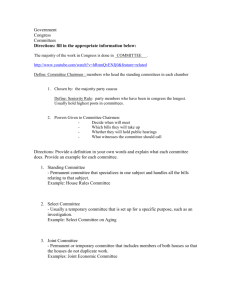

Unit 3 Review - Doral Academy Preparatory

advertisement