The Futility Dilemma: A More Effective Approach

advertisement

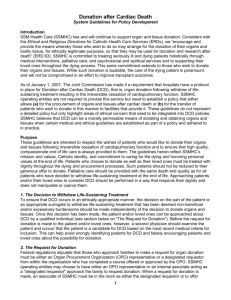

Welcome to GRAND ROUNDS Welcome To Grand Rounds Ethical Dilemmas in Clinical Practice Practical Ideas for Solutions Michael R. Panicola, PhD Corporate Vice President, Ethics SSM Health Care michael_panicola@ssmhc.com I have nothing to disclose. Objectives 1) Review real-life cases that raise complex, challenging ethical issues in health care delivery 2) Discuss practical ideas & strategies for how to address these types of cases 3) Provide relevant resources 3 Case 1: Medical Futility 4 Case Description • 81y/o female admitted over two months ago to SMH for an elective abdominal aortic aneurysm approximately 5 cm in diameter. Endovascular repair was unsuccessful & thus an open repair was performed. Patient initially seemed to be recovering well in the ICU but two weeks post-surgery developed multiple complications, including: ischemic bowel necessitating colon resection; urosepsis requiring antibiotic therapy; multiple pneumonias leading to tracheostomy & ventilation; ischemic stroke resulting in left-side hemiplegia & cognitive deficit; disseminated intravascular coagulation (or DIC) that has caused significant bleeding requiring frequent administration of platelets & fresh frozen plasma; & acute renal failure for which dialysis is necessary. Currently, the patient is in the ICU on mechanical ventilation at 100% oxygenation; still on antibiotics; receiving blood products every-other-day for the DIC; has a PEG tube for nutritional support; is mildly sedated for pain & rest; & has not moved left-side. The intensivist has approached the family numerous times in recent weeks about limiting treatment but the family will hear none of it & continues to insist that everything be done. All the physicians caring for the patient, with the exception of the vascular surgeon (at least publicly), feel strongly that current course of treatment is futile & a waste of scarce medical resources. Recently, the intensivist wrote a DNR order for the patient but when the family objected, threatening to bring suit against him & hospital, he rescinded it. 5 Questions for Discussion • What would you do if confronted with this case or asked your advice? • Is the family’s request to “do everything” acceptable? • Are there any limits to familial requests of this nature? If so, what are they? 6 Futility in Perspective • Requests or demands for “futile” treatment constitute one of the most intractable ethical challenges – Patient autonomy & physician integrity – Beneficence/nonmaleficence & distributive justice • #1 reason for ethics consults at end of life & major source of moral distress among patients/families & caregivers • Various attempts to address the issue go back well over 20 years but little progress 7 Three Generations of Futility • Futility: a concept in evolution. – Chest. 2007 Dec;132(6):1987-93. – Burns JP, Truog RD. • Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Anesthesia, Children's Hospital Boston and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA. 8 Three Generations of Futility (cont.) • Generation #1: defining futility (early 1990s) – Conditions – Quantitative versus qualitative • Generation #2: procedural approach (late 1990s) – Development of policies – Texas Advance Directives Act (1999) • Generation #3: communication & negotiation (present) – Patient/family engagement – Support for caregivers 9 What’s the Real Problem? • Patients/families – – – – Untimely, incomplete, & inconsistent information Inadequate time to make decision (“right now”) Fear of abandonment, lower level of care Uncertainty about patient’s wishes, “right” thing to do • Physicians & other caregivers – – – – Failure to establish goals, address other issues Poor, inconsistent exchange of information Lack of skill, nuance in presenting treatment options Reluctance to have “difficult conversations” 10 SSM’s 3rd Generation Approach • Development of guidelines & tools – “Enhancing Communication & Coordination of Care: Guidelines for Physicians & Other Caregivers” • Located on corporate ethics intranet site: http://my.ssmhc.com/SiteDirectory/corporateethics/Pag es/PoliciesandPositionStatements.aspx – Care Conference Facilitator Checklist & Resource Guide 11 A Look at the Guidelines Communication/Coordination • • • • • • • • Communicate early & often with patients/families Communicate early & often with other caregivers Determine goals of care & evaluate routinely Make time for & participate in care conferences Exercise care in offering/disc treatment options Address unreasonable requests up-front, candidly Ensure non-abandonment & quality end of life care Once the decision has been made… 12 A Look at the Guidelines Conflict Situations • Establish appropriate setting for conversation • Determine level of understanding – Fill in any gaps & allow time to absorb new info • Clarify hopes and expectations – Address unrealistic expectations & clarify any misconceptions • Discuss withholding or withdrawing treatment – Provide opinion – Offer alternative care options (hospice, PC) – Ensure non-abandonment • Respond to deeper needs – Remember first time for family – Identify underlying reasons request to do everything A Look at the Guidelines Conflict Situations • Devise a care plan (if agreement) • Lack of agreement – Ethics consult – Restrict treatment options in light of patient’s best interests • No treatment options that extend or increase the patient’s suffering (e.g., amputation of a limb for a patient with end-stage illness) or are medically contraindicated (e.g., ACLS at end of life) – Consider time-limited trial • Only if treatment in question does not extend or increase patient’s suffering & could perhaps achieve its physiological end – Consider withdrawing & offer family other options • Documentation • Debrief with & support caregivers A Look at the Guidelines Care Conferences • Definition – Meeting among the patient (if able), family/friends/supporters, & health care team designed to enhance communication & coordination of care • What patients? – Any seriously ill, complex patient but especially those with high mortality risk, multiple admissions, 3+ specialists, ICU LOS >5 days, or whose caregiver or family member requests one • Simple intervention validated for efficacy – Enhance communication & care coordination, reduce conflict situations, increase satisfaction, conserve resources, concordance with patient/family preferences 15 SSM St. Louis ICU Care Conference Pilot Project • Case manager (CM) driven – Serve as coordinators & facilitators • Patients assessed on daily rounds – Conferences for patients with predicted mortality >50, ICU LOS >5days, family/caregiver request, or change in treatment focus (e.g., comfort) or level of support (e.g., hospice) • Who attends? – Attending/primary treating physician, bedside nurse, patient (if able), key family members, and POA (if applicable) a must & others as appropriate 16 SSM St. Louis Care Conference Flowchart ICU patients assessed on daily rounds Meet at least one of these criteria: 1.MPM > 50 and ICU LOS > 5 days 2.Family/caregiver request 3.Need for change in treatment focus 4. Change in level of support (i.e. hospice) Yes List of conferences prioritized to no more than 2 pts per day CM contacts attending/primary treating MD for a meeting time w/in next 48 hours No Conference not needed Documentation of care conference is completed by CM Feedback from: • family •conference team Meeting date, time, and place are finalized Care Conference is held, CM facilitates Attending/primary treating physician, bedside nurse, patient (if able), key family members, and POA (if applicable) a must CM notifies the following of the meeting date, time, and place: •POA/Patient’s family •Consulting MD’s •Nursing staff •Pastoral care 17 Return to Case • Conflict already present, may even be intractable, but still need to… – – – – – Communicate frequently with family Focus everyone on patient’s best interests Attend to needs/distress of caregivers Provide high quality EoL care to patient Limit tx ineffective (CPR) or disproportionately burdensome • Learn from experience – – – – Approach patients/families earlier Set goals, establish care plan Communicate often & coordinate care among caregivers If conflict arises, negotiate don’t dominate Case 2: Donation After Cardiac Death (DCD) 19 Case Description • Steven, a 27 year-old with a history of drug abuse, presents to the ED of SMH following a cardiac arrest induced by a drug overdose. According to EMS, Steven was asystole upon arrival, perhaps for as long as 15 minutes, but was able to be resuscitated in the field. Steven was rapidly transferred to the ICU where he remained in a persistent coma with intermittent seizures. CT showed diffuse edema, EEG showed bilateral periodic epileptiform discharges (or PEDs), & a diagnosis of severe anoxic encephalopathy was made by the neurologist. After 14 days with no improvement, the neurologist informed the family that, while not brain-dead, Steven had little brain activity & an extremely poor prognosis for meaningful cognitive recovery. Treatment options were discussed & the family ultimately decided that Steven would not want to live like this & requested withdrawal of the ventilator. After this decision was made, a “designated requestor” on staff presented the family with the option of organ donation after cardiac death, which they accepted enthusiastically. The neurologist subsequently wrote an order for the withdrawal of treatment followed by organ donation. Upon being notified of the order, the intensivist, who was not involved in the family meeting, expressed concern that the decision to withdraw was being made too hastily & that it was being influenced by the decision to donate. She also made it clear that she was not comfortable with the role she was being asked to play in implementing the order. Questions for Discussion • What would you do if confronted with this case or asked your advice? • Is DCD acceptable ethically? If so, what ethical principles should guide our approach to DCD? • Would it be acceptable for the intensivist to opt out of participating in this case of DCD? 21 DCD Fast Facts • Definition: – Recovery & use of organs from pts declared dead using cardiopulmonary criteria • Who & what : – Pts who have a non-recoverable & irreversible neurological injury resulting in vent dependency but not fulfilling brain death criteria…Others may include those with endstage musculoskeletal disease, pulmonary disease, & high spinal cord injury – Most commonly kidneys & liver but also pancreas, lungs, &, in rare cases, heart • Process: – Pt/fam decision to w/d MV & other life-sustaining measures; request for organ donation – Usually pt moved from ICU to surgery with family saying “good-byes” prior to death – Extubation & w/d of other life-sustaining measures; meds given (e.g., Heparin) & perhaps advance placement of catheters in large arteries/veins to facilitate rapid infusion of organ-preservation solutions after death – Monitor for asystole (absence of sufficient cardiac activity to generate a pulse or blood flow, not necessarily absence of all electrocardiographic activity)…if occurs in required time (60 or 120 min), death declared by attending or designee after 2 or 5 min – Transplant team enters & begins organ retrieval process DCD in Perspective • DCD traditional approach to organ donation – Prior to 1970s all organ donation involved patients declared dead based on cardiopulmonary criteria – DCD all but abandoned in U.S. after brain death criteria widely adopted because transplant outcomes were better – With critical shortage of organs & longer waitlists, interest revived • 6,290 candidates died while awaiting organs in 2008 • Waiting List for Life has doubled in 10 years from 46,961 to 100,532 in 2009 DCD in Perspective (cont.) • DCD deemed ethically acceptable – Institute of Medicine (3 reports: ‘97, ‘00, ‘06), Canadian Council on Organ Donation & Transplantation’s National Forum, U.S. Consensus Conference, American Medical Association, & Society of Critical Care Medicine • TJC requirement: – LD.3.110 EP 12: Develop a donation policy that addresses opportunities for asystolic recovery, based on an organ potential for donation that is mutually agreed upon by the designated OPO, hospital, and medical staff. – The standard requires that relevant hospitals have policies in place, not allow the practice—can choose to opt out because of concerns about ethics, quality of end-of-life care, or other reasons 24 DCD in Perspective (cont.) • Still, ethical concerns abound—not from patients/families but among caregivers • Positive possibilities but… – Circumventing brain death criteria – Quality of donor organs – Co-mingling of decision to w/d & donate – Time requirement for declaring death too short – Pastoral concerns related to family – Similarities/slippery slope to euthanasia – Pre-mortem administration of anticoagulants 25 26 Ethical Criteria • Healthy degree of skepticism & suspicion acceptable – Different interests & motives among the various parties involved • Still, DCD can be done ethically if… Decision to withdraw separate from decision to donate Those requesting donation not involved in the direct care of patient True informed consent is obtained (patient or family) Patient not subjected to disproportionate risks for good of donation EoL (inc. palliative & pastoral) care of the patient not compromised Families given option of being present until death & viewing body after organ retrieval if desired – Death declared by qualified physician who is not member of transplant team – Staff allowed to opt out of participating in DCD if morally opposed – – – – – – Unresolved Ethical Question • Pre-mortem administration of Heparin – Initially, many OPO protocols did not require (1990s) – Some OPOs began incorporating at “therapeutic” levels (e.g., 80 units/kg or 5000 units/70kg not to exceed 10,000 units) – Now virtually all OPOs require at higher levels (e.g., 400 units/kg) • According to the 2005 IOM conference, providing Heparin at the time of w/d “is the current standard of care” because “the long-term survival of the transplanted organ may be at risk if thrombi impede circulation to the organ after reperfusion • Ethical concern: could the pre-mortem administration of Heparin cause or exacerbate bleeding in typical DCD candidate & as a result hasten death? Unresolved Question (cont.) • Seems unlikely pre-mortem administration of Heparin, even at high doses (e.g., 400 units/kg), causes harm to DCD donors or hastens their death, – But no empirical data to prove this (only anecdotal)…driven more by desire to improve transplant outcomes • Still, ethically pre-mortem administration of Heparin can be justified using the principle of double effect – Any harm caused would be morally acceptable as an unintended side effect caused by the action taken to bring about the good of organ preservation • Given uncertainty, is explicit & separate consent for the pre-mortem administration of Heparin required? – Some say “yes,” others say “no” – Not necessary if during the general consent process the risk of harm from the use of Heparin as well as from other measures taken that do not directly benefit the DCD donor are spelled out clearly to the patient &/or family/surrogate Principle of Double Effect Action two effects good evil morally justified? Four Conditions Must Be Met 1. 2. 3. 4. The act must be morally good or indifferent. One must intend the good & not the evil. The evil cannot be a means to achieve the good. There must be a proportionate reason. 30 Return to Case • In this case, it seems everything handled properly with exception of including intensivist in the family meeting • Ethical criteria, as best as we can tell, seem to have been addressed • Should accommodate intensivist if concern primarily that w/d not appropriate – What about if concerns over DCD itself? Additional Resources • For further guidance, refer to “Donation After Cardiac Death: System Guidelines for Policy Development” – Located on corporate ethics intranet site: http://my.ssmhc.com/SiteDirectory/corporateethic s/Pages/PoliciesandPositionStatements.aspx 32 Questions & Discussion Today’s presentation & handouts will be placed on both HS & St. Mary’s Intranet sites Next Grand Rounds: Thursday, September 2, 2010 “Treatment and Evaluation of Atypical GERD” John Hamilton, MD, Carl Sunby, MD & Timothy Shaw, MD