Voter Turnout in the U.S._PE

advertisement

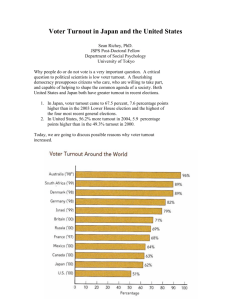

Florian Hernandez Professor William J. Greer Political Science 1100-041 30 July 2012 The Trend of Voter Turnout in the United States In the 2008 U.S. presidential election, voter turnout among the voting-age population (VAP) was tallied at 58.2 percent. (U.S. Census Bureau 3) The VAP is the U.S. population, aged 18 years or older. With only a little more than half of those able to vote showing up at the polls, the looming question is why this number is not larger. Voter turnout in the United States is less than desirable and has continued to decline for the past century. This has particularly been a concern in the last four decades, with numerous research, studies, and surveys being performed to arrive at a solution. No one answer has been absolute, but various methods, tactics, and strategies have been shown to improve or increase voter turnout. These approaches may not result in the same level of participation as other countries--some whose turnouts are 90% or better, especially those where voting is compulsory. However, the objective of increasing voter turnout is trumped by what is more important--the ability to engage citizens in the political process while maintaining the principles of democracy. To examine the issue of low voter turnout and the ways to remedy this situation, it is essential to review the record of voter participation, the history of voting and voting rights, the approaches used to improving turnout, and the actual effect on voter turnout. This writing will focus on voter turnout only for the years of presidential elections in the United States. And, for the purpose of maintaining consistency, voter turnout will be Hernandez 2 based on the voting-age population (VAP) rather than the voting-eligible population (VEP) as a longer history of data is available on turnout by VAP. VOTER PARTICIPATION RECORD Voter turnout in the U.S. was not always so abysmal. From 1840 to 1896, the turnout for the voting-age population (VAP) ranged from approximately 70 to over 81 percent. This rate was not sustained, however, as a significant shift occurred during the period 1900 to 1968, where the range decreased to 49-63 percent. Since 1972, we have seen a further decline of voter participation ranging between 49 and 58 percent. (Peters, Wooley) VOTING HISTORY This section reviews the evolution of voting, the right to vote, and legislation enacted to encourage voting. A number of Amendments and Acts have been passed to not only be more inclusive, expand the number of those able to vote, but most notably, to establish the rights of citizens to vote. In the Constitution, Article 1, Section 2 was modified by Amendment 14 to identify males 21 years of age or older to have the right to vote; it was ratified in 1868. In 1870, Amendment 15 was enacted to give AfricanAmericans the right to vote. Approximately 50 years later, in 1920, Amendment 19 was ratified to allow women the right to vote. In 1964, Amendment 24, Section 1, was passed, to outlaw the non-payment of a poll tax or other tax as reason for denying citizens the right to vote. The last modification to the Constitution was made in 1971 with Amendment 26 Section 1, a revision to Amendment 14, where the voting age was lowered from 21 years of age to 18 years or older. Hernandez 3 Despite these necessary changes, voter turnout did not spike following the enactment of these amendments. Other actions were implemented to help improve voter participation. This includes the passage of the National Registration Act, also known as the Motor Vehicle Law, in 1993. This law was to make it easier and more accessible for citizens to register and vote. States were required to make voter registration forms available in motor vehicle and social welfare offices. In addition, states had to allow mail-in registration to vote. Though this Act may have helped to increase voter registration, it still did not “budge” a rise in voter turnout. Other efforts to allow early voting and voting by absentee ballot also did not have a huge impact. (Hubert 121) APPROACHES to IMPROVING TURNOUT If significant changes to the Constitution, the laws, and other actions did not have a pronounced effect on voter turnout, what will? A great amount of research, surveys, and studies have been done to evaluate the many variables that affect voter turnout. This collection of data includes information on the: profile (white, college, educated, income, etc.); demographic (ethnicity, marital status, etc.); attitude (views of the government, politics, direction of the country); and psychology (how they see themselves as a citizen, perspective, social pressure) of voters. Campaign strategists have been keen on paying attention to the results of these studies. They use this information in mapping out specific groups who they can encourage and motivate to go to the polls in support of their candidate on Election Day. The success of utilizing this type of data was evident and highly effective for Barack Obama’s bid in the 2008 Presidential Election. Based on information collected by his campaign team, they were able to identify segments of the population that could be Hernandez 4 targeted and crucial to the vote count. This grassroots-organizing network then focused on battleground and swing states where these groups could be found. Many of these areas were typically low-income, Hispanic, and African-American communities. The 2008 election brought out 2 million first-time African-American voters; at least, 95% of black voters cast their ballot for Barack Obama. (Ramsey) Hispanics also made a big contribution to Mr. Obama winning the election. They helped to tip the balance in key swing states such as Florida, Nevada, and New Mexico. African-Americans did the same in the states of Ohio, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Virginia. (Frey) In addition, Mr. Obama’s campaign team hit college campuses where it incited and inspired students to be involved and participate in the political process. Overall turnout for young voters aged 18-24 saw the most significant increase in 2008, rising to 49% from 47% in 2004. (U.S. Census Bureau 5) The ability to mobilize and energize these voters was a success for Mr. Obama’s campaign. But, beyond all the hype and historical significance of the 2008 election, voter turnout in the aggregate (percentage of VAP) still did not experience the kind of increase that was anticipated. A report by Dr. Michael McDonald showed the VAP turnout rate rose a mere 1.5 percentage points in 2008 (56.9%) from 2004 (55.4%). (McDonald) It would appear that a solution to increasing voter turnout is elusive. However, the results of copious research, studies, and surveys done propose otherwise. Based on these findings, the factors affecting or prompting persons to vote, besides the mobilization of the electorate, were: positive incentives and reinforcement; direct/personal contact; social pressure; and compulsory mandates. Hernandez 5 As we saw in the 2008 presidential election, energizing and mobilizing segments of the population was effective. Another finding was that positive incentives such as holding an election celebration also encouraged voters. In an experiment performed in 2005 by Dr. Donald P. Green of Yale University (now at Columbia University), James M. Glaser of Tufts University, and Elizabeth M. Addonizio, a political science doctorate student at Yale, organized Election Day Poll parties in municipal elections in the states of New Hampshire and Connecticut. These parties were low-key, no “pomp and circumstance,” and held on the lawn of the polling place. Amenities consisted of small sandwiches, cotton candy and music. Working Assets, a company that supports progressive causes, also conducted similar events. The result was these festivities did increase turnout. In some areas, it rose by as much as 6.50 percent. (Drutman) Psychological approaches have also been tried to prompt individuals to vote. Carefully-worded surveys questioning people about voting and their intentions were found to be influential. For example, Todd Rogers, a Harvard professor and behavioral psychologist, conducted a randomized controlled trial in Pennsylvania where he broke potential voters into groups. One group received no calls, another group received calls with the standard get-out-to-vote questions, while the other group received calls asking planning questions, e.g., what they would be doing and where they would be coming from before voting. The outcome was surprising with the group asked about their “plan” to vote being twice as likely to vote. “There’s a lot of research showing that thinking through the actual moment when you will do something makes it more likely that the behavior will pop into your mind at the appropriate time,” explains Dr. Rogers. Asking Hernandez 6 the “planning” questions was like planting a seed of what actions the individual might take on Election Day. (Spiegel) Another survey by Christopher J. Bryan, Gregory M. Walton, Todd Rogers, and LCarol S. Dweck, also performed a survey, posing questions “invoking the self.” For one group, survey questions were phrased in such a way that placed the participant in a positive light should s/he vote. Another group was also asked questions, but phrased in a way that voting was considered more as a behavior than how it might identify them. The result was individuals in the group who were asked questions “invoking the self” had a greater likelihood of voting versus those who were asked questions about voting as a behavior. (Bryan, et al) IMPACT on VOTER TURNOUT Apparently, methods and strategies can be employed and successful in improving voter turnout. However, these techniques become less tenable in impacting voter turnout in the aggregate. This is primarily due to the dynamics of voter participation and the many factors that play a role. For example, a simple upward or downward movement in the variables used to calculate voter turnout, i.e., number of people able to vote and the voting-age population, will consequently alter this figure. The more salient element causing variability in voter turnout is human behavior. People can feel compelled to vote because of intrinsic interest, others due to their economic situation, and some who consider it a civic duty. Still, others may simply choose not to vote for whatever reason, even if they had dutifully done so in the past. All these factors impact voter turnout, is at the voter’s discretion, and is not controlled by government. Hernandez 7 Though increasing voter turnout remains a concern and a challenge, we cannot resort to controlling the rights of citizens. Countries like Australia, Belgium, and Argentina have compulsory or mandatory voting (by law); they achieve turnouts of nearly 90% or better. But as Maria Gratschew indicates, “compulsory voting is inconsistent with the freedom associated with democracy . . . . ” (106) Imposing this system in the United States may attain similar levels in voter turnout, but it is more likely that any proposal to enact such a mandate would be strongly rejected by the people. After all, enforcing such a ruling would not only be contradictory, but also defy the principles of democracy itself. Albeit, we don’t currently have a sure-fire solution to gaining voter turnout much above the 60% level, we do know that strategies and tactics exist that effectively reach and get voters to the polls. Inasmuch as we would like citizens to be more engaged in the political process, we are left to the nuances of individual behavior as we fortunately live in a free republic. Hernandez 8 Works Cited Bryan, Christopher J.; Dweck, Carol S.; Rogers, Todd; Walton, Gregory M. Motivating Voter Turnout by Invoking the Self. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 2 Aug 2011. Vol. 108. No. 31. 12653-12656. Print. Drutman, Lee. “Simple Ways to Increase Voter Turnout.” Pacific Standard. 31 Mar 2008. Web. 4 Jul 2012. Frey, William H. “Will 2012 Be the Last Hurrah for Whites?” National Journal. 13 Jun 2012. Web. 2 Jul 2012. Gratschew, Maria. “Compulsory Voting.” Web. 1 Jul 2012. http://www.idea.int/publications/vt/upload/Voter%20turnout.pdf Hubert, David. “Introduction to U.S. National Government and Politics.” 2008. McDonald, Michael P. 2012.”2008 General Election Turnout Rates.” United States Elections Project. Web. 3 Jul 2012. Peters, Gerhard, and Woolley, John. “Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections: 18282008.” The American Presidency Project. Web. 14 Jul 2012. Ramsey, Donovan X. “Obama Campaign Focuses on Black Vote, Target HBCUs.” The Grio. 23 Feb 2012. Web. 12 Jul 2012. Spiegel, Alix. “Can Science Plant Brain Seeds That Make You Vote?” NPR. 16 Jul 2012. Web. 17 Jul 2012. United States Census Bureau. "Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2008." census.gov. Jul 2012. Web. 10 Jul 2012. http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p20-562.pdf