File - The Trokan Website

advertisement

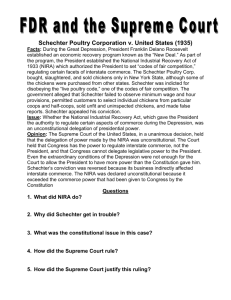

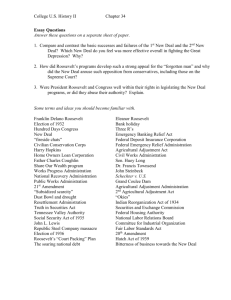

Schechter v. U.S. (1935) In the midst of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt worked with the Democratic Congress to enact several sweeping economic reform bills, known as the New Deal. In 1935, in A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional a central piece of this New Deal legislation. In reviewing the conviction of a poultry company for breaking the Live Poultry Code, the Court held that the code violated the Constitution's separation of powers because it was written by agents of the president with no genuine congressional direction. The Court also held that much of the code exceeded the powers of Congress because the activities it policed were beyond what Congress could constitutionally regulate. The Live Poultry Code, written and promulgated by the Roosevelt administration in 1934, was a part of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), a law passed by Congress to regulate companies as a means to combat the Great Depression. Section 3 of NIRA gave the president authority to approve such "codes of unfair competition." Roosevelt's poultry code fixed the maximum number of hours a poultry employee could work, imposed a minimum wage for poultry employees, and banned certain methods of "unfair competition." Schechter Poultry Corporation, the defendant in the case, purchased live poultry from commissioners in New York City and Philadelphia and sold slaughtered poultry to retailers and butchers in Brooklyn. Schechter was charged by the U.S. government with violating the poultry code by selling "unfit chickens," illegally selling chickens on an individual basis, avoiding inspections by local poultry regulators, falsifying records of poultry sold, and selling poultry to nonlicensed purchasers. Schechter was convicted in a federal district court, lost an appeal to the circuit court, and appealed to the Supreme Court, which reviewed the case in 1935. The Supreme Court held that the Live Poultry Code was unconstitutional and that the conviction of Schechter must be overturned. First, the Court found that the president lacked the power to write the code, citing the U.S. Constitution, Article I, which states that all legislative power is to be vested in the Congress. Article I is thus violated if Congress grants its exclusive legislative power to the president. The NIRA allowed the president to write new codes, such as the poultry code, so long as they regulated "unfair competition." The Court found the phrase "unfair competition" too ambiguous to constitute an "intelligible principle" necessary to limit the president's actions in enforcing the NIRA. Lacking such a principle, the NIRA effectively allowed the president "unfettered discretion" to create "new laws" without congressional approval. Second, the Court held that the poultry code violated the Constitution's Commerce Clause. The Constitution limits the activities over which Congress may legislate, reserving all other activities for the states to govern. While the Constitution allows Congress to regulate "interstate commerce" under the clause, the Court found Schechter's activities had nothing to do with interstate commerce. Schechter bought poultry from out of state, but its offending conduct was confined to New York State. The activities of Schechter thus fell outside congressional power because they constituted intrastate (instate) commerce. Additionally, some provisions of the poultry code were found unconstitutional on their face. The effect of a butcher's hours and wage practices on interstate commerce, for example, was found far too "indirect" to be within the congressional powers to regulate under the Commerce Clause. Schechter Poultry's sweeping interpretations of legislative power had devastating effects on President Roosevelt's New Deal programs in the 1930s. The centerpiece of the New Deal legislation, the NIRA, was essentially declared unconstitutional. Ultimately, President Roosevelt responded by proposing a "court packing" scheme in 1937, allowing a new Supreme Court justice to be appointed for every current sitting justice over the age of 70. The scheme was designed to help tip the Court's ideological balance to Roosevelt's side. It failed in Congress and never became law. By the late 1930s, however, the Supreme Court began reading Congress's powers under the Commerce Clause more broadly. Indeed, by the 1960s, the Court held that congressional statutes outlawing racial segregation in local businesses were constitutional under the Commerce Clause. Father Charles Coughlin – Source – Library of Congress Father Coughlin first took to the airwaves in 1926, broadcasting weekly sermons over the radio. By the early 1930s the content of his broadcasts had shifted from theology to economics and politics. Just as the rest of the nation was obsessed by matters economic and political in the aftermath of the Depression, so too was Father Coughlin. Coughlin had a well-developed theory of what he termed "social justice," predicated on monetary "reforms." He began as an early Roosevelt supporter, coining a famous expression, that the nation's choice was between "Roosevelt or ruin." Later in the 1930s he turned against FDR and became one of the president's harshest critics. His program of "social justice" was a very radical challenge to capitalism and to many of the political institutions of his day. Father Coughlin was an early and passionate supporter of President Roosevelt, since he viewed FDR as a radical social reformer like himself. Roosevelt's rhetoric during his inaugural address implicitly promised to "drive the money changers from the temple." This was music to Coughlin's ears since a core part of his own message was monetary reform. Roosevelt's early monetary policy seemed to fulfill this promise and so Coughlin viewed him as the savior of the nation. But when FDR failed to follow-on with additional radical reforms, Coughlin turned against him. By 1936, he would support a third-party candidacy against FDR's reelection bid and would even say this of Roosevelt: "The great betrayer and liar, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who promised to drive the money changers from the temple, had succeeded [only] in driving the farmers from their homesteads and the citizens from their homes in the cities. . . I ask you to purge the man who claims to be a Democrat, from the Democratic Party, and I mean Franklin Double-Crossing Roosevelt." Father Coughlin's influence on Depression-era America was enormous. Millions of Americans listened to his weekly radio broadcast. At the height of his popularity, one-third of the nation was tuned into his weekly broadcasts. In the early 1930s, Coughlin was, arguably, one of the most influential men in America. Although his core message was one of economic populism, his sermons also included attacks on prominent Jewish figures--attacks that many people considered evidence of anti-Semitism. His broadcasts became increasingly controversial for this reason, and in 1940 his superiors in the Catholic Church forced him to stop his broadcasts and return to his work as a parish priest. Huey Long - Share Our Wealth - Source – Huey Long Foundation In a national radio address on February 23, 1934, Louisiana Governor Huey Long unveiled his “Share Our Wealth” plan (also known as Huey Long's "Share the Wealth" plan), a program designed to provide a decent standard of living to all Americans by spreading the nation’s wealth among the people. Long proposed capping personal fortunes at $50 million each (roughly $600 million in today's dollars) through a restructured, progressive federal tax code and sharing the resulting revenue with the public through government benefits and public works. In subsequent speeches and writings, he revised his graduated tax levy on wealth over $1 million to cap fortunes at $5 - $8 million (or $60 - $96 million today). Share Our Wealth Proposal Cap personal fortunes at $50 million each — equivalent to about $600 million today (later reduced to $5 - $8 million, or $60 - $96 million today) Limit annual income to one million dollars each (about $12 million today) Limit inheritances to five million dollars each (about $60 million today) Guarantee every family an annual income of $2,000 (or one-third the national average) Free college education and vocational training Old-age pensions for all persons over 60 Veterans benefits and healthcare A 30 hour work week A four week vacation for every worker Greater regulation of commodity production to stabilize prices Long advocated free higher education and vocational training, pensions for the elderly, veterans benefits and health care, and a yearly stipend for all families earning less than one-third the national average income – enough for a home, an automobile, a radio, and the ordinary conveniences. Long also proposed shortening the work week and giving employees a month vacation to boost employment, along with greater government regulation of economic activity and production controls. He later proposed a debt moratorium to give struggling families time to pay their mortgages and other debts before losing their property to creditors. Long charged that the nation’s economic collapse was the result of the vast disparity between the super-rich and everyone else. A recovery was impossible while 95% of the nation’s wealth was held by only 15% of the population. In Long’s view, this concentration of money among a handful of wealthy bankers and industrialists restricted its availability for average citizens, who were already struggling with debt and the effects of a shrinking economy. Because no one could afford to buy goods and services, businesses were forced to cut their workforces, thus deepening the economic crisis through a devastating ripple effect. “Our present plan is that we will allow no one man to own more than $50 million,” Long told the radio audience of millions. "It may be necessary, in working out the plans that no man's fortune would be more than $10 or $15 million. But be that as it may, it will still be more than any one man, or any one man and his children and their children, will be able to spend in their lifetimes; and it is not necessary or reasonable to have wealth piled up beyond the point where we cannot prevent poverty among the masses.” Long believed that it was morally wrong for the government to allow millions of Americans to suffer in abject poverty when there existed a surplus of food, clothing, and shelter. He blamed the mass suffering on a capitalist system run amok and feared that impending civil unrest threatened the democracy. By 1934, nearly half of all American families lived in poverty, earning less than $1,250 annually.