperstown, New York, in 1839.” In truth, Doubleday never made such a claim, and there is no evidence to support it. In the 1840s, assorted “gentlemen” (clerks, store keepers, professional men, brokers) began playing town ball. Wall Street, 1867 In 1842, they gathered regularly at a vacant lot at 27th Street and 4th Avenue in Manhattan Lower Manhattan, 1847 2nd Avenue, looking north from 42nd Street One of the baseball players was Alexander Cartwright, a bank clerk and volunteer firefighter with the Knickerbocker Engine Company No. 12. When the vacant lot became unavailable, Cartwright urged the men to find a permanent playing site and form a club During this time, much of the land in Hoboken, New Jersey – just across the Hudson River from Manhattan was owned by the wealthy and politically-connected John Cox Stevens. Steven wished to parcel out his property for sale to New York residents. In order to attract visitors, Stevens sectioned off a riverfront parcel, dubbed Elysian Fields, as a country-like retreat for the masses. Elysian Fields The idyllic setting offered a weekend and evening getaway from hectic, unhealthy city life. During the park’s heyday, visitors were treated to parades, fireworks, amusement rides, community events, ice skating, religious retreats, landscaped gardens, a promenade, cricket playing, variety of food and drink, a restorative drinking spa, duels, hot air balloon displays, concessions of many sorts, cattle auctions, bowling, bands, concerts, plays, optical displays, artisans, dances, dancing, political meetings and rallies, an array of performers, a locomotive ride, yachting and rowing races, vast picnic areas, a deer park, horse racing, fishing, wrestling and boxing matches, ploughing (lumberjack) contests, singing, a “buffalo” hunt, fascinating oddities, and ethnic celebrations. Stevens agreed to rent out an area of Elysian Fields to the New York base ball players for $75 per year. On September 26, 1845, Cartwright organized a formal ball club in order to collect fees to cover the rent. The club was called the Knickerbockers, in honor of his fire company. On behalf of the Knickerbockers, Cartwright created formal rules for playing the game and gentlemanly behavior. The Knickerbockers played on weekends and practiced twice a week on their new grounds. Knickerbocker Rules • Infield must be diamond-shaped with bases at each of the four corners; bases were located 90 feet from one another • Tagging a runner replaced “soaking” or “plugging,” a painful feature of rounders • At-bat team limited to three outs • Fielders could obtain outs by catching the ball on the first bounce or in the air, throwing to first base ahead of the runner, or tagging the runner between bases Other base ball clubs soon organized. They usually consisted of enough members to comprise at least two teams. The clubs initially played intra-club games, but interclub games were eventually played. Like other voluntary associations, the Knickerbockers drew up bylaws, elected officers, and held regular meetings. In the earliest days of the sport, one became a club member by invitation only. On June 19, 1846, the Knickerbockers' second team lost 23-1 to the New York Base Ball Club in the first official, prearranged match between two clubs. A base ball game at Elysian Fields, 1859. In a post-game ceremony, the winning team received the game ball as a prize, and the home club usually provided the visitors with gala dinners In 1858, the early clubs formed the National Association of Base Ball Players, which assumed responsibility for rulemaking and attempted to preserve the fraternal character of the sport. This photograph, taken by Brooklyn photographer Charles H. Williamson, depicts the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club and the Excelsior Base Ball Club in one of the earliest known team photos and perhaps the first image on a baseball field. It was taken on September 3, 1859, at Elysian Fields, Hoboken, New Jersey. Grand Match for the Championship at the Elysian Fields, Hoboken, New Jersey,1865. This Currier and Ives painting is often misidentified as portraying the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York in action in the 1840s. However, the portrayed clubs are the Brooklyn Atlantics, at the bat, and the New York Mutuals in the field; the date of the match is August 3, 1865. 1865 Brooklyn Atlantics, 1865 When the Civil War erupted in 1861, there were more than 600 clubs in more than 100 cities. The war encouraged the introduction of base ball to hamlets across the nation. Gettysburg, 1864 The “national game” • 1850s was the decade that spawned the nativist, anti-Catholic Know Nothing political movement, as well as the bitter sectional rivalries that culminated in the Civil War • Yearnings for national unity spilled over into the sports arena • Many of the first baseball clubs openly avowed their nationalism with names such as Young America, Columbia, Union, Eagle, American, National and Liberty In 1857, Porter’s Spirit declared that Americans should have “a game that could be termed a Native American Sport.” Baseball, its supporters agreed, filled the need, for it had evolved as a distinctive American sport and embodied the fastpace nature of American life The press helped to promote baseball. Porter’s Spirit of the Times and the New York Clipper not only reported results but also lent direct aid to young men interested in forming clubs. No single journalist gave the sport greater assistance than Henry Chadwick, who edited baseball’s annual guidebook (circulation of 65,000) and invented the box score and batting averages, which enhanced the appeal of the sport Baseball as a Commercial Enterprise • By 1860, charging admission to games had become commonplace • Gate receipts used to pay star players • Fraternal bonds weakened; the post-game rituals of awarding the game ball to the winning team and hosting a dinner for the visitors had disappeared from the sport • Fans cheered for their heroes, heckled umpires and opposing players, and sometimes rioted 1869 Forst City Club, Cleveland OH The formation of the Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1869 as the first avowedly all-professional team ended the pretense of baseball’s pristine amateurism Led by Harry Wright, the Red Stockings recruited five eastern stars and swept through the 1869 season of 58 games without a loss and only one tie. Over 23,000 fans watched their six-game series in New York. In September, the club crossed the US on the newly completed transcontinental railroad to play a series of games in California NAPBBP, 1871-1875 • The success of the Red Stockings encouraged the formation of the first all-professional league, the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players • Team entry fee of $10 • Many teams in smaller cities joined but quickly dropped out • Teams scheduled their own games • Players were free to move from one club to another at the end of each season • Some players enjoyed salaries two or three times higher than the ordinary workingmen of the era National League poster, 1874 Harry Wright’s Boston Red Sox dominated the new league (Wright brought most of his Cincinnati team with him to Boston). After losing the pennant to Philadelphia in 1871, the Red Sox then won the next four consecutive championships. In 1876 a few men, led by coal baron William A. Hulbert – president of the Chicago club – conspired to overthrow the national association and found a new professional league that would be profitable to investors. After secretly obtaining the support of the western clubs that resented the eastern domination of the NAPBBP, Hulbert called a meeting with representatives of five eastern clubs. After reviewing the weaknesses of the association, he proposed The National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs. The National League • Charter members included Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Louisville, Hartford, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and New York • Gave owners complete control of the management, regulations, and the resolution of disputes • To appeal to Victorian sensibilities, it forbade Sunday games and betting in ball parks The National League • Pioneered a business structure that would become standard for all 20th century professional team sports • Forbid negotiations with players from another team while season was in progress • In 1879, the owners secretly agreed to “reserve” five players • Prohibited the planting of more than one franchise in each city The National League • Established an entry monopoly • Two blackballs by existing franchises barred new applicants from the league • In order for an aspiring baseball owner to obtain a league franchise, he had to win the votes of the owners of existing clubs, purchase an existing club, or … form a competing major league For its first six years, Hulbert offered the National League strong – albeit sometimes questionable – leadership. His highhanded and dictatorial methods improved the image of professional baseball, but when he died the league directors made certain that none of his successors obtained similar powers. Hulbert’s decisions • Hulbert mandated the charging of a uniform admission price of 50 cents for all games (when daily wages were one to three dollars) • In 1876 (first year of the league), he expelled New York and Philadelphia for failing to make their final road tours • In 1877, he expelled four Louisville players for taking bribes from gamblers • In 1880, he expelled Cincinnati for its insistence on selling beer at its park and renting its park out on Sundays The expulsion of Cincinnati led to a direct challenge to the National League American Association of Base Ball Clubs • In 1881, Cincinnati called together delegates from cities that had been excluded from the league • Charter franchises were located in Baltimore, Cincinnati, Louisville, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and St. Louis • Dubbed the “Beer Ball League” since four of the six directors owned breweries • Charged 25 cents admission, sold liquor at games, and allowed Sunday games • Invited National League players to join National Agreement • The success of the American Association cause the leaderless National League to call for a surrender in 1882 (Hulbert had died in April, 1882) • The presidents of the two leagues, plus the head of the Northwestern League (MI, OH, IL) signed an agreement • At the heart of the agreement was the mutual recognition of reserved players and the establishment of exclusive territorial rights 1880s Baseball • Booming US economy resulted in increased attendance at baseball games • Informal post-season series between the two leagues also increased interest • St. Louis Browns won four American Association pennants and two “World Series” from National League opponents • Clubs made profits, but competition for player talent drove up salaries • Clubs in both leagues violated the spirit of the 1882 National Agreement 1889 St. Louis Browns, managed by Charles Comiskey, who would later own the Chicago White Sox Demise of the American Association • American Association club owners, especially Brooklyn and St. Louis, fought for management of the league • When the American Association chose a puppet of the St. Louis Browns as president in 1890, Brooklyn and Cincinnati resigned and joined the National League • The National League ignored the National Agreement, indicating that it was prepared to resume an all-out war with the Association • Attendance at Association games dropped drastically • At the end of 1891, the Association surrendered • The National League then absorbed four Association clubs, making it a twelve-member league, and bought out the other four clubs The Players’ Revolt • Owners devised ingenious methods of keeping players’ salaries at a minimum • From its founding in 1876, the National League employed the dreaded “blacklist” – once a player had been dismissed by a club or the league, no other club could negotiate with him • In the 1880s, club owners agreed on uniform salary limits • The backbone of owner control was the reserve clause in player contracts The Reserve Clause • The club that first signed a player had a lifetime option on that player’s services • During negotiations, a player had only two options: refuse to play until he received his requested salary, or quit playing the game • The reserve clause also made it possible to buy and sell players • These measures triggered a players’ revolt in the mid-1880s John Montgomery Ward, a player and a lawyer, founded the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players in 1885. When the league set a $2500 ceiling on all players in 1887, Ward presented the league with an ultimatum: abandon the salary limit and stop selling players, or a new league would be formed in 1890. The league ignored his threats. Ward formed the Players’ National League of Professional Base Ball in 1890. The players challenged the National League directly by invading seven of its cities with new franchises and lured most of its players away from the senior loop. The Players’ League obtained enough financial backing to be initially successful. In a novel departure from the traditions of private enterprise, the players and investors assumed joint management of the new enterprise. The National League appointed Albert Spalding to suppress the player uprising. He denounced the players as “hot-headed anarchists” who were typical of “revolutionary movements.” The courts held that the contracts containing reserve clauses lacked equity, thereby permitting the players to jump to the new circuit with impunity. The Players’ League • Only survived one season • Competing in the same cities on the same days, both leagues gave away free tickets • The richer owners in the National League could withstand the financial sacrifices more easily than could the Players’ League investors • Some of the investors withdrew support and some players went back to the National League • After one season, the experiment in cooperative-capitalistic baseball ended in failure