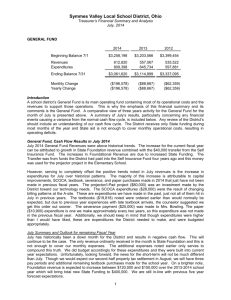

School Level Analysis across 15 Case Studies

advertisement

The Financial Management of Primary Schools: Case Studies from Turkey AYŞEN KÖSE and AYTUĞ ŞAŞMAZ Introduction In this paper, we investigate the details of the funding system of primary education in Turkey, and the consequences this mechanism generates especially at the school level. In order to better explain these consequences, we then turn to the policies of the government shaping this mechanism especially in the last decade. We find out that failed efforts towards decentralization, quasi-privatization in schools through parent-teacher associations due to insufficiency of public funds to cover current expenditures and the preference on the part of the central government to use public funds for cash transfers to individual students rather than increasing grants to schools led to the fact that public schools of primary education in Turkey have become weak institutions which cannot diversify and improve the education services they provide for their students. We hope that this paper can contribute to the studies of education finance by showing the links between the policies of remote central governments and the consequences of them in the level of schools in a clear and comprehensive way. The Constitution of Turkey states that primary education is compulsory for all girls and boys and free of charge in public schools. Since the Basic Education Reform in 1997, primary education begins at the age of 6 and lasts for eight years, covering also the lower secondary education in international terms (ISCED 2). While there are some exceptions especially in the rural area, most students are expected to attend the same school for eight years. Although there are private schools and special education schools, the overwhelming majority of students in primary education attend public schools. Thus, public primary schools are central to Turkish education system, hosting 65% of all students in formal K-12 education (see Table 1). 1 Table 1: Number of enrolled students and enrolment ratios in different levels of education in Turkey, 20102011 Number of enrolled students Net enrolment ratio Gross enrolment ratio 1,115,818 29.9% N/A Public primary schools (incl. regional boarding primary schools) 10,289,370 98.41% 107.58% Public schools for students with special needs 19,177 Private primary schools 267,294 69.33% 93.34% Pre-primary education Primary education Secondary education 3,970,397 Source: MoNE and Turkstat, Statistics of National Education, Formal Education, 2010-2011. The sources and mechanisms through which primary education is financed can be important in many ways. The most important questions may well be whether funds are sufficient to carry on and improve education services and also whether public and/or private funds are used to finance primary education. Another set of important questions relevant rather for those systems which are concerned about the quality of education are related to the division of roles and responsibilities between different levels of government in using the funds allocated to primary education. Turkish education system can be hypothesized to be in the middle: The system still copes with the issues of insufficiency of public funds as the number of students in the formal education system is high due to the young demographics of the country (public education spending is 4% of GDP as opposed to 5.7% in OECD countries) (ERI, 2011; OECD, 2010). At the same time, all stakeholders aim to implement policies to improve the quality of the system as the country ranked 32nd out of 34 OECD countries in the last cycle of the PISA in 2009 (OECD, 2011). The quality of education is a concern for both the government and different segments of the society, as the country aims to sustain its economic growth. In short, the structure through which Turkish primary education is financed can be hypothesized to be coping with twin challenges: First, public funds allocated to education may be frequently insufficient, and as a result, private spending on education may be quite high. Secondly, the funding system may not be structured in a way that it can enhance and support improvement and adaptability of education services provided by schools. Previous 2 work on financing of Turkish primary education overwhelmingly emphasized the former challenge. There are many studies claiming that public funds are insufficient to cover the expenses for primary education due to the young demographic structure, internal migration towards larger cities in the country (Kavak et al., 1997; Altuntaş, 2005) and limitations put by high amount of expenditures on investment (Koç, 2007). As a result, schools have to raise revenue using different ways. Studies suggest that there 22 to 60 different sorts of revenue generated by schools. Donations by parents, incomes generated through hiring out school facilities such as canteen and school garden (as parking lots) and fees charged for pre-primary classes make up the three most important sources of revenue (Kavak et al., 1997; Zoraloğlu et al., 2005; Yolcu and Kurul, 2009). Studies also suggest that the sources of revenue may be different for schools in different locations in terms of socio-economic status: While schools located in higher socio-economic status may diversify their sources of revenue as they can rent out school facilities better, those located in lower socio-economic status are more dependent on donations by parents (Özdemir, 2011). This study offers a more comprehensive picture. Thanks to its methodology which includes review of legislation, review of relevant expenditure data, interviews with bureaucrats from different public agencies in different levels and interviews with different stakeholders in 15 schools across Turkey, we consider both possibilities, namely the insufficiency of public funds and inadequacy of the mechanisms to use them. We find out that both are important, and explain the policies which are put into practice to overcome the insufficiency and also those that led to the inadequacy, and how they play out in the school level. We conclude by suggesting that, as one of the most rapidly growing countries in the world, Turkey should consider to restructure its funding system for primary education to be able to position schools as powerful institutions so that it can increase the quality of education. This study was enabled through a Project Cooperation Agreement signed between UNICEF Turkey Country Office and Education Reform Initiative (ERI), an education policy think-tank based in Istanbul. Funded jointly, but by a greater extent by UNICEF, two institutions are collaborating with the DG for Basic Education of the Ministry of National Education of Turkey (MoNE) to conduct research in three different areas. “Financial Management of Primary Education” is one of these studies. In each of these areas, research reports are prepared out of whose findings policy options and recommendations will be presented to 3 MoNE. Research reports and policy notes are soon to be published jointly by MoNE, UNICEF and ERI.1 Methodology This is a descriptive research aiming at explaining the current funding system of primary education in Turkey with its public and private sources. This section explains the methodology of the research including how the participants are selected and which methods are used to collect and analyze data. The study has been carried out using the multiple case study method, which is one of the qualitative research methods. In this study, the phenomenon examined at the micro (school) level is the process of raising and spending both monetary and in kind resources flowing from private contributors to public primary schools. The phenomenon in question is a complex process since it is not possible to clearly separate this phenomenon from the school itself and from the other dynamics that affect the school. Therefore, it needs to be thoroughly examined within its own real life framework. Since the main objective of case studies is to seek for answers to the questions of "how" and "why" by thorough and on-site examination of a phenomenon with intricate layers, case study method is considered suitable for this research. The only difference between a multiple case study and a case study is the examination of the topic in question not in one site but in multiple sites. This way, gaining insight as to how the phenomenon changes in similar and different contexts becomes possible and informational richness of the research, its trustworthiness and reliability increase. By including 15 different schools to the project, the study aims to benefit from this powerful side of multiple case study method. Selection of the Provinces and Schools In the selection process of the provinces and the schools included in this study, the "maximum variation sampling" method as one of the "purposeful sampling" methods has been utilized. The maximum variation sampling method can be defined as the examination of the studied 1 This paper is based solely on the authors’ individual opinions and does not reflect the opinions of the Ministry of National Education of Turkey, UNICEF Turkey and Education Reform Initiative. The authors are thankful to staff of all three organizations, and especially to Ayşe Nal and Deniz İlhan for their able assistance during the data collection and entry periods. 4 topic in sites with different features, qualities, locations, and stata, and the finding of the common patterns in these various situations (Lindlof &Taylor, 2010). In multiple case studies, this method is suggested to ensure the richness of the data gathered (Merriam, 2002). Especially when one considers that there are significant differences among regions in our country in terms of socio-economic level, the existence of young population and school types, the use of maximum variation sampling is important in revealing the different dimensions of the problem. In short, in this study, the objective is to reflect the selected schools' characteristics related to the study with the highest possible variety. The selection of the provinces and the schools included in this study has been made by taking this objective into consideration. To sum up, the selected provinces were: Şanlıurfa, where public educational expenses per student and GDP per capita are low; Karaman, where public educational expenses per student and GDP per capita are high and, at the same time, the student population comprises a large part of the total population in the; and Istanbul, which has a special status for Turkey in every way in terms of variety. The principles of maximum variation sampling method have been decisive in the selection of the schools as well. Special attention has been paid to include public primary schools with different features in the scope of the study. Therefore, five different types of primary schools including regional boarding primary schools (yatılı ilköğretim bölge okulu, YİBO), schools which operate as centers of transportation, schools with multi-grade classes, and schools operating double shifts in addition to primary schools operating single shift per day have been selected for the purposes of the study. Moreover, the number of students in the schools (over 500 and below 500) and the socio-economic status of the region in which they are located (low socio-economic status and high socio-economic status) have been determined as criteria and interviews have been made at least in one school that meets these criteria (See 5 Table 2). 6 Table 2: Participant schools in the study School type Low SES High SES Number of students Number of students 0-500 500+ 0-500 500+ Schools with single shift İSTANBUL School N KARAMAN School A KARAMAN School D İSTANBUL School P İSTANBUL School R & School S Schools with double shifts A small school operating double shifts does not exist ŞANLIURFA School G (also operates a center of transportation) ŞANLIURFA School L İSTANBUL School M A small school operating double shifts does not exist ŞANLIURFA School K YİBO KARAMAN School E (297 students) ŞANLIURFA School H (294 students) Schools with multi-grade classes ŞANLIURFA School F (181 students) Schools operating as centers of transportation KARAMAN School C (452 students) Shool B (246 students) Participants In this study, the participants can be divided into two groups. The participants in the first group are composed of various bureaucrats working in the agencies of central and local government. Through the interviews made with these actors, the macro level data of the study have been collected. The participants in the second group are the actors that affect the process of raising and spending resources in cash and in kind and are affected by the same process. Through the interviews made with these actors, the micro level data of the study have been collected. Interviews have been made with representatives who have been chosen among all kinds of stakeholders. This way, the study tries to represent different viewpoints, interests and values, and this has played a critical role in reaching a point of data saturation. 7 Data Collection Methods Macro Level Data: Three different methods have been used in collecting the macro level data of the study: First, all legal documents regulating the funding system in public primary schools have been examined. This way, the information has been collected about the role assumed by the public sector in financing the schools and division of this role among the institutions. These documents have also showed some guidance in the preparation of the interview questions. Secondly, the expenditure data on financing primary education published by relevant institutions, but mostly by the Ministry of Finance (MoF) at the national level have been examined. The data collected have been re-grouped in the context of the definitions made for the study and analyzed descriptively. Lastly, semi-structured interviews have been carried out with various actors working for the agencies of central and local government in Ankara and in three provinces where the study took place. By this way, findings about the details of the operation of the funding system have been tried to be attained. The interviewees have been detailed in Table 3. Micro Level Data: In collecting the micro level data of the study, semi-structured interviews have been utilized as the basic data collection method. Interview questions have been formed based on the researchers’ review of the legislation, previous information obtained from the literature and the pre-interviews carried out with experts. During the field research, interviews have been made with 138 people. Information about the interviewees has been detailed in the Table 4. Document analysis has also been carried out to complement the interviews. The schools' estimated budgets regarding the 2010-2011 school year and Parent-Teacher Associations' revenue and expenditure statements regarding the same period, have been examined for the purposes of this study. Especially the estimated budgets have been an important source in comparing the schools. Furthermore, the observations the researchers made during the school visits have been recorded in standardized observation forms. Finally, surveys have been sent to 1500 parents and 1306 of them turned back. With these surveys, the opinions of the parents about financing of the school have been investigated. Frequency and percentage distributions related to each question have been found out and each question has also been analyzed in terms of socio-economic status and education level of parents. In this analysis, SPSS statistical software is utilized. 8 Table 3: Participants interviewed for macro level analysis Ankara Karaman Şanlıurfa İstanbul State Planning Organization 1 - - - Ministry of Finance 2 - - - MoNE Presidency for Strategy Development 5 - - - MoNE DG for Basic Education 2 - - - MoNE Unit for Internal Evaluation 1 - - - MoNE Presidency for Coordination of Projects 1 Provincial Directorates of Education - 1 1 1 District Directorates of Education - 1 3 - Provincial Administrations (PAs) - 1 1 1 PAs’ Special Units for Providing Service for Villages - 1 1 - Social Assistance Foundations affiliated to DG for Social Assistance - 1 - - TOTAL 12 5 6 2 Table 4: Participants interviewed for micro level analysis SCHOOL A B C D E F G H K L M N P R S Principal 1 - 1 1 1 - 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Vice Principal 2 - 1 - 1 - - - - - - - - - - Acting Vice Principal - 1 - - - 1 - - - - - - - - - Rep. of PTA 1 1 1 1 1 - 1 1 1 1 1 - 3 1 1 Teacher 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 Parent 2 2 3 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 2 Student 5 2 5 2 4 3 1 4 2 3 2 2 - 3 2 TOTAL 14 8 14 7 11 8 8 10 8 9 8 7 8 10 8 9 Analysis of the Interviews The research data collected through the interviews have been examined with line-by-line method in three stages. First of all, all interviews, sound recordings and researcher notes have been transcribed, and over this transcription, open coding has been initially carried out. In the process of open coding, a concept in an interview has been listed, in the form of words or short words, as an important situation, dimension, concept or idea in the framework of the study. By being marked this way, the important data have been simplified for more detailed examination, and this way, important points regarding the research question have been put forward. In short, in this process, a key code list has been formed in order to assist the later stages of the analysis. In the second stage of the analysis, axial coding is used. The key code list formed thanks to the open coding has been examined in detail and the codes thought to have similar meanings have been combined. Later, the connection and the links between these codes are determined and the themes that explain this connection and the relations as a whole have been found out. The themes have been organized under the research questions. At last stage of the analysis, which is selective coding, the relations between the themes have been determined and a higher main theme has been developed. Division of Roles Among Various Public Institutions in Financing Public Primary Education In this section, we explain how the public spending for primary education is planned and executed in Turkey. While doing this, we would like to draw attention to the institutions involved and the relationships between them, as they would later shed light on how policies are turned into practice. At the end of the section, we describe various forms of public spending undertaken by these institutions, which we found out through review of expenditure data and relevant legislation as well as the semi-structured interviews held with bureaucrats in various public agencies. We take 2009 as the example year, because the most reliable data is available for that fiscal year. The amounts are reported in 2010 price level. Each year, budget-making process in the central government of Turkey starts with a circular order released by the Ministry of Finance (MoF). For each ministry and agency of the central government, MoF designates the upper limit of expenditures to be undertaken next year in 10 different categories of spending (such as personnel expenditure, purchasing of goods and services, investment…). As a result, MoF is a very powerful actor in the budget-making process, since transcending the upper limits put by MoF at the start of the budget-making is only an exception. The President for Strategy Development within MoNE, which acts like an office of budgeting, transfers this circular order to different DGs under MoNE, and requests them to prepare their budgets for the next fiscal year in line with the norms set by the MoF. Thus, within MoNE, primary role in budget-making is played by individual DGs, rather than an office affiliated directly to the Minister. In Turkey, teachers are directly hired by MoNE and the decision about how many teachers will be hired in the next fiscal year is up to the Cabinet of Ministers. The salaries and social security payments of teachers and other personnel in schools are undertaken directly by the central government, without any interference of local government or outposts of MoNE in provinces. The grants for non-personnel current expenditures of public primary schools (except those of regional boarding schools) are transferred by MoNE to Provincial Administrations (PAs) in each of 81 provinces of Turkey. PAs in Turkey are constitutionally local governments with elected councils but the governor who is responsible for executing the decisions taken by the elected councils are appointed by the central government in Ankara. Thus, PAs can be classified as a hybrid organization between local government and outpost of central government. The grants received by PAs from MoNE for non-personnel current expenditures of schools are mainly used to pay water, electricity, heating and telecommunication bills. PAs directly pay those bills for schools without transferring any funds to the schools. The grants transferred by MoNE also includes lines for purchases of materials and equipment and smallscale maintenance and reparation works, but schools we have visited for this study reported that they very rarely receive such goods or services from PAs. The bureaucrats of PAs we interviewed openly stated that undertaking current expenditures of public schools increased the workload and they perceive it as an unnecessary burden. Compared to the provincial directorates of education (PDEs) they do not see themselves as the “owners” of schools. Therefore, they do not take spending decisions on the funds transferred from MoNE, without the written request of PDEs through the governor. This clearly complicates the execution of spending decisions. 11 When allocating the grants for non-personnel current expenditures to provinces, MoNE uses different formulae for each line item. For instance, number of students in that province is taken into account for the allocation of the grant for “Water Purchases”, whereas number of classrooms is used for the allocation of the grant for “Electricity Purchases”. Each province has a “point” for climate, which increases as the province gets colder, i.e. its need for “Purchases of Heating Goods and Services” increases. One can conclude that this complicated system has been elaborated throughout the years to allocate scarce funds to provinces in the most efficient way possible. The grants of investment expenditure are also transferred by MoNE to PAs. PAs are much more comfortable in taking spending decisions for the grants for investment expenditures. By the Law on Primary Education they have to allocate 20% of their own budget to primary education, as well. The bureaucrats we interviewed in PAs stated that they mostly use their own funds for investment expenditures. The allocation of investment grants from MoNE to provinces are legally based on the proposals collected from PDEs, but the decisions are mostly made through bargaining behind closed doors which also involves MPs, as these grants are mostly used for school building. The cities and towns in provinces have municipalities as a form of local government whose all decision-making organs are elected. Municipalities are not obliged to participate in the expenditures for public education, but they are allowed to cover non-personnel current and investment expenditures of schools if they are willing to do so. As opposed to thousands of public primary schools which do not receive any public fund in cash, regional boarding schools do receive public funds to cover the expenditures of their dormitories. These are the only schools which have some autonomy on how to spend the funds they receive from the central government. The expenditures made for transportation of students in rural areas are undertaken by PDEs through the funds transferred by MoNE. School meals in Turkey are only provided for those students who are bussed to schools every day. The funds for school meals are transferred from the Directorate-General for Social Assistance (DG-SA, which is affiliated directly to the Office of the Prime Minister) to PDEs. 12 DG-SA is an important public agency in the funding system of primary education because it mainly provides the funds for the scholarships and aids directly to students. Among the programs covered by the DG-SA are conditional cash transfers and the aid for educational materials. These programs are executed by Social Assistance Foundations established as the outposts of the DG-SA in each province and district of Turkey. DG-SA also supplies the funds to the central organization of MoNE through which MoNE purchases textbooks for each public primary school student in Turkey and distributes them to each school. The increasing role of DG-SA will be discussed in more detail below. To complicate the picture even more, there are also grants transferred from MoNE to Housing Development Agency (HDA), another agency directly affiliated to the Office of the Prime Minister, so that it can build public primary schools. Table 5 summarizes the categories of public spending in primary education, and the amounts spent for each category. Briefly, the table suggest that the central government is mainly involved for undertaking the expenditures for the (teaching) staff and providing aids and scholarships for students in need. To increase the rates of enrolment especially in rural areas, important amounts of funds are spent for transportation and current expenditures of regional boarding schools. Yet, the institution which loses in this environment is the (non-boarding) public primary school. In order to be able to share the burden of current expenditures of these schools, central government transfers the grants for these expenditures to PAs and enforces them by law to make contributions for current expenditures, yet PAs are unwilling to take the responsibility for public primary schools. The funds are also indeed scarce (400 million TL for more than 32,000 individual schools) which is hardly enough to pay the regular bills, let alone undertaking discretionary spending. The gap is covered by the additional funds from the budget of PAs, most probably only in provinces where there is no more need for more classrooms and schools and where PA and the PDE can work in harmony. The details of the flow of funds can be seen in Figure 1 below. The consequences of this funding system structured around public primary schools will be discussed in the next section through findings gathered via case studies of 15 different schools. 13 Table 5: Categories of public spending for primary education and expenditures in 2009 Category of spending Expenditures in 2009 (in 2010 TL) Expenditures for staff (paid directly by MoNE to the staff) Share in total 12.567.161.603 73,2% 1.473.798.839 8,6% Non-personnel current expenditures for schools (Grants transferred by MoNE to PAs) 395.775.131 2,3% Capital expenditures (Grants transferred by MoNE to PAs) 469.342.540 2,7% Expenditures undertaken by PAs and municipalities with own sources (Non-personnel current and investment) (mostly used by PAs for investment) 496.849.092 2,9% Non-personnel current expenditures of boarding schools (Grants transferred by MoNE to boarding schools) 204.563.015 1,2% 83.197.165 0,5% Expenditures for transportation of students in rural areas (bussing and school meal) 682.632.528 4,0% Aids and scholarships (mainly by DG-SA directly to students) 730.612.043 4,3% 64.211.960 0,4% Social security expenditures for staff (paid directly by MoNE to Social Security Agency) Transfers for capital expenditures (Grants transferred by MoNE to HDA) Other expenditures by the central government Sources: Authors’ calculations based on Bulletins of Public Accounts available online at the website of Ministry of Finance Directorate General for Public Accounts; Database on Expenditures of Ministry of National Education, 2005-2009 (shared with ERI); Expenditures of MoNE in 2010; Annual Report of Directorate General for Social Assistance 2010; Presentation of the Minister of National Education on 2012 Budget. Sources and explanations for Figure 1 (next page): Authors’ findings based on review of legislation and interviews with bureaucrats in public agencies of central and local government. Arrows with dashed line symbolize spending of funds whereas arrows with flat line symbolize transfer of grants from one agency to another. Abbreviations in Table 5 and Figure 1: MoNE: Ministry of National Education, DG-SA: Directorate General for Social Assistance, PA: Provincial Administration, HDA: Housing Development Agency; SPO: State Planning Organization; SAF: Social Assistance Foundation; PDE: Provincial Directorate of Education. 14 Figure 1: Flow of public funds for primary education from and to various agencies MINISTRY OF FINANCE DG-SOCIAL ASSISTANCE DG-SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MoNE / SPO MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION Contri-bution of PAs Contribution of Provincial Administations (PAs) PROVINCIAL DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION / PROVINCIAL ADMINISTRATION PDE / PA DISTRICT DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION / OUTPOST OF PA IN DISTRICT HDA SAF PERSONNEL EXPENDITURES CURRENT EXPENDITURES: EDUCATIONRELATED CURRENT EXPENDITURES: OPERATIONAL TRANS -FERS BUILDING SCHOOLS LARGE-SCALE REPAIRMENT AIDS/SCHOLARSHIPS SCHOOL MEALS ACCOMMODATION TRANSPORTATION TELECOMMUNICATIONS WATER/ELECTRICITY/ HEATING CLEANING SMALL-SCALE MAINTENANCE AND REPAIRMENT EXTRACURRICULAR ACTIVITIES PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF TEACHERS EDUCATIONAL MATERIALS (Durables for school) EDUCATIONAL MATERIALS (Textbooks and stationery) NON-TEACHING PERSONNEL TEACHERS BOARDING SCHOOLS CAPITAL EXPENDITURES 15 School Level Analysis across 15 Case Studies As has been explained in detail at the macro level, the salaries of teachers and some expenditures of schools namely electricity, water, and heating are covered by the central government in Turkey. There is, however, no budget allocated to the schools for other expenses. Therefore, schools have to generate their own revenue and depend largely on the donations made by parents and other contributors. With the Bylaw on Parent-Teacher Association that entered into force in 2005, the state almost officially approved this situation. According to the Bylaw, accepting parents' donations, organizing revenue creating activities, and taking advantage of opportunities for revenues already existing in schools, are legally defined as the responsibilities of the Parent-Teacher Associations (PTA). According to this bylaw, every school must have a Parent-Teacher Association that takes on these responsibilities. Therefore, the main purpose of this analysis at the school level is to examine both monetary and in-kind resources raised through PTAs. More specifically, the following three questions are answered in this field research: In public primary schools, how does the process of raising monetary and in-kind revenue from private sources work? In public primary schools, how does the process of spending of monetary and in-kind funds from private sources work in practice? What are the perceptions of stakeholders in primary education with regard to the practices in financing primary education? The data set for obtaining findings at the school level were acquired through parent surveys and face-to-face interviews carried out by 138 interviewees at 15 schools in three different provinces. In the following section, the findings of the field research carried out in 15 schools are presented in detail. The Private Giving Received by Schools Fully understanding the private giving received by schools is an issue of both policy-making and equity and also understanding them provides whole picture of funding system of primary 16 education. Therefore, in following, we describe the types of private contributions to public primary schools. These are emerged as: parents’ donations, donations from out-of-school people or entities, revenue received from the rental of school property and special activities, and finally the municipal aids. Although municipal aids should be considered public spending, we give the details under the heading of “private giving”, since our data revealed that interpersonal relationships play a significant role in schools obtaining municipal aid. Parents’ Donation: In Turkey, the eight-year compulsory education is free of charge in public schools by the Constitution. Therefore, requesting money from parents is illegal. In the beginning of every school year, the media takes up the issue that legal action will be taken against the principals who demand money from parents. In the same way, parents cannot be forced to make donations according to the Bylaw on Parent-Teacher Association. Yet, the findings of the field research suggest that, despite all the sanctions foreseen in legal documents, in general meetings of the Parent-Teacher Association, the amount of donations in cash that will be demanded from parents during the school year, is determined and parents are asked for donations. These contributions are put on the records of the PTA as “voluntary donations from parents.” The amount of donations demanded from parents change depending on the average socio-economic level of parents. For instance, in our sample, schools located in wealthy neighborhoods demanded 600 TL per student from parents, for schools in poorer areas, this amount goes down to 5 TL per year. During the interviews it is stated that since parents are not legally obliged to finance schools, they refuse to pay these contributions. This finding is confirmed by parent surveys. For instance, 67% of the parents who identify themselves in the low socio-economic income group and 55% of the middle and high socio-economic income group do not approve that the needs of the school are met with the contribution of the parents. School principals, being otherwise helpless to address this issue, bring forward the issue of financing the school expenditures, in the environments where more social pressure is exerted on parents. For instance, parents’ meetings are considered as a way of collecting money from parents. 42.5% of the parents noted that, in parents' meetings, money is collected for the needs of the school. Moreover, %17 of the parents expressed that they do not attend parents' meetings for this reason. In short, parents' meetings go beyond their scope. As for teachers, they are held responsible by the school administrations for collecting these contributions and 17 informing parents through students about the contributions they have not paid. Teachers expressed that this situation is not in accordance with occupational ethics, yet they are forced to do it. 14% of the parents stated that they verbally argue with teachers or school administration due to this demand for money. Another type of donation collected from parents is registration fees. In Turkey, parents have no right to choose the public schools they want. Each student has to go to a school in his/her own neighborhood. Yet, even if it is limited, schools have a certain quota for students living in neighborhoods outside their official area. Since it is believed that the quality of education in wealthy neighborhoods is high, schools in these neighborhoods are in high demand. They accept students living outside their zone and, despite its being illegal, these schools demand registration fees as donations. The schools located in areas with a low socio-economic status are not able to generate revenues this way. This is one of the factors that affect the revenue difference between the schools in wealthy areas and the schools in areas with a low socioeconomic status. According to the research findings, in the schools in wealthy neighborhoods, apart from the registration fee, contributions in cash are expected to be paid throughout the year, and there is also a demand from parents for furnishing the classrooms. The parents of the students who are about to start first grade raise money among themselves and purchase technological appliances such as computers, smart boards and projectors, acquire photocopy papers and supplementary textbooks, and provide needs such as curtains or air-conditioners. This way, classrooms equipped with quality instruments are formed. On the other hand, in the schools in areas with a low socio-economic status visited in the scope of this study, there are only seats and a board, and even photocopy papers are very limited. In order to avoid expenditures, the teachers cannot ask for supplementary textbooks and they even reserve some of their own budget in order to be able to cover the expenses of the classroom. The students attending primary schools in areas with a low socio-economic status are already deprived of this type of opportunities in the households they live and in their social environment. The same deprivation continues at school as well and the schools’ capacity of bridging the social inequality is limited. Out-of-School Donors: International organizations, non-governmental organizations, national organizations, local associations and corporations also provide schools with donations in cash 18 and in kind. However, it is found that the donations by these types of organizations are made according to the viewpoint or the organizational vision and agenda of the organization that provides the donation. The most important finding about acquiring these types of donations is that an individual's relations, personal initiative, activeness, and assertiveness all play an important role. The relationship with the donors depends not on the relationship between institutions, but on individual's relations, the skill or the will of the individuals to take initiative. On the other hand, this means that, in the event that the school stakeholder who sets up the connections with the donors and the institutions leaves the school, the revenues coming from these donors will stop. Therefore, it is not possible in the current situation to talk about a sustainable relationship between donors and schools. For this reason, the more successful the school stakeholders are in their initiatives to generate revenues for the schools’ needs, the more opportunities the schools have. And according to stakeholders this creates the perception that a principal who obtains funds for the school is a successful one, whereas a principal who cannot achieve this is an unsuccessful one. Principals state that what matters now is not how good an educational leader they are but whether they can raise revenues for the school. For this reason, principals spend most of their time to collect funds from potential donors and they expressed that their effort to find monetary and in-kind resources for the school is taking up the time they could have spent on being an educational leader. When the situation is examined in terms of revenues provided by external donors, it is possible to say that schools do not have a foreseeable revenue flow. More importantly, that some schools are more fortunate in terms of external donors while other schools are not is a factor that deepens the inequality gap between the schools. Revenue received from the rental of school property: In the research, it has been determined that some primary schools have operating revenues from three different sources: rental revenues acquired from renting of the canteen, the sports hall and the parking area. The main finding related to the operating revenues is that, although operating revenue is important revenue for schools, not every school has the opportunity to benefit from this type of revenue. For instance, the schools in poor neighborhoods do not have canteen rental revenues or the revenues is lesser compared to the schools in wealthy neighborhoods. Since the potential total student spending in a canteen is an important criterion in determining the monthly rental value 19 of a canteen, the schools in areas with low socio-economic status cannot benefit from canteen revenues as much as the schools in areas with high socio-economic status. The reason why there is no canteen in some schools is that in these schools, the canteen does not bring much income and so there is no one willing to run the canteen. In the same way, some schools can get revenues from renting of the parking area, the sports hall or the conference halls. Yet, it has been found out that only the schools in richer neighborhoods can benefit from these types of revenues. In the schools located in poor neighborhoods, there are either no such spaces or they are not adequately equipped for rentals. In schools where there are no sports hall and conference hall, the students are already deprived of many opportunities due to the lack of such spaces. On the other hand, schools with such facilities can both offer their students various opportunities and obtain revenues by renting these places outside educational hours. Therefore, it is possible to talk about a two dimensional inequality here. Special Events: The Bylaw on PTAs designates that schools can raise revenues through social, cultural and sport activities, courses, projects, campaigns and such. Among the schools examined only four of them expressed that they organize fairs, dinners for parents, trips and theatre plays, and raise a certain amount of revenues from these activities. When the schools that have institutionalized these organizations are examined, it is observable that these schools are the schools with the highest socio-economic status. This type of activities requires pre-planning, a serious organization -especially in crowded schools-, volunteers for the organization and financial contribution of parents. When the situation in question is evaluated with the fact that, in the schools in areas with a low socioeconomic status, Parent-Teacher Associations are not working as projected, the connection between parents and the school is not established and the income profile of the parents are low, it is understandable that raising funds through these types of special activities does not appear as a viable alternative for the schools in areas with a low socio-economic status. Among the activities the school carries out to generate revenues is issuing a school magazine. Thanks to the ads published in the school magazine, the school can have some revenue. The sales of these ads are made through the teachers. However, teacher participants of this study 20 believe that it is not appropriate to force them to perform a task that is outside their job definition for generating revenues. Municipal aids: It has been determined that all the schools in the scope of this study have been receiving similar type of aids from municipalities. All the principals expressed that they receive assistance from the municipalities in issues such as asphalting the school garden, pouring of sand to the playground, placing benches inside the school, putting up the school wall and maintenance of the school wall, cleaning of the sewer system, and maintenance of the trees in the garden. Although municipalities provide the above-mentioned services, there is no continuity in their services. In other words, municipalities do not maintain school gardens periodically but provide this service only upon the request of the schools. The personal relationship of the principal or the other members in the school to the municipal or the role of the parents who work at municipality play in making this task easier, are important factors determining whether the services the school demanded will be provided and/or, if they are provided, whether they will be provided on time. On the other hand, some municipalities provide the schools with their services without any demand. Some of the schools in the study described these municipalities as "school-friendly" municipalities because of their attitude. For example, one municipality provided the school with a full-time security guard and regular services for the cleaning of the school garden. Another municipality takes the students and the teachers to theatre and cinema regularly, and renews the school library. These are good examples of "school friendly" municipalities. The findings related to the municipality-school relations prove that the services the municipalities provide for the schools and their general policy related to the issue, create a difference in terms of facilities offered to the students. The Role of Parent-Teacher Association So far, the ways the schools raise their own revenues have been discussed in detail. As mentioned above, the executive board of PTAs is responsible for obtaining and spending these revenues, and principals are members of this board. For this reason, the operation of PTAs is examined closely to be able to understand the issue under investigation. With the 21 Bylaw on Parent-Teacher Association that entered into force in 2005, PTAs became the sole responsible body in raising and spending revenues, operating the places belonging to the school. According to the Bylaw, the parents who will preside over the association and the parents who will take part in the executive board of the association shall be assigned by election. According to the findings of the field research, various difficulties are experienced in forming and operating of PTAs in the way defined in the Bylaw. The greatest of these difficulties is the problems experienced during the election of the members of the board. It has been observed that, in practice, in the schools located in poorer areas, parents are reluctant to take an active part in parent-teacher associations. Faced with this situation the principals persistently request to take an active part in the PTA, especially those parents who are personally too close to reject them, or those parents who have personal connections with potential donors. Therefore, taking part in the parent-teacher association has become a chore done as a favor instead of depending on choice and willingness. This forced formation of the PTAs results in an association that cannot perform its functions. According to the statements of the principals, the president of the PTA only visits the school on demand of the school administration when there is a document to be signed. Therefore, it is not possible to say that they take part in the decision-making process about school budget or that they perform the duties stated in the Bylaw. For this reason, principals and vice principals take on the duties and responsibilities PTAs are supposed to take. Apart from increasing the workload for the school administration, this also raises questions about the existence of parent-teachers associations. Moreover, due to the weakness of parent-teachers associations, principals have become the person with the most influence over decisions about how to spend monetary donations. According to the school stakeholders, the primary reason why difficulties are experienced in forming the boards of PTAs and that they are units that cannot perform their functions, is the weak connection between the schools and the parents in Turkey. On the other hand, since taking an active part in PTA includes such chores as collecting donations, signing purchasing 22 decisions, and taking money out of the bank even for minor purchasing decisions, the parents tend to avoid this. As can be inferred from the findings above, it is possible to say that, in Turkey, elementary schools differ a lot in terms of the revenue they get. Expenditures per student change as well. For instance, among the 15 schools in the study, one school spends 11 TL per student annually, while this number rises as high as 457 TL in another school. Considering that in Turkey 1.780 TL is spent by the public agencies per student annually in 2009 (in 2010 prices) by public funds at elementary school level, the significance of this difference can be better understood. When we also look at school-district relationship in terms of financial issues, it is seen that school districts (provincial and/or district directorates of education) also have very limited amount of resources and since this fact is known by the schools, principals do not even attempt to ask any monetary or in kind help from the districts. Even if schools ask any financial help such as contribution to small-scale repair and maintenance, school districts do not respond timely to the request. Stated by the school administrators, it might take directorate years to meet these requests. Neither is there a transparent approach to the prioritization of these requests. Moreover, schools are required to pay 20% percent of their own revenue to provincial/district directorates, assuming that they can play a regulatory role to compensate disadvantaged schools by using the money collected from individual schools. However, it is indicated during the interviews with both school administrations and officials from district directorates, that in practice this does not happen: the money collected by directorates is spent on the needs of the directorate since the government also does not allocate any budget for district use. In short, public primary schools become fully dependant on private giving. As the result of the situation detailed above, the schools that can raise private revenues have richer opportunities in terms of the variety of extracurricular activities, while the schools with no revenue lack this type of opportunities. In the same vein, the schools with revenues can employ cleaning and security personnel, diversify their educational materials and provide high-tech classrooms and a more hygienic school environment. In schools with low revenues, even the most urgent needs such as repair of school toilets or a broken classroom window are hardly covered. 23 Consequences of Which Policies? Policies Leading to the Current Funding system of Primary Schools in Turkey Previous sections of this article focused on how the funding system of primary education in Turkey worked, and which consequences this mechanism generates especially at the school level. In this section, we will focus on the policies shaping this mechanism, as they are very important to the basic question of this article, namely whether public funds are insufficient to meet the needs of primary schools in Turkey and/or the funding system is inadequate. The policies we focus on are the increasing role of the Provincial Administrations (PAs) without accompanying accountability mechanism, the acknowledgement of the importance of private contributions for current expenditures through the renewal of the Bylaw on PTAs which can be deemed as quasi-privatization and increased spending on transfers to individual students while transfers for school expenditures stagnate. We witness that all of these policy inclinations strengthened in the last decade. Decentralization to Provincial Administrations As we mentioned before, PAs are responsible for undertaking the non-personnel current expenditures for public primary schools’ needs without the transferring the funds to school administration. Since 1960s, PAs were responsible for undertaking capital expenditures for primary education as they had to contribute to public spending for primary education with 20% of their own budgets. Throughout the years, PAs began to undertake the procurement and purchasing work for current expenditures for primary schools as well, in collaboration with provincial directorates for education (PDEs). In 2005, the law regulating PAs changed to strengthen the local character and capacity of PAs. As a result of this process, PAs undertook all non-personnel current expenditures of public primary schools except regional boarding schools which receive public funds in cash from central government directly (Türkoğlu, 2004). In 2003, the government started a process towards decentralization by passing a series of laws on public administration in Turkey through the Parliament. It was the plan of the government to abolish the local organization and outposts of MoNE in provinces, namely PDEs, and transfer them to the control of the PAs entirely. Yet, the basic pieces of laws towards decentralization were subject to intense public discussion and also to the veto of the president, and the abolition of PDEs never came into effect. On the other hand, the law on PAs changed 24 successfully and they were strengthened in terms of both local character and capacity: The elected council’s decision-making power and human resources to be employed by PAs increased (Çiftepınar, 2006). The reflection of this change in primary education sector was the increase of the role of PAs in undertaking current expenditures of primary education schools. MoNE began to transfer all grants for current expenditures of public primary schools to PAs. Although the grants were earmarked, i.e. MoNE had designated for which purposes the grants were to be used, it was up to the local discretion which districts of the province and which schools will be prioritized, especially for the grants for small-scale maintenance and repairs and for purchasing school durables. Yet, PAs were unwilling to decide on how to use these grants, although the decision-making capacity of the elected council of the PA was increased by law. In practice, PAs wait for the written requests of PDEs to use these grants. When we asked why this is the case, bureaucrats at both PDEs and PAs told that the schools still belong to the MoNE and PAs are not in a position to decide which schools’ needs should be prioritized. Moreover, in line with the findings of Türkoğlu (2004) PAs still lack sufficient human resources to run the whole operation for non-personnel current expenditures of schools and they require the support of the personnel of PDEs. In two of three provinces we visited, members of the staff of PDEs were in practice working full-time at the offices of the PA. This situation, in practice, leaves PAs in a position in which they are not held accountable for the decisions they make. Using the accountability framework introduced in World Development Report 2004 (World Bank, 2004), the lack of accountability on the part of PAs can be shown in a clear way. According to the WDR, “where the state and the public sector are involved, voice (the accountability mechanism citizens exert on policymakers) and compacts (the accountability mechanism policymakers exert on providers of public services) make up the main control mechanism available to the citizen in the long route of accountability” (Devarajan et al., 2007) (see Figure 2). Yet, PAs in the Turkish funding system for primary education are exempt from both of these accountability mechanisms. Many citizens do not even know that they have a role in the financing of education in Turkey and they cannot be held accountable by the MoNE whose grants they use because they are institutions of local government not to be held accountable by the agencies of the central government. This leaves PAs in a strange position as shown in Figure 3. 25 Figure 2: The accountability framework of World Development Report 2004 Source: Devarajan et al., 2007. Figure 3: The long accountability route in funding system of Turkish primary education and the place of Provincial Administrations Central government / Ministry of National Education COMPACT COM PACT Provincial administrations VOI CE Provincial Directorate of Ed. (Outpost of MoNE) VOICE CO MP ACT Citizens Providers Source: Authors’ evaluations and findings using the framework of Devarajan et al. (2007). Cognizant of this strange situation, PAs require the requests of PDEs to use the grants for primary education. Yet, this clearly complicates the procedure for spending public funds especially for the grants in which discretion of an accountable decision-maker (such as prioritization of some schools for the use of the grants for small-scale repairs and 26 maintenance) is required. This situation, which can be labelled as “partial decentralization” in which citizens do not hold local governments accountable for the decisions the make and in turn local governments do not try to increase their capacity to allocate budgetary resources optimally across competing needs (Devarajan, 2007), increases the dependency of schools on private contributions coming through PTAs. Quasi-Privatization Both the macro and micro level analysis of this current study revealed that public resources are mainly used to pay teacher salaries, and public elementary schools receive any public fund in cash from the government. Therefore, public primary schools are dependent on private sources to run the schools. It is important to note that in current situation it is not possible to examine the size and distribution of voluntary contributions to public primary schools at the national level. This is due to the fact that there is no such mechanism that tracks how much revenue individual schools receive from private entities. Even though there is no way to investigate the whole picture on revenue, our school-level investigation shows that since primary schools are short on money for everything from basic classroom needs to cleaning personnel, public schools across the nation are seeking donors, grants and ways to utilize their gyms, canteens and conference rooms to obtain some rental income for the school. We argue that, in this sense, Turkish primary education is not purely public. It is much more like a quasi-public. Although there is not enough research about school funding in Turkey, in two recent articles, it was also indicated that since school funding relies heavily on private contributions and no regulatory monitoring by the state means on how the schools use private revenues they raise there is “quasi-privatization” in primary education in Turkey (Yolcu & Kurul, 2009; Candaş et al., 2011). The government has been reinforcing this quasi-public funding system formally since 2005 by renewing the Bylaw on Parent Teacher Associations. Even though private funds supporting public primary schools were known before this, in 2005 the Turkish government legitimized the need for pursuing private support to finance education with the constitution of the bylaw. Moreover, this bylaw required each school to pay 20% of their revenue to province/district directorates of education, assuming that school districts can play a regulatory role to compensate disadvantaged schools by using the money collected from individual schools. However, as this study revealed, in practice this does not happen: the money collected by 27 PDEs is spent on the needs of that particular PDE, since the government does not allocate any budget for the use of PDE, either. In short, public elementary schools become fully dependant on the PTAs’ revenue. When this bylaw is looked at closely, creating a PTA becomes mandatory in every public primary school and there are many financial duties defined for the executive board, including organising fundraising activities, accepting in kind and in cash supports and operating or renting of the school’s gym, canteen, etc. By the hand of the government, they are becoming liable for funding some activities and equipment, such as repair and maintenance of the school, renewing facilities in common areas (labs, library), building extra classrooms, providing teaching materials, and supporting school-wide special events. Furthermore, with the PTA becoming the only organ that is responsible for funding schools there is no governmental vehicle to monitor schools in terms of how much money an individual school is raising and how school money is being spent. This paper supports the idea that this system leads to a quasi-public financing system and it creates two unintended consequences. First of all, in the case of Turkey, the school-level data analyses suggest that, except the grants for regional boarding schools and bussing in the rural area, there is no funding which could have compensated for the inequalities between schools. Schools in affluent areas have an advantage in obtaining financial support from parents and municipalities, finding private donors and obtaining diverse revenues. All these factors exacerbate inequities in the classroom. It is also possible to expand this argument and say that the current school funding system exacerbates inequities in Turkish society since the state does not play any regulatory role to compensate the disadvantages of poor schools. Although there are many concerns stated in the literature about private donation increasing the inequalities between schools, Zimmer, Krop, Kaganoff, Ross and Brewer (2001) found in their study conducted in Los Angeles County that despite schools in poor communities not getting as much monetary and in kind contributions from parents as those in wealthy communities, they attract more philanthropists and corporations, hence they are able to close the financial gap. However, our study shows that, due to the amount of money a school gets from private donors mostly depending upon personal contacts and school principals’ assertiveness, wealthy schools can still benefit more from donations from philanthropists and corporations. 28 Second, a micro-level case analysis of 15 schools shows that even though the PTA board is described as the main decision making organ on spending of the school budget, in reality, since PTAs are so weak, school principals become the only decision-makers on how to spend the school budget. The principals assume full authority and have full autonomy over the money, without any accountability to the local government or parents. As a result, how efficient the school uses the money has become totally person-dependant. Although in the literature it is indicated that the contribution of parents and community to the school budget leads to stronger governance and management and fiscal discipline in schools since philanthropists insist on results after making donations (Colvin, 2005), in our investigation we could not find any evidence that donors or PTAs have active, hands-on involvement in decision-making processes. Preferring Transfers to Individuals Over Grants to Schools The fact that public primary schools in Turkey experience a great deal of problems of financing and have to resort private contributions from parents and other donors through PTAs may lead one to think that public spending on primary education in Turkey is decreasing, or at least, stagnating. Yet, the figures in Table 6 suggest the opposite: From 2006 to 2010, public spending for primary education increased (in fixed prices) from 13.9 billion TL to 18.3 billion TL, and per student spending rose from 1,359 TL to 1,780 TL. So where did the money go? First of all, it is remarkable that the expenditures for personnel have went up. Indeed, the student/teacher ration in primary education went down from 27 in 2005-2006 to 22 in 20092010 (ERI, 2011), which seems to be a reasonable way to increase spending as the average in OECD countries was 16 in 2008 in the same level of education (OECD, 2008). Other remarkable category of spending in Table 6 is the aids and scholarships mainly undertaken by Directorate General for Social Assistance (DG-SA), which is not part of MoNE and directly affiliated to the Office of Prime Minister. DG-SA uses a special fund which is not under the control of the Ministry of Finance. The revenues of this fund come from various sources of direct and indirect taxation and the percentages transferred from categories of taxes to the fund is up to the discretion of Council of Ministers. The DG has also a special way to spend the fund: In each province and district of Turkey a “Foundation of Social Assistance” is established by law whose executive board is composed of the directors of outposts of central 29 government agencies in that district. This board decides how to use the funds granted by the DG-SA in Ankara and which families and children should receive aid and scholarship. As seen in Table 6, the spending from the sources of DG-SA for public primary education increased fast. This spending mainly takes three forms: (1) Each year, DG-SA transfers approximately one-third of its contribution to primary education to MoNE, so that MoNE can purchase textbooks for each student in primary education and distributes these textbooks to schools on the first day of the school year. (2) Another one-third of spending goes to foundations of social assistance under the heading of “Aid for Education Materials”. This aid is awarded by the foundation in cash or in kind to families which is deemed by the foundation as in need of support for purchasing education materials in the beginning of the school year. (3) Approximately one-third of spending goes to “conditional cash transfers” in primary education. This is a program which was recommended to Turkey by World Bank during the 2001 financial crisis to ensure school attendance. Accordingly, the mothers of children in the poorest segment of the society who regularly attend schools receive monthly payments. Again, who will receive the payment is up to the decision of the board of foundation, but conditional cash transfers are subject to much more detailed and objective conditions. We do not claim that spending on transfers to individual students is unnecessary and only populist. We just suggest that the government in Turkey has had the tools to increase spending on public primary education in Turkey, and it preferred to do that by increasing in cash or in kind transfers to individual students rather than increasing the grants awarded to provinces or schools. Coinciding with other policies of the government around 2004 and 2005, this led to further weakening of schools as education institutions. The government assumed that schools should be able to raise revenue to meet their needs, while it provides the teachers and ensures that children are attending schools through various forms of individual transfers. 30 Table 6: Public spending on primary education in Turkey from 2006 to 2010 (in Turkish Lira, in 2010 prices) 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Expenditures for staff 9.813.410.494 10.961.316.334 11.297.061.742 12.567.161.603 13.018.929.485 Social security expenditures for staff 1.198.845.963 1.322.638.452 1.346.919.327 1.473.798.839 2.242.980.638 Non-personnel current expenditures for schools (Grants transferred by MoNE to SPAs) 337.826.159 340.748.546 345.494.030 395.775.131 351.996.701 Capital expenditures (Grants transferred by MoNE to SPAs) 748.174.229 847.936.570 580.460.744 469.342.540 537.800.745 Expenditures undertaken by SPAs and municipalities with own sources (Non-personnel current and investment) 261.701.761 314.424.599 399.333.808 496.849.092 399.933.554 Non-personnel current and capital expenditures of boarding schools (Grants transferred by MoNE to boarding schools) 250.188.746 260.522.426 225.111.518 204.563.015 224.922.110 Transfers for capital expenditures (Grants transferred by MoNE to HDA) - - 28.403.318 83.197.165 150.000.000 Expenditures for transportation of students in rural areas (bussing and school meal) 619.969.181 622.703.876 615.418.897 682.632.528 668.500.000 Aids and scholarships (mainly by DG-SA directly to students) 598.044.107 605.073.071 643.097.411 730.612.043 603.232.753 Other expenditures by the central government 47.118.632 51.063.843 67.089.891 64.211.960 57.150.016 TOTAL PUBLIC SPENDING 13.875.279.274 15.326.427.718 15.548.390.685 17.168.143.915 18.255.446.002 Number of students in public primary education 10.209.844 10.330.690 10.316.056 10.107.614 10.257.169 Per student spending in public primary education 1.359 1.484 1.507 1.699 1.780 Sources: Authors’ calculations based on various sources (see Table 5). 31 Conclusion In this study the financing of primary education was examined at both policy and school levels and the process was taken as a whole. This holistic nature will help actors playing key roles in policy and strategy development to address the issue from a wide angle. Going through the relevant literature we came across no other comprehensive study on the financing of primary education in Turkey as the present one does. Thus, we hope the study also fills an important gap in literature. Although Turkish government define its responsibility to fund public education, current funding system is not positioned to maximize equality of opportunity for all. We conclude that, some government policies worsen this situation. These are decentralization policies which failed due to lack of functioning accountability mechanisms, spending decisions preferring transfers to individual students over grants to schools, and the funding system which is at least partially privatized. Relying on private contributions to close budget deficits in funding public schools and on transfers to students is not a panacea for improvement of education system. In addition to preferences of the central government, nearly all of the private contributions are spent for “lower leverage” activities such as buying additional resources and equipments offering no pedagogical or curricular innovation (Hansen, 2007). Those lower leverage spending do not bring any systematic improvement to the whole education system. What we rather need is investment on research and advocacy to foster educational quality (Hansen, 2007). Otherwise, it would be violating the basic right of our children to receive a quality education. Turning back to one of the basic questions of this article, namely whether Turkish education system suffers from insufficiency of public funds on primary education or rather from inadequacy of the funding mechanism, we can claim that we have evidence for both. First, 1,600-1,700 TL public spending per student/year, especially taking into consideration that 40 TL for non-personnel current expenditures per student/year, cannot be deemed as sufficient. In addition, the place of PAs in the funding system exempt from any kind of accountability, the increasing role of DG-SA and the non-existence of schools in making decisions on spending public funds, suggest that the funding system is not as rational as it could have been. Thus, the system needs a complete overhauls from both aspects. 32 References Altuntaş, S. Y. (2005). İlköğretim Okullarının Finansman İhtiyaçlarını Karşılama Düzeyleri. Unpublished master’s thesis. Yüzüncü Yıl University. Candaş, A., Ekim-Akkan, B., Günseli, S., and Deniz, M. B. (2011). Devlet İlköğretim Okullarında Ücretsiz Öğle Yemeği Sağlamak Mümkün mü?. İstanbul: Open Society Foundation. Çiftepınar, R. (2006). “Yeni İl Özel İdaresi Yasası’na Eleştirel Bir Bakış”. Yasama, 2, 123-145. Colvin, R. L. (2005). “A New Generation of Philanthropist and Their Great Ambitions” in Frederick M. Hess, ed., With the Best Intentions: How Philanthropy is Reshaping K-12 Education, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press. Devarajan, S., Khemani, S. and Shah, S. (2007). The Politics of Partial Decentralization. The World Bank. ERI (Education Reform Initiative) (2011). Education Monitoring Report 2010 Executive Summary. Istanbul: Education Reform Initiative. Hansen, J.S. (2007). “The role of nongovernmental organizations in financing public schools.” In E. Fiske & H. Ladd (Eds.), Handbook of research in education and policy. New York, NY: Routledge. Kavak, Y., Ekinci, E. and Gökçe, F. (1997). “İlköğretimde Kaynak Arayışları”. Eğitim Yönetimi, 3 (3), 309-320. Koç, H. (2007). “Eğitim Sisteminin Finansmanı”. Gazi Üniversitesi Endüstriyel Sanatlar Eğitimi Fakültesi Dergisi, 20, 39-50. Lindlof, T.R, and Taylor, B.C (2010). Qualitative Communication. Research Methods (Third Edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Merriam, S. B. and associates (2002). Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. OECD (2008). Education at a Glance 2008. Paris: OECD Publishing. OECD (2010). Education at a Glance 2010. Paris: OECD Publishing. OECD (2011). PISA 2009 Results: What Students Know and Can Do. Paris: OECD Publishing. Özdemir, N. (2011). İlköğretim Finansmanında Bir Araç: Okul-Aile Birliği Bütçe Analizi (Ankara Örneği). Unpublished master’s thesis. Hacettepe University. Türkoğlu, R. (2004). “Eğitimde Yerelleşme Sorununa Kamu Yönetimi Temel Kanunu Tasarısı ve Yerel Yönetim Yasa Tasarısının Getirdiği Çözümler Konusunda Yerel Yöneticilerin Görüşleri”. İnönü Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 5 (8). Yolcu, H. and Kurul, N. (2009). “Evaluating the Finance of Primary Education in Turkey within the Context of Neo-Liberal Policies”. International Journal of Educational Policies, 3 (2), 24-45. Zimmer, R. W., Krop, C., Brewer, D. J., (2003). “Private Resources in Public Schools: Evidence from a Pilot Study”. Journal of Education Finance, 28, Spring, 485-522. Zoraloğlu, Y. R., Şahin, İ. and Fırat, N. S. (2004). “İlköğretim Okullarının Finansal Kaynak Bulmada Karşılaştıkları Güçlükler”. Eğitim Bilim Toplum, 2 (8), 4-17. 33