Precipitation Reactions

advertisement

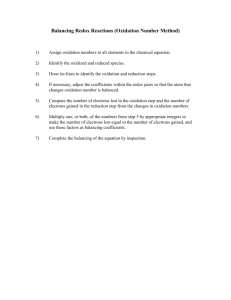

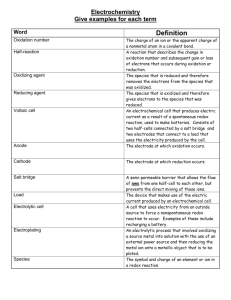

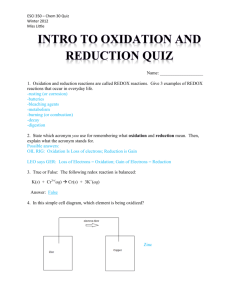

Why do reactions occur at all? • The driving force of all reactions is related to energy • The driving force is not “make everything achieve its lowest possible energy,” although that often happens • The driving force is not “increase the entropy of the system,” although that often happens. • We use a bookkeeping technique called “free energy” to calculate the driving force of all reactions. Wait until chapter eight Types of Reactions (I) • Precipitation Reactions: A process in which an insoluble solid precipitate drops out of the solution. • Most precipitation reactions occur when the anions and cations of two ionic compounds change partners. Pb(NO3)2(aq) + 2 KI(aq) 2 KNO3(aq) + PbI2(s) Types of Reactions (I) • Acid–Base Neutralization: A process in which an acid reacts with a base to yield water plus an ionic compound called a salt. • The driving force of this reaction is the formation of the stable water molecule. HCl(aq) + NaOH(aq) NaCl(aq) + H2O(l) Types of Reactions (I) • Oxidation–Reduction (Redox) Reaction: A process in which one or more electrons are transferred between reaction partners. • The driving force of this reaction is the decrease in electrical potential. Mg(s) + I2(g) MgI2(s) Types of Reactions (II) Double Exchange • Metathesis Reactions: These are reactions where two reactants just exchange parts. AX + BY AY + BX HNO3(aq) + KOH(aq) KNO3(aq) + HOH(l) BaCl2(aq) + K2SO4(aq) BaSO4(s) + 2 KCl(aq) Types of Reactions (II) • Single Exchange Reactions: These are reactions where one reactants switches place with a partnered reactant. A + BY AY + B 3 C(s) + 2 Fe2O3(s) 4 Fe(s) + 3 CO2(g) Types of Reactions (II) • Combination Reactions: These are reactions where two parts come together. A + B AB H2O(g) + SO3(g) H2SO4(aq) Types of Reactions (II) • Decomposition Reactions: These are reactions where a large molecule falls apart. AB A + B NH4NO2(s) N2(g) + 2 H2O(g) Electrolytes • Electrolytes: Dissolve in water to produce ionic solutions. • Nonelectrolytes: Do not form ions when they dissolve in water. Electrolytes • Why do ionic compounds conduct electricity when molecular ones generally do not? Electrolytes • Strong Electrolyte: Total dissociation when dissolved in water. • Weak Electrolyte: Partial dissociation when dissolved in water. Electrolytes Calculating Electrolyte Concentrations • At this point, to calculate electrolyte concentration we must assume 100% of the ions dissociate • Be sure to account for the number of ions in one formula unit when calculating ion concentrations 3 ions from 1 formula unit For example: H 2O CaClO4 2 s Ca 2 aq 2 ClO4 aq Chemical Equations • Three basic equations are used for reactions: – Molecular Equation: All reactants and products are written in molecular form. – Ionic Equation: All dissolved strong electrolytes are written as the dissociated ions. – Net Ionic Equation: All ions that are identical on both sides are deleted. Chemical Equations • Molecular Equation: All reactants and products are written in molecular (non-dissociated) form along with their phases. – Pb(NO3)2(aq) + 2 KCl(aq) PbCl2(s) + 2 KNO3(aq) – 2 HCl(aq) + Cu(OH)2(s) CuCl2(aq) + 2 HOH(l) – C2H3O2H(aq) + KOH(aq) KC2H3O2(aq) + HOH(l) Chemical Equations • Ionic Equation: All dissolved strong electrolytes in the molecular equation are broken into their ions. – Pb2+ + 2 NO3– + 2 K+ + 2 Cl– PbCl2(s) + 2 K+ + 2 NO3– – 2 H+ + 2 Cl– + Cu(OH)2(s) Cu2+ + 2 Cl– + 2 HOH(l) – C2H3O2H(aq) + K+ + OH– K+ + C2H3O2– + HOH(l) Chemical Equations • Net Ionic Equation: Spectator ions that occur on both sides are cancelled to give only those species which undergo change. – Pb2+ + 2 Cl– PbCl2(s) – 2 H+ + Cu(OH)2(s) Cu2+ + 2 HOH(l) – C2H3O2H(aq) + OH– C2H3O2– + HOH(l) Solubility • Solubility is not really an “on-off switch”, but rather a continuum • A compound is soluble if it can make a 0.01 M solution. • Many things can affect solubility: temperature, pressure, presence of other solutes, etc. Precipitation Reactions: Solubility Rules • Rules are not a complete set, but still pretty good • Lower numbered rules take precedence over higher-numbered rules Precipitation Reactions: Solubility Rules 1. All compounds of the alkali metals and ammonium are soluble 2. All nitrates, nitrites, perchlorates, chlorates, acetates, and hydrogen carbonates are soluble. 3. All chlorides, bromides, and iodides are soluble except with silver(I), lead(II) and Hg22+. 4. All sulfates are soluble except with lead(II), Hg22+, and alkali earths below magnesium. 5. All oxides and hydroxides are insoluble except with alkali earths below magnesium. 6. All phosphates, carbonates, sulfites, and sulfides are insoluble. The ions chart is on p.57 Precipitation Reactions: Thinking synthetically •A precipitation reaction demands that both reactants start as soluble compounds. •A precipitation reaction demands that at least one product ends as an insoluble compound. •Precipitation reactions are one way to synthesize insoluble salts. The ions chart is on p.61 Synthesizing an insoluble salt AB(aq) + CD(aq) AD(aq) + CB(s) •C must be insoluble with B but soluble with D. •B must be soluble with A but insoluble with C. •A must be soluble with both B and D. •D must be soluble with both C and A. Synthetic thinking is generally easier when you start with the names and then work to the formulas. What would be good choices for A and D? The ions chart is on p.57 Acid-Base Reactions • Arrhenius Acid: • A substance which dissociates to form hydrogen ions (H+) in solution. Acid-Base Reactions • Arrhenius Base: • A substance that dissociates in, or reacts with, water to form hydroxide ions (OH–). Acid-Base Reactions • Arrhenius Acid: • Arrhenius Base: • A substance that dissociates in, or • A substance which dissociates to reacts with, water form hydrogen ions (H+) to form hydroxide in solution. ions (OH–). • This H+ ion attaches to water and forms a hydronium ion (H3O+). • In general, this means metal • In general, this means any anion hydroxides. with hydrogens attached as cations. Acid-Base Reactions • Brønsted Acid: Can donate protons (H+) to another substance in solution. • Brønsted Base: Can accept protons (H+) from another substance in solution. Acid-Base Reactions: Which hydrogens? The only hydrogens which can behave acidically (that is, dissociate as a H+ ion) are hydrogens written as if they were cations. Acetic acid (or hydrogen acetate): HC2H3O2 Acidic Not acidic Acid-Base Reactions: Polyprotic Acids •Anions with a negative charge grater than -1 require more than one acidic hydrogen to form a neutral compound (acid). •These acids are called polyprotic (diprotic, triprotic, et cet.) •It is possible to remove only one of the multiple acidic hydrogens. In that case, the created anion is itself acidic. Acid-Base Reactions Acid-Base Reactions • Neutralization Reaction: produces salt & water. – HA(aq) + MOH(aq) H2O(l) + MA(aq) • Write ionic and net ionic equations for the following: – (a) Ca(OH)2(aq) + 2 HC2H3O2(aq) – (b) HBr(aq) + Ba(OH)2(aq) – (c) HCl(aq) + NH3(aq) Acid-Base Reactions: Thinking synthetically •Acid-base neutralization reactions are good methods to create solutions of soluble salts. •The cation of the salt is the metal in the metal hydroxide (base). •The anion of the salt is the anion of the acid. •The driving force of this reaction is so strong that the base can be insoluble and the reaction still works. 2 HClO4 aq FeOH 2 s FeClO4 2 aq 2 H 2Ol As before, it is easier to start with the name and then go to the formulas. Acid-Base Reactions: Polyprotic Acids •Anions with a negative charge grater than -1 require more than one acidic hydrogen to form a neutral compound (acid). •These acids are called polyprotic (diprotic, triprotic, et cet.) •It is possible to remove only one of the multiple acidic hydrogens. In that case, the created anion is itself acidic. Sulfuric acid sulfate H 2 SO4 aq H aq HSO H SO 4 Hydrogen sulfate 2 4 Acid-Base Reactions •Strong acids and strong bases are strong electrolytes. They completely dissociate in water. •Weak acids and bases only partially dissociate in water. But an acid-base neutralization reaction will drive them to completely dissociate during the reaction. Oxidation Numbers Assigning Oxidation Numbers: All atoms have an “oxidation number” regardless of whether it carries an ionic charge. 1. An atom in its elemental state has an oxidation number of zero. 2. An atom in a monatomic ion has an oxidation number identical to its charge. Oxidation Numbers • Assigning Oxidation Numbers: All atoms have an “oxidation number” regardless of whether it carries an ionic charge. 1. An atom in its elemental state has an oxidation number of zero. 2. An atom in a monatomic ion has an oxidation number identical to its charge. Oxidation Numbers 3. An atom in a polyatomic ion or in a molecular compound usually has the same oxidation number it would have if it were a monatomic ion. –A. Hydrogen can be either +1 or –1. –B. Oxygen usually has an oxidation number of –2. •In peroxides, oxygen is –1. –C. Halogens usually have an oxidation number of –1. •When bonded to oxygen, (chlorine, bromine, and iodine) have positive oxidation numbers. Oxidation Numbers 4. The sum of the oxidation numbers must be zero for a neutral compound and must be equal to the net charge for a polyatomic ion. –A. H2SO4 – –B. ClO4– – 2(+1) + (?) + 4(–2) = 0 net charge ? = 0 – 2(+1) – 4(–2) = +6 (?) + 4(–2) = –1 net charge ? = –1 – 4(–2) = +7 That is, there is often one element in a compound that does not have an oxidation number determined from rules 1-3. You use this rule to figure out that element’s oxidation number. Identifying Redox Reactions Identifying redox reactions systematically is simple, but time-consuming: 1. Assign oxidation numbers for all atoms in a reaction 2. Determine if any element’s oxidation number has changed. Remember that there must be both oxidation and reduction in the same reaction. If you find only one, you are wrongety-wrong-wrong. Activity Series •The more active the metal, the higher up it appears on this list. •A more active metal is able to force its electrons onto a less active metal’s cation, thus forcing it out of solution. •That is, an active metal is a good reducing agent. •The two half-reactions “happen clockwise.” Activity Series • Activity series looks at the relative reactivity of a free metal with an aqueous cation. – Fe(s) + Cu2+(aq) Fe2+(aq) + Cu(s) – Zn(s) + Cu2+(aq) Zn2+(aq) + Cu(s) – Cu(s) + 2 Ag+(aq) 2 Ag(s) + Cu2+(aq) – Mg(s) + 2 H+(aq) Mg2+(aq) + H2(g) Activity Series Given the following three reactions, determine the activity series for Cu, Zn, & Fe. Fe(s) + Cu2+(aq) Fe2+(aq) + Cu(s) Zn(s) + Cu2+(aq) Zn2+(aq) + Cu(s) Fe(s) + Zn2+(aq) NR Activity Series – Thinking Synthetically • The activity series provides a new route towards making solutions of soluble salts, and a route toward making pure elemental metals. Example: How could we synthesize a solution of aluminum chlorate? Start with a solution of metal chlorate (where the metal is less active than aluminum) and then add an aluminum ingot. Al(s) + Ni(ClO3)2(aq) Al(ClO3)3(aq) + Ni(s) And then balance the reaction. In actual practice, the pressure, temperature, and concentration conditions matter a great deal. Balancing Redox Equations: The Challenge The correctly balanced redox equation is: 5 Fe2 MnO4 8 H 5 Fe3 Mn 2 4 H 2O This redox equation is incorrectly balanced: 2 4 2 Fe MnO 8 H 2 Fe3 Mn 2 4 H 2O Both versions are balanced for mass, but only one has the charge balanced on both sides. The rules we are about to develop exist so that we have a technique that balances both mass and charge. Balancing Redox: Oxidation Number Method Balancing Redox: Oxidation Number Method 2 7 Cr2O I 3 Cr IO3 Balancing Redox: Oxidation Number Method 2 7 Cr2O I 3 2 Cr IO 3 Balancing Redox: Oxidation Number Method +6 -2 -1 Cr2O72 I 2 Cr3 IO3 +3 +5 -2 Balancing Redox: Oxidation Number Method +6 -2 -1 Cr2O72 I 2 Cr3 IO3 +3 +5 Reduction: -6 Oxidation: +6 -2 Balancing Redox: Oxidation Number Method +6 -2 -1 Cr2O72 I 2 Cr3 IO3 +3 +5 -2 32 61 So we leave it untouched Balancing Redox: Oxidation Number Method 2 7 Cr2O I 8 H 3 2 Cr IO3 4 H 2O Balancing Redox: Oxidation Number Method 2 7 Cr2O I 8 H 3 2 Cr IO3 4 H 2O 2 7 1 8 +5 Cr O I H +/- 2 7 1 8 +5 Balancing Redox: ½ reaction method Balancing Redox: ½ reaction method 2 7 Cr2O I 3 Cr IO3 Balancing Redox: ½ reaction method Cr2O72 Cr 3 I IO3 Balancing Redox: ½ reaction method Cr2O72 2 Cr 3 I IO3 Balancing Redox: ½ reaction method Cr2O72 14 H 2 Cr3 7 H 2O I 3 H 2O IO3 6 H Balancing Redox: ½ reaction method Cr2O72 14 H 6 e 2 Cr3 7 H 2O I 3 H 2O IO3 6 H 6 e Balancing Redox: ½ reaction method Matt will write out this step; ain’t enough space here to do it justice. Balancing Redox: Conditions The rules you just learned assume that the redox reaction is taking place under acidic conditions. (You are, after all, either producing or consuming H+ ions.) There are slightly different rules for basic conditions: 1. Balance the reaction (using your method of choice) as if it were under acidic conditions. 2. Add one hydroxide ion per H+ ion to both sides of the reaction. 3. On the side with H+ and hydroxide, they become water. The other side simply gains hydroxide. 4. Be sure to check if you now have water on both sides of the reaction which could be cancelled.