Introduction

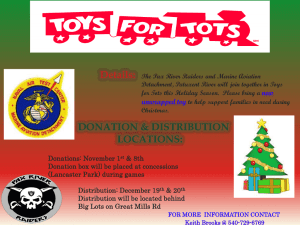

advertisement

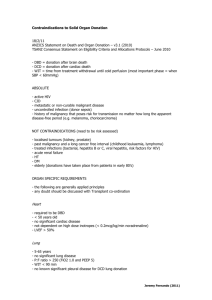

Donation after Cardiac Death System Guidelines for Policy Development Introduction SSM Health Care (SSMHC) has and will continue to support organ and tissue donation. Consistent with the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services (ERDs), we “encourage and provide the means whereby those who wish to do so may arrange for the donation of their organs and bodily tissue, for ethically legitimate purposes, so that they may be used for donation and research after death” (ERD 63). SSMHC is committed to treating seriously ill and dying patients holistically through medical interventions, palliative care, and psychosocial and spiritual services and to supporting their loved ones throughout the dying process. This same commitment extends to those who wish to donate their organs and tissues. While such donation is laudable, the care of the dying patient is paramount and will not be compromised in an effort to improve transplant outcomes. As of January 1, 2007, The Joint Commission has made it a requirement that hospitals have a protocol in place for Donation after Cardiac Death (DCD), that is, organ donation following withdraw of lifesustaining treatment resulting in the irreversible cessation of cardiopulmonary function. SSMHC operating entities are not required to provide this service but need to establish a policy that either allows (a) for the procurement of organs and tissues after cardiac death or (b) for the transfer of patients who wish to donate in this manner to facilities that provide it. These guidelines do not represent a detailed policy but only highlight areas of ethical concern that need to be integrated into DCD policies. SSMHC believes that DCD can be a morally permissible means of donating and obtaining organs and tissues when certain medical and ethical guidelines are established as part of a policy and adhered to in practice. Purpose These guidelines are intended to respect the wishes of patients who would like to donate their organs and tissues following irreversible cessation of cardiopulmonary function and to ensure that high quality, compassionate end of life care is always provided to them. The guidelines herein reflect SSMHC’s mission and values, Catholic identity, and commitment to caring for the dying and honoring personal values at the end of life. Patients who choose to donate as well as their loved ones must be treated with dignity throughout the dying and procurement processes. Such patients should not be reduced to their generous offer to donate. Palliative care should be provided with the same depth and quality as for all patients who have decided to withdraw life-sustaining treatment at the end of life. Approaching patients and/or their loved ones to consider DCD should be performed in a way that respects their dignity and does not manipulate or coerce them. 1. The Decision to Withdraw Life-Sustaining Treatment To ensure that DCD occurs in an ethically appropriate manner, the decision on the part of the patient or an appropriate surrogate to withdraw life-sustaining treatment that has been deemed non-beneficial and/or excessively burdensome should be made independently of the decision to donate organs and tissues. Once this decision has been made, the patient and/or loved ones can be approached about DCD by a qualified individual (see section below on “The Request for Donation”). Before the request for donation is made to the patient and/or loved ones, however, a second physician should examine the patient and concur that the patient is a candidate for DCD based on the most recent medical criteria for inclusion. This can help avoid wrongly identifying patients for DCD and falsely encouraging patients and loved ones about the possibility for donation. 2. The Request for Donation Federal regulations stipulate that those who approach families to make a request for organ donation must be either an Organ Procurement Organization (OPO) representative or a designated requestor from within the organization who has completed a course offered or approved by the OPO. SSMHC operating entities may choose to have either an OPO representative or an internal associate acting as a “designated requestor" approach the family to request donation. When a request for donation is made, an associate of SSMHC must be in the room as either the designated requestor or to offer 1 support, information, and/or services. The associate may be from either a clinical or non-clinical area. OPO representatives serving as requestors in SSMHC operating entities ought to be oriented to the mission, values, culture, spirituality, and palliative care commitments of the organization. 3. Informed Consent Donation and procurement of vital organs after death can only occur after informed consent is obtained from the patient (usually in the form of a written declaration such as is found in an advance directive or on the back of one’s driver’s license) and/or from an appropriate surrogate. Donation of organs is a deeply personal decision that strikes at the heart of the patient’s values and as such informed consent is required before every donation. Those seeking consent from the patient and/or family/surrogate should describe the process in easily understandable terms and explain all steps in the process and any measures that may be taken to ensure a successful transplant but will not benefit the patient (e.g., administration of Heparin pre-mortem). Only with this information can true informed consent be obtained. 4. Involvement of Critical Care and Palliative Care Services Critical and palliative care professionals provide treatment and comfort care to many dying patients in our entities. After consent to organ and tissue donation is made, therapies that are harmful to the dying patient should be avoided even if they might improve the chances of a successful organ transplant (see sections below on “Pain Management” and “Heparin”). If, in the delivery of high quality, compassionate end-of-life care, organ donation is possible, then critical care and palliative care professionals ought to work toward that outcome so that patients who wish to donate may do so. The palliative care service ought to attend to the dying patient and family throughout their stay. 5. Involvement of Spiritual Care Services Spiritual Care services should be considered an essential part of the care giving team that is assisting the patient and loved ones during the dying and procurement processes. These professionals can provide spiritual and religious support at appropriate times in the process (e.g., prayers for the dying at the time of withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, emotional and spiritual support for the family and for care giving staff). 6. Place of Death and Family Involvement After understanding the process of withdrawing life-sustaining treatment from the patient, loved ones ought to have the option of remaining with the patient until death is declared. It is the responsibility of each entity to accommodate loved ones wishing to remain with the patient. Ideally, death should occur in the intensive care unit because staff here is most skilled in this area and loved ones can more easily be present until the time of death. If this can be accomplished reasonably, loved ones should be informed of the need to move the patient quickly to surgery following death. 7. Pain Management Patients that have chosen to donate organs and tissue after death, should be kept as free of pain as possible so that they may die comfortably and with dignity (ERD 61). When withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, patients are to be treated with medications that prevent and alleviate pain and suffering. Medications are not to be given for the purpose of causing or hastening death. However, pain medications may be given to a dying person, even if they indirectly shorten the patient’s life so long as the intent is not to hasten death (ERD 61). 8. Heparin The use and amount of Heparin (or other anticoagulant medications) administered to potential DCD candidates pre-mortem remains a source of contention in the medical and ethical community. While it seems unlikely that the pre-mortem administration of Heparin, even when given at high doses (e.g., 400 units/kg), causes harm to DCD donors or hastens their death, no empirical data to date have been put forward to substantiate this claim, which is based largely on anecdotal evidence. Nevertheless, from an ethical perspective, the pre-mortem administration of Heparin can be justified in DCD settings using the principle of double effect, as any harm caused by the use of Heparin would be morally acceptable as an 2 unintended side effect caused by the action taken to bring about the good of organ preservation. Explicit and separate consent for the pre-mortem administration of Heparin is not required. However, during the consent process the risk of harm from the use of Heparin as well as from other measures taken that do not directly benefit the DCD donor need to spelled out clearly to the patient and/or family/surrogate (see #3 above). 9. Declaration of Death Death under DCD protocols must be certified using standardized, objective, and audible criteria and must follow applicable state and federal law. To avoid any potential conflicts of interest, death should be declared by the attending physician or attending designee and never by a member of the organ procurement team. 10. Viewing Patient after Organ Procurement Each entity ought to provide a viewing area for loved ones who express a desire to view the patient’s body after organ procurement. Every effort should be made to ensure that the patient is suitable for viewing. 11. Caring for Patients and Families after Unsuccessful Attempt to Donate Patients that do not die within the allotted time following withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (this may vary depending on OPO protocols for DCD) are not suitable to donate organs. These patients will be taken to a private and comfortable room and rejoined with their loved ones. Each entity should ensure that every effort is made to provide excellent comfort care and spiritual support in this very difficult situation. Loved ones should be alerted during the consent process that this is a possibility and that the overall care of the patient will not be compromised. 12. Conscientious Objection Each entity should allow for individual staff members who oppose DCD to opt out of taking part in the protocol. Given that these situations are rarely emergent, reasonable accommodations can usually be made. Patient care, however, ought to never be compromised in an attempt to honor the employee’s wishes. 3