THINK ABOUT MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA

advertisement

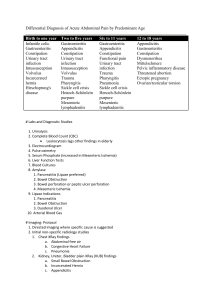

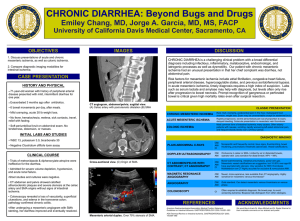

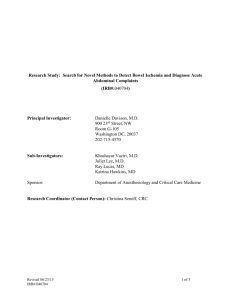

SEVERE ABDOMINAL PAIN OUT OF PROPORTION TO FINDINGS ON EXAMINATION … THINK ABOUT MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA Sudden reduction in arterial perfusion of the small bowel results in immediate central abdominal pain Progressive involvement of muscular layer Serosa Peritoneal signs Acute mesenteric ischemia Thrombotic Embolic Non-occlusive Thrombotic Due to an acute arterial thrombosis which occludes the orifice of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), resulting in massive ischemia of the entire small bowel plus the right colon Embolic Due to a shower of embolic material originating proximally – from the heart (AF, post MI, diseased valve) or aneurysmal or atherosclerotic aorta. Emboli lodge at the proximal SMA, below the entry of the middle colic artery, therefore the most proximal segment of the jejunum is spared. Emboli tend to fragment and re-emboli distally – producing a patchy type of ischemia Non-occlusive Low flow state – no documented thrombosis or emboli Low cardiac output (cardiogenic shock), reduced mesenteric flow (increased intra-abdominal pressure) or mesenteric vasoconstriction (administration of vasopressors) Usually develops in the setting of pre-existent critical illness Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis Can also produce small bowel ischemia Clinical features and management completely different from the above three The problem – in clinical practice mesenteric ischemia is usually recognized too late, after it has led to intestinal gangrene, sepsis and organ failure Even if the patient survives - development of short bowel syndrome Therefore – early diagnosis and treatment are crucial Clinical picture The early clinical picture is non-specific – severe abdominal pains, minimal abdominal findings Preceding symptoms – mesenteric angina (pain with meals, weight loss) History of IHD Source of emboli Low flow state in moribund patients due to underlying critical disease If peritonitis – usually signifies dead bowel Abdominal x-rays in the early course of the illness are normal. Later – adynamic ileus Laboratory tests – initially normal. As bowel ischemia progresses – leukocytosis, hyperamylasemia, lactic acidosis Therefore – high level of suspicion and active search for the diagnosis in the early phase to prevent bowel necrosis Abdominal CT-Angio Mesenteric Angiography Contraindicated in the presence of acute abdomen Mesenteric Angiography Invasive, takes time and requires experienced personnel – only if CT-Angio non diagnostic and there is still high probability of vascular event To rule out non-occlusive disease Advantage – can be therapeutic Occluded ostium of SMA – Thrombosis, immediate operation unless good collateral flow. The angio provides road map for reconstruction. In Emboli, the first few cm of SMA are patent Non-operative Treatment Only if no peritoneal signs, usually in emboli Selective infusion of thrombolytic agent, papaverine to relieve the associated mesenteric vasospasm Only cessation of abdominal symptoms and angiographic resolution can be regarded as a success In non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia – attempt to improve intestinal flow by restoring altered hemodynamics. Selective intra-arterial infusion of vasodilator. In emboli – long term anti-coagulation Operative Treatment Peritoneal signs Failure of non-operative regimen Two possibilities : Frank gangrene Ischemia, questionable viability Frank Gangrene Gangrene of the entire small bowel and right colon – signifies SMA thrombosis. Total resection + TPN for life not practical Shorter gangrene or multiple segments – emboli. Excision of all dead bowel and evaluation of the rest. Less than 1 meter of small bowel will require in half of patients TPN for life Questionable viability Possibility of embolectomy in emboli or vasculoar reconstruction – only if bowel questionably viable. Consider second-look operation if remaining questionable bowel too long and massive resection required Signs of viability – color, peristalsis, pulsation in mesenterium Anastomosis – selectively. Stable patient, fair nutritional status, remaining bowel unquestionably viable, no severe peritonitis. Anastomosis after massive resection – intractable diarrhea The main reason not to anastomose – the possibility that further ischemia may develop If anastomosis not safe – exteriorize both end of the bowel as endileostomy and mucous fistula for a later re-anastomosis Second-look Operation A planed re-operation – has to be decided during the first operation Allows to re-assess intestinal viability Allows to preserve the greatest possible length of viable intestine Has to be done after 24-48 hours to prevent SIRS Mesenteric Vein Thrombosis Occlusion of the venous outflow of the bowel. Rare, may be idiopathic or secondary to hypercoagulable state or sluggish portal flow (cirrhosis) Clinical presentation non-specific, may last several days until the intestine is compromised and peritoneal signs develop CT may be diagnostic – intra-peritoneal fluid, thickened segment of small bowel, thrombus in the SMV MVT - Treatment If no peritoneal signs – full anticoagulation – may result in spontaneous resolution and avoid surgery Failure to improve on heparin or peritoneal signs mandate an operation At operation – the involved segment of small bowel is thick, edematous, dark blue, arterial pulsation present, thrombosed veins. Resection of the involved segment, the same considerations as for arterial ischemia regarding anastomosis or second look. Postoperative anticoagulation to prevent thrombus progression