Professional Development - Millersville University

advertisement

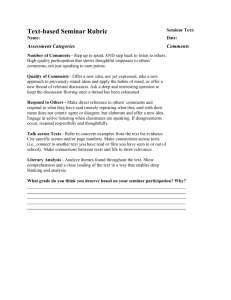

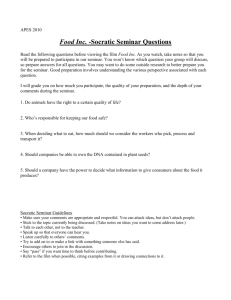

FYI Seminars Overview of Workshop Segment 1: Choosing a Topic/Organizing the Course Segment 2: Seminar Format/Readings LUNCH Segment 3: Service Learning/Civic Engagement Segment 4: Writing Assignments & Assessments Review of the Day Choosing a Topic/Organizing the Course FYI Seminar Planning Worksheet Step 1: Questions and Controversies What are the major questions and controversies in your discipline/topic? Question/Controversy 1 Question/Controversy 2 Question/Controversy 3 Question/Controversy 4 FYI Seminar Planning Worksheet Step 2: History of Questions/Controversies What is the history of those questions and controversies? 1. Origins of Controversy 3. Important Contributors 2. Paradigm Shifts 4. Current Status FYI Seminar Planning Worksheet Step 3: “Big Questions” Who cares? Why are these questions/controversies important and worth study? 1. What first interested you in your own studies? 3. Philosophical/ethical implications? 2. Broader implications for knowledge of world? 4. Contribution to human/social progress? Relevance to students? Beloit Mindset List (http://www.beloit.edu/mindset/) Richard Light, Making the Most of College: Students value classes that make them “a slightly different person” (p. 47) Tim Clydesdale, The First Year Out Popular Seminar Topics at TCNJ 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. This is Your Life on Music Mortality, Mind, and the Meaning of Life Popular Culture, Power, and Identity Advertising & Society: The Good, the Bad, & the Ugly Multicultural New York Friends Forever: Examining Online Socializing Making Sense of Life, For Life The Beatles and Their World The Cultural Phenomenon of Harry Potter Being Me, Knowing You: The Foundations for Human Encounter Unpopular Seminar Topics at TCNJ Protecting New Jersey's Pinelands Africa and the West: From Monologue to Dialogue Our Town and Other Works by Thornton Wilder The Geology and Tectonics of Africa Strong Democracy and Student Leadership The Worlds of Moby-Dick Harlem Renaissance: Black Paris The Evolution of African American Gospel Music Race, Ethnicity, Class and Gender in the Anglophone Caribbean 10. Concert Dance of the 20th Century in America 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. FYI Seminar Planning Worksheet Step 4: Relevance to Students How might my seminar’s questions/controversies intersect students’ lives? 1. Fun facts to know & tell 3. Personal stories 2. Topical relevance to pop culture 4. The unexpected and mysterious Putting Everything Together Which items or boxes from Steps 1-4 seem to go together? Try to link up at least one item or box from each sheet (especially Steps 2-4) into one “unit” for a prospective FYI Seminar. Try to come up with at least three or four “units” in this way. How might these “units” accomplish the course objectives of the FYI Seminars? FYI Seminar Course Objectives Investigate a specific topic or question in-depth. Consider the connections within and between various fields of study. Discuss and explore how diverse viewpoints can aid and enhance research and understanding. Recognize the need to explore underlying assumptions in both people and text. Demonstrate strengthened inquiry, research and information literacy skills. Reflect upon the importance of civic responsibility. Discuss and practice integrity within personal and educational contexts. Develop skills in oral discussion and written communication. Learn to utilize University resources. Seminar Format/Readings Seminar Format: What We Just Did Small, well-defined tasks that built toward a specific, planned outcome, relevant to the participants’ needs and interests. Small, in-class writing exercises to prime participants for discussion. Paired discussion and group work. Reporting out. Large-group fact-gathering, brainstorming, and discussion. Even a little lecturing. Seminar Format: Questions to Consider In a free-wheeling discussion, how will students know what to write down in their notes? Which is better – debate or consensus-building? How can I tell if class is going well (or badly)? What happens when the discussion gets sidetracked? Should I call on people or only on volunteers (and what if the same two people are always the only volunteers)? Should I grade participation? What are reasonable expectations for how much one class meeting can cover? Seminar Format: Goals to Strive For Lecture less. Teach students to think like a . . . (sociologist, physicist, artist, journalist, teacher). Encourage students to take responsibility for their own education and to take an active part in it. Help students to retain what they learn in class. Allow students to experiment with ideas and deepen their understanding of material. Give students the opportunity to learn by teaching their peers. FYI Seminar Planning Worksheet Step 5: Readings What should the students read? 1. Texts that provide essential background 3. Provocative, troubling, polemical, cutting-edge texts 2. Milestones in history of questions/controversies 4. Texts with which I vehemently disagree Reasonable Expectations: Student Responsibility for Reading Expect and encourage maturity/commitment…. But remember what high school is like (meeting every day, busy work, etc.) and help students to be responsible without your looking like a police officer. Easy, low-stress, not-gotcha quizzes Response papers (short, informal responses to readings submitted at the beginning of class – once a week, on assigned days, or student’s choice) Collected in-class writing Opening or closing statements (one-minute précis of thoughts about the reading from each student, going around the room at the beginning or end of class) Reasonable Expectations for Student Reading Quantity of reading to be assigned For each text, time yourself and multiply by two to get student reading speed for that text. Expect students to work two hours outside of class for every hour in. Quality of reading on students’ parts Be happy about whatever level of comprehension the students achieve. Model good reading strategies in class for each type of reading before expecting students to read those types with sophistication. FYI Seminar Planning Worksheet Step 6: Teaching Reading Strategies How do you read? Where do you start? How do you proceed? 1. Texts that provide essential background 3. Provocative, troubling, polemical, cutting-edge texts 2. Milestones in history of questions/controversies 4. Texts with which I vehemently disagree Writing Assignments & Assessments Writing Assignment Gimmicks Writing for audiences other than the professor Make-believe audiences (e.g., composing a position paper for the Obama transition team) “Real” audiences (e.g., drawing up a feasibility study for an ice cream shop on campus to be submitted for real to the College President’s office) Internet audiences (e.g., keeping a blog, open to anyone and everyone on the web) Peer audiences (e.g., submitting papers not only to professor but to classmates OR “publishing” papers in a collection of class essays) A Good Writing Assignment... Gives a brief and clear description of exactly what students are supposed to do and how their work will be evaluated. Asks students to do something very specific while also allowing them to follow their own interests and ideas. Builds on what students have been doing in class but goes further in some way. Provides ample opportunity for students to practice and show off specific skills and concepts that they have learned. Promises to be interesting for the professor to read. Doesn’t stand alone as the only communication about the paper. Informal Write-to-Learn Assignments In-class writing Response papers Blogs Threaded discussion boards Posters Search-and-destroy research assignments Sample Grading Rubric A = Outstanding An "A" paper has a strong, clear, interesting, narrow, and specific thesis and an introduction that provides an interesting, helpful preview of the content, logic, and organization of the paper. An "A" paper provides relevant, concrete evidence and logically persuasive reasons for every assertion. An "A" paper has a clear and consistent overall organization that relates all the ideas of the paper together logically in a thoughtful, sophisticated, and memorable manner with ample transitions to aid the reader. An "A" paper has unified, coherent, and well-developed paragraphs without exception. An "A" paper has almost no errors of grammar, punctuation, word choice, or usage. The writer consistently uses sentences that are clear, concise, effective, and varied in terms of length and structure. An "A" paper synthesizes the information and arguments from multiple, reliable sources into its own argument, summarizing its sources fairly and assessing them critically. B = Good A "B" paper has a strong, clear, interesting, narrow, and specific thesis, but the introduction is not a wholly adequate preface to the content, logic, and organization of the paper. A "B" paper provides relevant, concrete evidence and logically persuasive reasons for most assertions. A "B" paper has a clear and consistent overall organization that relates all the ideas of the paper together logically with transitions for the reader at significant points in the paper. A "B" paper has unified, coherent, and well-developed paragraphs for the most part. A "B" paper has some errors of grammar, punctuation, word choice, or usage. The writing is always clear, although it is not always concise, effective, and varied. A "B" paper uses multiple, reliable sources, but uses them merely to provide specific evidence for its own argument. C = Adequate A "C" paper has a clear thesis, but the thesis is vague, broad, uninteresting, or not wholly relevant to the assignment. A "C" paper provides evidence and reasons for most assertions, but the evidence and reasons are frequently not the most relevant or the most logically persuasive or the most thoroughly developed. A "C" paper has a clear and consistent overall organization, but the organizational principle is vague, uninteresting, or inadequate. Transitions tend to be weak, uninspired, or vague. A "C" paper has significant problems with the unity, coherence, or development of some of its paragraphs. A "C" paper has a number of errors of grammar, punctuation, word choice, and usage, but the writing remains comprehensible at all times. The sentences are sometimes short and choppy or long and wordy. A "C" paper uses evidence from a source of questionable reliability uncritically or relies too heavily on a single source at key moments in its argument. D = Deficient A "D" paper has a thesis, but the thesis is unclear and vague. A "D" paper rarely provides real evidence or real reasons for its assertions. The paper is made up mostly of unsubstantiated opinion. A "D" paper does not have one clear organizational principle or does not follow through on its initial organizational principle consistently. A "D" paper has frequent problems with the unity, coherence, or development of its paragraphs. A "D" paper has many errors of grammar, punctuation, word choice, and usage, and the writing is sometimes incomprehensible with little variation in terms of sentence length and structure. A "D" paper relies heavily on unreliable sources or seriously misrepresents its sources. FYI Seminar Planning Worksheet Final Step of the Day: Criteria for Evaluating Writing What matters most in student writing? What makes good and bad writing? 1. 2. “A” writing: “A” writing: “B” writing: “B” writing: “C” writing: “C” writing: “D” writing: “D” writing: 3. 4. “A” writing: “A” writing: “B” writing: “B” writing: “C” writing: “C” writing: “D” writing: “D” writing: What obstacles or questions remain? Resources Ken Bain, What the Best College Teachers Do (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2004), ISBN 0674013255 Tim Clydesdale, The First Year Out (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007), ISBN 0226110660 James M. Lang, On Course (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2008), ISBN 0674028067 Richard J. Light, Making the Most of College (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2004), ISBN 067401359X