Phillip human mate preference

advertisement

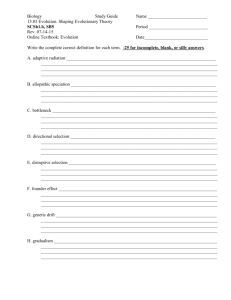

Phillip Skaliy Genetics Ely November 4, 2011 Human Mate Preference: Genetic and Social/Environmental Influences Creatures and animals across the world do not prefer all members of the opposite sex equally. Some research has been done in this area, but it is extremely hard to figure out the entire story about mate selection due to the fact that many different systems and thought processes control it. Mate choice is very important to an organism’s success and the success of its family and species due to the fact that the genes of the parent are eventually passed down to the children. Thus, someone will want to mate with a person who has “good genes” because those genes are eventually inherited by the offspring. One would assume that organisms, including humans, take this decision of who to mate with seriously because not only does it have major impacts on their descendents but also because humans want to mate with individuals of certain characteristics that meet their specific needs. Therefore, not only are the interests of the children involved, but also there are some personal interests involved with mate choice. When it comes to these personal interests, most people would like to mate with successful, intelligent, and attractive people. But certain questions arise, like which of these traits is most influential and what happens when one compares long-term relationships to short-term relationships? Many other questions surround this topic, like which genes code for what characteristics dealing with mate choice, and what other non-genetic factors influence mate choice. Another question could be if someone would be inclined to mate with a person of a more diverse genotype due to the fact that diverse genotypes tend to lead to healthier children, and how would someone recognize a different genotype than their own. These types of questions are important, and most have been answered at least partially by many different scientists around the world. Ultimately, recent research has found that there is more of a genetic component to mate choice than was thought in the past, but there are still some environmental, social, and familial influences to mate choice that cannot be ignored. One non-genetic influence that many people can relate to with regards to mate choice is that of the parents (Zietsch et al. 2011). Family influence on mate preference in past societies has been proven through anthropological evidence, and it has shown that parents throughout history and throughout many different cultures have significantly influenced mate choice with regards to income and age (Buunk et al. 2008). To test whether this hypothesis was actually true, Zietsch et al. (2011) conducted a twin study and compared the spouses of female twins to see if those spouses correlated significantly on income and age, along with a variety of other factors. The results showing the correlations between twin pair partners for age and income can be seen in table one. As one can see, the correlations between spouses of female twins for income and age are fairly strong and very significant, especially when compared to other traits (Table 1, the other traits are not shown due to the size restriction of this page). On top of that, the correlation is strong between spouses of monozygotic (or identical) female twins and spouses of dizygotic (or fraternal) female twins, showing that this outside pressure is a family influence and not a genetic influence. If this was a genetic influence, then the influence would be much greater when comparing spouses of identical twins because monozygotic twins share the same genome. Zietsch et al. (2011) hypothesized that parents have an evolutionary interest in ensuring that their daughters mate with older and higher income men. Parents often want to ensure that their daughters live a comfortable lifestyle, and marrying a successful man is a good way in making sure that happens. Thus, when looking at mate preference for females, it seems that females tend to stress the income and age of their mates, which is why income and age are two of the most important and most studied traits of a man by researchers today. Table 1. Correlations between twin pair partners (i.e., twin pair correlations for mate choice), uncorrected and corrected for assortative mating Mate choice Raw data: MZF MZM DZF DZM DZOS Controlling for assortative mating: MZF MZM DZF DZM DZOS Income Age .30 (.04)** .12 (.06) .37 (.05)** .24 (.08)* .06 (.06) .93 (.01)** .92 (.02)** .90 (.02)** .92 (.03)** .90 (.02)** .24 (.05)** .07 (.06) .30 (.06)** .21 (.09) −.09 (.07) .19 (.03)** .09 (.06) .18 (.05)** −.02 (.04) .00 (.07) Note. Values in parentheses are standard deviations, except where indicated. “Overall” correlations (and 95% CIs) are estimated by constraining twin correlations to be equal across all traits (except for age in the raw data). MZF = monozygotic female pairs, MZM = monozygotic male pairs, DZF = dizygotic female pairs, DZM = monozygotic male pairs, DZOS = dizygotic opposite-sex pairs. * Significant at P < .01, ** Significant at P < .001 Another hypothesis involving parents and their influence on mate choice is the sexual imprinting hypothesis. Sexual imprinting is the process by which individuals acquire mate-choice criteria during development by using their opposite-sex parent as the template of a desirable mate. So, for example, a man would search for a woman like his mother. In past studies, sexual imprinting has been seen in less advanced animals, but its role in humans is not very clear (Oetting et al. 1995). This study compared the similarity between a person’s spouse and his or her opposite sex parent, relative to other family members (Table 2) (Zietsch et al. 2011)). It is clear that twins’ partners were not more similar in any trait to the twins’ opposite-sex parent than to the twins’ same-sex parent. In fact, twins’ spouses were much more similar to the twin and co-twin than the twin's opposite-sex parent. Thus, parents have an influence on who their children marry when it comes to income and age, but there was no evidence that they serve as a template for the future mate of their child .. Since other studies have found evidence of sexual imprinting Bereczkei et al. (2004), more work needs to be done in this area to resolve the conflicting results. Zietsch et al. (2011) suggest that maybe different traits should be considered than the ones that were tested in this experiment and see whether the results change. Another suggestion was to compare newlyweds to older couples and see if there are any environmental and genetic differences between the couples. Pawlowski et al. (1999) examined how market value affected a person’s selection of mate. The term market value simply means how appealing someone appears to the opposite sex in a competitive market. Market value is dependent on many different characteristics, but one characteristic that is especially important is age. After examining personal advertisements in newspapers, Pawlowski et al. decided to observe if there was a correlation between age and market value and whether people with a greater market value were more demanding when searching for partners. The data indicated that the optimum age for females was between twenty and thirty years old which correlates with their maximum fecundity and reproductive value. Thus, one could infer that males put high importance on child rearing. For men, the age at which they had the best market value was between thirty and forty years old. Pawlowski and Dunbar proposed that male market value is attributed mostly to income and commitment to the relationship, meaning that the male will not get a divorce or die over the next twenty years. Twenty years is the optimum amount of commitment time for a woman when looking for a mate because that is about how long it takes to raise a child,. Ultimately the idea is that women often view older men as safer, better behaved, and wiser than younger guys, so they are more prone to have a relationship with them because they are a safer choice. Pawlowski and Dunbar also compared market value and the number of traits that person sought in a mate, and the researchers found a correlation between a high market and the number of traits they sought in their partner. This observation suggests that people of high market value impose strong demands in their mate search criteria, and the opposite is true for people of low market value. It seems that mate choice is very complex and is almost like a negotiation in the way that people stress some traits over others. Overall, it may seem surprising that people are waiting somewhat later in life to enter into relationships and have children, but Pawlowski and Dunbar (1999) explain that when someone considers the amount of money that it costs to raise a child, it is not surprising that people would have smaller family sizes and wait until later in life to have their children. Another important factor in mate choice is intelligence. It seems that as intelligence increases, that would make a mate more highly valued. Most likely, that intelligent person would be more successful and have more access to essential resources, especially for child rearing. Studies have already shown that intelligence seems to be a necessity and not a luxury in mates (Li et al. 2002). There is also evidence now to suggest that intelligence could be a fitness factor, meaning that it could be beneficial to conceive children with more intelligent mates (Miller 2000). Prokosch et al. (2009) hypothesized that women would prefer men with higher intelligence and also higher creativity, a trait closely related to intelligence, in both long and short term relationships. They also studied whether preferences for intelligence and creativity shifted across the menstrual cycle. If intelligence or creativity cues men with good quality genes, then these characteristics should become especially important during the menstrual cycle of a female in short-term relationships. In order to assess intelligence, the men took a test and participated in videotaped interviews. These videos would be shown to the women, and they would decide for themselves whether the person was intelligent or not. This process is called perceived intelligence. The study found that there was some variability, but overall, in both long and short-term relationships, women preferred men of higher intelligence. But, picking mates on perceived intelligence seemed to be more inaccurate than when compared to intelligence measured form the test. Women also preferred more creative men. The researchers believe that women stress intelligence because of financial security and dependability. The researchers also hypothesized that intelligence was important because intelligence shows that someone has “good genes,” but there was not a shift in importance for intelligence while the women were menstruating. Therefore, it is not certain whether intelligence is an indicator of good genes according to this study. This study also suggested that further investigation needed to occur in order to test whether creativity is more related to physical attractiveness or intelligence. Overall, it seems as though women appear to prefer more intelligent men, but more research needs to be done in order to more clearly understand what effect intelligence has on mate choice (Prokosch et al 2009). All of the factors that have been described up to this point are mainly nongenetic factors. That means that these factors are external influences with very little genetic basis, or these are characteristics that are specifically and consciously looked for in a mate. But there has been some evidence that mate choice is not only just a product of environmental factors but also genetic ones as well (Lie et al. 2010). The Major Histocompatibility Complex (or MHC) is found in all jawed vertebrates and contains genes that are essential for many biological functions, like the immune system (Doherty et al. 1975)and mate preference (Millinski 2006). MHC alleles are expressed co-dominantly, meaning that increasing the diversity at the MHC should be beneficial for biological systems like the immune system because that organism will be better able to defend itself from more foreign pathogens (Doherty et al. 1975). How the MHC influences mate choice is debatable, but most researchers seem to think that heterozygosity at the MHC is most preferred when looking for a mate (Carrington et al. 1999). One of the main hypotheses surrounding the MHC is the disassortative mating hypothesis, which suggests individuals prefer mates with different MHC alleles to avoid inbreeding and gain indirect benefits like their offspring being more resistant to disease (Brown 1997). Similarly, Brown (1997) proposed the good-genes-as-heterozygosity hypothesis, which states that preferences for MHC diverse mates are desired because that will most likely enhance the genetic diversity of the offspring, making them more fit and better able to survive. Past experiments (Mitton et al. 1993, Roberts et al. 2005) have proven that many different animals prefer mates of dissimilar and diverse Major Histocompatibility Complexes, but the exact effect in humans is not very clear. Lie et al. (2010)investigated whether MHC diversity and dissimilarity affected face preference when searching for a mate in short and long-term relationships. When someone looks at another person’s face, something in that face intuitively triggers that person to know that he or she is looking at a person with a genetically different MHC than his or her own. Therefore, Lie et al. (2010) expected that people would prefer to mate with people who had diverse Major Histocompatibility Complexes in long and short-term relationships. The results of this experiment clearly showed that males prefer the faces of MHC dissimilar females in both the short-term and long-term. This result was not the same for females though. Some people might refute this claim of genetic facial dissimilarity between partners because it has been shown in past experiments that couples look more similar than just by chance alone (Hinsz 1989, Little et al. 2006). Lie et al. (2010) suggests that these similar facial characteristics between mates according to this other experiment might be controlled by environmental influences and not have a genetic basis. Therefore, it is possible that facial characteristics can be controlled by genetic influences and environmental influences at the same time. An important question to ask is why males would seek genetically dissimilar females to mate with. One answer to that question is that a male’s reproductive success is heavily dependent on the health and fertility of the female (Buss and Schmidt 1993). Thus, males should value fertility in their partners, and MHC dissimilarity may serve to reduce fertility problems that are associated with MHC allele sharing, which include spontaneous birth abortion and longer birth intervals (Beydon et al. 2205, Ober 1999, Ober et al. 1992, Ober et al. 1998, see also Knapp et al 1996). Another question might be why males were more sensitive to recognizing female facial MHC dissimilarity than females were, and it seems that males put an emphasis on visual aspects of their mates while females put an emphasis on odor aspects of their mates. Therefore, it would be easier for a male to detect facial MHC dissimilarity (Havlicek et al. 2008, Herz et al. 2002). For genetic diversity, females preferred MHC diversity in both short-term and long-term mates (Lie et al. 20120). This makes sense because heterozygosity is heritable and choosing a MHC diverse mate is associated with fitness, meaning the mate can provide resources in the short-run and parental care in the long run. Males showed no preference for MHC diversity. Overall, this study about the Major Histocompatibility Complex only tested mate preference and not actual mate selection. Therefore, this experiment needs to be supplemented with how mate preference ultimately leads to mate selection. As discussed earlier, some people have a greater market value, and that allows them to be choosier when selecting a mate. Maybe this theory is the same when one considers genetic influences, and studying that relationship would be an interesting experiment and lead to useful results. Also, this study is just one of many experiments covering the Major Histocompatibility Complex. Other tests have been done on facial attractiveness and odor (Roberts et al. 2008, Thornhill et al. 2003), and all these results seem to conflict each other in some way. Therefore, more research needs to be done in this area before researchers can consistently say how the MHC controls mate choice. But, ultimately, these results do show that the MHC does have some control and influence on mate selection, and that females and males both experience it in some way when dealing with facial characteristics (Lie et al 2010). In the end, mate choice is one of many examples of a human trait or action that is controlled by both environmental and genetic factors. This is significant because it is not only our genes that influence the way someone looks and acts, but it is also controlled by environmental factors like how someone was raised by their parents. Therefore, issues like mate choice are extremely hard to study and fully understand because there are many different influences that can affect it. In order to understand mate choice completely, future studies will have to be done to see exactly what genetic and environmental influences affect mate choice and how those influences interact with each other. Bibliography Bereczkei, T., G. Hegedus, and G. Hajnal. 2009. Facialmetric similarities mediate mate choice: sexual imprinting on opposite-sex parents (retraction of vol 276, pg 91, 2009). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 276:1199. Beydon, H., A.F. Saftlas, Association of human leucocyte antigen sharing with recurrent spontaneous abortions. Tissue Antigens, 65 (2005), pp. 123–135. Brown, L. A theory of mate choice based on heterozygosity. Behavioral Ecology, 8 1 (1997), pp. 60–65 Buss, D.M., D.P. Schmitt. Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100 (1993), pp. 204–232. Buunk, A. P., J.H. Park, S.L. Dubbs, 2008. Parent-offspring conflict in mate preferences. Review of General Psychology 12:47–62. Carrington, M., G.W. Nelson, M.P. Martin, T. Kissner, D. Vlahov and J.J. Goedert, et al. HLA and HIV-1: heterozygote advantage and B*35-Cw*04 disadvantage. Science, 283 5408 (1999), pp. 1748–1752. Doherty, P.C., R.M. Zinkernagel, Enhanced immunological surveillance in mice heterozygous at the H-2 gene complex. Nature, 256 5512 (1975), pp. 50–52. Havlicek, J., T. Saxton, S.C. Roberts, E. Jozifkova, S. Lhota, J. Valentova and J. Flegr, He sees, she smells? Male and female reports of sensory reliance in mate choice and non-mate choice contexts. Personality and Individual Differences, 45 6 (2008), pp. 565–570. Herz, R.S., M. Inzlicht, Sex differences in response to physical and social factors involved in human mate selection—The importance of smell for women. Evolution & Human Behavior, 23 (2002), pp. 359–364. Hinsz, V.B., Facial resemblance in engaged and married couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 6 (1989), pp. 223–229. Knapp, L.A., J.C. Ha and G.P. Sackett, Parental MHC antigen sharing and pregnancy wastage in captive pigtailed macaques. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 32 1 (1996), pp. 73–88. Li, N.P., J.M. Bailey, D.T. Kenrick and J.A.W. Linsenmeier, The necessities and luxuries of mate preferences: Testing the tradeoffs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82 6 (2002), pp. 947–955. Lie, H. L.W. Simmons, and G. Rhodes. "Genetic Dissimilarity, Genetic Diversity, and Mate Preferences in Humans." Evolution and Human Behavior 31.1 (2010): 48-58. Little, A.C., D.M. Burt and D.I. Perrett, Assortative mating for perceived facial personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 40 (2006), pp. 973–984. Miller, G.F. Sexual selection for indicators of intelligence, G. Bock, J.A. Goode, K. Webb, Editors , The nature of intelligence, Wiley, New York (2000), pp. 260–270 (Novartis Foundation Symposium 233). Milinski, M. The major histocompatibility complex (MHC), sexual selection and mate choice. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 37 (2006), pp. 159– 186. Mitton, J.B., W.S.F. Schuster, E.G. Cothran and J.C. De Fries, Correlation between the individual heterozygosity of parents and their offspring. Heredity, 71 (1993), pp. 59–63 Ober, C. Studies of HLA, fertility and mate choice in a human isolate. Human Reproduction Update, 5 (1999), pp. 103–107. Ober, C., S. Elias, D. Kostyu and W.W. Hauck, Decreased fecundability in Hutterite couples sharing HLA-DR. American Journal of Human Genetics, 50 (1992), pp. 6–14. Ober, C., T. Hyslop, S. Elias, L.R. Weitkamp and W.W. Hauck, Human leukocyte antigen matching and fetal loss: Results of a 10 year prospective study. Human Reproduction, 13 1 (1998), pp. 33–38. Oetting, S., E. Prove, and H. J. Bischof. 1995. Sexual imprinting as a two-stage process: mechanisms of information storage and stabilization. Animal Behaviour 50:393– 403. Pawlowski, B., and R.I.M. Dunbar. "Impact of Market Value on Human Mate Choice Decisions." Proceedings: Biological Sciences 266 (1999): 281-85. Prokosch, Mark D., Richard G. Coss, Joanna E. Scheilb, and Shelley A. Blozis. "Intelligence and Mate Choice: Intelligent Men Are Always Appealing." Evolution and Human Behavior 30.1 (2009): 11-20. Roberts, S.C., L.M. Gosling, V. Carter and M. Petrie, MHC-correlated odour preferences in humans and the use of oral contraceptives. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences, 275 (2008), pp. 2715–2722. Roberts, S.C., A.C. Little, L.M. Gosling, B.C. Jones, D.I. Perrett and V. Carter, et al. MHC-assortative facial preferences in humans. Biology Letters, 1 4 (2005), pp. 400– 403. Thornhill, R., S.W. Gangestad, R.D. Miller, G.J. Scheyd, J.K. McCollough and M. Franklin, Major histocompatibility complex genes, symmetry, and body scent attractiveness in men and women. Behavioral Ecology, 14 5 (2003), pp. 668–678. Zietsch, B.P., K. Verweij, A.C. Heath, and N.G. Martin. "Variation in Human Mate Choice: Simultaneously Investigating Heritability, Parental Influence, Sexual Imprinting, and Assortative Mating." The American Naturalist 177 (2011): 605-16.