International Journal of Public Opinion Research

advertisement

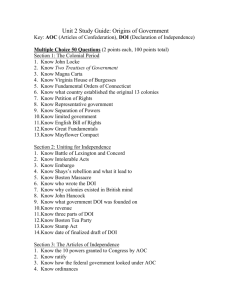

SSRC Eurasia Quantitative Methods Webinar Cultural Context and Measurement Validity in Comparative Survey Research Professor Jane Zavisca April 12, 2013 University of Arizona janez@u.arizona.edu Core dilemmas In comparing groups, want to be sure observed differences (or similarities) are substantive, not artifactual Simultaneous need for: Identities: universal measures with comparable meanings across contexts Equivalents: Particular measures that capture same concepts across contexts In cross-national surveys, often have identities – but are they equivalent? Bollen, Kenneth A., Barbara Entwisle, and Arthur S. Alderson. 1993. “Macrocomparative Research Methods.” Annual Review of Sociology 19 (January 1): 321–351. doi:10.2307/2083391. Przeworski, Adam, and Henry Teune. 1966. “Equivalence in Cross-National Research.” Public Opinion Quarterly 30 (4) (December 21): 551–568. doi:10.1086/267455. Heath, Anthony, Stephen Fisher, and Shawna Smith. 2005. “The Globalization of Public Opinion Research.” Annual Review of Political Science 8 (1): 297–333. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.8.090203.103000. Measurement equivalence Functional equivalence: concordance of meaning, of constructs as well as questions Measurement invariance: formal statistical equality of parameters in measurement models Sources of non-equivalence Errors of observation Substantive differences in meaning: linguistic, contextual Systematic differences in response styles: acquiescence bias, extreme response bias, social acceptability bias Errors of non-observation non-response bias Sampling approach Heath, Anthony, Jean Martin, and Thees Spreckelsen. 2009. “Cross-national Comparability of Survey Attitude Measures.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 21(3): 293–315. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edp034. Language example: happiness Poor linguistic equivalence English: “Are you a happy person?” Russian: ”Вы счастливый человек? / Вы счастливчик?» Could be interpreted as “Are you a lucky person?” О счастливчик! = name of “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire” reality show in Russian Better linguistic equivalence English: “Are you: very happy, pretty happy, not too happy, not happy at all.” Russian: Вы: очень счастливы, довольно счастливы, не очень счастливы, очень несчастны.» See: RUSSET Panel Survey: www.vanderveld.nl World Database of Happiness: http://www1.eur.nl/fsw/happiness/index.html Relationship between happiness & life satisfaction “Varies with the cultural and linguistic environment in which it is studied.” Constructs vs. questions: differences in meaning even with linguistic equivalence In Russian surveys Low correlations between general happiness and life satisfaction High correlation between general happiness and satisfaction with personal relationships; high correlation between life satisfaction and satisfaction with finances. Saris, Willem E., and Anna Andreenkova. 2001. “Following Changes in Living Conditions and Happiness in Post Communist Russia: The RUSSET Panel.” Journal of Happiness Studies 2: 95-109. Contextual difference: homeownership Conventional definition of homeowner: resident of “owner-occcupied household” Russia has highest rate of young homeownership (ages 21-35) in Western & Eastern Europe according to this definition (about 85%). But most are not living autonomously “Homeownership” Rates Ages 21-35, with and without extended family DETECTING MEASUREMENT NON-EQUIVALENCE USING MULTIPLE INDICATORS AND LATENT VARIABLE MODELS Limitations of single measures Impossible to statistically test whether observed difference (or similarity) is meaningful Example: consumer ethnocentrism Russians are more likely than Canadians to agree with the statement: “There should be very little trading or purchasing of goods from other countries unless out of necessity.” Possible sources of non-equivalence Translation Different interpretation, measuring different constructs Saffu, Kojo, and John Hugh Walker. 2005. “An Assessment of the Consumer Ethnocentric Scale (CETSCALE) in an Advanced and Transitional Country:The Case of Canada and Russia.” International Journal of Management 22 (4): 556-571. Latent variable approach Consumer ethnocentrism (National) products, first, last, foremost Foreign products only out of necessity Real (national) buys domestic Curbs should be put on all imports should always buy domestic Purchasing foreign is unpatriotic Foreigners should not be allowed to sell In latent variable model, oval represents latent construct, square represents manifest indicator. Buy domestic Keep country working Foreign should be heavily taxed Finding for Russia (National) products, first, last, foremost Consumer ethnocentris m Foreign products only out of necessity Real (national) buys domestic should always buy domestic Purchasing foreign is unpatriotic Buy domestic Keep country working cultural Economic Curbs should be put on all imports Foreigners should not be allowed to sell Foreign should be heavily taxed Example: National Identity Defined as beliefs about importance of potential determinants of membership of the nation. Theory suggests 2 dimensions Civic: residence, citizenship, respect for law/institutions Ethnic/ascriptive: birthplace, descent, religion Common example in methodological literature Davidov, Eldad. 2009. “Measurement Equivalence of Nationalism and Constructive Patriotism in the ISSP: 34 Countries in a Comparative Perspective.” Political Analysis 17 (1) (December 21): 64–82. doi:10.1093/pan/mpn014. Heath, Anthony, Jean Martin, and Thees Spreckelsen. 2009. “Cross-national Comparability of Survey Attitude Measures.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 21 (3) (September 21): 293–315. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edp034. Loner, Enzo, and Pierangelo Peri. 2009. “Ethnic Identification in the Former Soviet Union: Hypotheses and Analyses.” Europe-Asia Studies 61 (8): 1341–1370. doi:10.1080/09668130903134798. Kunovich, Robert M. 2009. “The Sources and Consequences of National Identification.” American Sociological Review 74 (4) (August 1): 573–593. doi:10.1177/000312240907400404. Sarrasin, Oriane, Eva G. T. Green, André Berchtold, and Eldad Davidov. 2012. “Measurement Equivalence Across Subnational Groups: An Analysis of the Conception of Nationhood in Switzerland.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research (October 18). doi:10.1093/ijpor/eds033. Measurement model for pooled ISSP data Civic Citizenship Respect laws Born in nation Speak language Life-long resident Ethnic Source: Heath 2009 Feel nat’l identity Nat’l ancestry Nat’l religion Citizenship as ethnic Countries where citizenship rules restrictive, ascriptive Countries that are ethnically homogenous Includes most former Soviet countries, Austria, Switzerland Source: Heath 2009 Citizenship as civic Countries where citizenship rules less restrictive Countries with historical ethnic diversity Includes Czech Republic, Spain, Australia, Israel Source: Heath 2009 Formal tests for measurement invariance Configural invariance (weak): factor structure equivalent (same items load on same latent variables) Metric invariance (strong): factor loadings equivalent: necessary to compare relationships between constructs (e.g. regression coefficients). Scale invariance (strict): factor loadings and intercepts equivalent; necessary to compare means Partial invariance: at least two items load equally on each construct. Byrne, Barbara M., and Fons J. R. van de Vijver. 2010. “Testing for Measurement and Structural Equivalence in Large-Scale Cross-Cultural Studies: Addressing the Issue of Nonequivalence.” International Journal of Testing 10 (2): 107–132. doi:10.1080/15305051003637306. Cheung, Gordon W. 2008. “Testing Equivalence in the Structure, Means, and Variances of Higher-Order Constructs With Structural Equation Modeling.” Organizational Research Methods 11 (3) (July 1): 593–613. doi:10.1177/1094428106298973. Steenkamp, Jan‐Benedict E. M., and Hans Baumgartner. 1998. “Assessing Measurement Invariance in Cross‐National Consumer Research.” Journal of Consumer Research 25 (1) (June 1): 78–107. doi:10.1086/209528. What to do when invariance not achieved Delete problematic groups or countries from comparison set Delete problematic items from measurement model Settle for partial invariance: configural invariance, plus at least 2 indicators per latent variable with equal loadings and/or intercepts Problem with formal tests of invariance Formal strictness can undermine substance “Just as cross-national researchers recognize that indicators may need non-literal translation to maximize the comparability between countries, constructs also may need non-literal translation.” (Medina et al 2009) Achieving functional equivalence Statistical approaches “Locally-conditioned models”: control for reasons for invariance (Medina 2009) Introduce contextual predictor variables – i.e. directly model cross-group differences (Davidov 2012) Qualitative context Investigate sources of invariance through cognitive interviews, observation (Carnaghan 2011) Davidov, Eldad, et al. 2012. “Using a Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling Approach to Explain Cross-Cultural Measurement Noninvariance.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 43 (4): 558–575. doi:10.1177/0022022112438397. Carnaghan, Ellen. 2011. “The Difficulty of Measuring Support for Democracy in a Changing Society: Evidence from Russia.” Democratization 18 (3): 682–706. doi:10.1080/13510347.2011.563113. RESPONSE STYLE BIAS Response styles Tendencies in responses, independent of true belief. Types of response styles Tendency to agree (acquiescence bias) Tendency to moderate responses Tendency to extreme responses Create bias in likert scales (e.g. agree-disagree), yes/no questions Problematic when tendency to acquiesce varies across groups to be compared Harzing, Anne-Wil. 2006. “Response Styles in Cross-national Survey Research A 26-country Study.” International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 6 (2) (August 1): 243–266. doi:10.1177/1470595806066332. Kieruj, Natalia D., and Guy Moors. 2013. “Response Style Behavior: Question Format Dependent or Personal Style?” Quality & Quantity 47 (1) (January 1): 193–211. doi:10.1007/s11135-011-9511-4. Tobi, Hilde, and Jarl K. Kampen. 2013. “Survey Error in an International Context: An Empirical Assessment of Cross-cultural Differences Regarding Scale Effects.” Quality & Quantity 47 (1) (January 1): 553–559. doi:10.1007/s11135-011-9476-3. Example: acquiescence in Kazakhstan Survey experiments on tendency to agree among Kazakh vs. Russian respondents in Kazakhstan Javeline, Debra. 1999. “Response Effects in Polite Cultures: A Test of Acquiescence in Kazakhstan.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 63 (1) (April 1): 1–28. doi:10.2307/2991267. Possible causes of acquiescence bias Cultural significance of hospitality, deference, avoiding offense Uncertainty about answer; assume statements contain cues about correct answer Cognitive burden Must infer counterarguments If agree with inferred counterargument, must disagree with statement (yes/no) Satisficing due to fatigue, disinterest Example: freedom versus order Version A: “People should be free to say whatever they want, even if what they say increases tensions in society.” Version B: “Public order should be maintained above all, even if it requires limiting freedom of speech.” Version C: “Certain people think that it is better to live in a society with strict order, even if it requires limiting freedom of speech. Others think that people should be free to say whatever they want, even if what they say increases tensions in society. Which view is closer to your own? Do you feel this way strongly or only somewhat?” Response options for versions A & B are: strongly agree/ somewhat agree/ somewhat disagree/ strongly disagree Version C is a “forced choice” format question Evidence for acquiescence bias 45 40 35 30 25 A: pro-freedom B: pro-order 20 C: forced choice 15 10 5 0 freedom -- very freedom -- somewhat order -- somewhat order -- very In absence of bias, proportions should be the same for all 3 versions. Acquiescence bias overstates support for freedom in version A, understates support for freedom in version B. Comparison of Kazakhs & Russians VERSION A VERSION B 45 45 40 40 35 35 30 30 25 25 20 20 Kazakh 15 15 Russian 10 10 5 5 0 0 freedom -very freedom -somewhat order -somewhat order -- very freedom -very freedom -somewhat order -somewhat order -- very VERSION C 40 35 30 25 20 Kazakh 15 Russian 10 5 0 freedom -very freedom -somewhat order -somewhat order -- very CONCLUSION: Acquiescence bias in Version A understates differences Between groups What to do Avoid likert scales (esp agree/disagree) Use forced choice formats If using likert scale: Randomize direction of question