Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder is a chronic disorder that

advertisement

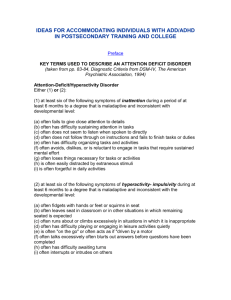

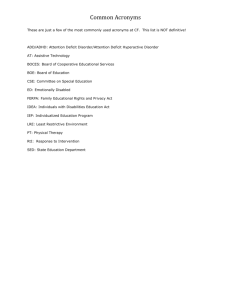

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder is a chronic disorder that affects million of children and adults worldwide. It is characterized by a combination of symptoms including difficulty sustaining attention, and hyperactive and impulsive behavior (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2011). AD/HD is diagnosed based on a combination of hyperactive and inattention symptoms in at least two different environments where adult and peer relationships have begun to suffer. The problems associated with AD/HD become most apparent during the elementary school years. There are many symptoms of AD/HD and it is important to be able to differentiate them from normal childhood behavior. One set of symptoms associated with AD/HD illustrate the inability to maintain attention. These symptoms include difficulty staying focused, difficulty completing tasks such as schoolwork and chores, dislike of tasks requiring sustained mental effort, difficulty organizing tasks, and forgetfulness (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2011). The other set is comprised of hyperactive and impulsive behavior. These symptoms include fidgeting, difficulty sitting still, difficulty playing quietly, difficulty waiting for one’s turn, excessive talking, and frequently interrupting (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2011). These symptoms must be differentiated from normal child behavior. One important aspect of AD/HD is that the symptoms appear in more than one setting. For example, if a child has trouble difficulty paying attention or sitting still at school but still normally performs chores and interacts with parents and siblings, he/she probably has does not have AD/HD. If children are experiencing trouble completing tasks, listening and concentrating in every setting they are more likely to have AD/HD. Children are placed along the continuum according to their symptoms. Children who display only attention deficit symptoms and not hyperactivity symptoms may be called ADD. Boys are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with AD/HD than girls. Children may be misdiagnosed, as some symptoms of AD/HD are similar to symptoms of other physical and mental health problems. A “zebra”—a health problem that can be masked by the symptoms of AD/HD—can be more complicated. These zebras can be physical. They can include hearing and seeing problems, thyroid disease, anemia, hypoglycemia, diabetes, seizure disorder, post concussion syndrome, sleep apnea, and the effects of foods or prescription and nonprescription drugs. For example, some girls are diagnosed with AD/HD, without the hyperactivity because they lack the ability to focus and maintain attention. However it was discovered that they actually have hypothyroidism, and when treated for this condition had much higher energy levels and performed better in school and social situations (Barnhill). Diabetes mellitus causes blood sugar to be high, and for many children this results in hyperactive behavior and a misdiagnosis of AD/HD (Barnhill). Hormone disorders can also be to blame when a child is either inattentive and fatigued, or has mood swings including hyperactivity. They can also be other mental health disorders. These include depression, manic depression, and other learning disabilities (Barnhill). Manic depression, especially, can cause inattentiveness and hyperactive behavior. All of these conditions can be treated and will help to change the AD/HD-like symptoms. AD/HD does not have one clear cause; there are several risk factors that parents should be aware of. Exposure to toxins such as smoke, alcohol, or drugs in the womb may cause AD/HD. Also, exposure to environmental toxins and to certain food additives may be to blame. Heritability has been closely linked to AD/HD. If family members have AD/HD, a child is far more likely to also have it. Genetics are reported as the primary cause. There are many complications that can occur with AD/HD, especially other mental health disorders. Most importantly, this includes other learning disabilities and emotional problems. Children with AD/HD are more likely to become depressed or have an anxiety disorder. AD/HD will affect the social-emotional, and cognitive growth of the child. In early childhood peer relationships and the ability to perform tasks is not vital. In the preoperational phase children are not truly self-aware. In early childhood, interaction with one’s peers is sparse. Pre-school age children (3-4 year-olds) often play around each other and cannot truly be “inside each other’s heads” (Belsky 2010). In middle/late childhood friendship, popularity, and academic performance are highly linked to self-esteem and personal growth. “During elementary school we first wake up to the realities of life. We understand that we are not just completely wonderful. We need to work for what we want to achieve. We are vulnerable to feeling inferior, to having the painful sense that we don’t measure up” (Belsky 2010). School life greatly influences children’s self-esteem. Children with AD/HD have more difficulty making and keeping friends because of their inability to follow instructions and their impulsive behavior. “According to Harter, children draw on five areas to determine their overall self-esteem: scholastic competence (their academic talents); behavioral conduct (whether they are obedient or “good”); athletic skills (their performance at sports); peer likeability (their popularity with other children); and physical appearance (their looks)” (Belsky 2010). AD/HD causes many different behaviors that will impact a child’s self-esteem. Scholastic competence will be affected by the child’s inability to focus on tasks and organize thoughts. Also, impulsive behavior, inability to sit still, and excessive talking will hinder academic performance. Even very gifted children will run into academic difficulties when they are struggling with AD/HD. Behavioral conduct is difficult to control for children with AD/HD. They act impulsively and often cannot wait their turn. Following instructions in a classroom setting maybe very challenging. In sports, children with AD/HD are more likely to have difficulty following the rules. Children with AD/HD notoriously have trouble with their peers. Behavioral conduct and academic performance in middle and late childhood often dictate popularity. Following the rules and interacting with adults appropriately is essential to child popularity (Belsky 2010). For children with AD/HD tasks like getting themselves ready in the morning are more difficult because they have trouble focusing and organizing. This means that they might go to school with their teeth not brushed or their hair not combed. This may cause feelings of inferiority in the category of physical appearance. Until about age seven, children are in the preoperational stage of cognitive development. They do not have the intellectual tools to understand a lot of academic concepts (Belsky 2010). At this point the most important part of learning is placing things into categories and understanding more of the world as children get more aware of the things around them. In middle childhood children reach the concrete operational stage, which allows them to conserve, reverse, and perform other tasks that are key to academic success. Once the majority of children have reached this stage, schoolwork becomes more complex and requires more thought and focus. Children with AD/HD have difficulty in school because they have trouble following directions, completing tasks, and organizing thoughts. Their inability to complete tasks efficiently becomes much more of a challenge in middle and late childhood than it would in early childhood. Cognitively, children develop in stages that build on each other. Skills build on top of each other. During early childhood skills are basic and tend to be less structured. For many children, AD/HD is not even recognizable during this time. However, to work effectively with children who have AD/HD, parents and teachers need to assess what is in their ability to accomplish, which will probably include giving shorter instructions and breaking up concentration time. Physically, children with AD/HD have trouble developing their fine motor skills and may suffer the physical side effects of medication. I interviewed three people, leading to my belief that people have a mixture of correct and incorrect knowledge about AD/HD. When asked what they knew about the symptoms of AD/HD, all three of my interviewees were able to name a set of common symptoms including inattention, restlessness, and inability to concentrate. When asked about treatment options, two of my three interviewees knew only about the medications and talk therapy as treatment. However, one interviewee knew that there are other strategies and home remedies to help with the disorder. I believe that this shows a basic misunderstanding about AD/HD, and its treatability. Finally, all of my interviewees knew that there is a difference between attention deficit and hyperactivity, however, none showed a great understanding of what set the two apart. I think that this highlights the misunderstanding of how AD/HD affects people. It is not often thought of as a continuum of symptoms and is often just seen as one very uncontrollable child. There are many misconceptions about AD/HD; one common misconception is that every child who has the disorder must be medicated. Although medication is one of the options for treatment there are also other options that include different types of therapy as well as techniques that children and parents can use at home and at school. The most well known type of AD/HD medication is Ritalin. This is one of the stimulant drugs that are prescribed to treat AD/HD. Stimulant drugs affect the neurotransmitters in the brain, which results in a change of behavior. This is especially effective in controlling hyperactive tendencies. These drugs do have side effects, which are not well-known. Stimulant medication can cause weight loss and trouble sleeping (Mayo Clinic). However, it has also been linked to heart problems. “In February, the FDA's Drug Safety and Risk Management advisory committee voted to recommend the agency add the strongest possible warning to some of the drugs, in that case to alert doctors, patients and parents of the uncertainty regarding the risk they may pose to the cardiovascular system.” (Packet) These medications have been linked to several different health concerns especially in children. The greatest debate is between those who are concerned for the mental health of children and those who are concerned fro their physical health. However, there are other options for treatment. Non-stimulant drugs are used to treat AD/HD. These are mainly used when stimulant medication has side effects. Non-stimulant medication can also treat hyperactive and inattentive behavior, but has also been found effective in treating anxiety. In a small population, these have been found to cause liver damage. There are many different therapy techniques that have been found very successful. These include psychotherapy, behavioral therapy, and family therapy. Parental skills lessons are also provided for many families (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2011). Other alternative therapies include special dietary changes, yoga and meditation, and neurofeedback therapy. These mostly teach children how to control their behavior and focus on tasks. As an elementary school teacher, it will be vital for me to understand the troubles associated with AD/HD and the techniques that can help mitigate problems in the classroom. Affecting four million children, AD/HD is the highest-ranking mental health problem in children in the United States (Belsky 2010). With this statistic in mind, it is almost guaranteed that I will encounter children with AD/HD in my classroom. As such, I must know how to tell the difference between normal behavior and this disorder and how to best control the environment to give children with AD/HD the best possible experience in the classroom and as a learner. An important aspect to understanding AD/HD is being able to apply techniques and skills to the classroom. “Modifications should be made in the classroom setting to allow a child with AD/HD to better succeed. Additionally, these modifications help to teach the child with AD/HD coping mechanisms which they can selfemploy in the future” (CNN). It is important for teachers to make environmental adjustments and focus on success. As a teacher I can ensure that I place children in a place of minimal distractions, away from open spaces. I can make sure I explain directions quickly, to ensure that all of my students pay attention and are able to accomplish their assignments. Most importantly I can focus on success. Children with AD/HD often develop depression or anxiety disorders which are exacerbated by the difficulties they have academically and socially. As a teacher it will be my job to ensure that I do everything in my power to encourage success from all of my students. This includes not allowing them to be labeled as troublemakers or bad students just because they have this disorder.

![What Is Language? What Is Speech? [en Español] Kelly`s 4-year](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007027130_1-6ae911bbc18a3f7f2409aa622adfa71a-300x300.png)