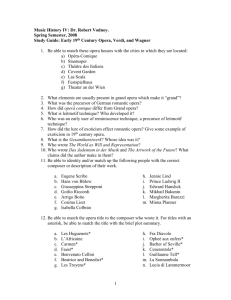

this document

advertisement

Honorary President: The Duchess of Buccleuch & Queensberry Dumfries Choral Society gratefully acknowledges the generous financial assistance which has been given for the 2013-14 season by those Patrons, Friends and Sponsors listed below. The Society was sorry to hear of the death of former Patron Mrs Jean Ferguson, who for many years sang as a soprano with Dumfries Choral Society before becoming a very generous and supportive Patron. We were also sorry to hear of the death of Mrs Mary Halliday, one of our ‘Friends’ and a long-time Choral supporter. Patrons Friends The Duchess of Buccleuch Mrs Margaret Carruthers Mr Peter Duncan Mr & Mrs Tom Florey Mr & Mrs Kenneth Kelly Miss Gerry Lynch MBE Mr J & Dr P McFadden Mrs Agnes Riley Mr & Mrs Peter Boreham Mrs Jessie Carnochan Mrs Mary Cleland Mrs Maureen Dawson Mrs Agatha Ann Graves Mrs Margaret Forsyth Mr David Kellar Mr A Hamish MacKenzie Mrs Jean Mason Mr Ian P.M. Meldrum Mr & Mrs James More Mr Hugh Norman Mr & Mrs Frank Troup Mr John Walker Mrs Maxine Windsor Sponsors Asher Associates Barbours, Dumfries Barnhill Joinery Ltd Cavens Elite Display The Aberdour Hotel If you would like information about becoming a Friend, Patron or Sponsor, please contact the Patrons’ Secretary, Dr Brian Power (01387 262543) or visit the Society’s web site: www.dumfrieschoralsociety.org.uk Programme 1813 – 1901 Stabat Mater Giuseppe VERDI Bridal Chorus Richard WAGNER 1813 - 1883 Matthew Todd Tenor: Ah La Paterno Mano (Macduff's Aria) From Verdi's Macbeth Pilgrims Chorus Wagner Brindisi VERDI ~ Interval ~ Procession & Chorale Richard WAGNER 1813 - 1883 Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves Giuseppe VERDI 1813 – 1901 Dorothy King Soprano: Träume from Wesendonck Lieder Wagner Spinning Chorus WAGNER Te Deum VERDI Conductor: Nick Riley Organist: John Morris Accompanist: Margaret Harvie Please note that use of any form of unauthorised photographic or recording equipment during the performance is expressly forbidden. You are also politely requested to ensure that all mobile phones, pagers, watch alarms, etc are disabled before the start of the performance. Dorothy King Dorothy is a native of Dumfries and Galloway and studied at the RSAMD in Glasgow gaining degrees in Music Education and Singing Performing before going on to study at the Opera School there performing roles such as Marcellina in The Marriage of Figaro and Florence in Albert Herring by Benjamin Britten. She joined Scottish Opera in 1995 and performed many roles and covers including Annina in La Traviata, Inez in Il Trovatore and The Foresters Wife in Cunning Little Vixen by Janacek. During her time with Scottish Opera she performed the role of Verdi’s Lady MacBeth with Edinburgh Grand Opera and Santuzza from Cavalleria Rusticana for The Singers Company. She also sang excerpts from Wagner’s Operas for Opera on a Shoestring. She subsequently was granted a year’s sabbatical to study with Linda Esther Gray in London to enable her to work on Dramatic Soprano repertoire hence her great love of Verdi and Wagner. She has also performed the role of Tosca for European Chamber Opera. During her musical career she has performed with music societies and choirs in her home area and in the North of England. Dorothy has combined her singing with a teaching career, both in schools and privately at her home. She presently teaches Singing and Piano from her music studio whilst being involved with local music making. Matthew Todd A graduate of the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Matthew is a passionate performer with a vast and varied repertoire. He has performed many operas and song-cycles and recently sang the title role in Elgar's Dream of Gerontius. A former Choral Scholar of Paisley Abbey, he now directs several choirs in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Helensburgh. He is also a dedicated singing teacher and a passionate Community Musician. He provides music for adults with complex needs and ran a therapy programme for disabled orphans in Lugoj, Romania last summer. In addition to music, Matthew is a keen writer with a fascination for history. Last year saw the launch of his historical novel 'For the King' and the premier performance of his Choral Drama 'Such is the Kingdom' in Glasgow Cathedral. John Morris (Organist) John Morris trained at the Royal College of Music under Douglas Guest, Herbert Sumsion, Harry Platts and Millicent Silver. He is a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists, a Graduate of the Royal Schools of Music, an Associate of the Royal College of Music and has played in venues as diverse as St Paul’s Cathedral and HMP Liverpool (as a guest of the Chaplaincy). John has performed in this country and abroad, broadcast on the BBC and has played for over 300 choral services in Carlisle Cathedral as well as performing in major events at St Bees School for the last two decades. He is also Production Manager of The London Organ Concerts Guide. In his spare time, John enjoys playing Jazz with his wife, Lisa, gardening and chandlery. Margaret Harvie (Rehearsal accompanist, Dumfries Choral Society) Margaret was a pupil of Mary Moore in Edinburgh and also a member of the Edinburgh University Singers under the direction of Herrick Bunney. A well known Dumfries musician, she has been accompanist of Dumfries Male Voice Choir and is a former official accompanist to the Dumfries and District Competitive Music Festival. She is organist of Irongray Church. As accompanist to the Dumfries and Galloway Chorus and in a similar role with the former Dumfries and Galloway Arts Festival Chorus, Margaret has worked, to acclaim, with internationally known conductors including Christopher Seaman, Philip Ledger, Owain Arwel Hughes, Takua Yuassa and Christopher Bell. In March 1996, Margaret was honoured by Dumfries and Galloway Regional Council with an Artistic Achievement Award in recognition of the very great contribution she makes to the artistic life of our community as an accompanist and last November at Dumfries and Galloway Life People of the Year 2012 Award Ceremony, Margaret, a culture champion nominee, was presented with a Special Award comendat8ion for her services to music. Margaret has been accompanist to Dumfries Choral Society since 1975. Nick Riley Nick Riley started his early musical education with his father Arthur (piano) and John Burnett (flute). Within a few years he was to become a junior student in the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama before going on to study music full time at Glasgow University and Aberdeen College of Education. Returning to Dumfries and Galloway in 1985 Nick took up a teaching post in Stranraer Academy. During this time he learned of a performance of Bach’s B Minor Mass being performed by Dumfries Choral Society, a work he had always wished to perform: Nick joined the choir for the performance, which marked the beginning of an enjoyable and fruitful period with the Society. Nick was to later become the choir’s principal conductor from 1989 to 1996. Nick has been involved with local music making in many capacities: as a teacher of flute and piano, as conductor of the Dalgarno Singers, and as musical director of many shows for the (now) Dumfries Musical Theatre Company. He is also a founder member of the Solway Sinfonia, in which he plays principal flute and is the current Chairman. Nick also continues to play with jazz group Baroque and Blue, a group founded with friends in 1983. Nick teaches music and is a Faculty Head in Wallace Hall Academy, where he has taught since 1990. Richard Wagner (1813-1883) and Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) It is arguable which of two years in the history of western music were the more significant – 1685, which saw the births of Bach and Handel (not forgetting Scarlatti!), or 1813, which saw the births of Verdi and Wagner (not forgetting Alkan and Dargomizhsky!). In general musical terms, Bach probably had the greatest overall influence, but in the more restricted field of opera the importance of 1813 to the development of this particular artistic form is unchallengeable, and it is therefore entirely appropriate that the bicentenary of the births of the two masters Richard Wagner (the elder by some 4½ months) and Giuseppe Verdi is being so widely celebrated this year. Space does not permit any detailed coverage of their lives and work, and any attempt to try and stake any claim as to which was the greater is rather pointless. They followed remarkably similar careers in that neither ventured significantly off their preferred musical path, although Verdi’s contribution to the field of choral music cannot be overrated. Both brought astonishing dramatic and compositional skills to their operatic endeavours, but applied them in different ways: the Teutonic Wagner sought an ordered intellectual totality through a seamless integration of text, music, and setting (manifested in the creation of his own theatre at Bayreuth), while the Mediterranean Verdi sought to give opera greater dramatic expression by bringing passion and psychology to his characterization. Both were revolutionary, and the continuing popularity of what is regarded, rightly or wrongly, as something of an elitist art form, is eloquent tribute to their extraordinary achievement. Giuseppe Verdi: Stabat Mater [No.2 of Quattro pezzi sacri] [Choir and organ] Verdi produced his last opera Falstaff, based on Shakespeare, in 1893 at the age of eighty. Following its great success his librettist Boito suggested ideas for versions of both Antony and Cleopatra and King Lear to the composer, but, alert to the handicap of his advancing years, Verdi saw the effort of writing another large work for the stage as too much for him, and instead he turned his attention to purely choral music. Twenty years earlier he had composed his formidable setting of the Requiem, and in the intensity and conviction of this work he showed his mastery of writing sacred music, albeit in something of a radical style. A few years later he produced brief settings of the Ave Maria and the Pater noster, and then in 1889 another four-part unaccompanied Ave Maria, this time based on an ‘enigmatic scale’ which appeared as a puzzle in the Gazzetta Musicale. In between work on his last two great operas Otello and Falstaff he composed the serene and tender Laudi alla Vergine Maria for unaccompanied four-part female chorus, and finally brought his writing career to a close between 1895 and 1897 with large-scale settings of the Stabat Mater and the Te Deum. These four pieces were grouped together and published by Ricordi in 1898 as the Quattro Pezzi Sacri [Four Sacred Pieces]; although they frequently are, Verdi never actually intended that they should necessarily be performed complete, and to begin with he allowed only the first three to be given together. The text of the Stabat Mater, a late mediaeval sequence about the Virgin Mary’s grief-stricken vigil at the foot of the cross, with authorship attributed to the Franciscan Jacopone da Todi, was readmitted to the Catholic liturgy in 1727, though it was used widely in private devotions before then. It has been widely set to music, almost exclusively for non-liturgical purposes, and it is interesting to note the variations in length of some of these settings, ranging from approximately 20-30 minutes (Vivaldi, Szymanowski, Domenico Scarlatti), to 30-45 minutes (Poulenc, Pergolesi, Cecilia McDowall, Schubert), to 45-60 minutes (Rossini, Howells, Stanford), to Dvořák’s monumental 90 minute version. And the shortest of them all? – Palestrina’s and Verdi’s, both coming in at around 12 minutes. In Verdi’s case particularly, however, brief does not mean less – the orchestral requirements (replaced this evening by the organ) in both the Stabat Mater and the Te Deum are greater than those of his earlier Requiem and of almost all those other composers’ versions mentioned! But the most striking feature of Verdi’s Stabat Mater in comparison to other settings is its intensity; as with the Te Deum he sets the text completely straightforwardly, without repetition, thereby nodding respectfully towards Palestrina who had adopted precisely the same approach 400 years earlier. Four solemn repeated chords lead directly into a huge heart-rending outburst from the choir which instantly captures the mood of the text to perfection. Having caught that mood, Verdi drives it forward with a relentless momentum, responding to the subtleties of the poem through huge dynamic contrasts and the alternating of colossal block choral sections with plangent, melodic single vocal lines. Like no other he brings the text to life with all the skill he applied to his operatic libretti, demonstrating that as a word-setter he was in a league of his own dramatically. Stabat mater dolorosa juxta Crucem lacrymosa dum pendebat Filius. Cujus animam gementem contristatam et dolentem pertransivit gladius. O quam tristis et afflicta fuit illa benedicta Mater unigeniti! Quae moerebat et dolebat, pia mater, dum videbat nati peonas inclyti. Quis est homo, qui non fleret, Matrem Christi si videret in tanto supplicio? Quis non posset contristari, Christi matrem contemplari dolenten cum Filio? Pro peccatis suae gentis vidit Jesum in tormentis et flagellis subditum, Vidit suum dulcem natum moriendo desolatum, dum emisit spiritum. Eja Mater, fons amoris! Me sentire vim doloris fac, ut tecum lugeam. A weeping mother stood full of sorrow beside the cross as her Son hung there. Through her grieving heart, anguished and lamenting, a sword had passed. Oh, how sad and afflicted was that blessed Mother of an only Son! She mourned and grieved and trembled as she saw the suffering of her glorious Son. Who is the man who would not weep, seeing the mother of Christ in such torment? Who would not feel compassion, watching the mother of Christ sorrowing for her Son? She saw Jesus in torments and subjected to scourging for the sins of his people. She saw her dear Son dying forsaken, as he yielded up his spirit. O Mother, fount of love, make me feel the strength of your grief so that I may mourn with you. Fac ut ardeat cor meum in amando Christum Deum, ut sibi complaceam. Sancta mater, istud agas, crucifixi fige plagas cordi meo valide. Tui nati vulnerati, tam dignati pro me pati, poenas mecum divide. Fac me tecum pie flere, crucifixo condolere donec ego vixero. Juxta crucem tecum stare, et me tibi sociare in planctu desidero. Virgo virginum praeclara, mihi jam non sis amara, fac me tecum plangere. Fac, ut portem Christi mortem, passionis fac consortem, et plagas recolere, Fac me plagis vulnerari, fac me cruce inebriari, et cruore Filii. Flammis ne urar succensus, per te, Virgo, sim defensus, in die judicii. Christe, cum sit hinc exire, da per matrem me venire ad palmam victoriae. Quando corpus morietur, Fac, ut animae donetur Paradisi Gloria. Amen. Make my heart burn with love for Christ, my God, so that I may please Him. Holy Mother, do this for me: fix the wounds of your crucified Son deeply in my heart. Share with me the pains of your wounded Son who deigned to suffer for me. Make me weep with you and share the agony of the crucified, as long as I live. I long to stand with you beside the cross and join you willingly in your weeping. O Virgin, peerless among virgins, do not be harsh towards me, let me weep with you. Grant that I may bear Christ’s death and recall to my mind his fated passion and his wounds. Grant that I may be wounded by his wound, intoxicated by his cross, for love of your Son. Be close to me, o Virgin, lest in flames I burn and die, in his awful day of judgement. Christ, when you call me from this world, may your Mother be my defence, your cross my victory. When my body dies, let my soul be granted the glory of Heaven. Amen. Richard Wagner: Bridal chorus (from Lohengrin) [Choir and piano] First performed in 1850, Lohengrin is set in mediaeval Antwerp; it deals with the settling of a dispute over the succession to a dukedom, which results in one of the claimants, Elsa von Brabant, being promised in marriage to a mysterious knight as his reward for championing her cause, the only condition being that she must never ask him his true name or origin. As the wedding celebrations begin in Act III, Elsa and her groom are escorted into the bridal chamber to the sound of this chorus, which has found lasting popular success in its use at many a marriage ceremony. Unfortunately Elsa cannot restrain herself from forcing Lohengrin to reveal his identity as the son of Parsifal; he returns to the temple of the Holy Grail, carried off in a boat drawn by a swan which is transformed into Elsa’s murdered brother, who is miraculously brought back to life and proclaimed by the departing Lohengrin as the new Duke of Brabant as Elsa falls lifeless to the ground. Treulich geführt ziehet dahin, wo euch der Segen der Liebe bewahr’! Siegreicher Mut, Minnegewinn eint euch in Treue zum seligsten Paar. Streiter der Tugend, schreite voran! Zierde der Jugend, schreite voran! Rauschen des Festes seid nun entronnen, Wonne des Herzens sei euch gewonnen! Duftender Raum, zur Liebe geschmückt, nehm’ euch nun auf, dem Glanze entrückt. Treulich geführt, &c. Faithfully guided, come to this place where the blessing of love shall enfold you! Love, the reward of courage triumphant, truly makes you a most happy pair. Champion of virtue, proudly advance! Flower of youth, gracefully advance! Having escaped from the feast’s merriment, now may your hearts be filled with bliss! The fragrant room, bedecked for love, Shall now enclose you, far from the light. Faithfully guided, &c. Wie Gott euch selig weihte, zu Freuden weihn euch wir; in Liebesglücks Geleite denkt lang der Stunde hier! God blessed you with happiness, we wish you lasting joy; favoured by love’s fortune long remember this hour! Treulich bewacht bleibet zurück, wo euch der Segen der Liebe bewahr’! Siegreicher Mut, Minne und Glück eint euch in Treue zum seligsten Paar. Streiter der Tugend, bleibe daheim! Zierde der Jugend, bleibe daheim! Rauschen des Festes seid nun entronnen, Wonne des Herzens sei euch gewonnen! Duftender Raum, zur Liebe geschmückt, nehm’ euch nun auf, dem Glanze entrückt. Treulich bewacht, &c. Faithfully guarded, stay behind where the blessing of love shall enfold you! Courage triumphant, love and fortune truly make you a most happy pair. Champion of virtue, stay within! Flower of youth, stay within! Having escaped from the feast’s merriment now may your hearts be filled with bliss! The fragrant room, bedecked for love, has now enclosed you, far from the light. Faithfully guarded, &c. Giuseppe Verdi: Ah, la paterna mano [Macduff’s aria] (from Macbeth) [Tenor and piano] Verdi’s first Shakespeare adaptation was initially staged at Florence in 1847, but then underwent a series of changes and revisions for a performance in Paris in 1865. The libretto by Francesco Maria Piave failed to portray the complexity of Shakespeare’s characters and is generally considered somewhat weak dramatically, but musically Verdi had taken a big step forward, and Macbeth is now regarded as one of his most expressive and forceful operas. The tyrant Macbeth has killed Macduff's children and his wife, and in the first scene of Act IV Macduff (a tenor role), immensely saddened by this news, laments the loss of his family, and is determined to avenge their deaths, which he accomplishes at the end of the opera. O figli, o figlio miei! Da quel tiranno tutti uccisi voi foste, e insiem con voi la madre sventurata! Ah, fra gli artigli di quel tigre io lasciai la madre e i figli? Ah, sons, my dear sons! You all were killed by that tyrant, and, together with you, your unhappy mother too! Ah! I let into the claws of that tiger the mother and her sons! Ah, la paterna mano non vi fu scudo, o cari, dai perfidi sicari che a morte vi ferîr! E me fuggiasco, occulto voi chiamavate invano coll'ultimo singulto, coll'ultio respir. Ah! trammi al tiranno in faccia, Signore, e s'ei mi sfugge possa a colui le braccia del tuo perdono aprir. Ah! The paternal hand didn't defend you, my dears, from the hired ruffians that wounded you to death! And you looked in vain for me, a concealed fugitive, with your last sobs, with your last sighs. Ah! Bring me in front of that tyrant, Lord, and if he escapes from me may I offer him to Your forgiveness. Richard Wagner: Pilgrims’ chorus (from Tannhäuser) [Men’s choir and organ] The action of Tannhäuser, completed in 1845, takes place in the early thirteenth century and revolves around the tension between spiritual and erotic love, embodied in a song contest between the poet knights Wolfram von Eschenbach and Tannhäuser. In Act III a group of elderly pilgrims returns from Rome bearing the papal staff which, by bursting into leaf, has revealed God’s forgiveness of Tannhäuser’s very public praise of sensual passion. Beglückt darf nun dich, o Heimat, ich schau’n und grüssen froh deine lieblichen Auen; nun lass’ ich ruh’n den Wanderstab, weil Gott getreu ich gepilgert hab’. Durch Sühn’ und Buss’ hab’ ich versöhnt den Herren, dem mein Herze fröhnt, der meine Reu’ mit Segen krönt, den Herren, dem mein Lied ertönt! Der Gnade Heil ist dem Büsser beschieden, er geht einst ein in der Seligen Frieden; vor Höll’ und Tod ist ihm nich bang’, drum preis’ ich Gott mein Lebenlang. Halleluja! Halleluja in Ewigkeit! Blest, I may now look on thee, my homeland, and gladly greet thy pleasant pastures; now I lay my pilgrim’s staff aside to rest, because, faithful to God, I have completed my pilgrimage. Through penance and repentance I have propitiated the Lord, whom my heart serves, who crowns my repentance with blessing, the Lord to whom my song goes up! The salvation of pardon is granted the penitent, in days to come he will walk in the peace of the blessed; hell and death do not appal him, therefore will I praise God all my life. Alleluia! Alleluia in eternity! Giuseppe Verdi: Brindisi (from La traviata) [Soprano and tenor soli, choir and piano] Francesco Maria Piave’s libretto for Verdi’s La traviata, first performed in 1853, was a fairly faithful reproduction of Alexandre Dumas’ La dame aux camélias about a high-living courtesan who sacrifices herself for love, and who ultimately appears to be the victim of society before dying of consumption. As the opera opens a lavish party is taking place at the fashionable heroine Violetta’s house. Alfredo is in love with her and he calls on the assembled guests to raise their glasses, a request which is taken up by the chorus and then repeated by Violetta. ALFREDO (Tenor) Libiamo ne’ lieti calici, che la bellezza infiora; e la fuggevol ora s’inebrii a voluttà. Libiam ne’ dolci fremiti che suscita l’amore, poiché quell’occhio al core omnipotente va. Libiamo, amor fra i calici più caldi baci avrà. ALFREDO (Tenor) Let’s drink from the joyous chalice where beauty flowers; let the fleeting hour to pleasure’s intoxication yield. Let’s drink to love’s sweet tremors, to those eyes that pierce the heart. Let’s drink to love – to wine that warms our kisses. CHORUS Ah! Libiam, amor fra’ calici più caldi baci avrà. CHORUS Ah! Let’s drink to love – to wine that warms our kisses. VIOLETTA (Soprano) Tra voi saprò dividere il tempo mio giocondo; tutto è follia nel mondo ciò che non è piacer. Godiam, fugace e rapido è il gaudio dell’amore; e un fior che nasce e muore, né più si può goder. Godiam! C’invita un fervido accento lusinghier. VIOLETTA (Soprano) With you I would share my days of happiness; everything is folly in this world that does not give us pleasure. Let us enjoy life, for the pleasures of love are fleeting, as a flower that lives and dies and can be enjoyed no more. Let’s take our pleasure while its brilliant summons lures us on. CHORUS Ah! Godiamo! La tazza e il cantico la notte abbella e il riso, in questo paradise ne scopra il nuovo di. CHORUS Ah! Let’s take our pleasure of wine and singing and mirth till the new day dawns on us in paradise. VIOLETTA La vita è nel tripudio. VIOLETTA Life is just pleasure. ALFREDO ALFREDO Quando non s’ami ancora… But if one still waits for love… VIOLETTA Nol dite a chi l’ignora… VIOLETTA I know nothing of that – don’t tell me… ALFREDO E il mio destin cosi. ALFREDO But there lies my fate. ALL Ah! Sì godiamo la tazza e il cantico, &c. ALL Ah! Let’s take our pleasure of wine and singing, &c. ---- I N T E R V A L ---Richard Wagner: Procession & chorale (from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg) [Choir and organ] Wagner’s monumental comic opera, first performed in 1868, is a jolly, bourgeois antithesis to the aristocratic drama of Tannhäuser, the nucleus of both stories being a singing contest. But in contrast to the noble tormented mediaeval knights of the earlier work, Die Meistersinger features the good-natured, quarrelsome, sentimental town craftsmen of sixteenth century Nuremberg. The traditional, more mundane values of two worthies, the cobbler poet Hans Sachs and the town clerk Beckmesser, are challenged by the young revolutionary Walther, who wins the hand of Eva as the prize at the midsummer song contest. As the inhabitants gather for the contest on the meadow in front of the town in Act III the procession of the guild-singers (the mastersingers) is heard. When Sachs, the upholder of the tradition of true German art, appears, he is acclaimed by the crowd, who launch into one of his own compositions, a song in praise of the dawn. LEHRBUBEN Silentium! Silentium! Macht kein Reden und kein Gesumm’! APPRENTICES Silence! Silence No talking and no murmuring! ALLES VOLK Ha! Sachs! ’s ist Sachs! Seht, Meister Sachs! Stimmt an! Stimmt an! Stimmt an! “Wach’ auf, es nahet gen den Tag; ich hör singen im grünen Hag ein wonnigliche Nachtigall, ihr Stimm’ durchdringet Berg und Tal; die Nacht neigt sich zum Occident, der Tag geht auf von Orient, die rotbrünstige Morgenröt her durch die trüben Wolken geht.” EVERYONE Ha! Sachs! It’s Sachs! Look, Master Sachs! Begin! Begin! Begin! “Awake! the dawn is drawing near; I hear a blissful nightingale singing in the green grove, its voice rings through hill and valley; night is sinking in the west, the day arises in the east, the ardent red glow of morning approaches through the gloomy clouds.” Heil! Heil! Heil dir, Hans Sachs! Heil Nürnbergs Sachs! Heil Nürnbergs teurem Sachs! Hail! Hail! Hail to you, Hans Sachs! Hail to Nuremberg’s Sachs! Hail to Nuremberg’s dear Sachs! Giuseppe Verdi: Chorus of the Hebrew slaves (from Nabucco) [Choir and piano] Completed in 1842, Nabucco was Verdi’s third opera and is set in Babylon and Jerusalem in the aftermath of the defeat of the Hebrew armies by Nebuchadnezzar (Nabucco). One of its most notable aspects is its bold use of the chorus as an active protagonist in the drama, and the melody of the chorus sung by the Israelites to a paraphrase of Psalm 137 played a large part in the opera’s success. This great lament for the loss of the Israelites’ homeland became widely interpreted as a political gesture and was taken up as the anthem of Italian patriotism. Va, pensiero, sull’ali dorate; va, ti posa sui clivi, sui colli, ove olezzano tepide e molli l’aure dolci del suolo natal! Dearest homeland, my thoughts fly towards you; wings of gold bear them on to journey’s ending; where the sweet scented breezes are blending in the green hills and vales of our land! Del Giordano le rive saluta, di Sïone le torri atterrate… Oh mia patria sì bella e perduta, oh membranza sì cara e fatal! Ah! to stand by the banks of the Jordan and to see Zion’s woeful desolation… O dear land, once the joy of our nation, now forever lost by Fate’s cruel hand! Arpa d’ôr dei fatidici vati, perché muta dal salice pendi? Le memorie nel petto raccendi, ci favella del tempo che fu! Golden harps of the prophets and seers of old, why so silently hang on the willows? Lift your voice, stir our hearts, let the story be told of the times now so long gone and past. O simile di Solima ai fati traggi un suono di crudo lamento? O t’ispiri il Signore un concento che ne infonda al patire virtù! O Jerusalem, blessed city, when will grief and lamenting be over? Let our song rise to you, great Jehovah; hear the voice of your people at last! Richard Wagner: Träume [No.5 of Wesendonck Lieder] [Soprano and piano] Wagner produced little outside his operatic oeuvre, hardly surprising given the sheer scale of his work in that field. Two works that have continued to command attention are the short orchestral chamber piece Siegfried Idyll and the song-cycle Wesendonck Lieder, to poems by Mathilde Wesendonck, which he put together between November 1857 and May 1858 as he was working on Tristan und Isolde. Mathilde was the wife of one of Wagner’s patrons, and they became infatuated with one another, which contributed to the intensity in the conception of the opera. The five poems that make up the cycle are in a wistful pathos-laden style; when he came to set them, Wagner called the third and fifth of them ‘studies’ for Tristan und Isolde, the roots of the love duet in Act II of the opera being discernible in Träume (Dreams). They were originally written for female voice and piano, but he produced a chamber orchestra version of Träume to be played below Mathilde’s window on her birthday in December 1857. The song-cycle was first performed as a whole in July 1862. Sag, welch wunderbare Träume halten meinen Sinn umfangen, dass sie nicht wie leere Schäume sind in ödes Nichts vergangen? Tell me, what kind of wondrous dreams are embracing my senses, that have not, like sea-foam, vanished into desolate nothingness? Träume, die in jeder Stunde, jedem Tage schöner blühn, und mit ihrer Himmelskunde selig durchs Gemüte ziehn! Dreams, that with each passing hour, each passing day, bloom fairer, and with their heavenly tidings roam blissfully through my heart! Träume, die wie hehre Strahlen in die Seele sich versenken, dort ein ewig Bild zu malen: allvergessen, eingedenken! Dreams which, like holy rays of light sink into the soul, there to paint an eternal image: forgiving all, thinking of only one. Träume, wie wenn Frühlingssonne aus dem Schnee die Blüten küsst, dass zu nie geahnter Wonne sie der neue Tag begrüsst, Dreams which, when the spring sun kisses the blossoms from the snow, so that into unsuspected bliss they greet the new day, Dass sie wachsen, dass sie blühen, träumend spenden ihren Duft, sanft an deiner Brust verglühen, und dann sinken in die Gruft. so that they grow, so that they bloom, and dreaming, bestow their fragrance, these dreams gently glow and fade on your breast, and then sink into the grave. Richard Wagner: Spinning chorus (from Der fliegende Holländer) [Ladies’ choir and piano] Der fliegende Holländer, completed in 1842, is the earliest of Wagner’s music dramas to have remained in the popular canon. The story of the Dutch sea-captain condemned by the Devil to sail the oceans for eternity unless he finds a faithful woman to redeem him elicited from the composer one of his most overtly dramatic scores. At the beginning of Act II, in the Norwegian port where the Dutchman is moored, the women sing as they spin, while the story’s heroine Senta gazes at a portrait of the mythical Flying Dutchman in the first stirrings of her love for him. Summ’ und brumm’, du gutes Rädchen, munter, munter, dreh’ dich um! Spinne, spinne tausend Fädchen, gutes Rädchen, summ’ und brumm’! Mein Schatz is auf dem Meere draus, er denkt nach Haus an’s fromme Kind; mein gutes Rädchen, braus’ und saus’! Ach, gäbst du Wind, er kam geschwind! Spinnt! Spinnt! Fleissig, Mädchen! Brumm’! Summ’! Gutes Rädchen! Hum and buzz, good wheel, gaily, gaily turn! Spin, spin a thousand threads, good wheel, hum and buzz! My love is out at sea, he thinks of home and his true maid; my good wheel, hum and sing! Ah, if you drove the wind, he’d soon be here. Spin! Spin! Set to, girls! Buzz! Hum! Good wheel! Summ’ und brumm’, &c. Mein Schatz, da draussen auf dem Meer, im Süden er viel Gold gewinnt; ach, gutes Rädchen, saus noch mehr! Er gibt’s dem Kind, wenn fleissig spinnt, Spinnt! Spinnt! &c. Hum and buzz, &c. My love out there at sea has won much gold in the south; Ah, good wheel, turn faster! He’ll give it to his girl if she spins well. Spin! Spin! &c. Giuseppe Verdi: Te Deum [No.4 of Quattro pezzi sacri] [Soprano solo, choir and organ] [See under Stabat Mater for general background notes on the Te Deum] The Te Deum, Verdi’s most harmonically advanced work, is scored for a solo soprano, two four-part choirs, and a large orchestra (replaced by the organ this evening). It has been described as the greatest setting of the Te Deum ever written, not on grounds of size but on Verdi’s achievement in his quite astonishingly dramatic interpretation of not just the sense of the words of the liturgy, which are set verbatim and without repetition, but also of its historical background. Although born into a Catholic family Verdi remained something of a free thinker for whom religion did not hold a special place. Consequently he did not cultivate a separate, specifically religious style for his sacred music, but by paying close attention to the detail of the texts and by applying the same methods that he used in composing his operas he created works that make their impact through the acting out of intense human dramas. After the opening unaccompanied plainchant melody the work progresses with strong rhythmic contrasts and dynamic variations that precisely match the ebb and flow of the words. In the most emphatic sections, those directly praising the Almighty and those appealing for divine guidance, Verdi underlines the message of the text by having the choir sing in unison. Elsewhere the choral parts and the lines in the accompaniment interweave as befits a universal hymn of praise. This collective celebration is heightened by the use of an eight-part chorus: after all the subject of the entire hymn is in the first person plural. But right at the end of the liturgy the subject changes to the first person singular (In Thee have I trusted), and there emerges a single soprano voice reiterating this appeal ever more loudly and cogently, to be joined at the last by the full chorus, with the sopranos rising questioningly and spectacularly to a thrilling top B natural. But the accompaniment has the last say, playing out the work to a shimmering pianissimo, suggesting perhaps, as one commentator has noted, that God does indeed move in a mysterious way. Verdi knew he had created something special in his Te Deum, for he expressed the wish to have, of all his many great compositions, a score of this work buried with him. GC Te Deum laudamus, te Dominum confitemur. Te aeternum Patrem omnis terra veneratur. Tibi omnes Angeli, tibi coeli et universae potestates. Tibi Cherubim et Seraphim, incessabili voce proclamant: ‘Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus, Dominus Deus Sabaoth. Pleni sunt coeli et terra majestatis gloriae tuae.’ Te gloriosus Apostolorum chorus; Te Prophetarum laudabilis numerus; Te Martyrum candidatus laudat exercitus. Te per orbem terrarium sancta confitetur Ecclesia: Patrem immensae majestatis; Venerandum tuum verum, et unicum Filium; Sanctum quoque Paraclitum Spiritum. Tu, Rex gloriae, Christe. Tu Patris sempiternus es Filius. Tu ad liberandum suscepturus hominem, non horruisti Virginis uterum. Tu devicto mortis aculeo, aperuisti credentibus regna coelorum. Tu ad dexteram Dei sedes, in Gloria Patris. Judex crederis esse venturus. Te ergo quaesumus tuis famulis subveni, quos pretioso sanguine redemisti. Aeterna fac cum Sanctis tuis, in Gloria numerari. Salvum fac populum, Domine, et benedic haereditati tuae; Et rege eos, et extolle illos usque in aeternum. Per singulos dies benedicamus te; et laudamus nomen tuum in saeculum saeculi. Dignare, Domine, die isto sine peccato nos custodire. Miserere nostri Domine. Fiat misericordia tua, Domine, super nos, quemadmodum speravimus in te. In te speravi; non confundar in aeternum. In te, Domine, in te speravi. We praise Thee, O God, we acknowledge Thee to be the Lord. All the earth doth worship Thee, the Father everlasting. To Thee all Angels cry aloud, the heavens and all the powers therein. To Thee cherubim and seraphim continually do cry: ‘Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of Sabaoth. Heaven and earth are full of the majesty of Thy glory.’ The glorious company of the Apostles; The goodly fellowship of the Prophets; The noble army of martyrs, praise Thee. The Holy Church throughout all the world doth acknowledge Thee: the Father of an infinite majesty; Thine honourable and only Son; Also the Holy Ghost, the Comforter. Thou art the King of Glory, O Christ. Thou art the everlasting Son of the Father. When Thou tookest upon Thee to deliver man, Thou didst not abhor the Virgin’s womb. When Thou hadst overcome the sharpness of death, Thou didst open the Kingdom of Heaven to all believers. Thou sittest at the right hand of God, in the glory of the Father. We believe that Thou shalt come to be our judge. We therefore pray Thee, help Thy servants, whom Thou hast redeemed with Thy precious blood. Make them to be numbered with Thy saints in glory everlasting. O Lord, save Thy people, and bless Thine heritage. Govern them, and lift them up for ever. Day by day we magnify Thee; and we worship Thy name, ever world without end. Vouchsafe, o Lord, to keep us this day without sin. O Lord, have mercy upon us. O Lord, let Thy mercy lighten upon us as our trust is in Thee. In Thee have I trusted: let me never be confounded. In Thee, Lord, in Thee have I trusted. Dumfries Choral Society The origins of the Society can be traced back to 1863, when it was founded as Dumfries and Maxwelltown Choral Society, continuing without break until 1915. At that point its activities appear to have lapsed, presumably because of the First World War, and, although a few minor contributions were made to a series of subscription concerts at the Lyceum Theatre between 1919 and 1921, no formal choral activity during the next thirty years has been identified. In 1943 Edward Murray, the headmaster of St John’s School, started up a small choir which met on Monday evenings in St John’s Church, with the curate accompanying on the organ. As the numbers increased, Murray proposed the formation of a choral society; this came about, and the first concert took place on 30th March 1944, with Murray conducting a performance of Handel’s Messiah in St John’s Church. The Choir Sopranos Jill Asher Julia Bell Morag Blair Melody Campbell Pauline Cathcart Lesley Creamer Julie Dennison Valerie Fraser Clare Hodge Rosie Isles Elizabeth Meldrum Pam Mitchell Daveen Morton Alison Robertson Vera Sutton Anne Twiname Elise Wardlaw Margaret Young Barbara Kelly Claire McClurg Margaret Mctaggart Audrey Marshall Sheena Meek Emma Munday Margaret Newlands Fiona Power Nina Rennie Nancie Robertson Janet Shankland Contraltos Marilyn Callander Eileen Cowan Christine Dudgeon Jill Hardy Jenny Hope-Srobat Nan Kellar Tenors Ann Beaton Fraser Clark Ian Crosbie Keith Dennison Katharine Holmes Ben Hughes Brenda MacLeod Fraser McIntosh Rhona Pringle Basses Malcolm Budd Peter Clements Geoff Creamer Douglas Dawson George Ferguson Brian Power Mike Shire Norris Thomson Cover and poster design: Gwen Adair Printer TK Print Anyone wishing to support the Society financially via the Internet at no extra charge can find out more by looking us up on the Easyfundraising web site: http://www.easyfundraising.org.uk Elite Display Dumfries Choral Society: The Aberdour Hotel Dates for your Diary: Saturday 14 December 2013 Saturday 26 April 2014 Christmas Concert, St John’s Church 7pm Durufle: Requiem Vaughan Williams: Dona Nobis Pacem St John’s Church 7.30pm (note earlier start time) in aid of the Bhopal Medical Appeal in the lead up to the 30th anniversary of the toxic chemical leak in Bhopal, India, in 1984 If you would like to be added to our email list for details of future concerts, please contact us via our web site. Dumfries Music Club 2013 – 2014 Dates: Friday 22.11.13 Thursday 05.12.13 Friday 17.01.14 Thursday 13.02.14 Thursday 27.02.14 Dumfries Choral Society is a member of Making Music Scotland www.dumfrieschoralsociety.org.uk Scottish Charity Number SC002864 Friday 14.03.14