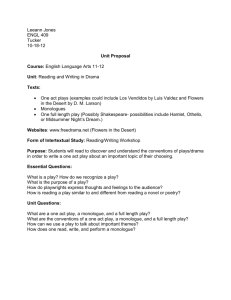

Monologues

advertisement

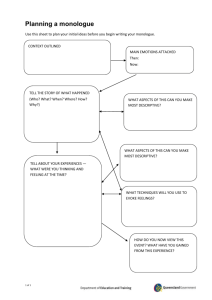

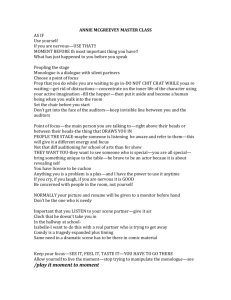

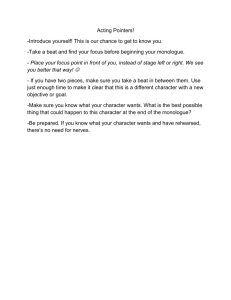

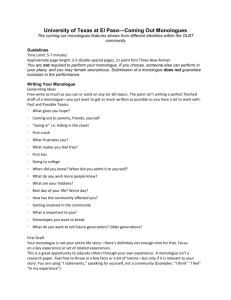

Monologues and Soliloquies A monologue is an extended uninterrupted speech by a single person. It is common in both drama and written fiction When the speech is directed to another person/people, it is called a monologue When the speech is directed to the person him/herself it is called a soliloquy Other types of monologues include Dramatic Monologues (usually poetry) Stand-up comedy (think Jay Leno at the beginning of the tonight show) Certain songs in musical theatre (when they reveal the characters thoughts) Villain Speeches (think Joker, Grinch) Rants (a la Rick Mercer) Monologue speech by a single character Expresses thoughts and ideas Addresses another character or the audience Soliloquy speaks to himself/herself relating thoughts and feelings sharing them with the audience. other characters, however, are not aware of what is being said. A monologue...is when the character may be speaking his or her thoughts aloud, directly addressing another character...It is distinct from a soliloquy, which is where a character relates his or her thoughts and feelings to him/herself and to the audience without addressing any of the other characters. HOW TO READ A MONOLOGUE Break the monologue into sections and work on transitioning between sections. Memorize your monologue. Practice it over and over again. Practice it for someone else. Make adjustments based on their feedback Use a prop if appropriate but make sure it doesn’t take away from your speech Project your voice in the space. Block out your audience, but make sure they can hear you. Act as if your surroundings are real and really there. Ex: if you are supposed to be watching someone, “track” them with your eyes, even if they are actually invisible. Move around as appropriate. Don’t just stand there in one spot. Willy often has "internal monologues" where he imagines he is talking, most often, with his brother Ben. Seen by Willie to as a highly successful man, mining diamonds in Africa and buying large tracts of open land, Willy carries on his conversations, or monologues, with his brother, who is now deceased. Willy's discussions are not truly directed to himself or the audience, but to another character, even if imaginary; he carries on entire conversations, providing both sides of the discussion. So these are not soliloquies. LINDA: Are they any worse than his sons? When he brought them business, when he was young, they were glad to see him. But now his old friends, the old buyers that loved him so and al- ways found some order to hand him in a pinch — they’re all dead, retired. He used to be able to make six, seven calls a day in Boston. Now he takes his valises out of the car and puts them back and takes them out again and he’s exhausted. In- stead of walking he talks now. He drives seven hundred miles, and when he gets there no one knows him any more, no one welcomes him. And what goes through a man’s mind, driving seven hundred miles home without having earned a cent? Why shouldn’t he talk to himself? Why? When he has to go to Char- ley and borrow fifty dollars a week and pretend to me that it’s his pay? How long can that go on? How long? You see what I’m sitting here and waiting for? And you tell me he has no character? The man who never worked a day but for your benefit? When does he get the medal for that? Is this his reward — to turn around at the age of sixty-three and find his sons, who he loved better than his life, one a philandering bum...