Sample TiC - WordPress.com

advertisement

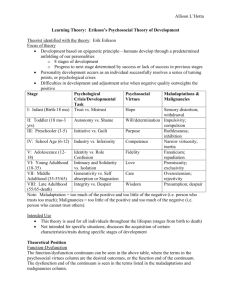

Joe Student April 27, 2012 Discovery and Exploration in a Time of Upheaval: Transitioning into Adulthood Taking a quarter off, dropping out, backpacking through the country, exploring the world, and discovering oneself. The present day generation of college-aged students is at a unique time in their life, one of uncertainty, yet full of hope for a perfect life in the future. New experiences are the norm and figuring out passions and interests, from love to work, is a subconscious priority. With a newly gained sense of independence, students are struggling to find out who they want to be and how to define themselves. At this point, many are trying to come to terms with whether this struggle, coined by some as a “quarterlife” crisis, really even exists. It is interesting to look at how modern day culture perpetuates the existence of this stage in life, and if it is not a mainstream idea at the present, perhaps it will be in the future. Moving past that, one has to ask, is this struggle a bad thing, or is it just a step that everyone will eventually take in life? Is this stage in life just a bridge to cross over the river dividing youth, adolescence, dependence, and naïveté from responsibility, stability, and being comfortable with oneself? We need to understand what exactly this stage in life is and how it should be defined. Different scholars believe that there are certain factors that accumulate to create the perfect opportunity for young adults to learn, experience, and find their place and role in society. Has this stage in life always existed, or has society and the younger generation itself slowly changed and created a more extended period of time where youth can explore and grapple with their identity. It is interesting to compare studies of youth in the in the 60’s and 70’s to the present day, in order to distinguish whether an early life crisis is a more recent trend. What are the implications of this trend, and what seems to have changed, in society, technology, or even culture, in order for a shift to a more apparent transition crisis? Identity crisis and formation and the transition into adulthood during human development seems to be so elusive and hard to package into a definitive idea and concept, leading to a variety of perspectives and different insight on the topic. What exactly is this stage, and how has it been explained in the past and the present? Has the idea changed as new stressors and different situations have arisen? Erik Erikson, a psychologist known for his work in the 1950’s, developed eight different stages of the life cycle. The fifth life cycle, which Erikson described in his book Identity Youth and Crisis, which occurs around the ages of 13 to 19 is entitled fidelity, with the issue centered on the conflict between identity and role confusion. When summarizing Erikson’s arguments in Introducing Erik Erikson: An invitation to his thinking, F. L. Gross writes that “Youth has a certain unique quality in a person's life; it is a bridge between childhood and adulthood…. great body changes accompanying puberty, the ability of the mind to search one's own intentions.” The possibility for the cause of an identity crisis could be due to the fact that youth are in a certain limbo, where they are not part of a well-defined defined state in life. Youth are tasked with coming to terms with themselves, and being comfortable with what they want to do, before they are able to transcend into adulthood. Erikson also came up with the term “identity crisis” and describes it in his book Identity and the Life Cycle. An identity crisis occurs if individuals are not able to come to terms with who they are, and thus experience a void and the inability to find themselves. Erikson’s ideas were formed in a different time period, so they may be outdated, because social structure and norms have changed somewhat drastically since then. Jeffrey Arnett, a professor in psychology at Clark University, has come up with a more recent idea and description of this stage of upheaval. He coins this stage as emerging adulthood, where he states, “becoming independent and self-sufficient is seen as the central issue” where the “central task is to move gradually toward making enduring commitments in love and work” (“Bridging” 266). Becoming independent seems to be a trend and a core struggle in the search to find an identity. With independence, Arnett seems to say, that discovering one’s identity is much more attainable. Arnett breaks up this stage into five separate classifications in Emerging Adulthood, which outline this life stage and describe some of the things individuals go through. The five stages are as follows: the age of identity explorations: people making crucial choices based on their own interests, the age of instability: frequent changes in turnover of jobs, love partners, and living arrangements, the self-focused age: independent decision making and few obligations, the age of feeling in-between: an age where individuals are neither teens nor adults, and the age of possibilities: high level of optimism and hope that life will eventually work out. This stage also goes through three different phases, beginning with the fact that relationships in which individuals’ felt dependant now turn towards relationships where the power is shared. This slowly allows for the movement into a stage where commitments to roles and relationships are temporary and transitory, where individuals can explore a series of commitments. Finally, the stage ends when people are able to make commitments and have found enduring roles and accept the responsibilities of adulthood. Arnett continues with outlining that the most important goals of this stage are dealing with friendship, academics, conduct, and work and romantic related commitments. Arnett creates a very well defined idea of this stage, because he is able to incorporate so many different aspects of what contributes to crisis and discovery. Is this even a real concept? Some researchers think not. Although this is a relatively new concept for scientific research, there has been some empirical data collected that supposedly points to a skeptical view of the stage that Arnett has created and defined in such detail. Nicole Rossi and Carolyn Mebert published an article in the Journal of Genetic Psychology outlining a statistical analysis of the well-being and happiness of high school, college, and graduate aged students. This study was done in response to a book written about the quarterlife crisis by Robbins and Wilner, and stated that there was “no empirical support was found for a quarterlife crisis particular to recent college graduates moving into the workforce” (153). The study comprised of multiple tests ranging from levels of depression to job satisfaction were evaluated. Interestingly, they do find that “high school graduates have a relatively more difficult time in multiple respects (i.e. social support from friends and family, depression, anxiety, life satisfaction, and future time perspective)” (153). These conclusions do definitely seem to fit with a lot of Arnett’s viewpoint, but seem to differ only in the magnitude that each views this moment in youths’ lives. Rossi and Mebert seem to see it as only a slight hiccup, not a long phase or stage that Arnett describes this struggle as. Is it possible that a something so complex and intricate, with so many factors contributing and influencing youth’s actions and though patterns can only be a slight bump or annoyance? Maybe, but it seems like a very strong statement to rule out that a quarterlife crisis doesn’t even exist. Even if studies say that the quarterlife crisis isn’t a true concept, does it even matter when culture and mainstream society perpetuates it? Eliza Thomas simply explains that it doesn’t necessarily matter whether or not this identity crisis in college-aged students, because society has embraced the concept, so it is relevant and important in today’s cultural conversation. Pop culture and the media has become one of the main outlets for information dissemination, and she realizes this writing: “Oprah dedicated a show to it, bloggers have ranted about it…. It even has its own shelf in the self-help section of the bookstore. There's no question that the "quarterlife crisis”…beyond a catchy phrase into a bona fide social trend” (Thomas). Does it matter that there are studies negating the fact that this crisis should even be a real concern? The media attempts to give the audience what it wants to hear, so it is quite possible that all of the attention that the quarterlife crisis has been getting is an accurate reflection of the sentiments felt by youth and even other generations. The previous statistical study could have been too narrow, or did not accurately represent what exactly a quarterlife crisis consists of. Has today’s generation of youth changed due to social and cultural factors, which has spurred the ever-increasing prominence of the quarterlife crisis? Kali Trzensniewski and M. Brent Donnellan write in their article “Rethinking ‘Generation Me’: A Study of Cohort Effects From 1976-2006” that many of the factors that youth have to deal with are indeed the same, and that they “found little evidence of meaningful change in egotism, self-enhancement, individualism, self-esteem, locus of control, hopelessness, happiness, life satisfaction.” If youth are acting the same and have to face the same pressures, has there been even been a change over the past 30 years. So most of the issues seem to be the same, but they do also state, “today’s youth have higher educational expectations than previous generations” (58). It could be possible that the pressures to go to college, especially at high-level institutions, are leading to an intensification of identity crisis and a need to find a meaningful and valuable place in life. Jeffrey Arnett wrote a response to this article in the Association for Psychological Science journal, where he reaffirmed “that the high-school seniors of 2006 are no different from the highschool seniors of 1976 on a wide range of variables, from self-esteem and life satisfaction to loneliness and antisocial behavior” (89). So why, then, is it just surfacing that a quarterlife crisis actually exists, if there aren’t many changes between youth today and in the past. Arnett argues that the change is: …not because high-school seniors in the early 21st century are much different from high-school seniors of the late 1970s, but because the period beyond high school really has changed dramatically over this time. Instead of entering adult roles of marriage, parenthood, and stable work shortly after high school, as most young people did in 1976, today most wait until at least their late 20s to make these transitions (90). The time period where individuals struggle with their identity and discover what they like seems to have shifted into a later age period. This is compared to the stage that Erikson outlined occurred during teenage years. The quarterlife crisis could be something that has always been around, but is only more apparent, because it is now at an age where people have historically been expected to have things already figured out. There is still a lot yet to be uncovered when dealing with this fascinating stage in life. In what ways are different groups, college students versus working youth, affected by this crisis? Is there a difference between the two, due to the different environment that each is in? Is this search for identity and a loss of place more apparent in elite colleges, because there is more of a pressure to be successful? It’s possible that this stage in life happens because of physical changes in brain structure, and this is the first point that most of the brain has fully matured, so environmental factors may not be and most likely is not the only thing influencing individuals’ growth. Now that I have a greater understanding of the academic perspective of the issue, it will be really helpful to get the perspective of actual students, and see if their feelings correspond with the data analyzed from more structured studies. What is really going on inside the head of those where braces and recess are a thing of the past, but an office job and filing taxes have yet to come? There certainly isn’t a definitive answer, but I hope to be able to uncover at least some of the intricacies of this stage in life. Works Cited Arnett, Jeffrey J. "Oh, Grow Up! Generational Grumbling and the New Life Stage of Emerging Adulthood—Commentary on Trzesniewski & Donnellan (2010)." Perspectives on Psychological Science 5.1 (2010): 89-92. Print. "Emerging Adulthood." Oxford University Press:. Ed. Jeffrey Arnett. Web. 27 Apr. 2012. <http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/Psychology/Developmental/?view=usa> . Erikson, Erik H. Identity and the Life Cycle. New York: Norton, 1980. Print. Erikson, Erik H. Identity, Youth, and Crisis. New York: W. W. Norton, 1968. Print. Furlong, Andy. Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood: New Perspectives and Agendas. London: Routledge, 2009. Print. Gross, F. L. (1987). Introducing Erik Erikson: An invitation to his thinking. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. p. 39. Kali H. Trzesniewski and M. Brent Donnellan. Rethinking “Generation Me”: A Study of Cohort Effects From 1976–2006. Perspectives on Psychological Science January 2010 5: 58-75, doi:10.1177/1745691609356789. Rossi, Nicole E., and Carolyn J. Mebert. "Does A Quarterlife Crisis Exist?." Journal Of Genetic Psychology 172.2 (2011): 141-161. Academic Search Premier. Web. 17 Apr. 2012. Thomas, E. (2004, Transcending the quarterlife crisis. Utne, (124), 71-72. http://search.proquest.com/docview/217434572?accountid=14026.